This chapter considers drivers of island city land reclamation as well as land reclamation’s impact on public space. It represents a reworking of material previously published in Grydehøj. [1]

Theorising Between Land And Sea

Over the past few years, researchers have increasingly drawn attention to the importance of land-sea relationships in social and political processes. Such perspectives have emphasized how these processes are simultaneously fluid and crucial for understanding the human and non-human environment (e.g. [2][3] Peters, 2015). [4][5] In the case of islands and archipelagos, the coproduction of land and sea is enhanced, and the urban/island whole is narrated, negotiated, and experienced on its edges.

Such theoretical approaches may be particularly relevant when considering the politics of transformation from water to land. Reclamation, the most commonly used English-language term for the construction of ground where water once had been, is in a sense inappropriate; land reclamation does not typically ‘reclaim’ lost ground at all but instead extends solid ground into new frontiers. Marine spaces often provided the initial rationale for founding human settlements in coastal zones. As a result, terrestrialisation projects – which inevitably alter the nature of adjacent marine spaces, ecosystems, and ‘un-reclaimed’ shorelines as well as drive subsequent adaptation processes – are far from straightforward triumphs of material fixity.

Land Reclamation In Island Cities

Islands are strongly associated with urbanisation: a mix of territorial, defence, and trade benefits have historically made small islands ideal sites for seats of government, military, or economic power. [6] Because many islands have been connected to the mainland through reclamation, we often fail to recognise island cities for what they are. [7] Examples of former islands abound, including Dubrovnik, Manila, Mexico City, and Tyre. Yet there are still many major island cities that have expanded significantly through reclamation but around which the waters have not completely receded, such as Abidjan, Amsterdam, Lagos, Mumbai, St Petersburg, Singapore, and Stockholm.

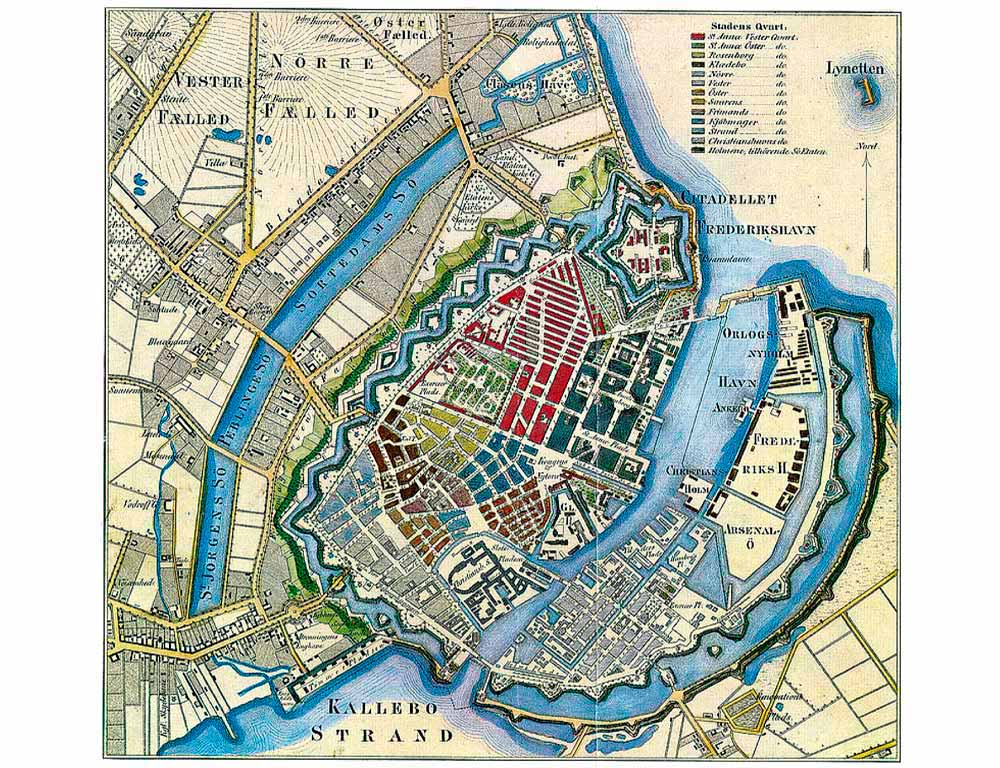

Figure 1: Map of Copenhagen, mid-19th Century.

The things that people do with coastlines change, and economic circumstances may argue for the creation of new coastlines to serve new uses, for new users. The Copenhagen archipelago presents an instructive case. Copenhagen’s castle island, Slotsholmen, is now nestled in the city centre but was once located considerably offshore. Slotsholmen’s 12th Century re-engineering and fortification were performed in the service of the city’s dominant political force: the island both protected the harbour from incursion and provided a seat from which political power was projected into the city. Changing politics and economies, however, meant that a distant castle island was no longer the ideal seat of power. New phases of urban development privileged the city’s commercial, industrial, and administrative functions. In the 1600s-1700s, reclamation projects saw the city rush out to meet Slotsholmen from the west and encapsulate it in a crescent of artificial islands to the east.

Figure 2:New artificial islands have been created alongside older reclaimed land as Copenhagen’s Sydhavn neighbourhood transforms from an industrial to a residential zone.

Over the centuries, Copenhagen’s growth continued. Capitalist urbanism grants value to empty coastlines; yesterday’s coasts hold less value than tomorrow’s. As a result, new waterfront property is manufactured in front of old waterfront property.

Since property values are frequently highest near the city centre, maritime industries are pushed ever farther from the urban core, [8] sometimes occasioning successive waves of reclamation and renewal. The seeping away of industry from Copenhagen’s reclaimed Sydhavn district in the 1990s opened the area to residential and business development in the 2000s, resulting in ever-expanding Amsterdam-style archipelagos of artificial islands separated by canals. Once developers have reaped the profits from selling residences with an attractive view, they are incentivised to create even more property, regardless of how this affects users and residents of the existing new coastline. Low-value industrial actors, meanwhile, are kept constantly on the move: In the mid-1990s, industrial redevelopment pushed the old fishing harbour in the inner Nordhavn district out to the extremity of this artificial peninsula. Nevertheless, grand plans for Nordhavn as a new business, residential, and industrial centre will are seeing the fishing harbour displaced yet again. As the existing Nordhavn is being filled, the peninsula is also being expanded by a third (1 km2) using earth excavated for the new Metro rail line. Subterranean rail transport thus literally provides the grounds for new high-value business, residential, and industrial life: Major infrastructural projects can be mutually justifying, requiring ever-more extensive urban interventions.

Island cities have led the way in these processes. New York City accrued complete new shorelines during its 18th and 19th Century booms and ultimately lost its marine orientation. [9] Manhattan’s experience has recently been mirrored on the Chinese island of Xiamen, the land area of which has grown alongside its surging port and manufacturing economy. An important port city since the mid-16th Century, Xiamen’s population has recently exploded, rising from 639,000 in 1990 to 2,207,000 in 2010. [10] Over the past two decades, reclamation has simplified the island’s coastline into a more perfectly circular shap. Xiamen’s turn away from the sea is strikingly exemplified by the case of Yundang Lake: this former harbour (10 km2) was enclosed by a sea wall and reclamation, transforming the bay into a heavily polluted lake system. In 1988, the government initiated an expensive “integrated treatment project” aimed at Yundang’s “restoration” and “rehabilitation.” The project has transformed the lake into an urban leisure, business, and tourism zone (1.7 km2), [11] turning it into Xiamen’s “money magnet,” a site of intensive gentrification. [12]

At a larger scale, nearly 250 km2 of Tokyo have been constructed through an ambitious series of drainage and reclamation projects, primarily since the 1950s. Even ancient Tokyo (formerly ‘Edo’, i.e. estuary) had been subject to politically motivated wetland reclamation activities, and the city’s historic core was composed of numerous interconnected islands. In the 1960s and 1970s, the Japanese government supported – sometimes in the absence of compelling demand – the construction of industrially focused yet mixed-use islands offshore Tokyo, Osaka, and Kobe.

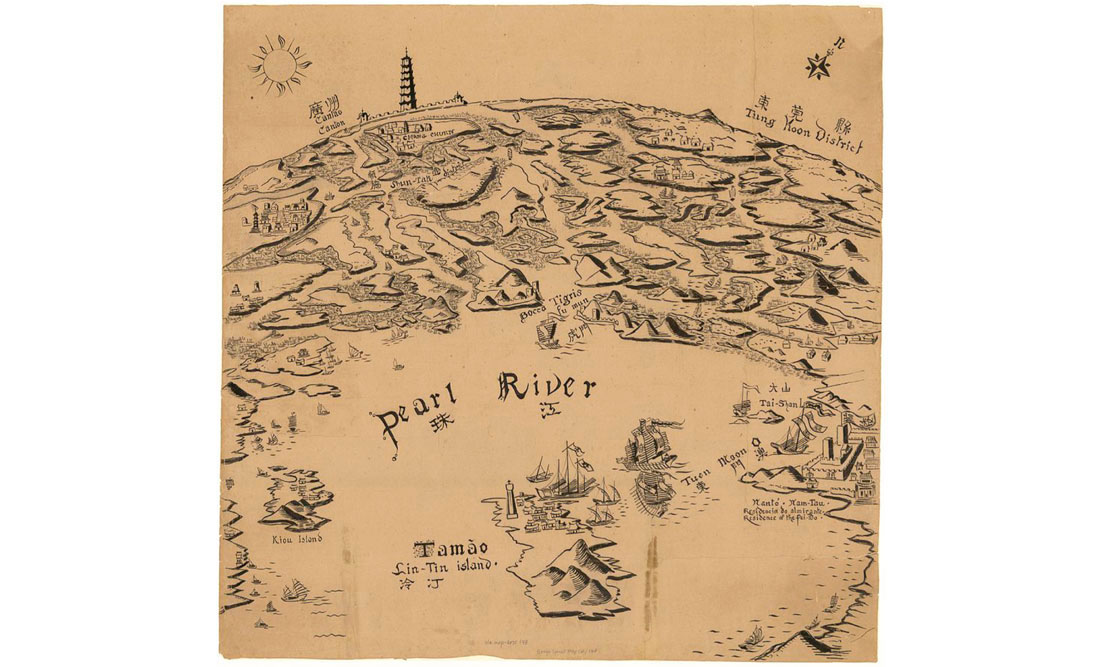

Figure 3: ‘Entrance to the Pearl River, on the Way to Canton’ by Baron von Reichenau, 1940

Figure 3: ‘Entrance to the Pearl River, on the Way to Canton’ by Baron von Reichenau, 1940

The world hub for land reclamation is, however, China’s Pearl River Delta. The ancient island port city of Guangzhou encouraged the urbanisation and expansion of numerous islands farther downstream in the delta. Although no longer popularly associated with islands, the Pearl River Delta’s archipelagic nature was evident to observers well into the 20th Century (Figure 3). In 1557, the island of Macau (and later the islands of Coloane and Taipa) came under Portuguese control, only returning to China as a Special Administrative Region in 1999. The Portuguese expanded their territory through reclamation, which has increased Macau’s land area from 10.28 km2 in the late-19th Century to 15.5 km2 in 1984 to 31.3 km2 today. [13] With a population of around 631,000, Macau is the most densely populated territory in the world. It is also the world’s most profitable gambling destination, with casino tourism centred on the so-called Cotai Strip of reclaimed land connecting Coloane and Taipa. [14] Macau’s form and function have developed side by side, with changes in the city-state’s economy and industrial composition prompting changes to its urban fabric. [15][16] The tightly clustered residences, temples, and small businesses of old Macau (much of it itself reclaimed centuries ago) contrast markedly with the towering casinos and purpose-built leisure districts that have risen up on Macau’s newer land. Remarkably, even in this tiniest of territories, Macau’s newest land is only problematically accessible by foot, intentionally cut off from old Macau by transport infrastructure designed for the taxi and tourist coach. Infrastructural efforts are made to shield tourists from distraction from lucrative gambling and high-end shopping expenditure (with the grudging addition of spatially limited value-added heritage tourism zones). In Hong Kong, on the opposite side of the Pearl River Delta, density imposed by island spatiality likewise incentivises reclamation. The location of the original British settlement was selected in 1841 due to its suitability for reclamation. [17]

Some artificial island ground – such as industrial zones – is hardly open to the public at all. In other cases, however, as with the residential islands of Copenhagen and the leisure areas around Xiamen’s Yundang Lake, residents and users of artificial island spaces buy into an illusion of public space. This is an illusion precisely because the use and prospects of these spaces are conditional upon the desires of the state and corporate actors that enabled and undertook the creation of the space.

Land reclamation is today popularly associated with the manufacturing of island paradises by property developers. The artificial islands of Miami Beach date back to the early 1900s, yet reclamation destined for high-end residences has entered a new phase in the past few decades. Such reclamation is perhaps most striking in Dubai. Despite the region’s considerable land availability, there has been a rush to engineer a series of artificial islands (including the Palm Islands, the World, the Universe, and the Waterfront projects) designed to maximise both real estate value and iconic impact from the serenely distant gaze of Google Earth. [18]

Dubai is not alone in its obsession with urban “gigantism.” [19] Around the globe, iconic skyscrapers and iconic artificial islands are presented as hallmarks of ‘world city’ status yet are simultaneously associated with privatism, exclusion, and hyper-inequality. Indeed, in the most comprehensively designed of such secessionary networked spaces, [20] manufactured islands and monumental towers often coincide, such as at Dubai’s Burj Al Arab and Atlantis hotels, the casinos of Macau’s Cotai, and Singapore’s Marina Bay. The combination of reclaimed land and monumental architecture is partly practical, for island-conditioned urban densification is a driver of both land reclamation and vertical urbanism. Despite attempts at universal iconicism, most such island paradises have been designed as residential or holiday enclaves and are grounded in a deeply troubling social exclusivity: wealth is the determinant of admittance, services are provided by immigrant labourers, and everything maintains the separation and segregation of welcome from unwelcome guests. [21]

Unlike Dubai, the Bahrain archipelago does not even lack coastline per se, but this Gulf island state has acquired around 70 km2 of new ground, the vast majority since 1965 and most in the past decade and a half. Such construction is rooted in a desire not only to proliferate valuable land with sea views but to do so in already densely built-up areas. [22] The ideal island is simultaneously an oasis of exclusivity and well-placed for deriving urban proximity benefits. That is, even when (potentially egalitarian) sprawl is possible, extraordinarily expensive and socially suspect processes of reclamation may be preferred precisely because there is more profit to be made in exclusivity than in inclusivity. Bahrain possesses a Dubai-style fantasy land, Durrat Al Bahrain, yet more significantly, its northern cities have extended tentacles out into the Gulf. The public has been displaced as Bahrain’s ancient fishing and agricultural industries have ceded terrain, both old and new, to the seafront real-estate market. Despite the immense expansion of its shoreline, only 3%-8% of Bahrain’s coast is publicly accessible. [23]

Figure 4: The dense urban fabric of Hong Kong Island is the result of large-scale land reclamation.

Capturing Unclaimed Space

Carmona [24] notes that there is nothing new in the idea that public space is precarious. I attempt here to reflect value upon public space by considering its antithesis: space that was never public, that is private by design. The fact that public space activism is particularly visible as a reaction to ‘urban renewal’ initiatives (where there is concern that corporate and state actors are seeking to enclose previously public space) should make us wary of instances in which these same powerful actors are able to capture space without raising the hackles of defenders of public access and ownership.

In highly dense cities in which spatial scope is exceptionally constrained (such as island cities), we might expect contestation over land to be exceptionally heated. The values of both public and private space will increase relative to their overall availability. The openness or publicness of such contestation is vital to the just development of the city. It is when conflicts over resources are not resolved but simply submerged and when spatial privilege becomes a fait accompli that urban society is prevented not merely from progressing but also from striving toward progress.

Reclamation has become a favoured strategy for coastal and island city development in part because it is a means by which elite actors can create new urban spaces while bypassing many of the tensions and contestations that result from attempting to claim a portion of the existing urban space for new purposes. Since reclaimed land quite concretely represents a blank slate for development, it could be deemed immune from claims of publicness. Yet such an analysis is not politically neutral: to deem reclaimed land a solid blank slate is to deny its previous fluid spatiality.

There is a tension inherent in how island spatiality prompts both urbanisation and land scarcity, resulting in extreme urban densification. These processes are compounded as agglomeration economies favour the spatially dense networks of industry, infrastructure, and knowledge that tend to arise in island cities in particular. [25] This increases land value and hence the demand for manufacturing ground where water once had been. Reclamation can thus seem to be an inevitability; As island cities grow in population and economic and political importance, they grow out into the water too. Insofar as the city remains substantially restricted to the island or the archipelago, land scarcity mitigates against sprawl, favouring instead piecemeal accretions to the existing urban fabric or the decisive establishment of dense satellite cities on nearby land masses.

Reclamation processes reflect reigning power structures and competing societal interests. Island cities may by nature demand land, yet demand itself is not enough: new ground cannot be created in the absence of pre-existing economic resources or a supply of labour capable of producing it. New ground thus tends to reflect the motivations of dominant societal forces. Thus, for example, we have seen Bahrain’s artisanal fishing cultures destroyed by needless reclamation (where sprawl would have sufficed). We have seen Copenhagen surrender to the vicious logic of technological successionism, with each reclamation project necessitating the next. We have seen corporate and state interests first enclose and ruin and then claim and financialise the waters of Xiamen.

Given the time-consuming and expensive nature of the reclamation process, the amount of new urban space produced at any one time is relatively small. Cumulative and successive reclamation of small pieces of land along the coast often disrupts the urban fabric since existing infrastructures (transport arteries, sewers, schools) were not designed with the reclaimed land in mind – hence the inefficient networks of parallel and disjointed roadways in Hong Kong and Macau, [26][27] the lag between residential island construction and services provision in Copenhagen’s Sydhavn, and the unintegrated drainage systems beneath Belize City.[28] Moreover, the construction of new urban space affects life in old urban space: the manufacture of new waterfront property can capture the coastline for elite interests, dispossessing existing users. Even when the public is not physically denied access, there may be “symbolic” impediments to waterfront access alongside such elite developments. [29]

Reclaimed land is by definition not public space, even if it happens to be state owned. Within our reigning societal conceptualisations of territory and ownership, the public lacks moral or historical grounds on which to stake a claim. Land reclaimed within the past decades has been capitalised since conception. It has never been public. This represents a wicked twist on Harvey’s “accumulation by dispossession.”[30] A city’s coastal waters may not be widely used for civic purposes and are thus difficult to define as public space, yet inasmuch as they are not a form of private space, they may be the next best thing: space that might one day be public. Urban sea space is a space within which future cities – perhaps more egalitarian, more open, more free – may emerge. Whenever such space is claimed by the interests of enclosure, it is a qualitative and relative loss for advocates of a more public city. Although the corporate creation of new urban space for development may be superficially superior to the violent ‘renewal’ of existing urban space, it also involves a dangerous avoidance of conflict: Locally controversial urban renewal projects sow seeds for protest, for activist involvement, for the emergence of democratising social movements. In comparison, the terrestrialisation of marine space disenfranchises and makes ambiguous non-elite stakeholders. By the time this space ceases to be liquid and has solidified into territory, it is too late for contestation. The land-sea interface is at once the most profound urban space and that which is least defended by arguments of publicness.

Conclusion

This chapter has proposed a socially and politically nuanced understanding of land reclamation. In the process, we have seen that reclamation represents not just a claiming of space for private interests but a claiming of space that is difficult for the public to contest and that steers clear of what could ultimately have been socially productive urban contention.