In contrast to other public or private parties, the Carnival does not understand about classes. The Carnival has a civic component; it democratizes the space in which it is celebrated. Everyone — regardless of their social or economic status — is on the same level. Students from private universities and public high schools dance mixed in the same place because they are no longer students, but firemen, octopuses, pharaohs, or fairy godmothers. There is no place you cannot enter because dancing takes place on the street, and VIP areas are pointless. After all, the fun is where the crowd is.

However, this construction of collective identity based on dancing and agglomeration is very brittle. Over the last few decades, this celebration model has experienced some wear and tear, losing its glamour to fancier and more exclusive parties, ceding public spaces and its protagonism to monetized private initiatives. In addition to that, recent digital socialization trends, accelerated by the current health situation, ended up dynamiting an already weakened model.

The Garden of Attractor Sounds – Photo María Galindo.

Spaces of Representation: The Rave and the City.

Alternative spaces of celebration are born as a place without a place. A space for the representation of “individuals whose behavior represents a deviation in relation to the required norm.”[1] These spaces settle on the margins of a society that excludes them, on the other side of the mirror of the imaginary utopia of a society in which they are not welcome. These spaces, far from having common physical characteristics, can vary in size, shape, and location. However, they become clearly defined by their social component.

During the late ’60s, in response to the continuous police harassment in gay bars and dance clubs of New York, David Mancuso decided to start throwing parties in his own home, a formerly abandoned warehouse. The Loft, a party with a name that embodied its location’s domesticity, becomes from 1970 onwards a common space of representation. The Loft was a gathering of “the disaffected and disenfranchised,”[2] a place where a multiplicity of identities could meet freely on weekends to the rhythm of Mancuso’s vinyl records. With the best sound system in town and the dance as a catalyst, the party became a democratizing element that invited people to participate in a shared experience, which was more than unusual at that time: “blacks, whites, old, young, straight and gay in the same room.”[3] We could say, therefore, that the home comprises the first circle of representation; it is in the domestic space where we first find a safe environment for manifesting personal identities. “A lot of the guys who came to the parties had rough lives on the outside.”[4]

In response to nightclub exclusivity and the limitations of domestic space — to which not everyone has equal access — the party finds a middle way. Abandoned industrial warehouses, former war bunkers, or wastelands under the highway are, among others, suburban spaces that host celebrations outside the official leisure model. These places, generally located on the city margins, were not designed for nightlife fantasy at all. These suburban locations, characterized by their ambiguity, occupy a position on the edge. Both transitional spaces — such as a bridge or a parking lot — and those in an intermediate state — such as an abandoned warehouse or factory that are no longer producing or goods — acquire a condition of liminality.

These liminal spaces, we could say, comprise the second level of collective representation. They are typically used for hosting parties that are divergent from ‘the norm’ and could not be celebrated elsewhere. It is precisely in these spaces, which escape modernist dual oppositions, where identities that do not fit into the hegemonic binary discourse because of their race, gender, ideology, or class find a common space of representation outside everyday life conventions. Opposed to a utopian social order, they belong to what Foucault called in his essay Of Other Spaces, Heterotopias[5]; specific social spaces whose functions are different or opposed to others. On the one hand, they become places of resistance that host contestation to an oppressive reality. On the other, these social spaces construct an alternative spatiality through imagination and representation.

Likewise, cultural anthropologist Victor Turner claimed that the party is a liminoid experience in itself.[6] According to Turner, to enter a party is to enter “into a collective, creative transformation of identity, time and space separated from everyday reality.”[7] This experience opens the possibilities to a parallel world that allows for the subversion of hegemonic social conventions. The relation between music, body, and dance creates a communal experience that allows for exploring multiple alternative models to those socially established.

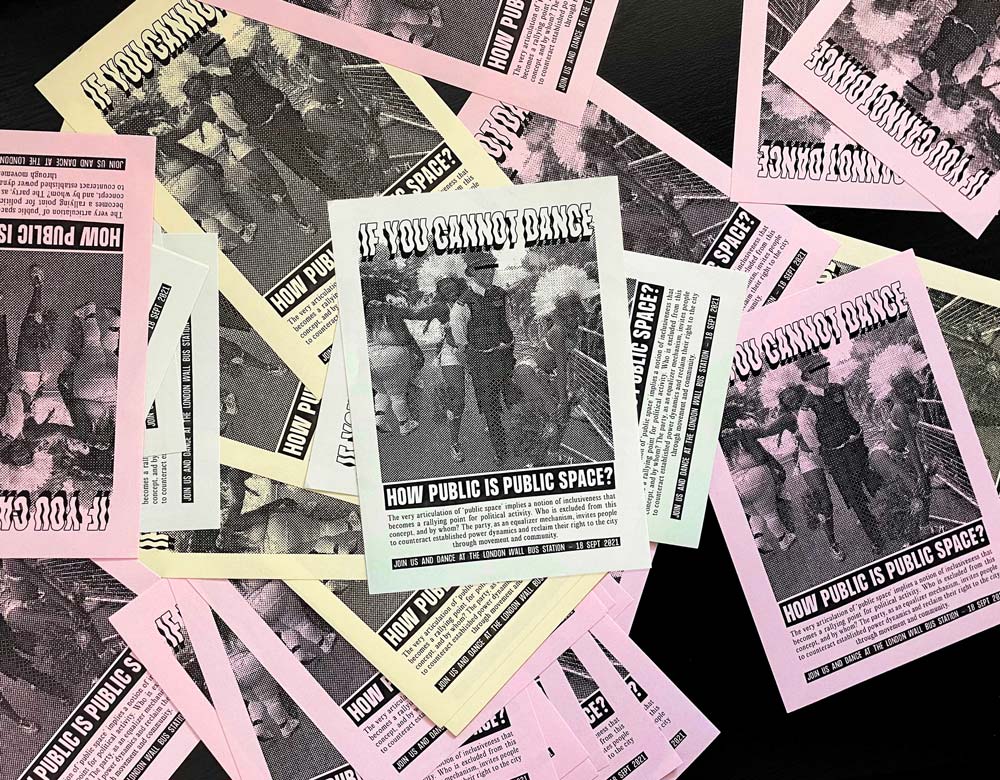

The UK rave movement, heir of an industrial and coal-miner past, created a new nightlife scene in abandoned warehouses and former workspaces. Young people danced tirelessly until dawn where their parents used to work. They appropriated, with frenetic dance moves, former productive spaces and turned them into leisure temples. However, this young community also represented a new form of political dissent against the status quo that contested, through the party, Thatcherite tenets of individualism and societal atomization. This social movement, based on collectivism and inclusion — without overlooking the role that certain drugs played in its development — can only be understood in relation to the dominant neoliberal political ideology. As the movement grew in popularity, so did the tightening of laws and police repression, leading to numerous conflicts and raids. Thus, the scene moved to other public suburban spaces — around the M25 London orbital motorway — and to the countryside, searching for new locations. In response to the rising tide of acid house parties, in 1990, the British government proposed the Entertainments (Increased Penalties) Act, toughening the penalties for unlicensed parties. In light of the situation, more than 8,000 people gathered in Trafalgar Square under the slogan ‘The Freedom to Party.’ Although the UK government passed the bill anyway, dancing — once again — served as a tool for claiming visibility and political agency, for claiming their right to the city.

David Harvey explains in Rebel Cities: From the Right to the City to the Urban Revolution, that Lefebvre brings a new dimension to the Marxist theory, asserting that “revolutionary movements frequently, if not always, take on an urban dimension.”[8] He argues that these movements, rather than being constituted exclusively by factory workers, are formed by urban workers, which have a fundamental role in the construction of cities. Or, as Hardt and Negri claim: “The metropolis as a factory for the production of the common.”[9] Like in the rave scene, the shift from the factory to the city changes the conception of spaces of representation. This social movement based on escapism, with the desire not to be seen in public, appears in the city’s main spaces to claim their rights and inclusion into public life. They took over public spaces to fight for the communal values that they promulgated in their parties through dance.

“By claiming space in public, by creating public spaces, social groups themselves become public.”[10] We understand, therefore, the public space as the third circle of representation.

Rama de Agaete (1960-69) – Extracted from a video property of Odessa Campos, Digitization CCA Gran Canaria.

The Right to Dance: The Party as a Third Place

Between the ’40s and the ’50s, sound systems started to become popular in Jamaica. They consisted of sets of speakers — as big and loud as possible —, a mixing desk and an amplifier. Usually transported in a van-like vehicle, they functioned as mobile clubs that were set up in open areas, turning them into on-the-spot dancehalls. This informal practice became one of the most important cultural manifestations of the island, serving to claim black people’s voices in contrast to the culture imposed by British colonialism. Its components, rather than the specific spatial features of its location, were just music and people.

The direct influence of human activity on the urban environment is discussed in A Pattern Language. Towns, Buildings, Construction (1977), in which Christopher Alexander, with Sara Ishikawa and Murray Silverstein, presents a manual that sets out ‘an urban and architectural pattern language’ for the city. In his breakdown of patterns, Alexander equates physical elements — such as the ‘sewage system’ or the ‘public transportation network’ — to non-physical ones, such as ‘children playing on the street’ or ‘old people everywhere.’[11] In the city, physical spaces are only important as far as people use them.

It becomes evident that the social fabric suffers when its main spatial platform, the city, is forced to limit its use. For Ray Oldenburg, these ‘sociospatial’ relationships are also essential to achieve a desirable spatial quality. He exemplifies this view with the concept of ‘third place.’[12] He emphasizes the need for places that allow for daily activities that reinforce the collectivity outside the office and the home. He claims for spaces that do not cover essential aspects of the home-work-shopping routine, considering ‘necessary’ the ‘non-necessity’, which he calls the ‘informal public life.’ If the home is the ‘first place’ and the office the ‘second place,’ the social being requires ‘third places’; spaces that are not only public but also civic[13].

There is an anthropological component where Oldenburg’s and Alexander’s visions converge: people. Among the characteristics required of a third place to function, the former remarks concepts such as the regulars, the playful mood, being a home away from home, and also — and this is worth emphasizing — being a leveler; a place where everyone, regardless of their socioeconomic characteristics, is on the same level[14]. It is crucial how, even though the title focuses on bars, coffee shops, and bookstores, the features that become more relevant in the conception of a third place are rather social than spatial.

During the ’60s and the ’70s, block parties became popular in the United States among the African-American community. Excluded from the white leisure offer, they started to organize their own festive spaces. Although they are not exclusive to the African-American community, block parties are a paradigmatic example of the appropriation of public space for collective celebration without the interference of administrative or economic powers. The same happens with some of the case studies mentioned above. But even those initially communal and open parties are prone to end up being phagocytized by the established commercial model instead of remaining within the margins of economic operability in which they were conceived: “While club culture still exists today, the strong presence of bouncers, high entrance fees, dress codes, and drink charges have little to do with the original illegal rave scene.”[15] Self-managed celebrations are constantly in jeopardy due to economic, health, and social factors.

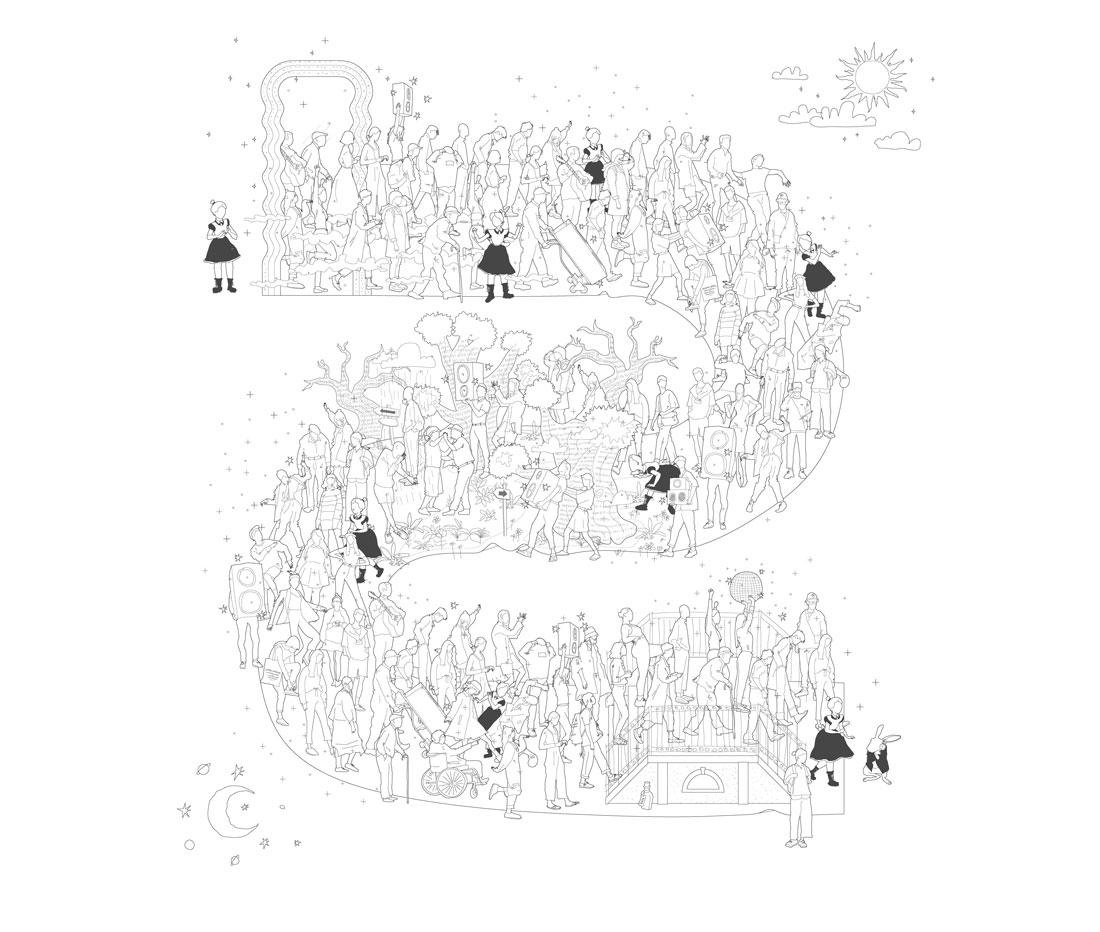

Three Parties in Wonderland and how Alice found the path – Illustration by à la sauvette.

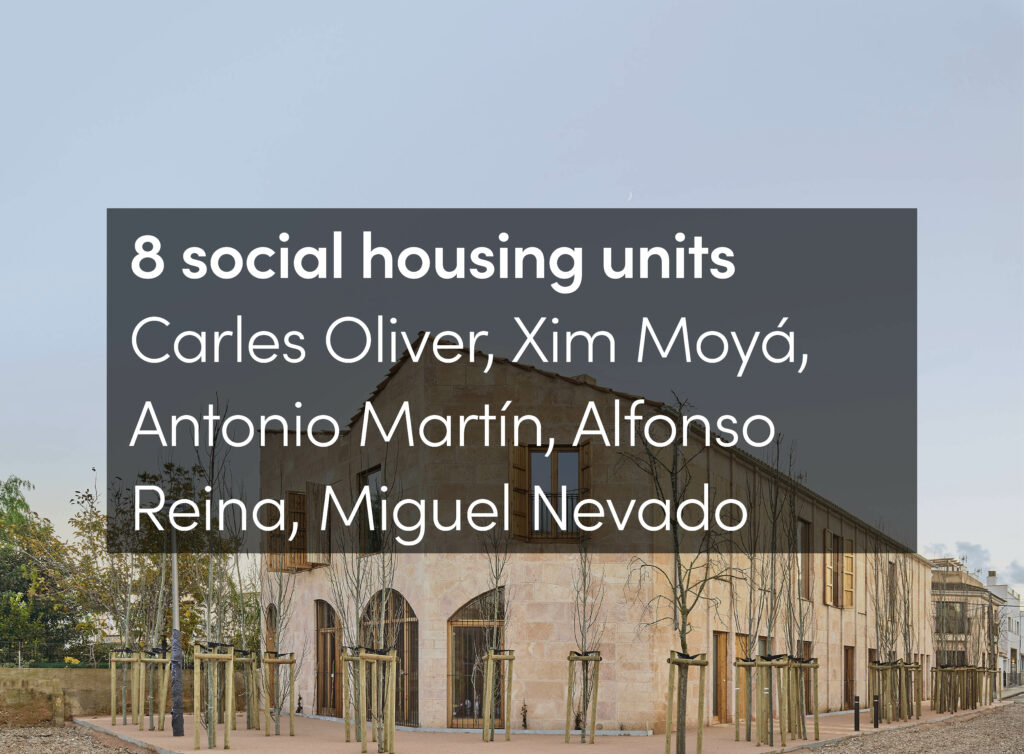

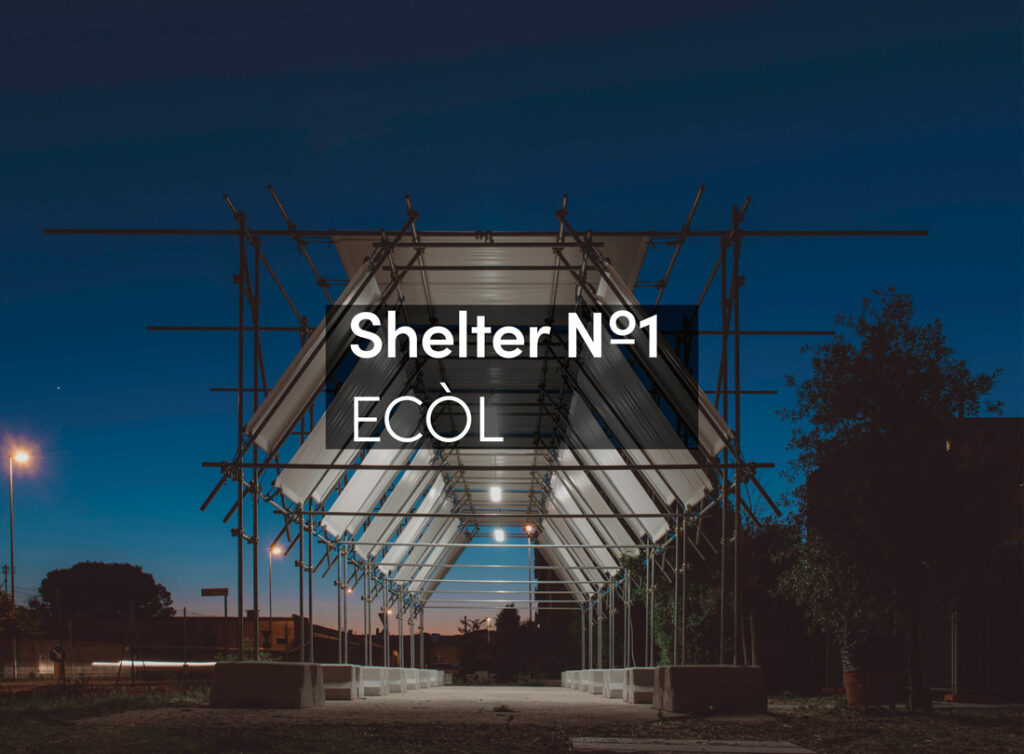

Building Together a Non-stop Dancehall

In the modern global city, and even more so in the digital city of the last few decades, there is a tendency towards urban hyper-productivity. The promotion and implementation of profitable uses and flows confront the notion of a democratic urban fabric that allows for intermediate spaces. There is an urgent need for a city that cares for bodies and their multiple identities, an urban space that accommodates their public expression.

Within the current context, third places are constantly under the threat of becoming subordinated to the will of a private sector whose interests are economic rather than social. Contemporary cities see how their primary ‘public spaces’ become semi-private places that rely only on economic powers to function, which inevitably leads to urban inequality. These spaces are opposed to the very notion of third place. As carnivals are removed from the streets, cafés with terraces, sponsored parties, and motorways with glossy ads grow exponentially.

As we understand it, the party would fit better into the categories of third place enunciated by Oldenburg than the programmatic uses he proposes. Parties or celebrations of any kind are a backbone for identity claim and public representation for communities of different sizes and nature, becoming an essential political tool for visibility and a driving force for social change. Not as a frivolous or naïve gimmick, but being aware of the crucial role of partying and dancing in expressing and reaffirming community identities through collective celebration.

Partying is a political act.