To be an urban or rural citizen in China carries vast distinctions in rights and duties. The hukou system was implemented by the Chinese Government as a means to register and classify each citizen as either rural (nonghu) or urban (chenghu), effectively polarizing the populace into lower-class farmers and upper-class urban citizens. The establishment of stringent policies to deter rural citizens from acquiring urban status and the associated benefits has resulted in grave tensions that culminate in the formation of an ‘urban village.’

Unique to China, urban villages are rural villages that once occupied the periphery of large urbanized settlements. Post-1978 sprawling urban metropolises eventually encircled these villages, detaching them from their agrarian source of income. Surrounded by a wall of skyscrapers and infrastructure, villagers are forced to acquire ‘urban’ jobs but cannot do so legally due to their rural citizenship. A census taken in 2000 revealed that 3.8 million rural-urban migrants were living in over 300 urban villages within Beijing. Unregulated and untouched by centralized urban planning, infrastructure construction, and public policy, these urban villages have become de facto independent enclaves of informality. Commonly associated with overcrowding, inadequate infrastructure, social problems and illicit activity, urban villages have become proletariat sponges, soaking up a ‘floating’ populace of rural workers (liudong renkou) to provide cheap labor in urban agglomerations.

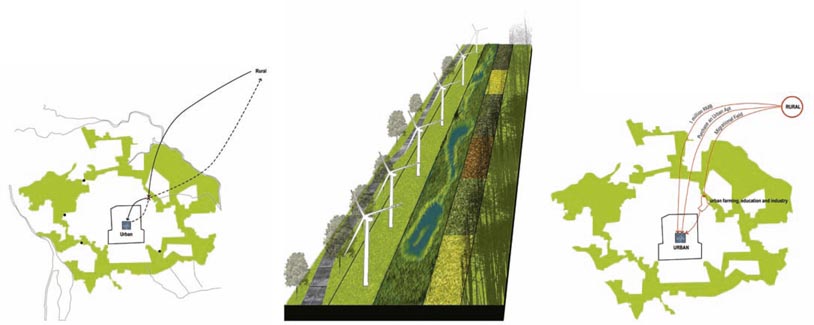

Developers are not eager to transform urban villages, as compensation for ‘agricultural’ land is lower than residential land and resettlement costs are too decadent. Governments have bestowed blame on urban villages for stigmatizing urban development and more recently have encouraged demolishing and replacing the villages, often relocating residents to new peripheries hundreds of kilometers away. The proposed urban design project attempts to foster a symbiotic relationship between urban and rural citizens, creating an interface for exchange as a design template to address the critical issue of the urban village. At the core of the proposal resides a productive landscape that serves to gather the dividing populace.

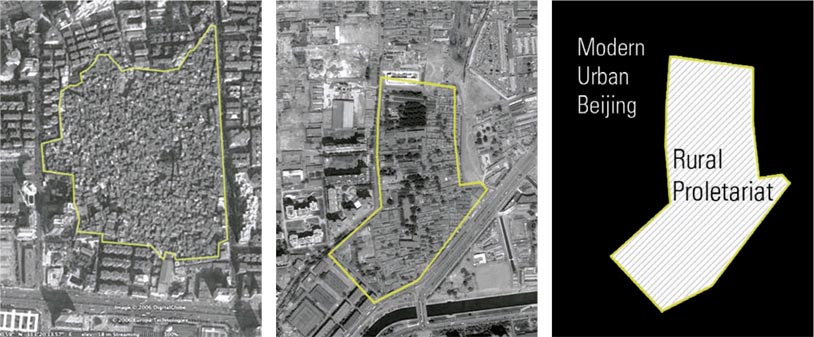

Typical Urban Village (left) and Sun Palace Urban Village (center): Urban islands of the rural proletariat surrounded by modern China.

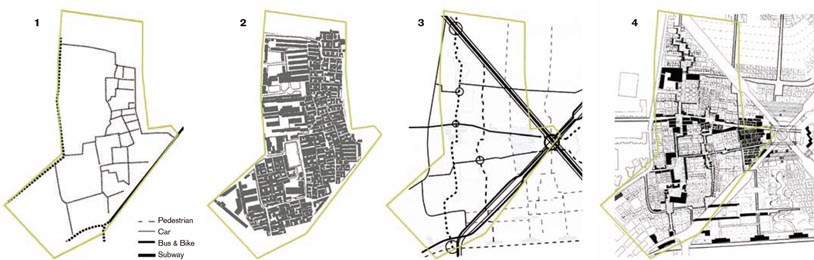

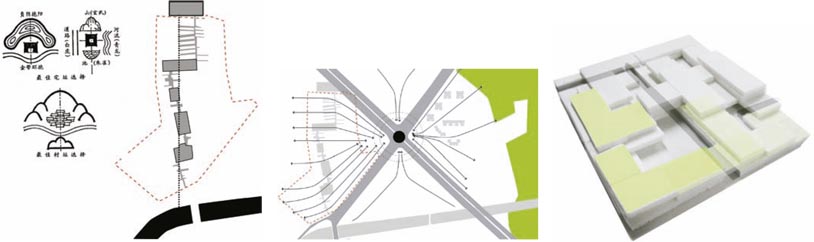

1. Existing circulation; 2. Existing textural form—reveals rice paddy configuration and irrigation canals; 3. Proposed circulation—hierarchy of primary, secondary and tertiary routes based on the farming structure; 4. Proposed textural form and civic structure—textural form is integrated into the rice paddy module while the public civic structure links the existing north-south axis with the new transport station.

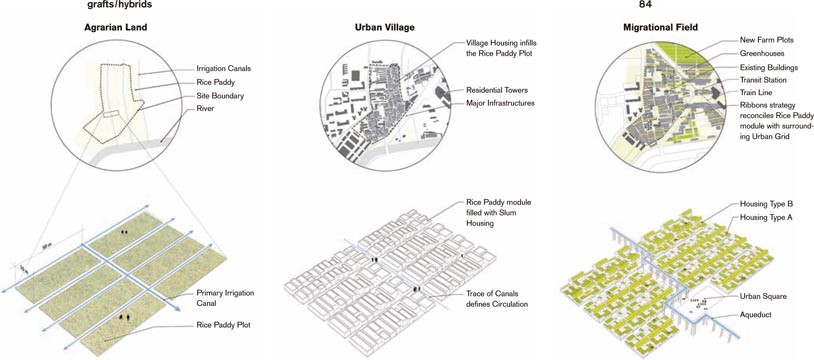

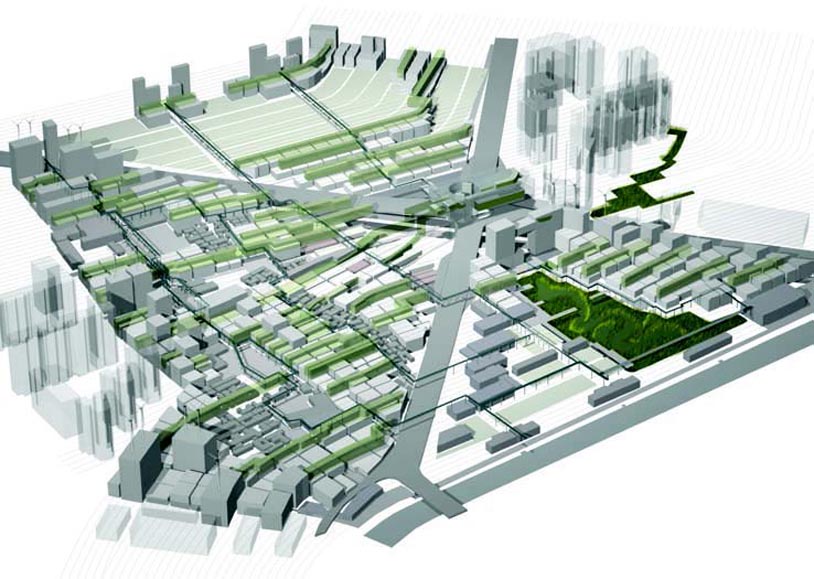

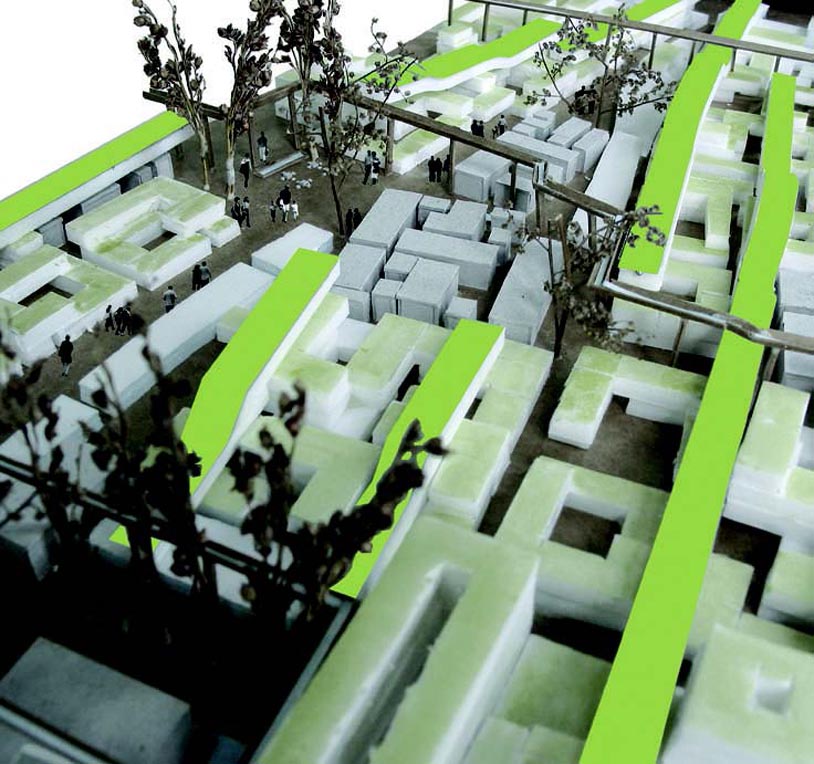

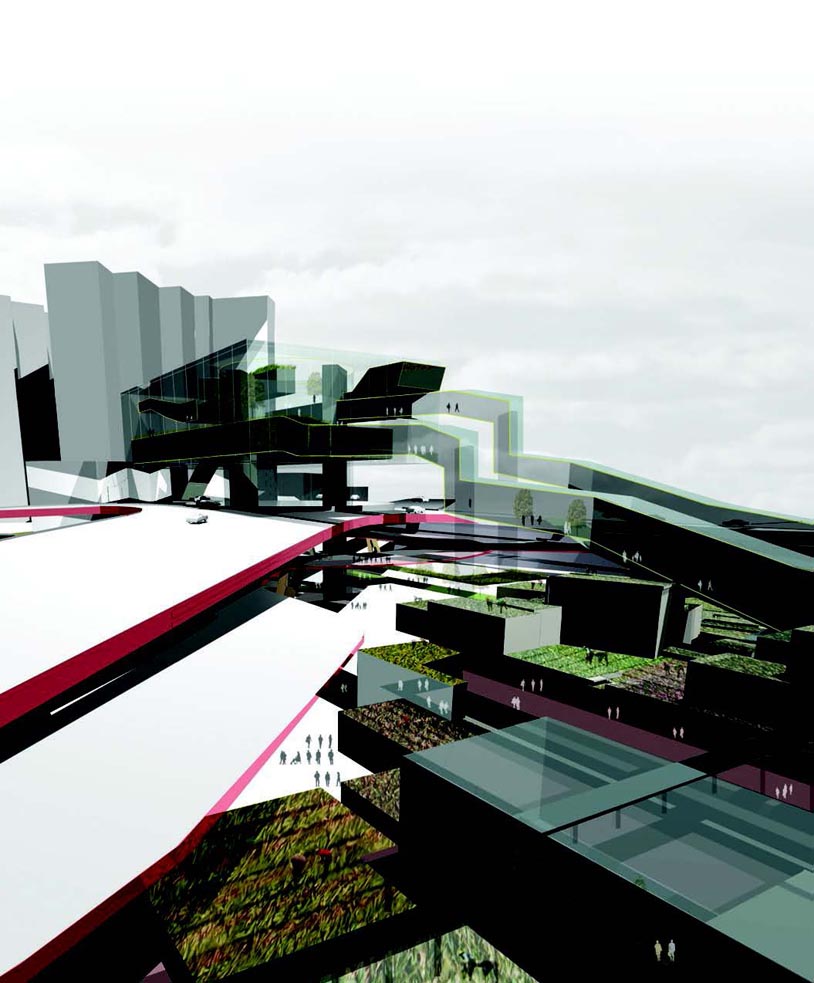

The planned greenbelt at Beijing’s once peripheral zone marks a unique transition between urban and rural landscapes. This outer ring is sprinkled with urban villages that are quickly being encroached upon by new high-rise developments. The urban village located at the intersection of the planned Sun Palace transport station, the greenbelt, and the Bathe River is emblematic of several urban villages, imbued with a tenuous future as the reality of modern infrastructure construction threatens to destroy the settlement. The proposal begins with modifying Beijing’s regional greenbelt plan, differentiating the vast landscape into productive zones — areas to farm clean water, air, food, and energy. These inject productive characteristics into the land that can be monitored, maintained and harvested by rural citizens. The re-establishment of productive land is further explored in the urban village. The morphology of the village as it urbanized reveals traces of its past — dimensions of the rice paddy fields established a critical planning block. Moreover, irrigation canals that once ran transversely through the fields have been replaced by circulatory streets. The proposal utilizes a series of ‘ribbons,’ which mimic the location and scale of the rice paddy configuration, to run throughout the site and mutate to link into the adjacent contemporary block configurations as well as the productive greenbelt. This framework is cut transversely by elevated irrigation canals that organize a series of public streets and plazas into a civic structure of major and minor axes. Laudable existing buildings are given new public functions and incorporated into this hierarchical framework. Three new housing typologies are developed that integrate rooftop farming, high-tech green- house farming, photovoltaic energy farming, and living quarters around traditional courts. These types are dimensioned to the block pattern and can be combined in numerous ways to create a series of topographic conditions — reminiscent of the terraced farms in rural China. The morphology of the settlement hybridizes the natural and artificial, the productive and consumptive, the living and working. One iconic moment, the transport station, serves as a civic indicator of the project, housing a large greenhouse, education, and research center.

Evolution of the site from agrarian fields to urban village (left to right). The proposed scheme hybridizes the productive landscape with the urban structure to create a migrational field of exchange.

New forms of farming and education provide a venue for migrant workers to increase their skills, inviting their potential urbanization. Urban citizens are able to consume the products of the farmers while scientists and horticulturalists learn from those who have vast intuitive knowledge of the land. The urban village is reinvented as a Migrational Field, a place of symbiotic exchange between traditional and contemporary methodologies, production and consumption, natural and artificial, and past and future. China’s growing population requires massive amounts of water, energy, and food — and there is no reason why this cannot be done within the rural villages that have survived the sprawl of modern cities.