A series of small installations in Chile and Bolivia, Latin America.

CCP Pavilion. República Portátil

The pavilion is a transportable building made of wood and located in Independence Square in the city of Concepción, Chile.

The structure, which was thought up by the Chilean Development Corporation, CORFO, involves the creation of a pavilion to accommodate exhibitions and activities related to the productive and creative sectors of the city. These are emerging sectors, and one of their main problems is the lack of connection between them. What is being proposed here is a special setting which is able to gather and receive people and make the meeting place visible within a highly visited urban setting. Once its public service is over, the pavilion will be dismantled and moved to the Concepción City’s Creation and Collaboration Work Center (C3) to welcome other activities included in that program.

The Site

The intersection of Caupolicán and Barros Arana streets, in the busiest square in the city of Concepción, was chosen to generate visibility for the pavilion. It is a highly popular place, filled with historic urban objects, and it is the site for political and religious demonstrations as well. It is a public space that contrasts different social realities and is visited daily by hundreds of people.

The Pavilion

A Foreign Object in a Public Location

A temporary wooden building installed in the busiest part of the city center is, without doubt, considered a foreign object for the people who walk by and visit the square. The natural reaction of pedestrians is to ask what the purpose or reason would be for building such a structure in this location. Moreover, there is a spontaneous effort on behalf of the people who walk near the structure to unravel its meaning.

From this perspective, a number of interpretations and spontaneous explanations are born regarding the meaning of the object, which is transformed into a public event. Possible explanations range from the image of an inverted speaker or a space satellite, which are derived from its shape and try to see it as an object, to the naive interpretation of children as they run inside and see it as a house and a circle to play in, making reference to the wooden edge that separates the center from the outside of the pavilion. But the most common hypothesis that has drawn our attention refers to the Mapuche hut: a vernacular building of the Mapuche people, aborigines from the south of Chile. The most particular thing about this association is that it is not directly formal, because the Mapuche hut is oval shaped, with closed borders and only two entrances, and with a fire inside that produces smoke that comes out through two small openings at the top. This idea obviously contrasts with an open pavilion with 10 entrances, entirely made of wood and open to the sky at its center.

Materials and Structure

In our culture, a wooden structure generates closeness. Moreover, a raw wood truss is a sign of precariousness and self-fabrication. These elements are the manifestation of an intervention using scarce resources, which seeks to explain the precise development in synthetic construction processes without ornaments and superfluous elements that are unnecessary at the moment of developing a structure of this kind. These elements are interpreted as something close to people’s lives, reviving a primitive image. Whoever enters the structure imagines that it could easily be replicated by his or her own hand with no need for fancy or foreign technologies. It seems that everything that is present before people’s eyes is nothing but the reinterpretation of constructive ways that have always been present in our culture.

Pre-Manufacturing Process

The building process of this structure is the development of a series of pre-made elements formed by smaller pieces. These elements are: trusses, flooring, and coatings and linings, as well as a series of individual pieces like crossbeams and beams. For the construction of the trusses, floors and linings and coatings, a series of large scale arrays were developed, on which the prefabricated elements were armed in order. The benefits generated by production based on matrices for prefabricated structures result in a mechanical process that reduces working time and does not require specialized labor for its implementation.

Once prefabricated units have been built, the pavilion can be assembled. The bottom of each piece is verified and once the process of labeling the parts is done, then it is disassembled and stored for transportation and subsequent installation in its temporary destination located in the city center. Approximately 30 days later, the pavilion returns to C3 Creation Center and stays there indefinitely.

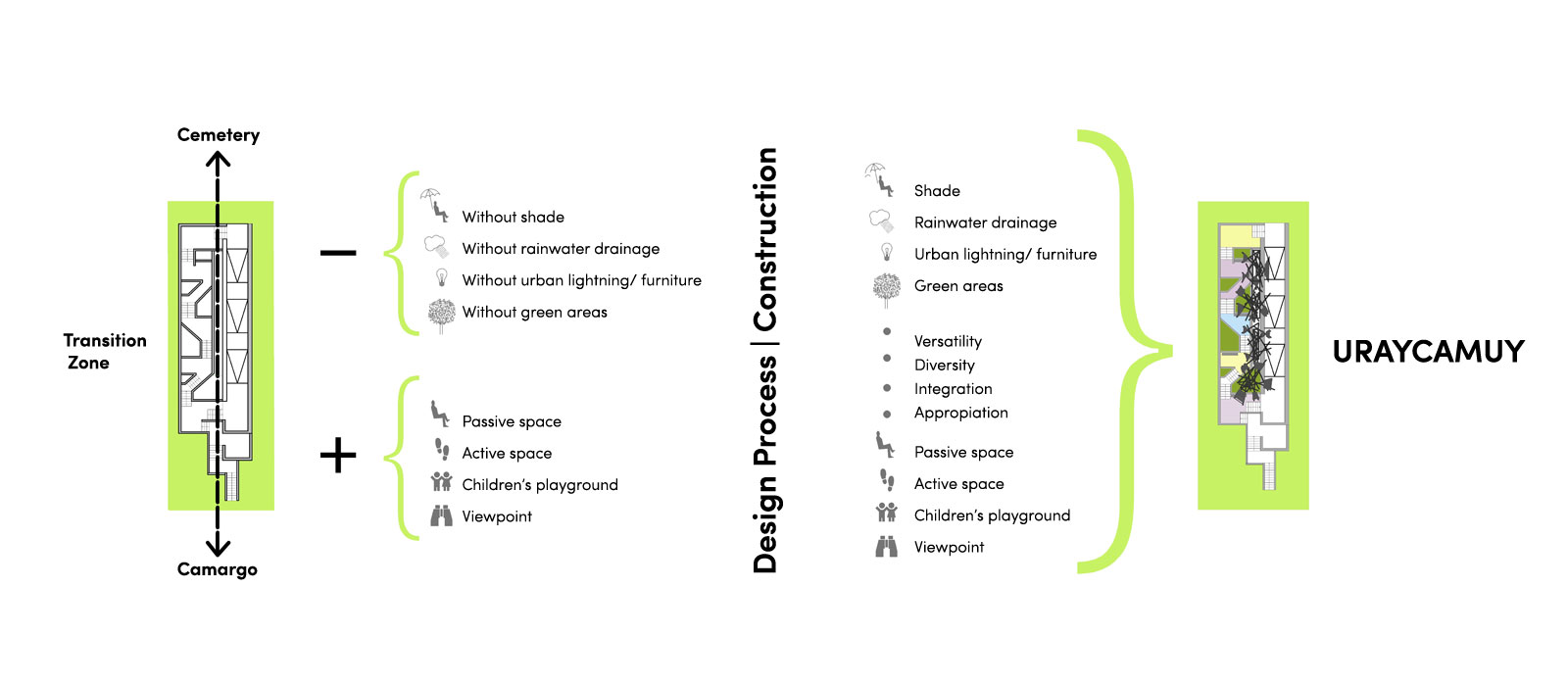

Uraycamuy. Javier Maradiaga, Lara Plácido and TSL2015

The intervention focused on the area known by the locals as “El Tobogán” (The Slide) located in the southwest of the city and it was implemented with the aim of creating a transitional pedestrian area between the city and the cemetery. This space accumulates two functions: it is both a slide intended as a play area for children and a path that alternates assets and liabilities organized into levels to overcome the height difference that separates the city from the cemetery. The first visit to the site showed an amorphous space that was not integrated into daily life by the people of Camargo. People did not use the space because it was neglected, it had no vegetation and it offered no comforts as a living place or a viewpoint. Besides, it was extremely exposed to the sun, which made it an inhabitable space in the hottest hours.

URAYCAMUY | TSL 2015 – Bolivia | Camargo from Lara Plácido on Vimeo.

The team agreed that the purpose of the intervention should be to recover the space, to encourage recreational activity, which contributes to both physical and mental development, and to create a space with features to characterize its context and recover the local identity. Contact with the community was constantly sought to strengthen the role of the architect as an intermediary between citizens and the built environment – the city. In addition, it was suggested that the work should be carried out with the support of the community in the form of ideas, materials and equipment, which allowed them to integrate the construction work, and fostered the re-appropriation of the public spaces.

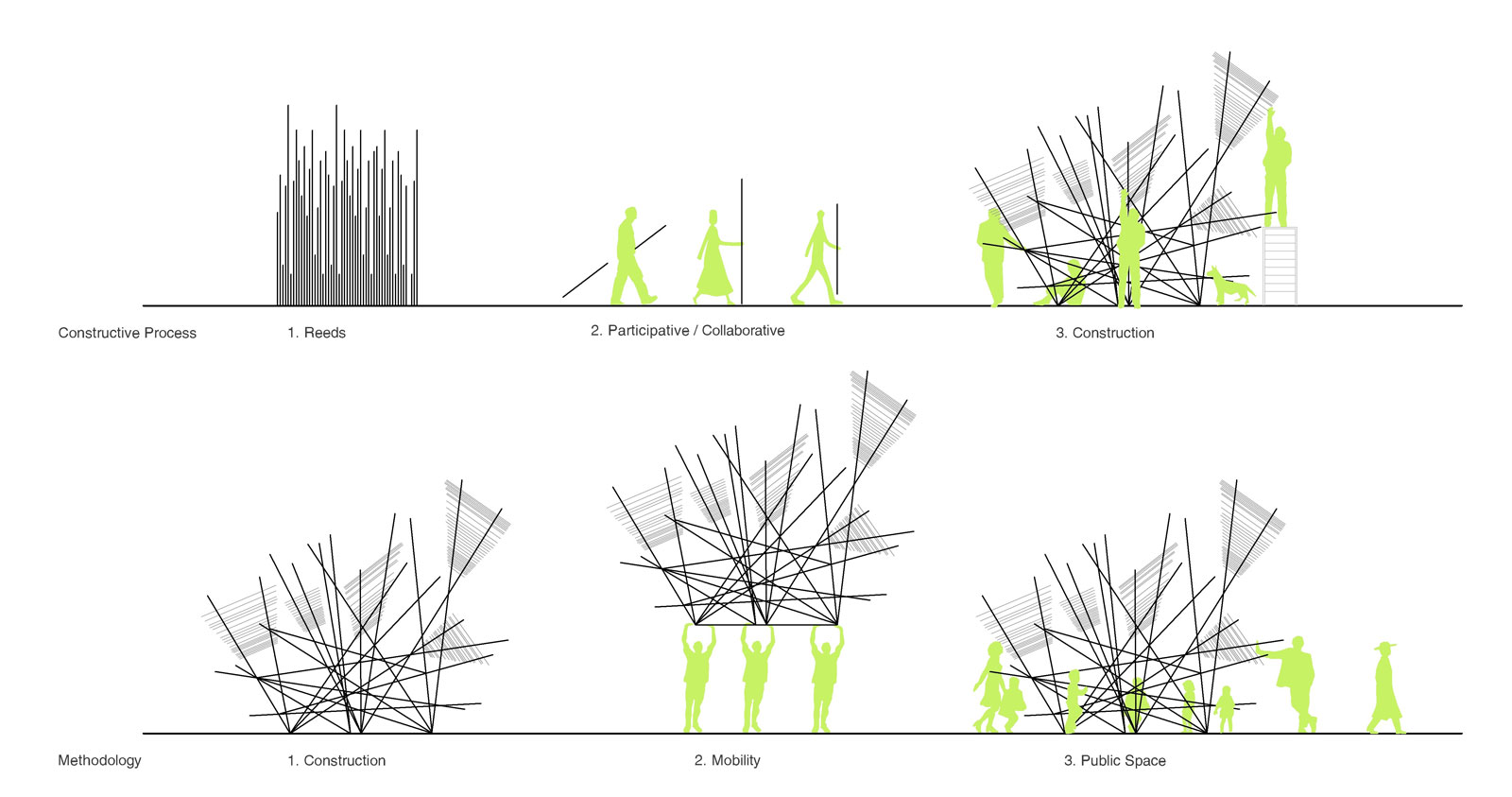

Students developed analysis exercises in the urban context and with the community’s help through site visits, identification of materials and vegetation from the area, interviews, discussion and consensus. The final concept and line of work for the intervention proposal was generated from these exercises. A reinterpretation of the line, which is a constant natural landscape of Camargo and is brought into the built urban context, led to the construction of a structure using reeds as the primary material. The reeds were placed randomly and were united and strengthened by wire leading to the creation of structures with different shapes, heights and shade effects. Wood, stone and vegetation of the area were added to the reeds as complements.

By being in contact with both the community and the intervention area, the students identified the space as a potential generator of different uses throughout the day. In a first stage, students challenged the locals by transforming the City – Cemetery transition space into an outdoor cinema. The acceptance was significant, which proves the potential of the regenerated space. In a second stage, the challenge was to intervene in public spaces, in this case the central market; there was a presentation of the concept to measure the people’s reaction. Once again, the response was positive — the locals identified with the material used (the reeds) and praised the dynamic volumes of the proposal, as well as the shade created by this structure.

Concept

Process

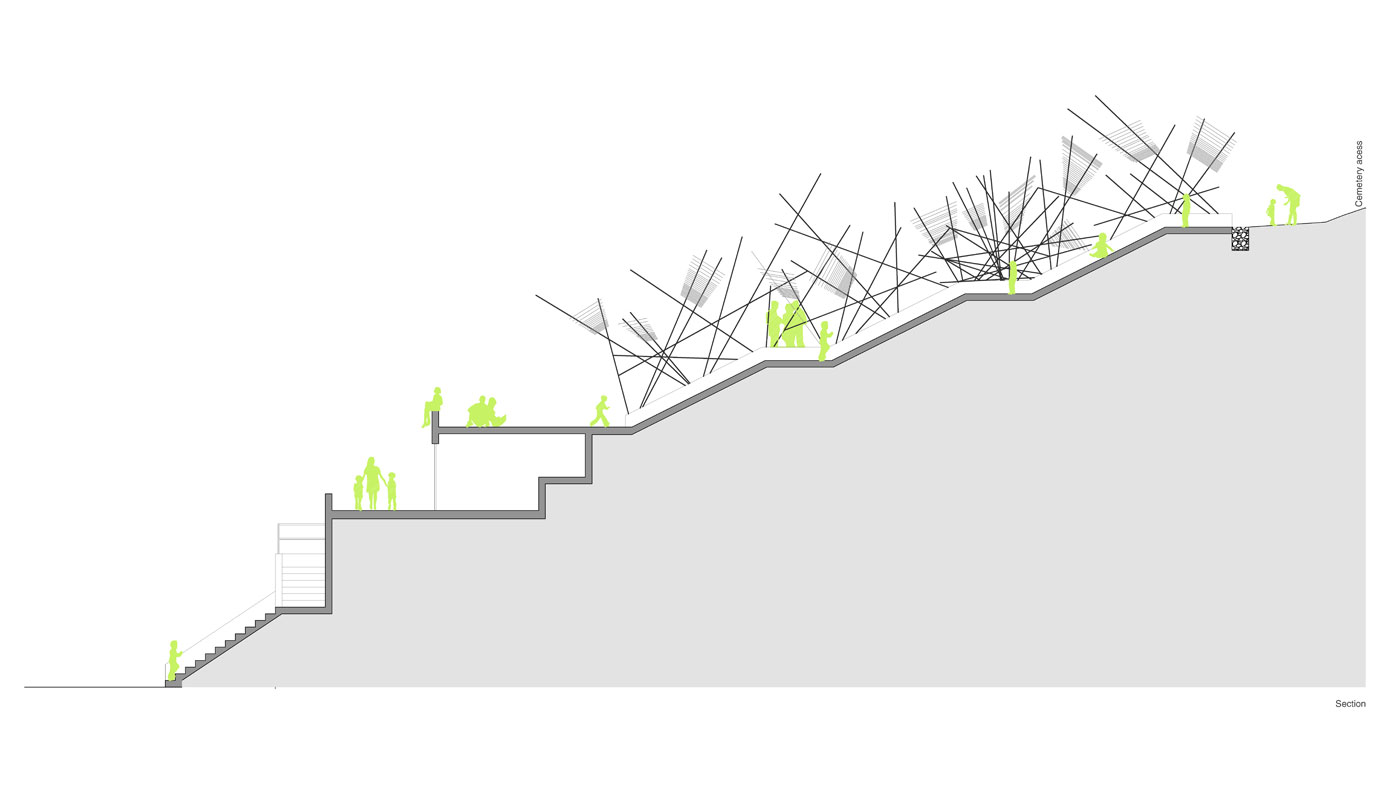

Longitudinal Section

Uraycamuy [1] emerges as an intervention in the built environment, which generates and regenerates flows and new dynamics. With a renewed image that is functional, integrated in the context, and identifiable in different parts of the city, it is also permeable and coordinated with other sectors that communicate and connect with it. The proposal not only reinforces the recovery of the character and use of the space; it also fosters the appropriation of the space by the people of Camargo.

[1] Uraycamuy means “going up and down” in Quechua.

Hikers’ Shelter. Hans Kubat

Valley of the Condors. This place was given its name due to the large number of birds that fill its skies. The place plays with a constant duality: on the one hand, there is the majesty and beauty of its landscapes; on the other hand, there is its inhospitable climate and sparse vegetation, which makes it an uninviting place for climbers, a sporting community that uses that landscape as a platform for its activity and frequent visitors to the area.

Valley of the Condors, an Andean area in the comuna of San Clemente, the seventh region in Chile, more specifically on km 136 of CH-115 which connects Chile with Argentina.

This area has high potential for sports uses, not only in for mountain climbing, but also for sports such as snowboarding, skiing, motocross, fishing, etc., which are currently in danger due to the encroachment of hydroelectric companies that are exploiting the valley indiscriminately.

With its obvious majestic beauty, the valley has been gaining visitors in recent years, and it is more and more common to see people walking through the attractive landscapes.

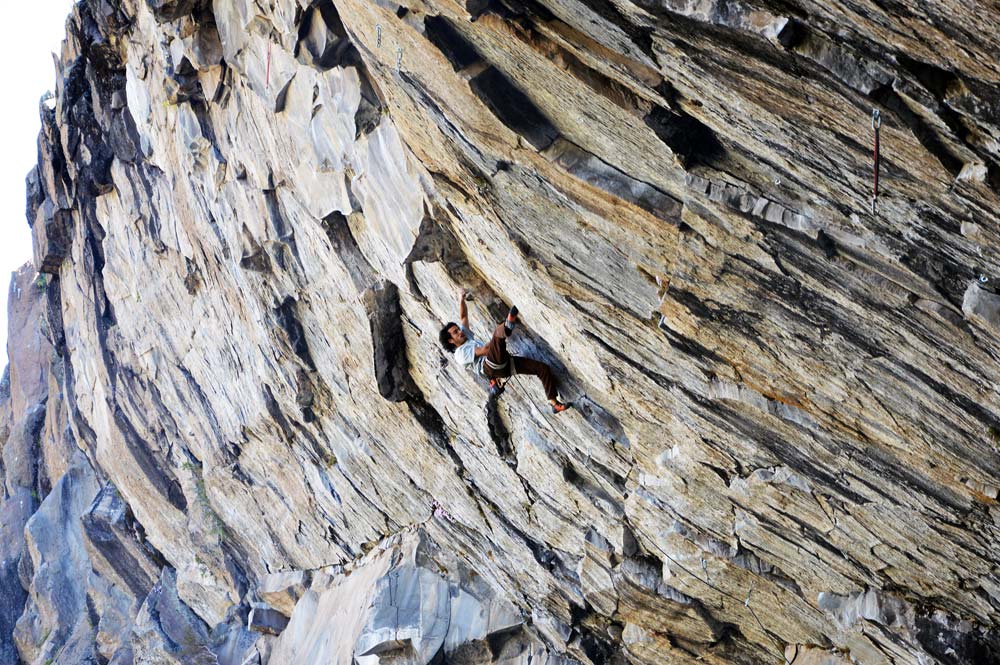

Climbers

The community of climbers is not only present in the area of the Maule valley. Climbers from all over Chile and abroad visit our valley, drawn by the quality of the rocks and the multiple possibilities offered in the area for practicing the sport, from traditional climbing to competition climbing, bouldering, high bouldering, etc.

The valley is so big that there are still unexplored areas with an enormous potential for high-level climbing. That is why the community of climbers is especially concerned about maintaining the area and keeping it clean, emphasizing the need to care for the mountains.

Given the aforementioned conditions, the problem emerges: How can we support the activities of that sporting activity with an infrastructure that can be used both in the winter and in the summer.

The solution: the construction of a shelter that can provide adequate conditions to its users in periods where they need shade, or to build a fire, etc.

The method: dismantling a forgotten infrastructure – a shelter located at km number 124 along CH-115, abandoned by the MOP after the construction of the road, in a deteriorated state. The material will be sorted and moved 10 km toward the border with Argentina, where it will be reborn through the efforts of its intended users – mountain climbers – thus consolidating a place with a high potential for sports activities, but which has been invaded by hydroelectric power plants. The shelter proposed its own dismantling not only as a temporal renovation process, but also in terms of space, form and location.

Dismantling an Abandoned Infrastructure

Time-lapse video showing the first part of the project, which consists of dismantling an abandoned shelter in the Andes of the Maule region, with the aim of reusing the material in the construction of a new shelter, located some 10 km higher up, along the CH-115 route that connects Chile and Argentina. That way, the building can provide shelter for a community of mountain climbers, a roaming community that has been gaining members of time. The idea is also to effect a change in shape along with the movement of the material, adapting the construction to the adverse climatic conditions of the new location.

Land: Belonging to the 16th Regiment of Talca after the expropriation of land to pave the road.

Shelter: Originally, the shelter was a storehouse belonging to the MOP (Ministry of Public Works), which was used during the construction of CH-115, Pehuenche Pass. When the construction was done, this infrastructure was abandoned and was eventually consolidated as a shelter used by mule drivers and tourists.

Elevations & Sections

Plans

Assembly: Re-use of the recycled material, birth of a new place

Time-lapse video showing the second and final part of my degree project, consisting of the construction of a high-mountain shelter in the Valley of the Condors (San Clemente, seventh region, Chile). No qualified laborers or professionals were hired. The future users of the construction – the community of mountain climbers – were responsible for building it with their own hands.

Land: Owned by the department of Public Heritage and categorized as protected Public Heritage, the land was ceded for the construction of the project, for the purpose of promoting sports activities in the area.

Hikers’ Shelter

“By modifying the sense of the space crossed, walking becomes man’s first aesthetic act, penetrating the territories of chaos, construction an order on which to develop the architecture of situated objects.” Careri, F. Walkscapes: Camminare come pratica artística. Torino: Einaudi, 2006, pp. 3-4.

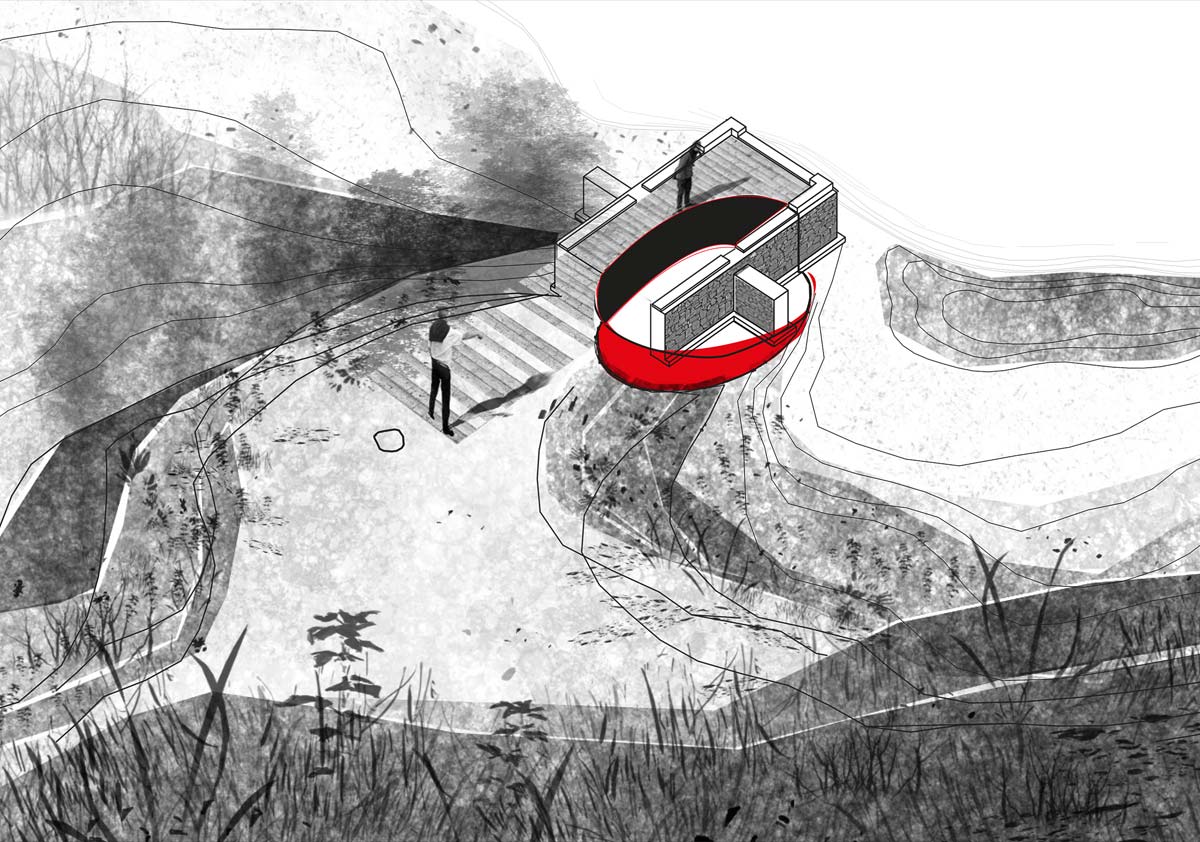

El Litre Memorial. Matías Leyton

“Memorial el Litre” was designed in the context of the degree program at the University of Talca School of Architecture. Located in the north of the Maule region, in the hilly town of Los Queñes, the project focuses on one of the central relationships that has given the site its identitiy throughout its history: the bridge as a point of connection and a public infrastructure that provides access to the town, and to the river, and as a part of the landscape that facilitates different activities, mainly leisure activities on the riverfront.

The project is located among the remains of what was the first bridge into the town, which initially gave rise to this relationship between the bridge and the river. It was also the location for the first river leisure area used by the residents and visitors to the town. As such, the design is proposed as recovering the ruins. While evoking the aforementioned past, this allows for rebuilding a part of the collective memory, taking advantage of the structural foundations and uncovering an abandoned stretch of road.

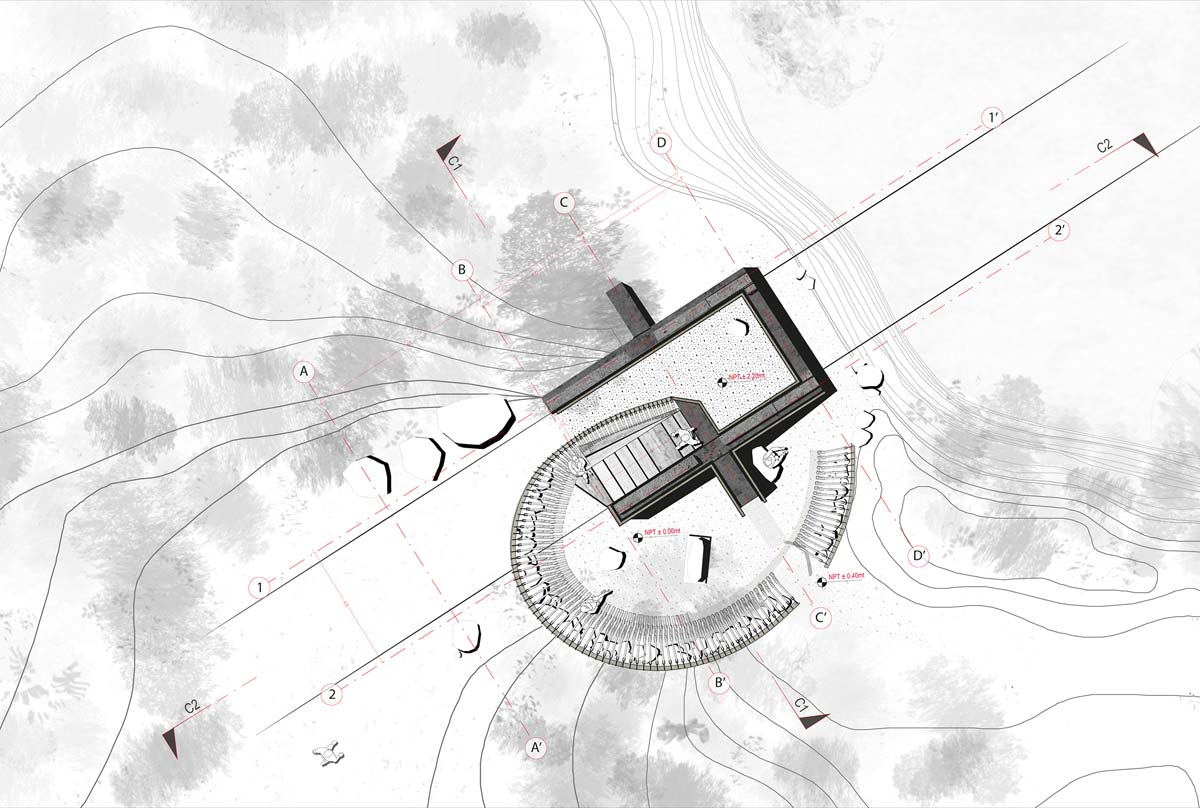

Site Plan

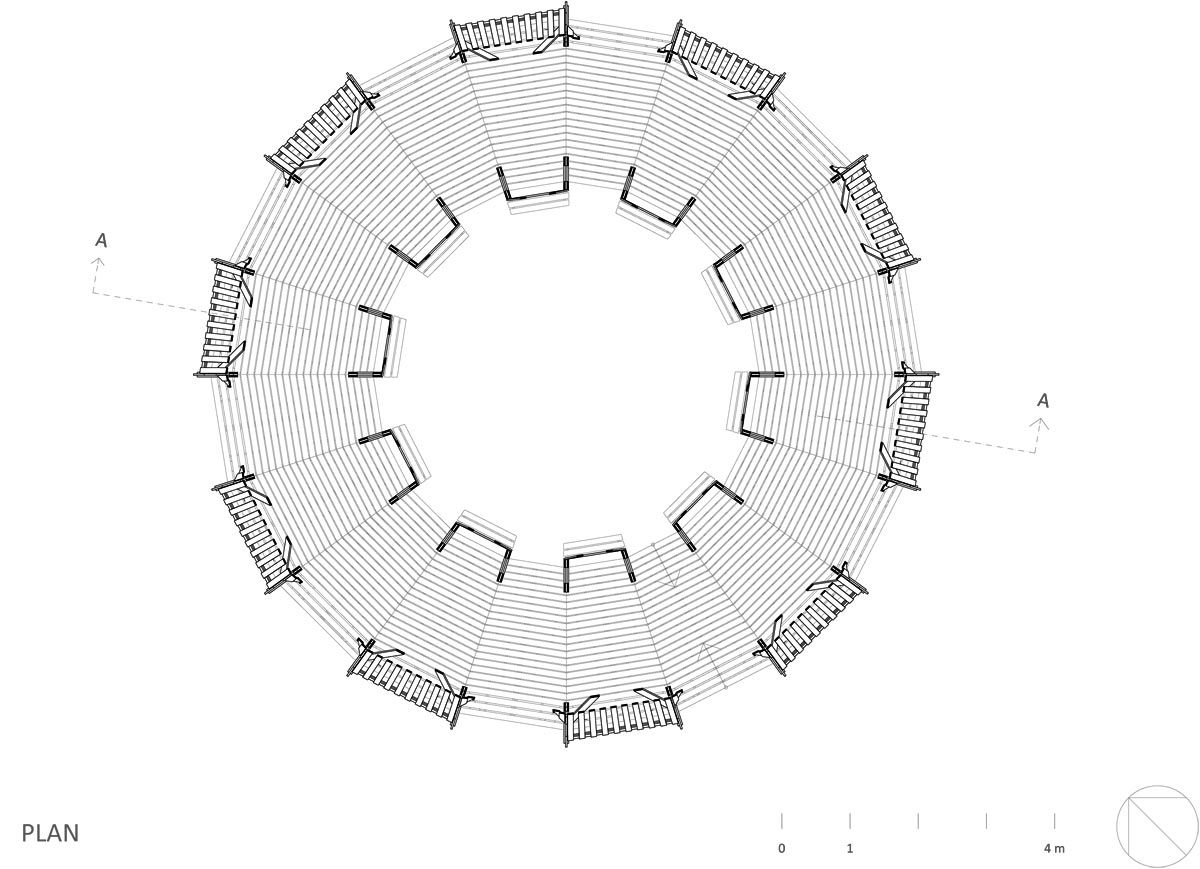

Plan

Sketch

This exercise in heritage recovery takes up the ruins of the past to infuse them with new life and a new function, returning them to their original function as a public space.

Based on recovering this pieces, the occupation works as a repair process, in which the extraction and cleaning of elements is one of the main elements of the project. The aim is to dig down and occupy the heart of the ruins and to reveal what is hidden and give it visibility, using the ruin as a raw material in its new condition, as opposed to a mere monument of the past.

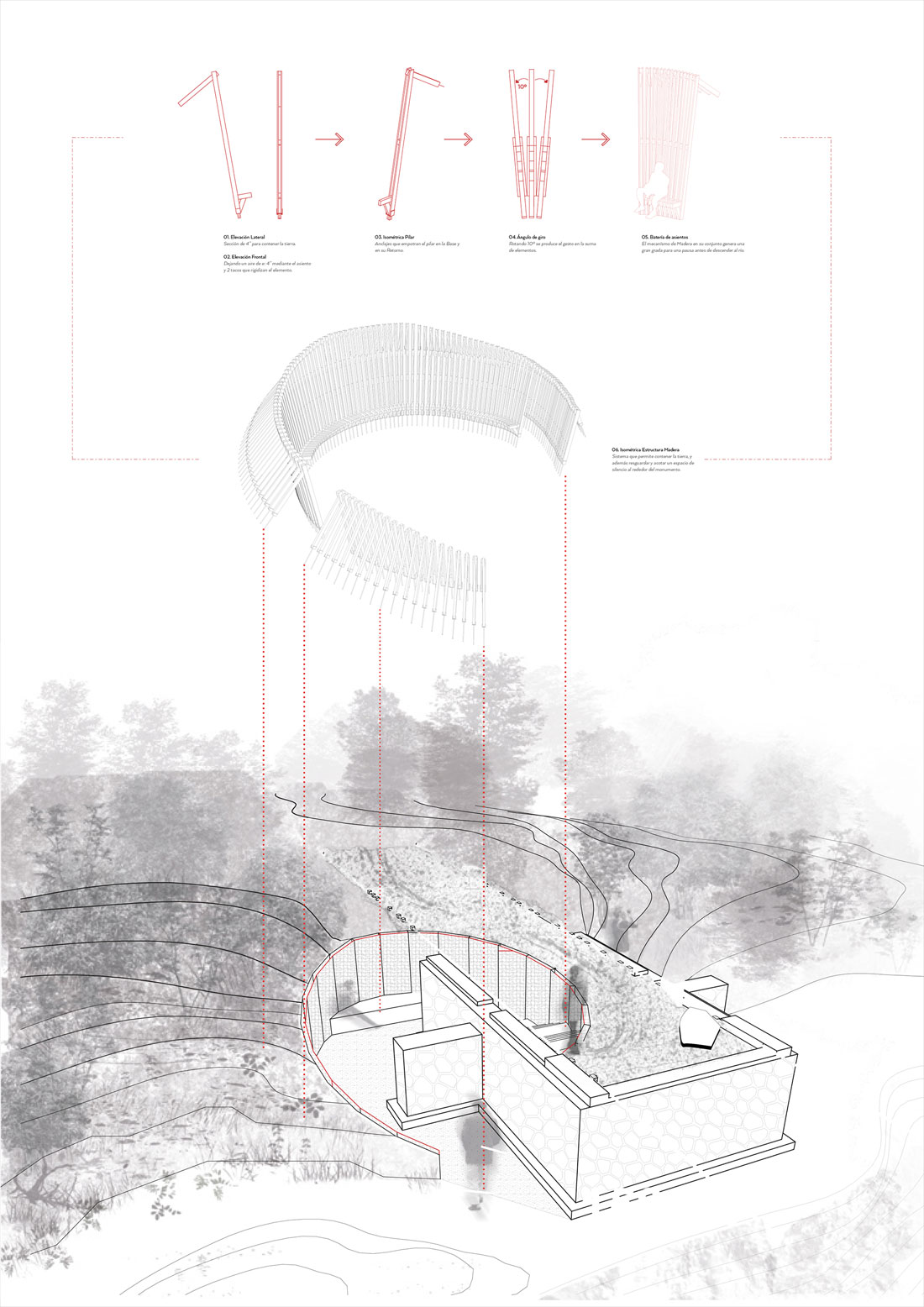

With the aim of preserving and protecting the ruins, the central focus of the proposal is rooted in contrast, to differentiate its materials, form and height from the original construction, respecting the glory and strength of the monument as a support for a bridge that is has disappeared in time. The project proposes preserving the fragment through limits that do not touch the older elements, leaving the staircase as the central aspect that joins together both languages and leads to new itineraries.

Diagram

Finally, to emphasize the act of extraction, a limiting mechanism is used along the perimeter of the intervention area. Using 104 wooden pillars, a system is created to contain the earth while protecting and outlining a silent space around the monument. This new border, orients and accompanies the route around the ruins and serves as a bench for taking a break on the way down to the river.