Chicago digs deep to fight flooding, but the city’s geology may provide another solution.

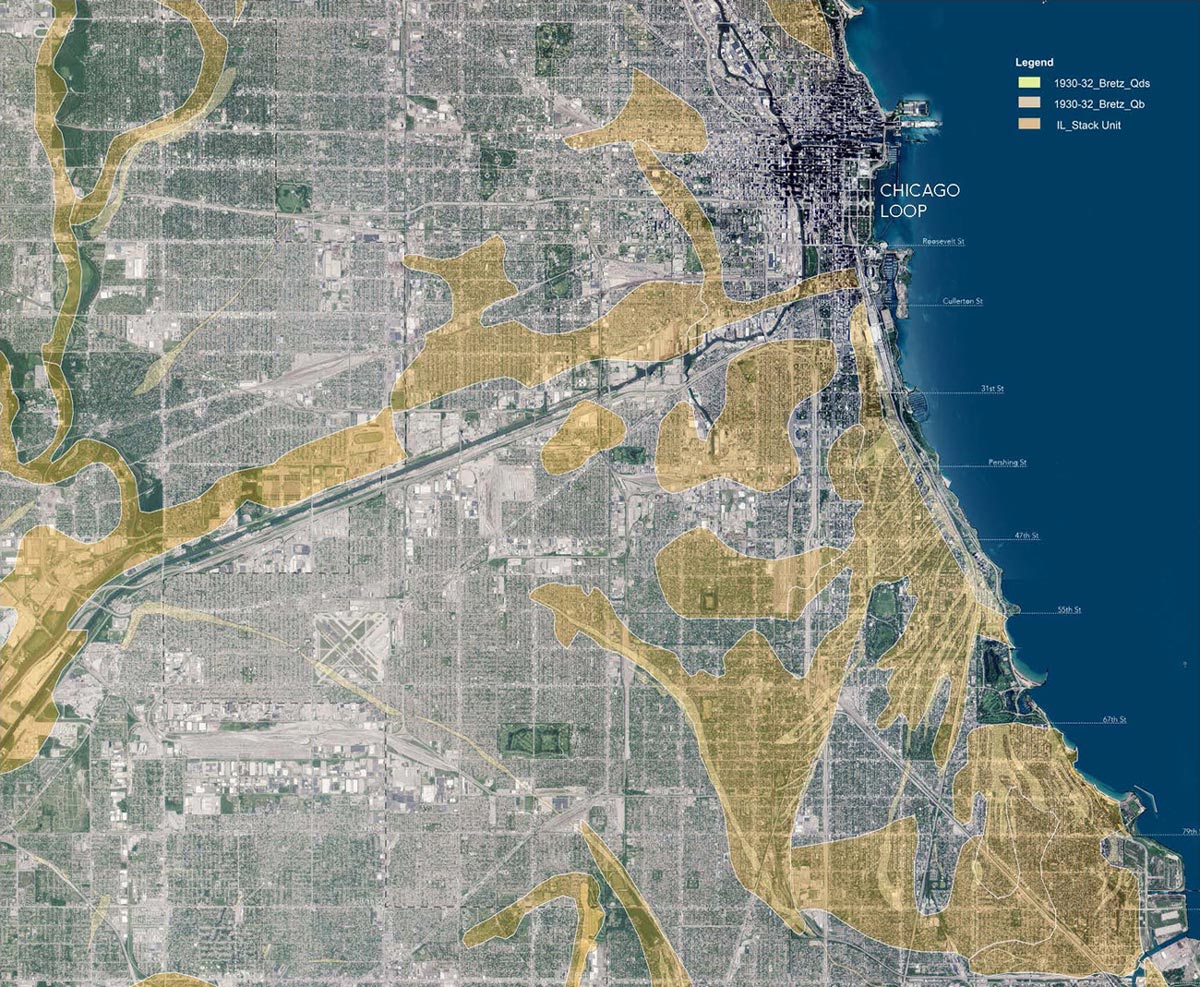

Landscape architect Mary Pat McGuire is working to tap a hidden asset in Chicago’s fight against flooding: Forgotten sand deposits that could absorb rainwater. Coastal dunes were paved over as the city grew, but still exist underground. McGuire drew this map in collaboration with geoscientists from the USGS and ISGS to reveal the buried sand dunes.

When it rains, Chicago faces challenges from above and below: With 25 percent of the city paved-over, rain can’t reach the soil and absorb the onslaught of water. An aging and under-capacity sewer system causes regular flooding and even sewage discharge into nearby water bodies. The challenge is immense—for Chicago, one inch of rainfall equals four billion gallons. Until recently Chicago’s answer to the problem has been an infrastructure project no less than epic—read costly—in scale. But one landscape architect is leading an effort to change how the city can unlock its hidden potential for storm water management.

Chicago’s Tunnel and Reservoir Plan (TARP), also known as the Deep Tunnel Project, is the latest in the city’s massive water projects. Following in the footsteps of extensive canal digging around the turn of the 19th century, the TARP is a 50-year project that started in 1975. Completed 19 years ago, phase one of the project includes over 100 miles of tunnels ranging up to 33 feet in diameter. These tunnels are reservoirs for over two billion gallons of sewage overflow, waiting to be treated. Surface reservoirs are planned to hold another 15 billion gallons when the project is complete in 2029. In the past 30 years, the project has had some success in mitigating the situation, but at a cost of $3 billion so far. Some feel there is another, more immediate way to help at the neighborhood level.

Mary Pat McGuire, landscape architect and assistant professor at the University of Illinois Champaign-Urbana, has been working with her students, geologists and coastal researchers at the U.S. Geological Survey and Illinois State Geological Survey to map porous, naturally occurring sand deposits located just under Chicago’s surface that could absorb rainfall. To find the best test sites for anti-flooding interventions, McGuire is matching the deposits, located along the Lake Michigan shoreline and running up to 25 feet deep, with heavily paved areas that flood frequently. Next, she aims to find local partners—likely community advocacy groups—who will support her to implement design prototypes that could include de-paving, installing dry wells and monitoring equipment, and even introducing new absorbent materials. What would such an intervention look like? “Pattern is going to be an important way for people to recognize that something is happening there…[that] it’s not an accident.” Abandoned or underused sites could also take up a variety of public programming over time. But first and foremost, “the ultimate goal [is] designing water where it falls.”

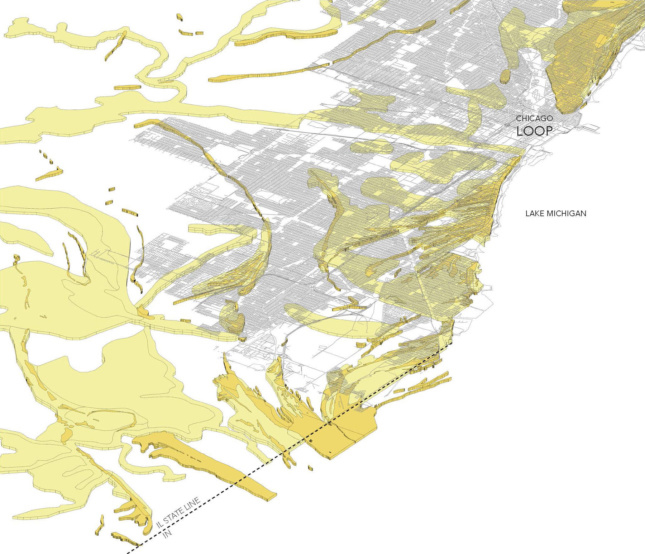

An extended version of the map seen at the top of the page.

Even with the massive TARP project underway, parts of Chicago may not be getting the desperate attention they need when it comes to flooding. According to McGuire, “first Chicago” gets more preferential treatment while other areas are neglected (as documented by flood insurance claims). “There’s an inequity in terms of the ways [city government] is dealing with the situation.” She believes community organizers and alderman in affected areas will need to push for on-the-ground solutions. “If Chicagoans understood the cause of their regular and widespread flooding,” she added, “They might rise up and say ‘City, you’re not providing enough public works for us.’” She argued that working back into the paved surface across the City would alleviate problems for all, including overflows into the Chicago River and Lake Michigan.