In 2011 Barozzi/Veiga won the international competition for the masterplan of the new Art district in Lausanne, Switzerland – Platform 10 – and the design of the Fine Arts Museum.

Located in the city center, the project proposed a master plan for the city’s three main museums: the Museum of Fine Arts (MCBA), the Museum of Contemporary Design and Applied Arts (MUDAC) and the Photography Museum Musée de l’Elysée.

The site of more than 2 hectares, near the central train station, was mostly occupied by an old 19th-century train hall and some other industrial buildings.

As an urban strategy, the projects implement a new structuring void: a new public plaza around which the museums gravitate. The void stretches along the site and integrates the buildings into the scale of the city fabric; by connecting to the existing train station plaza, they are integrated into the continuity of the city’s public space. The architecture becomes the frame for the urban life of the city, the container of the new public plaza.

The new Museum of Fine Arts is located on the site’s southern edge as a longitudinal monolithic volume, parallel to the rails. Like the train station, it defines an urban space while protecting it from any nuisances caused by the trains.

Embracing this condition, the Museum of Fine Arts, the biggest of the three museums, expresses the memory of the site, echoing its former industrial condition with pragmatic forms, a rigorous geometry and hard, sharp lines. The MCBA is specific to its site; it tries to establish a link with a certain atmosphere, to anchor itself in the city in both space and history.

The opportunity to create an urban void led to the demolition of part of the existing train hall. However, the preservation of the memory of the place is achieved through the preservation of fragments. The project preserves part of the original hall and transforms it into a central piece of the project. In a very classical relationship, the new building of the MCBA acts as a background, highlighting the presence of the old arched window as a fragment, a protuberance and a main feature of the building from the rails.

The overall building is relatively hermetic to protect the museum’s collections; hence it has a closed, introverted façade toward the railroad tracks on the south and a more open, permeable, animated façade on the north.

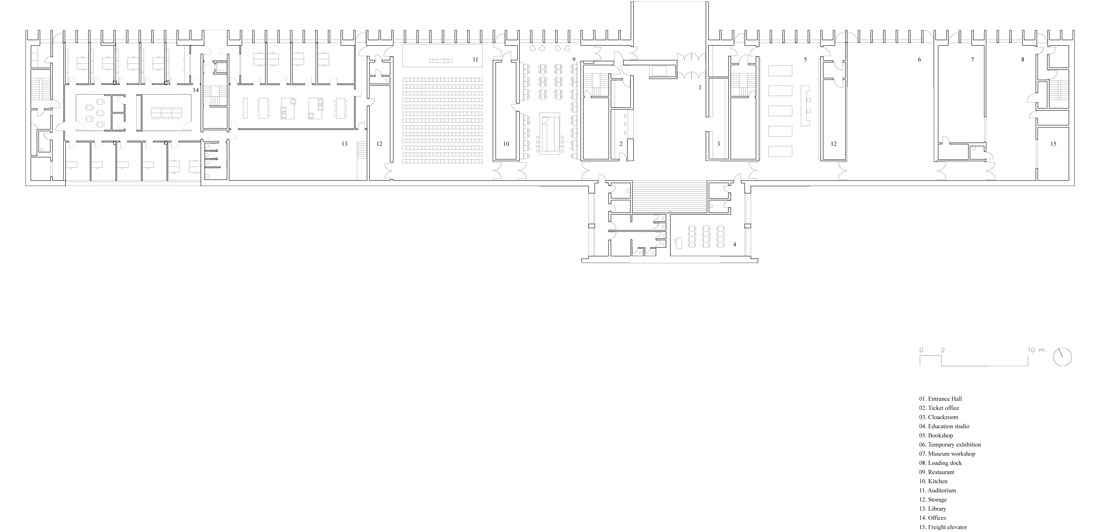

The ground floor was developed as the extension of the public plaza and thus shelters the main social programs of the café, bookshop, entrance, auditoriums, etc. Once within the foyer, the preserved fragment reveals its full role as a substantial structuring component of the new MCBA. Here, the carved arch resonates with the tranquil, double-height space of the foyer and connects it with the view of the train tracks. It also structures the program, organizing the main circulation to the upper floors and separating the permanent and temporary exhibitions.

The complexity of the program is solved in a very simple and synthetic way: five cores structure the program at every level but also serve as structural constructive elements and contain the form of the building.

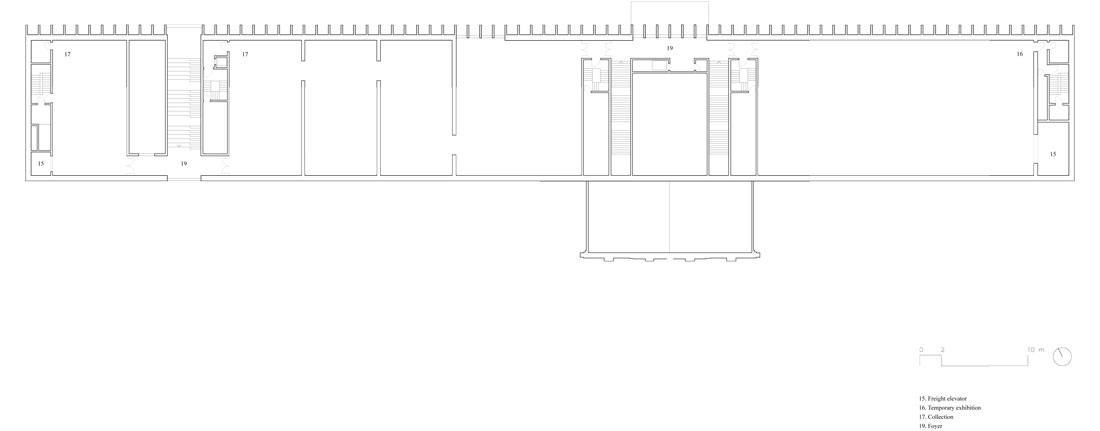

The upper floor is bathed in natural light coming from modular trapezoidal skylights oriented toward the north, diffusing the light and offering optimal lighting conditions for the art.

The museum is organized on three floors connected by the continuous void of the foyer that structures the circulation.

The ground floor contains all the social functions of the program: foyer, bookshop, restaurant, auditorium and temporary gallery for contemporary art. The façade on that level is very porous, ensuring these internal functions are in continuity with the exterior public space of the plaza. On the higher levels, on both sides of the foyer, the exhibition spaces are organized. The permanent gallery in the East is separated from the temporary gallery in the West and can be visited together or in parallel thanks to independent vertical circulations, allowing for future comprehensive exhibitions as well as smaller capsule collections. The connection in the permanent exhibition is conceived as a social and event space: a staircase as an auditorium for smaller lectures or inaugurations.

The building offers two façades: one opaque to the south and a more open and animated one to the north, creating a dialogue with the new plaza. The north façade’s light exposure is minimized by deep vertical fins, with tall large windows in between. The fins are designed to prevent direct sunlight from ever entering the light-sensitive zones of the building. The upper floor is naturally lit from north-oriented modular sheds, designed to filter and adjust the solar light. The sheds possess an internal system of blinds to allow for a meticulous control of the amount of light entering the rooms as well as the possibility of a dimmed atmosphere.

The brick façades evoke the industrial history of the site and offer a texture, a vibrant pattern to the monolith. On the plaza, the rhythm of the vertical blinds breaks up the massiveness of the monolith and reveals the openings. At night, the blinds serve as a canvas to diffuse the light coming from the museum, transforming the façade onto the plaza.

The founding idea of the plaza’s urban design is to create an exterior public space in dialogue with the museums. Like the buildings, it integrates fragments of its industrial past, the rails and the turning plate. Some tall trees will also be planted in order to reinforce its place in the public space continuum with the train station plaza.