Comfort is the energetic and symbolic nexus between citizens and cities. It simultaneously describes the thermal relationship between a body and its environment, and the social one between the individual and larger groups. Architects are professionally predisposed see buildings as the primary context for comfort. Yet, shifting focus from the building to the body highlights how clothing responds to and shapes contemporary notions of comfort in ways that buildings cannot. The dominant concept of thermal comfort that developed during the twentieth century relies almost exclusively on conditioned air within sealed building envelopes. This air is kept at “ideal” steady-state conditions so that an average body maintains homeostasis with the interior climate without the occupant’s conscious attention. Yet, comfort is not the result of a simple interplay between the body and an enclosed volume of air; instead, it results from the dynamic energetic exchanges at the narrow boundary layer around the skin. Clothing, not air conditioning, is a principal mediator of such comfort. Exploring this energetic boundary focuses attention on the beginning of a new approach to comfort and the end of air conditioning.

Driven in part by global climatic instability and a focus on energy use, attention to comfort is increasing. Architects typically bracket comfort within normative practice, focusing on improving the efficiency of materials and systems we already use.1

We are trapped in what we have typically done.2 Shifting focus from air to clothing as a principal means of providing comfort opens new lines of inquiry, and presents new opportunities for rethinking the relationship between design and energy at personal, architectural, and urban scales. Clothing is a visible register of our expectations about what types of climates we expect to find ourselves in, and what kinds of comfort we hope to achieve there. It embodies fine-grain modes of expressing and shaping our relationship to buildings, cities, and the changing environment. It is nimble in ways that buildings are not. Unlike buildings, clothing is a dynamic element in the overall environment. It doesn’t distinguish between inside and outside climates. It can easily be changed based on external factors like location and season, or internal ones like age, gender, activity level, or personal preference. Clothing can address climate variability in real and visible ways that link physiology and fashion, individual and collective, inside and outside. It can help to turn the idea of climate from an abstract, statistical index to a lived experience, giving it agency to connect social habits with meteorological phenomena through design.

Skin Is a Thermally Active Surface

Skin is the body’s original thermally active surface. Compared to skin, clothing and buildings are relatively recent inventions used to mediate the relationship between the body and its environment. While clothing and buildings emerged over the last 40,000 years, the body’s thermoregulatory mechanisms developed beginning with the emergence of the genus Homo around 2 million years ago.3 Since then, the body’s thermoregulatory system has developed into its current state through the slow process of biological evolution. Much of its control is involuntary. The thermoregulatory process begins as information about temperature at the body’s surface is transmitted from thermal receptors in the skin through the nervous system to the brain’s hypothalamus.

If this temperature is outside of the desired range, the body involuntarily responds by regulating heat production and distribution.

In the case of excess heat, this happens through vasodilation, where blood vessels in the skin expand, allowing heat, carried by the blood, to be moved from the body’s core to its surface where it can easily be moved out of the body and into the environment through the different modes of heat transfer. In the case of excess cold, the opposite happens: the process of vasoconstriction reduces blood flow through the skin, thus conserving heat in the body’s core. The body can also shiver to produce additional heat through metabolic combustion in the muscles. The goal of this thermoregulation is homeostasis. Homeostasis is the ability of an organism to maintain a stable internal environment despite external influences. On a functional level, all adaptive responses of an organism—involuntary or voluntary, internal or external—are made to restore internal homeostasis.

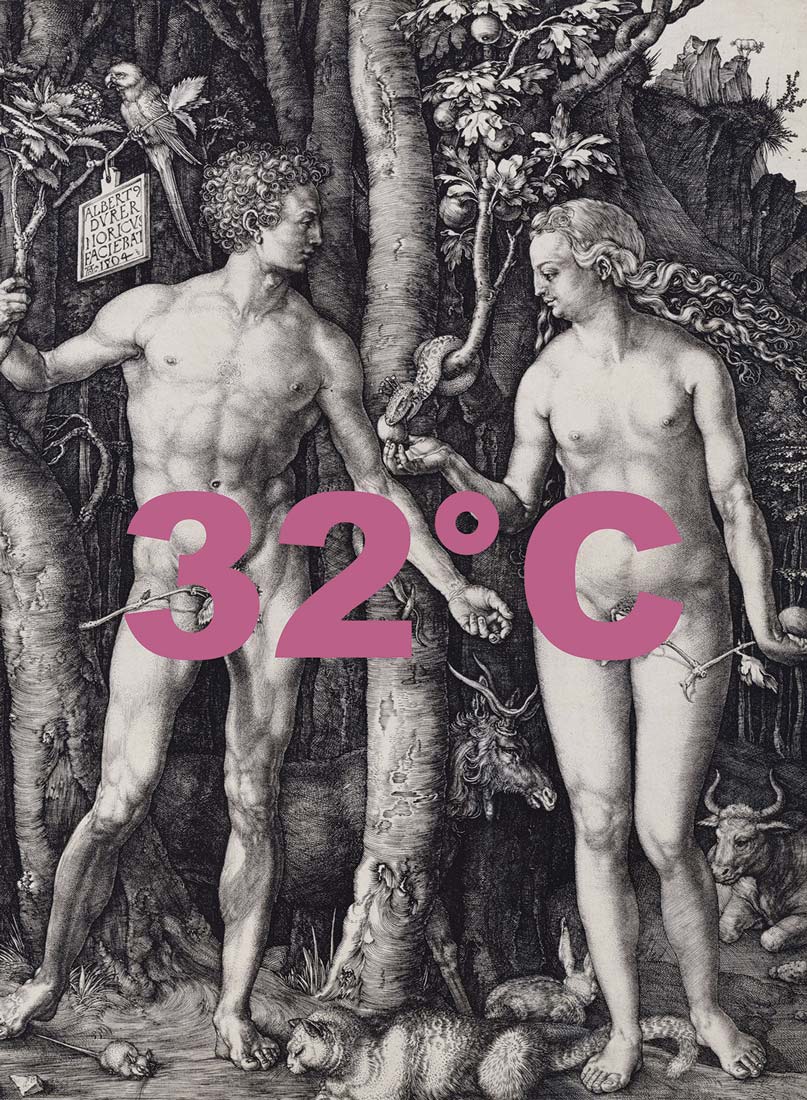

Adam and Eve in the Garden of Eden, where the climate was in perfect harmony with the body’s surface temperature of 32°C. [Based on Albrecht Dürer’s Adam and Eve (1504)]

Mythical paradise settings often assume a harmony between the body’s internal environment and the external one. In the Garden of Eden, Adam and Eve needed neither clothing nor architecture as the outdoor climate was ideally suited to the comfort provided by their exposed skin. Only after their Original Sin, when they were cast from the Garden, did such external means of controlling comfort become necessary for protection against original climate change.

Although it builds on the biological evolution of the body’s thermoregulatory mechanisms, the modern history of comfort is more determined by the cultural evolution of clothing and buildings. Unlike the slow process of biological evolution that passes through genes from parents to offspring, cultural evolution can be passed among multiple sources. As such, it’s a faster, more potent form of change. In the case of clothing and buildings, cultural evolution ameliorates or negates the effects of the environment on the body, thus buffering the body from the effects of natural selection that might otherwise occur.4

Clothing is used outside of the skin to extend the body’s range of thermoregulatory control, and to reduce the metabolic cost of this control. Although buildings are used largely for the same purpose, there are some important distinctions between them. While clothing’s interaction with the body’s physiology happens at the surface of the skin, buildings typically rely on large volumes of conditioned air, only a small part of which is needed to provide thermal comfort. As buildings become larger, smaller percentages of this air is used to meet the body’s needs. Clothing can provide thermal comfort regardless of climate or enclosure. It can be used inside, outside, and anywhere in between. Buildings, on the other hand, rely on a clear separation between inside and outside in order to effectively condition the air that they contain. In fact, the very idea of modern thermal comfort in buildings is based on this separation. In privileging the building-based comfort model, architecture reduces the potential for clothing-based comfort.