Paul Rabinow interviews Michel Foucault about his interview for the Herodotus[1]. In reply to Rabinow’s question about the political nature of architecture at the end of the 18th century, Foucault says that in the 18th century we start seeing political literature about techniques for governance in society where architecture and urbanism play an important role. Authors begin reflecting deeper on the social order, asking “What is a city?”, discussing the need to eradicate epidemics, prevent coups and promote family life (according to accepted morality of the 18th century), addressing representation of the collective, infrastructure and how to build houses.

Architecture has always been a tool in the hand of governors, priests and those who wish to demonstrate or communicate power. In the current search for an architecture that represents the period and free democratic regimes, it is important to examine not only the style, but the whole procedure and the relevance of local politics that outline the boundaries and planning conditions.

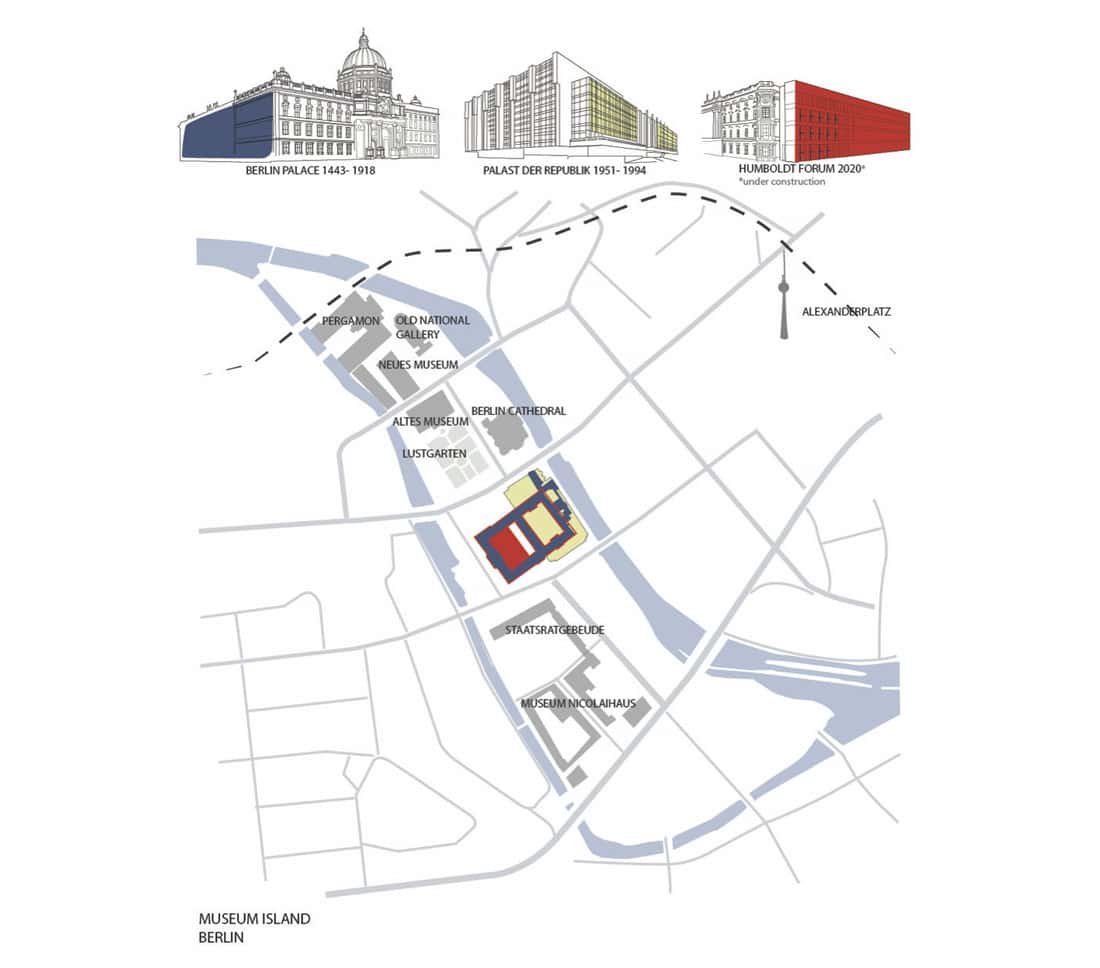

The Berlin Palace

The Stadtschloss, also known as the Berlin Palace, is the perfect example to start this paper with. It has it all: layers of historical conflicts and power demonstration through architecture. It tells the story of the city but also demonstrates a national identity conflict of the whole German nation. It expresses the evolution of private-civic initiatives in a strategic location that shapes the heart of the city, metaphorically and literally.

Since its completion in 1443, and until 1918, the Berlin Palace was the home of the monarchy and the Prussian center of power. During the Weimar Republic (1918-1933), the palace was used partly for state purposes but also as a public museum. In 1945 under the Nazi regime and during the Second World War, the building suffered severe damage. However, its structure and content remained sound and could be restored. In fact, the building was partly repaired and was used as an exhibition space. Although recent documents from 2016 reveal the intentions of the GDR to reconstruct the palace, it was ultimately demolished in 1950. The demolition took much effort and 19 tons of dynamite. Along with the decision to preserve the original balcony of the palace[2] and to attach it to the Council of State building, and to assign a new purpose to the empty plot as a parade area called Marx-Engels Square[3], it is the inevitable conclusion that the demolition of the palace was a political decision that sought to demonstrate governmental power.

In 1973, it was the GDR’s turn to build their own architectural power demonstration on the same plot: the Palast der Republik, which was mainly used for cultural purposes for the public. In 1990, the building was closed to the public due to asbestos contamination, and although the government made the effort to remove the asbestos, after the reunification they also decided to demolish the Palast der Republik altogether and put in a parking lot instead.

Considering its location and its role in the urban scenario, as well as the duration and high costs of the demolition (after going through the whole decontamination effort), the act of demolishing the Palast der Republik and turning it into a parking lot does not seem like an urban design decision based on spatial examination, but rather another demonstration of power sponsored by the government. Nothing demonstrates the superiority of the West and contempt for communist values more than demolishing its eastern symbol which occupied a central plot in the heart of the city. As if that were not enough, the decision to convert the plot into a parking area adds a ton of condescension and contempt. Here, the intention can be interpreted in two ways. One is to convey the message that the building was not good enough, and even a messy parking lot would be preferable so people can park their cars there until we have a better idea of what to do with the plot. The other is as a show of Western superiority: giving over the prime location to the symbol of progress (at the time), automobiles.

When restoring a building, one must decide on its most important era, analyzing the building’s role at that time, but the decision also involves what to restore and perpetuate and what you want to delete while shaping a narrative image for the future. “The story of the Stadtschloss encapsulates much of what has played out in Berlin over the past three decades – from charged debates about architectural aesthetics and practical questions about urban planning, to how a country deals with a troubled past and how it seeks to present itself to the world in the future.” [4]

At this point, though, that seems like history simply repeating itself. Unlike past decisions and actions, a new actor emerged and influenced the future architectural-urban declaration: private initiatives arising from the public.

When first completed in the mid-15th century, the palace was constructed to serve the royals, to serve their needs and to be built according to their vision. In the GDR, there was a shift, and the building was constructed by the government, for the government but also for the public. Today, the decision making was done with the public and for the public.

The latest evolution, which will take the form of the Humboldt Forum, began with an agricultural machinery salesman from northern Germany by the name of Wilhelm von Boddien. Von Boddien actively promoted the idea of reconstructing the Berlin Palace in its Prussian Baroque style. Von Boddien raised money and used his political connections for the benefit of the project and manged to transform the initiative into a national effort which resulted in reconstructing a building on the plot. The new building, called the Humboldt Forum, will be opened to the public in December 2020 and will consist of classical and modern elements. It will perform cultural functions that will try to represent the new German vision, as well as its historical complexity. The new building, designed by the architect Franco Stella is a politically correct, democratic building declaring that it just wants to keep everyone happy and bring an era of conflict to an end.

The Evolution of Decision Making

Saying that architecture is a reflection of its time may not always be accurate, simply because public buildings and urban plans take more time to execute than devising a law or replacing a government. Demolishing on the other end, can go faster. Both methods are used as political statements for the short term. However, in the long term they influence and shape the urban scenario and can change or preserve the cultural/social climate. The question that emerges is: Who should have a voice and who should lead the process? Is it the state, using legislation following a ‘one size fits all’ approach? Is it the public, represented by local citizens who do not always understand the broader context or have access to professional tools? What is the role of the planner? Is it really to keep all the parties involved satisfied?

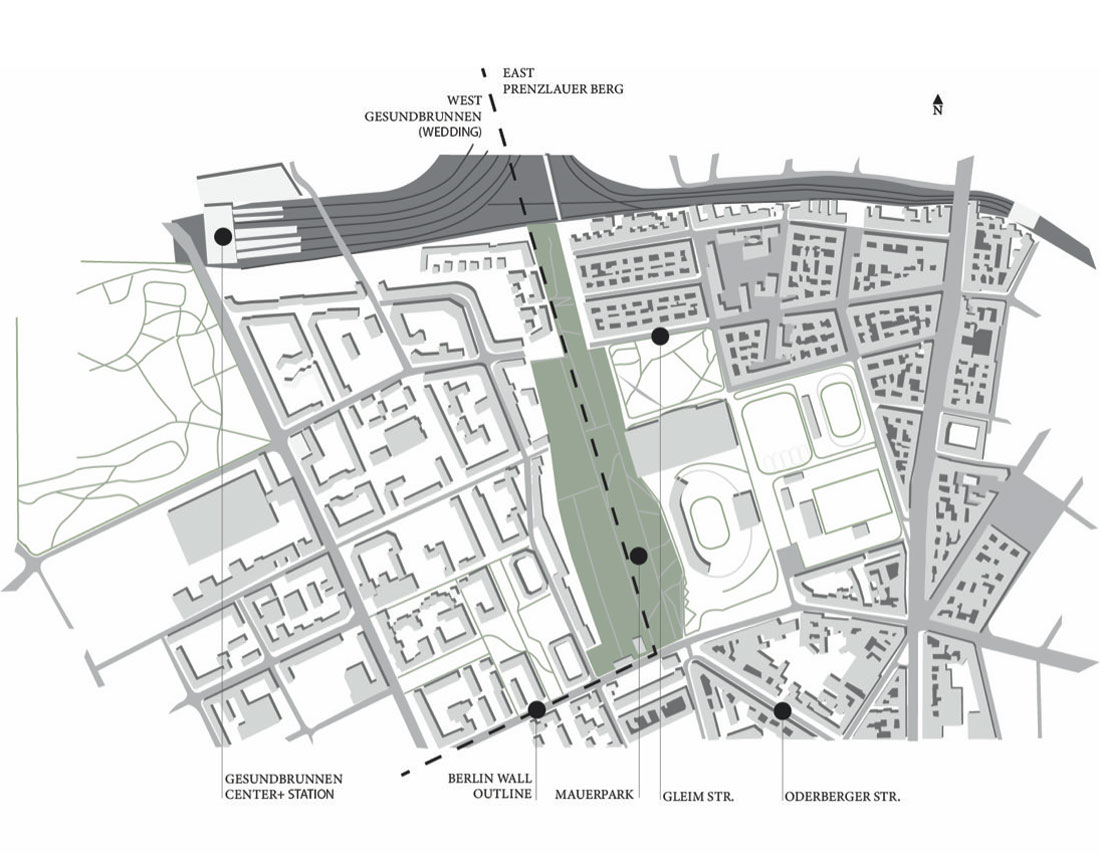

There are two case studies to relate to in this context. The first is the seam line between two neighborhoods in Berlin: Wedding (Gesundbrunnen) and Prenzlauer Berg. The seam itself is known as the Mauer Park. This case study shows the long- term implications of the Berlin wall and the role of the public in the decision-making process. The second case study is Curitiba, Brazil and the role of Jaime Lerner, an architect and urban planner, as the mayor. The second case study highlights the impact of having a professional urban planner as the urban

process leader.

An Urban Barrier: The Long-term Effects

The Berlin Wall was built in 1961 and was finally taken down in 1989. The 155-km wall was built by the GDR to prevent the migration of their citizens to the western part of Berlin and from there to the western part of Germany. There is nothing more political than a wall defining a border between two different political entities. However, whereas the wall was an immediate reaction to a temporary political state, its implications as an urban barrier are still evident today, years after the wall was taken down.

Today, our image of the Berlin Wall is of huge concrete blocks (3.6 meters high, 1.20 meters long) which were, in fact, only one layer of the barrier. There was also the “Death Strip”, a wide buffer zone associated with the fourth generation of the wall’s evolution. In some areas, the width of the Death Strip reached hundreds of meters. So, once the wall was taken down, in addition to the economic, social and cultural gaps between the west and east, there was a massive urban incision dividing the city, which also offered potential at the same time. The urban challenge was to heal the incision and characterize the scar in the urban fabric.

During the Second World War, about 80% of Berlin was destroyed, and about one-third of Berlin’s housing was uninhabitable.[5] With the division of the city into East and West (four quarters: American, British, French (later united as West), and Soviet(East)), each political entity had its own method of rebuilding its side of the city. In West Berlin (until the early 80s), to avoid perpetuating an acceptance of the city division, and with no urban master plan, the method was demolition and evacuation of the ruins to clear the way for new social, modern buildings with emphasis on green open spaces. In the East, they reconstructed the ruins with minimum investment and so kept the traditional typology of dense housing alongside wide boulevards for the party’s parades. So once the wall fell, there were not only two very different cultures but also different urban layouts and housing typologies on either side of the incision. Once the wall was gone, the discussions began regarding the nature of the reconstruction of the remaining urban scar. The discussion focused on the seam between East and West and dealt mainly with the debate over regulation and architectural artistic expression and less about how to bring the two culturally and socially divided sides of the broken city together.

Today, more than 20 years after the wall was taken down and with no clear master plan, it is still present. The scar tissue has perpetuated the incision. The situation may have changed, but the wall’s path is still a strong urban barrier. An interesting location is the area around the Mauer Park. Between two neighborhoods, Gesundbrunnen (Wedding) on the West side and Prenzlauer Berg on the East side, along the path of the former wall (Mauer in German) there is a wide park. The story of the park began after the deterioration of the wall and demonstrates a local civic initiative translated into an urban plan, as well as the importance of a street-level perspective that reveals what a broader master plan might miss.

At first, city planners suggested using the empty path as a highway ramp to connect the center of Berlin with the Berliner Ring, a main road surrounding the city.[6] Residents from the Gleim neighborhood and Odenberger street, both in Prenzlauer Berg on the East side (where the houses are built in a denser manner and have less open spaces) objected to the plan and pushed to convert the road into an urban park. Today, the Mauerpark is a green, creative island, a microcosm connecting the north part of Prenzlauer Berg with the city center via pedestrian paths, playgrounds and greenery, thanks to the residents of the neighborhood initiative Freunde des Mauerpark (Friends of the Mauer Park), an organization that “puts a special focus on the transparent involvement of citizens and a fair

balance of interests.”[7]

Although the Mauer park performs as an interesting seam, hosting a diverse population for a wide range of leisure activities, due to its size and the fact that it breaks up an urban sequence, it also perpetuates a cultural and socio-economic gap. On the one hand, there is Prenzlauer Berg, characterized by Wilhelmine buildings[8] that survived the Second World War and mixed-use streets that cater to a yuppie lifestyle. The neighborhood went through intense gentrification first attracting young, creative people looking for cheap and/or alternative housing. At the same time, foreign investors began purchasing the previously state-owned properties, renovating them and increasing their value, pushing the previous GDR tenants out. At a later stage, affluent people arrived from southern Germany, followed by immigrants from western European countries, maintaining a young age population with a high birth rate.

On the other hand, on the West side, there is Gesundbrunen (Wedding). Before the wall was built in 1961, the area between the Humboldt Park and what is now Gesundbrunnen-Center was a popular leisure street attracting many people from the East side due to its proximity to the East and its commercial offer.[9] Once the wall was constructed and the Gesundbrunnen area emptied of people, the whole neighborhood started to decline. In parallel, the German government signed an agreement with Turkey which resulted in a wave of migration: 825,383 people arriving mainly from the Turkish countryside. Looking for cheap housing, they found their new homes in Gesundbrunnen. From the mid-1950s to the early 70s, there were social government initiatives to develop new housing typologies and promote urban renewal. However, today, Wedding is one of the poorest neighborhoods in Berlin, with about 17% of the population supported by welfare, an unemployment rate of about 26%, and 27% of residents living below the poverty line.

The Mauer Park is a successful island in the city. However, it does not bridge the gap between the West and East. The park answered a need that arose on the East side, whereas the West needed an urban continuum, encouraging passage between the neighborhoods instead of urban boundaries. A border, even if it functions as a positive spatial element, is still a barrier. So, while the civic initiative has worked well, the broad and non-politically motivated planning leadership is absent and is needed to repair the long-term influence of a political decision made 60 years ago.

The Collective Dream

Time and political stability are needed in order to execute significant public projects. To execute innovative projects that require new ways of thinking and acting, the public must be involved in the task, as significant change requires a collective effort. “Politics is about providing a collective dream,” Lerner says, “and creating a scenario that everyone can understand and see is desirable. Then they will help you make it happen.”[10]

The architect and urban planner Jaime Lerner was acting mayor of Curitiba, Brazil three separate times, and he was the one to led the changes that transformed Curitiba into a model green city for the world. The challenges Lerner described[11] are political and bureaucratic obstacles alongside traditional public attitudes., Without social-political distinctions between neighborhoods or residents, Lerner planned a multi-layer transverse change rooted in the understanding that things are interdependent. It was a new vision for a new city lifestyle to prepare and push the city towards healthy and sustainable growth in the future. It seems like the discussion was already going on, but Lerner was the one to translate the long conversations into action, overcoming the mental barriers originating with outdated traditions and entrenched habits.

Lerner’s first project in 1972 earned him an early reputation as an enforcer. He proposed transforming the Rua Quinze de Novembro from an automobile thoroughfare into a pedestrian mall. “At first, the shopkeepers were furious with the mayor,” Rabinovitch says. “People had the habit of stopping their cars in front of the stores, buying what they wanted, and then getting back into their cars. But that meant that when the shops closed down the city center was dead….” “Every time, you always face a big resistance,” Lerner says. “When we first proposed the project, we tried to convince the merchants. We showed them designs, information […] It was a big discussion. Then we realized we had to have a demonstration effect.” So, Lerner took the plan to his director of public works, saying: “I need this [built] in 48 hours. […] He looked at me and asked, ‘Are you crazy? It will take at least four months.’ […] “If I’d received a juridical demand to stop the project, we would never have made it,” Lerner recalls. “So, we finished in 72 hours. […] In the end, one of the merchants who wrote the petition to stop the work told me, ‘Keep this petition as a souvenir, because now we want the whole street, the whole sector pedestrianized!’”[12]

Lerner’s philosophy of taking action immediately and adjusting later had proved itself, since it assumed that changes would follow since the future is not really predictable. The plan to act now left room for adjustments; but once you get to the point of making adjustments, you already have the collaboration of the public. In the discussion democratic architecture and urban planning, Lerner had a different approach from the one implemented on the Berliner Palace plot (the Forum). He didn’t try to make everyone happy all the time. Nonetheless, he managed – based on his wide perspective and strong drive to action – to take a collective vision and push it past the political obstacles into realization in short time.

Democratic Urban Planning

Now, Lerner’s architectural and urban planning office is taking action on the political front and is educating candidates, before they are elected to office, on how to make sure that prior urban decisions and actions will have continuity once they are elected.[13] This effort, while it has a clear political agenda, is an innovative step toward acknowledging the value of well-thought-out sustainable urban planning and its long-term benefits for both culture and nature.

Architecture is the art of creation; politics is the art debate. The two have had a strong connection in human history with an unequal relation of subordination, in which the politics dominates the planning. The search for democratic planning is ongoing. Democratic architecture or urban planning is not necessarily a search for a new aesthetics or style; rather, it affects the method of creation and decision-making processes. Perhaps the utopic concept, radical as it is, would be to separate the urban planning from government by establishing a separate and independent democratic establishment. That would free the public from political subtexts, allowing urban planning (led by professionals and including the public) to take significant steps and improve cities in order to better accommodate the people and be kinder to the planet that hosts us.