In the last two decades, much effort has been made in our cities to make them more desirable with the aim of introducing mixed uses. The city centers are protected and preserved for their historical value and their importance in collective memory. At the same time, a lot of care and protection is also given to residential areas in order to meet the demands created by an ever-increasing number of residents. In a totally different approach, we are left with industrial areas continuing to be developed according to autonomous policy rooted in private ownership, mainly driven by economic priorities. The lack of rules and long-term strategies make these areas a realm of highly profitable independent interventions, regardless of their impact on residents’ wellbeing and the potential for new forms of diverse neighborhoods. The result is a process lacking urban integration and missing opportunities. To reverse this tendency, we need to cease considering centrally located employment land (be it infrastructures related to industry, transportation or logistics) as at odds with residential neighborhoods.

There is an intense competition for space in our cities. Among all the sectors automatically integrated (from housing to offices to retail), industry is usually left out of the reallocation process. This sector is almost never considered as a major actor in our city centers, and therefore it is hardly ever integrated into the planning projections. This prevents the full spectrum of urban figures from coming together harmonically and excludes the potential of those employment lands from the desired mixed-use ideal. This is due to a lack of growth policy specifically addressing a valuable future for employment land. The lack of interest in dealing with industrial areas is reflected in the government’s unilateral idea of industry. The general consideration focuses on oversized dimensions and monofunctional typologies, orienting their reading towards characteristics that are incompatible with everyday life (such as noise, pollution and typological autonomy).

For this reason, on the one hand, we very often encounter developments of employment land that adhere to a blind logic, leading to unsatisfactory results. On the other hand, it has become a regular occurrence for industrial areas to be pushed to the periphery or exclusively designated for non-specific housing developments. What remains within the urban fabric is a homogeneous repeating condition and a missed opportunity. If we aim to create a wider framework for such conditions, it is worth looking specifically at the case of a broken fabric.

Site of Study: A Broken Fabric

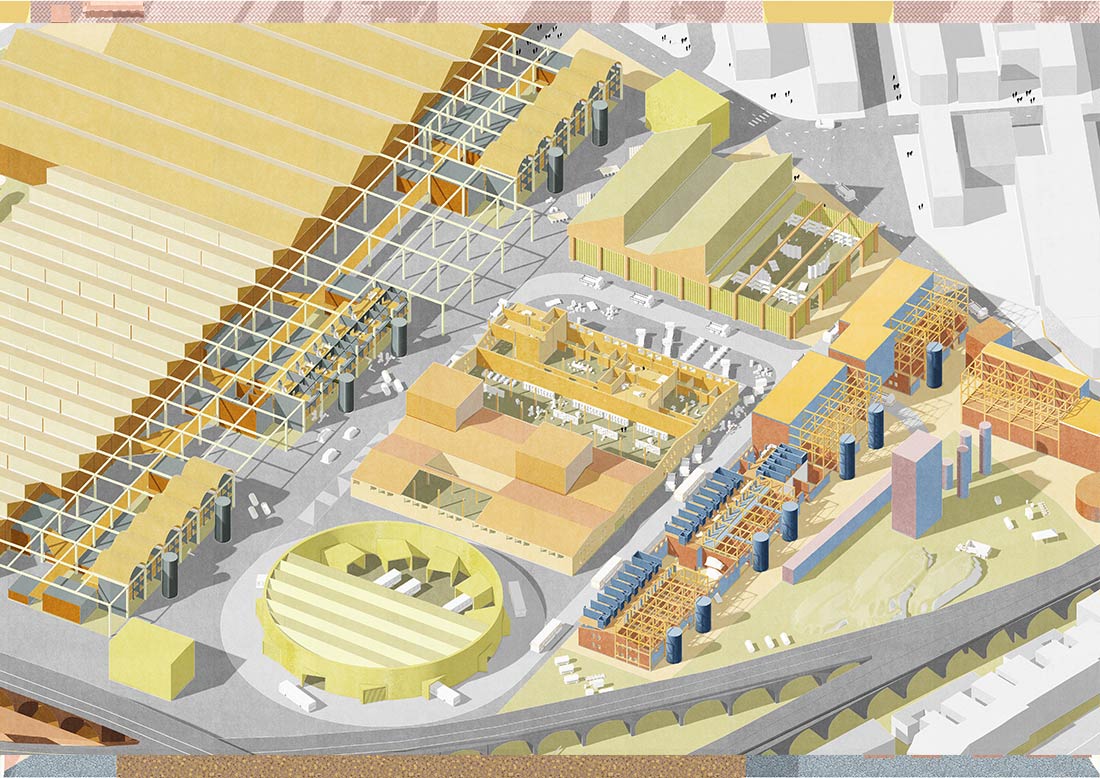

In order to demonstrate this notion, we examined the Silverthorne Road industrial quarter, a centrally located industrial working estate situated between Battersea Park and Clapham Common in the City of London. Based on this design-led project, focused on a heavy working industrial area, we will learn from the hidden opportunities generated from its industrial elements and irregular typologies. The morphology is designated for industrial purposes, formed by railway connections, functional outdoor surfaces and large-scale buildings, oriented in keeping with an autonomous logic toward the inside of its area.

Compared to the regular and street-based adjacent housing fabric, the industrial area (with a size of 7 ha), appears as a disruption and complete disorder. The irregularities emerge in different scales and languages. We find big buildings and small buildings, all inconsistent in their orientation. The variations continue in the outdoor surfaces, which appear vacant and simply random in their purpose.

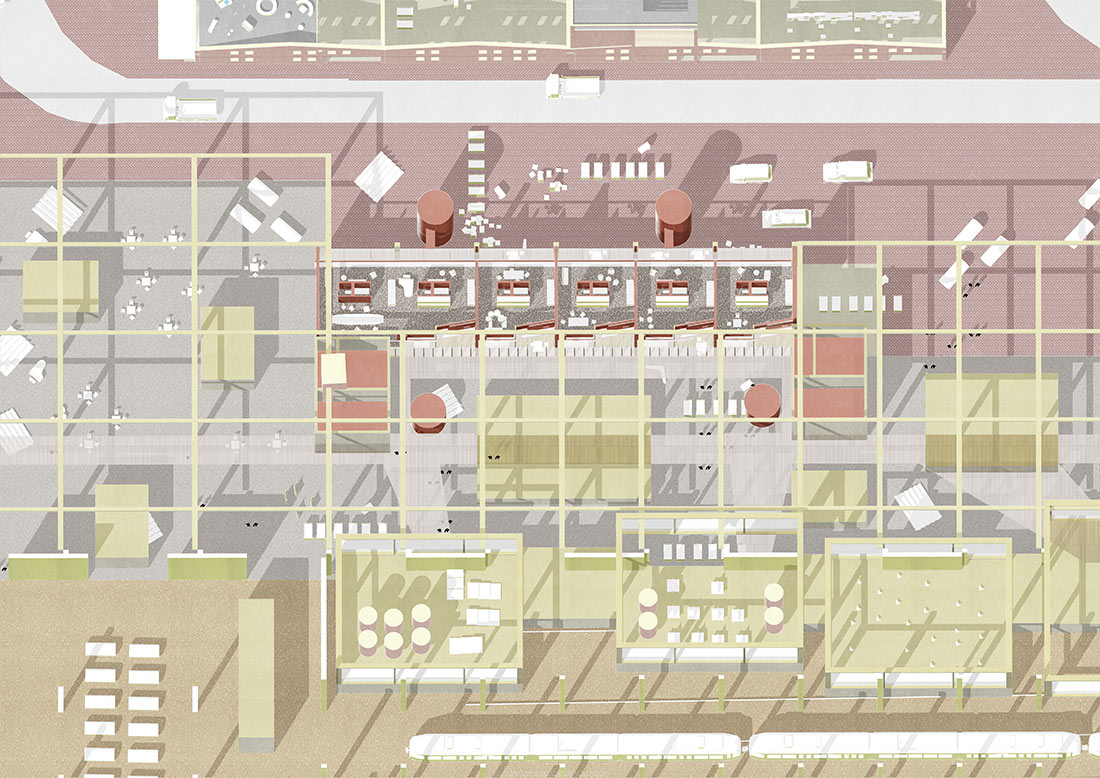

However, by looking closer at its hidden hierarchies, we recognize a certain consistency of variations, and an order in itself. The industrial area is strongly formed by transport vectors and access lines. The large buildings are oriented along connecting side streets serving the areas, for large transport vehicles such as trucks and vans. The middle-sized buildings are oriented according to the railways. The smallest of the buildings surround the outdoor surfaces for logistical support and storage.

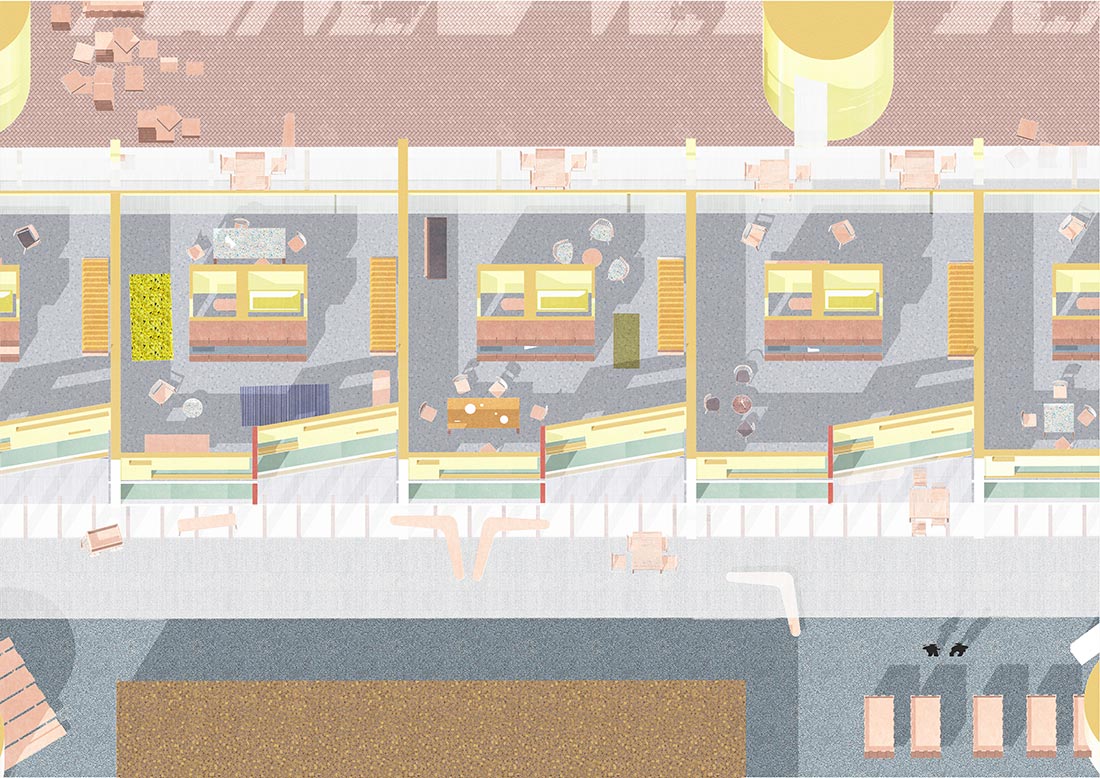

On the one hand, part of the buildings here conform to a low-rise shed typology (mostly horizontal, large-scale, rectangular, with a lightweight metallic roof and direct ground-level access); on the other hand we find uncovered large parking fields to park or maneuver transport vehicles. Because we do not often have the opportunity to look at vast open spaces within a dense city, we should now change perspective and start appreciating what the existing structures may offer us: big footprints in the middle of the city; a resilient typology that anticipates future inhabitation and changes over time.

Considering the possibilities for collective governance of employment land, we find fuzzy plot dimensions based on the historical process of ownership. Their size, number and orientation may have changed over time while changing ownerships. While this shows a muddled organization, we could envision in these irregular and vast plots a greater opportunity towards a desirable framework of collective plot regulation, which would allow a greater number of individuals to become part of the decision-making process. This can offer a strong counterargument against master plans as fixed, non- process-oriented instruments that lose the strong flexibility of a shared adaptability.

Common Strategies

To understand the existing answer to similar sites through case studies, we could start by having a look at the Greenwich Peninsula Design District. The project shows how developers usually tend not to preserve the essential industrial uses of the former industrial sites they are taking over. The result is a limited promise, seized upon as a nostalgic dream, thereby unconsciously transformed into an unsatisfying theme park. In this sense, it excludes a wider range of possibilities through its opportunistic consumerism. The identity of the place is lost, and with it, its crucial involvement in the neighborhood. In order to seriously think about a place for the creative industries and their new generations, we should once again move away from a homogeneous, rigid master plan that only leads to an illusionary space that misses the given opportunities of industrial estates.

Further case studies including the Morden Wharf, or the old Vinyl Factory, once more demonstrate the consequences of the lack of existing policies within the urban framework. Their failures, or short-term successes, emphasize why it is now important to call upon government interest, and also the attention of developers and stakeholders, to tackle a recurring problem: the co-location of housing within employment land and a longer-term strategy for operating with irregular urban conditions. Therefore, we need to start with a new formulation of an alternative approach to employment land and a new attitude towards the means of production.

Vision and Scope

In contrast to the previous common strategies, we will try to understand the potential of a specific society, holding the role of a middleman, in handling those very irregular urban elements. They are capable of interacting and dealing with the broken fabric, transforming its offers into opportunities for a new meaningful neighborhood.

This new group of actors is called the Makers Society. The Makers Society consists of people from a specific society who are capable of interacting with production, who like to share facilities in order to perform an artisanal or industrial practice. At the same time, they enjoy a working environment that has domestic characteristics. Today, these specific concerns, shared by a growing number of people, can easily become drivers of change that offer an important bridge for living differently in an area marked by heavy industry.

The Makers Society has the ability to inhabit irregular typologies by transforming buildings into new working spaces and creating a collectively driven work environment. The shift of perspective that this society offers gives us the chance to adopt a new lifestyle, now able to embrace and use irregular spaces. This triggers a strategy built on what is there, to use and harness it over time.

Do they have the potential to meaningfully preserve important pieces of urban diversity in our cities? What if their attitude allows us to maintain the urban fabric of these irregularities, the atypical geography and its specific mobility? What if they could even keep the production activities running?

What if the industrial areas’ real potential lies exactly in its own consistent logic of typological variations which, when colliding, could offer a significant contribution to residential aspects?

The following project explores a design-led process, based on typological upgrade strategies, that both optimizes a functioning industrial area (by retaining 80% of the existing industrial activities within their buildings) and intensifies it with smaller forms of production (the Makers’ workspaces) and alternative forms of housing (living differently) by proceeding with a typological transformation.

This thesis operates within an existing centrally located employment land of 7 ha. It consists of heavy industrial activities – train maintenance facilities and a depot, a bus depot and several other logistics features – and will be scaled up within five typical industrial typologies. The additional program consists of a variety of makers’ production activities such as workshops and creative offices, additional facilities for everyday life (educational and recreational), housing in the forms of collective living for students and duplex housing that combines housing and working. All tested buildings are undergoing a type of challenge and reaching desirable transformations for living and working differently within an industrial area.

As an alternative to a masterplan, this project relies on a step-by-step process over time, evolving into a framework that actively invites actors to use and reuse, develop further, and redefine the change of process towards manageable stages. To make this strategy succeed, it relies on the Makers Society involvement. Thus, they play a crucial part in interlinking housing and industrial activities towards sustainable development to transform an irregular urban fragment into an inclusive neighborhood within a relatively easy walkable distance, which we shall call the Makers-Scape.

The Makers-Scape is divided into different building typologies with regard to the various requirements for the individual premises. In this way, robust structures such as hall buildings can be created in a conglomerate or separated. Uninsulated rooms or rooms with a lower operating temperature are placed in a gradual separation from smaller rooms that have a higher standard of construction and higher requirements for thermal insulation and sound separation. We might create interface climates and sound conditions. Furthermore, robust structures can be adapted to the requirements of future uses.

In addition, we might apply a reinterpretation of irregular plot dimensions towards a new understanding of sharing. Equally, we might find an opportunity to transform a former access road into an interior production corridor, with new forms of mobility that enable industrial areas to become accessible to the neighborhood.

In order to get a deeper understanding of the notions introduced here and their potential consequences on the design of our major cities, this thesis is articulated in three chapters. After a first chapter focusing our interest on the potential implementation of daily life into the broken fabric, we will articulate a second chapter on the aesthetics and design implication of such cohabitation. The third chapter aims to understand the logic behind a prospective strategy to break up the typological irregularities into definable strengths for inhabiting cities.

The argument is nourished throughout by the research and thoughts generated from a design-led project around a vision of new forms of production with integrated housing.

Conclusion

I believe industries belong to the fabric of the city. They not only provide diversity in our economy, but also desirable heterogeneity through their physical impact within our urban network. Industries appear in various forms of employment and everyday services, such as manufacturing, distribution, storage, utilities, urban services and creative production. Even the less well-known industries are in fact essential to our daily needs, and thus, they are a crucial substructural element to our quality of life. And yet we very often consider working industrial areas as backyards or even junkyards, and unfortunately believe that their persistence within our cities might hinder the progression to a desirable urban future.

When considering a valuable future for centrally located employment land, we often lack policies, systematics and long-term strategies that could lead us to operate with their particular conditions in a beneficial way. In our cities today, we are facing an intense pressure for densification. Whereas it is now unavoidable to start to mix and combine different functionalities, employment land is very often left out of the reallocation process.

The gap between the different characteristics of housing and heavy industries, traditionally considered incompatible, is deemed to hinder any vision towards an inclusive neighborhood that allows a profitable cohabitation. Indeed, if we look at case studies that have already dealt with this problem, we often see developments built according to a blind logic, mostly driven by economic priorities and without preserving the essential industrial elements.

Nevertheless, this thesis has shown that the existing urban irregularities have great potential and could offer a more sustainable way of densifying our cities. The challenge lies in dealing with complex characteristics, but they can actually appear as facilitating conditions for new forms of collaborative management of a shared ground by a variety of actors. To imagine and set up this necessary framework, we need to accept a shift in our expectations and set aside our prejudice. Through a series of incremental strategies to implement accurate designs, we can reach a real desirable typological upgrading for industrial buildings and their surroundings.

This new approach is centered on an underestimated, yet meaningful social paradigm and posits the Makers Society as a crucial driver of change – society that is capable of acting as a middleman between heavy industrial characteristics and domestic demands. The achievements occur in the emergence of a new neighborhood, the so called Makers-Scape, which opens a formerly isolated industrial area towards its adjacent environment and creates new spaces for employment, shared facilities and accommodation for living and working differently.

This Makers-Scape enables us to keep these urban irregularities in forms. By acknowledging the urban irregularities, the Makers-Scape can maintain the use of its production activities, valuing the specificities of the urban fabric, geography and mobility – a set of characteristics the Makers interact with on a daily basis.

The Makers are able to constantly activate them through respectful transformations, managing to preserve an important piece of urban diversity in our cities – a diversity that fosters a consistent logic of adaptation through time, revealing the real potential of these urban figures. Finally, in order to achieve a sustainable strategy for dealing with employment land, we might question traditional governance of zoning. Indeed, the regular idea of zones remains an obstacle that limits any further intensification as soon as we consider urban regeneration on the larger scale represented by the Makers-Scape.

Thinking prospectively, we could look at an urban section of a wider scale with all the previous notions in mind, in order to enlarge the scope of the discussion. We could aim to think collectively by identifying similar repeating conditions across the city in order to redesign a sequence of upgraded broken fabrics, creating a city-scale network of epicenters that can breathe life into the city and generate sustainable new dynamics.