Last December, the Catalan Generalitat passed a law regulating the construction and rental of community housing, known as co-housing. This defines a type of micro-house that allows the interior to be reduced to a minimum of 24m², adding another 12m² (to reach the minimum space standard of 36m²) of shared spaces, which would optimise functional spaces such as laundries, work areas or communal living rooms. This model is based on continuous interaction between users and aims to promote social cohesion.

Recently this type of housing was partially tested in tutored housing for older people or in cooperative housing projects such as La Borda, in the Sants neighbourhood, or the Xarxaire building, which is starting to be built in Barceloneta.

However, the idea of attributing urban qualities to housing using external spaces and co-use of some of its areas has a long history.

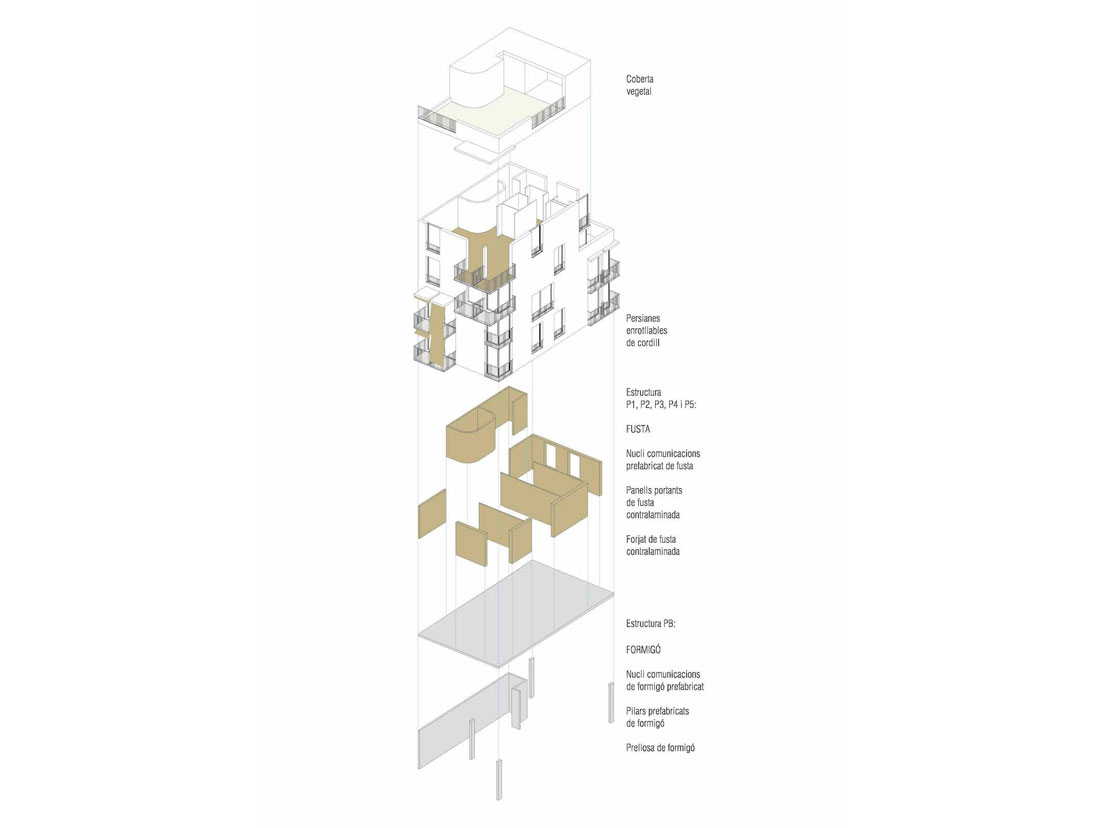

Axonometry of Xarxaire by Mar d’Arquitectes

The Soviet ‘komunalki’

19th century homes in the United States without kitchens were extensively studied by architect Anna Puigjaner. A similar concept was developed in post-revolutionary Soviet komuna houses.

In the USSR, the complicated economic situation at the time, industrial growth accompanied by immigration, and a shortage of housing, led to the development of a series of innovative and sometimes radical types of housing including minimal and community housing. The Komunalki were the first type to be developed, they were collective houses that emerged from sub-dividing bourgeois apartments where several families shared bathrooms and kitchens, with a ratio of 5m²/person.

Apart from reusing bourgeois apartments, urban projects were also created based on the idea of sharing space between several families. The first blocks built in the early 20s consisted of 2 or 3-room dwellings where the floor area was counted separately so that they could be distributed between several families.

This type of rudimentary co-housing formed the basis for extensive and fruitful typological research that generated varied models. The most well-known is the Narkomfin complex in Moscow, built in 1929 by architects Ginzburg and Milinis, for Ministry of Finance employees.

‘Efficient’ housing

This building containing houses of various types was accompanied by a module with a communal kitchen and dining room and spaces for physical activity, while the laundry and maintenance block was never built.

Many of the projects in the 20s and 30s were governed by the spatial efficiency measurement, an economic measurement that quantified the relationship between the constructed volume and the usable area of the housing: the lower the measurement, the more efficient the housing was.

This made clear the need to share functions and design urban residential complexes, such as the Dom Komuna. The construction and distribution of housing in the USSR was linked to workers cooperatives or state-run companies in the same sector. Thus, residential complexes ensured some homogeneity for inhabitants.

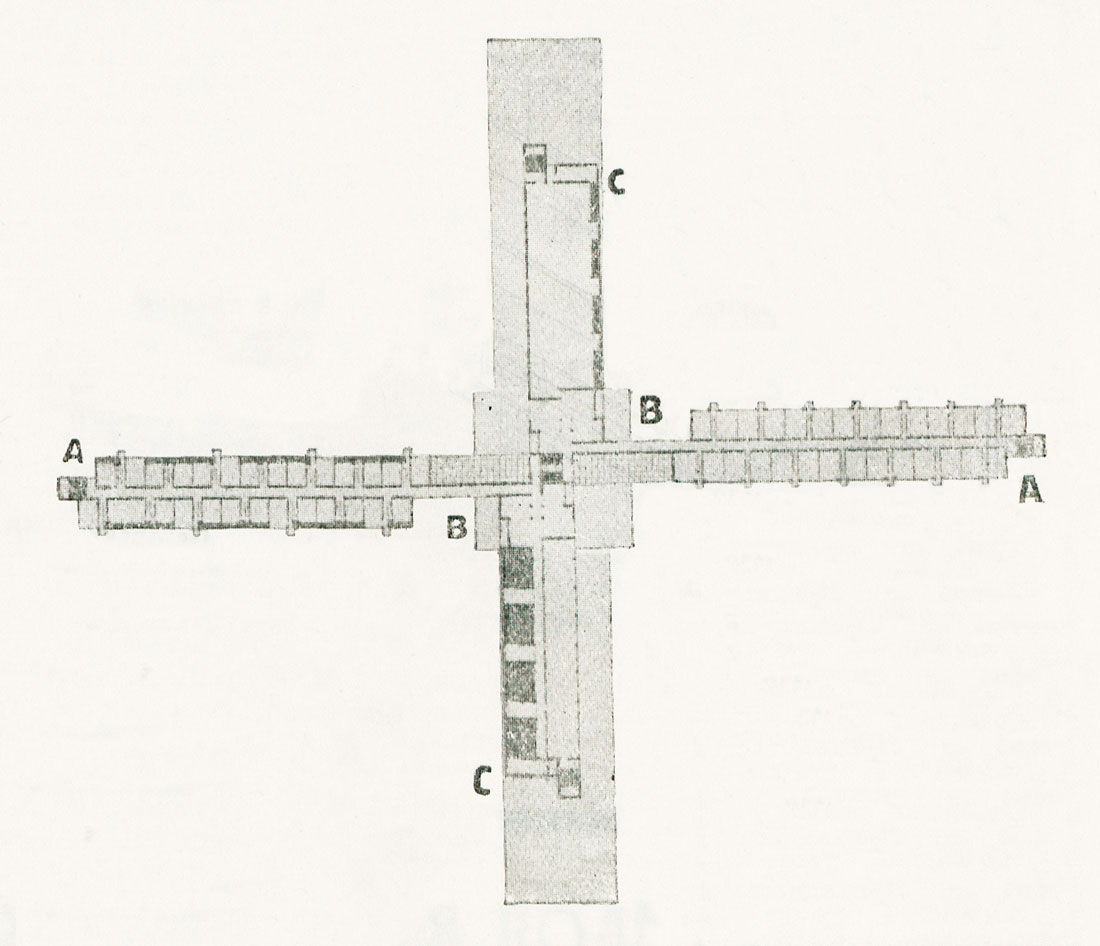

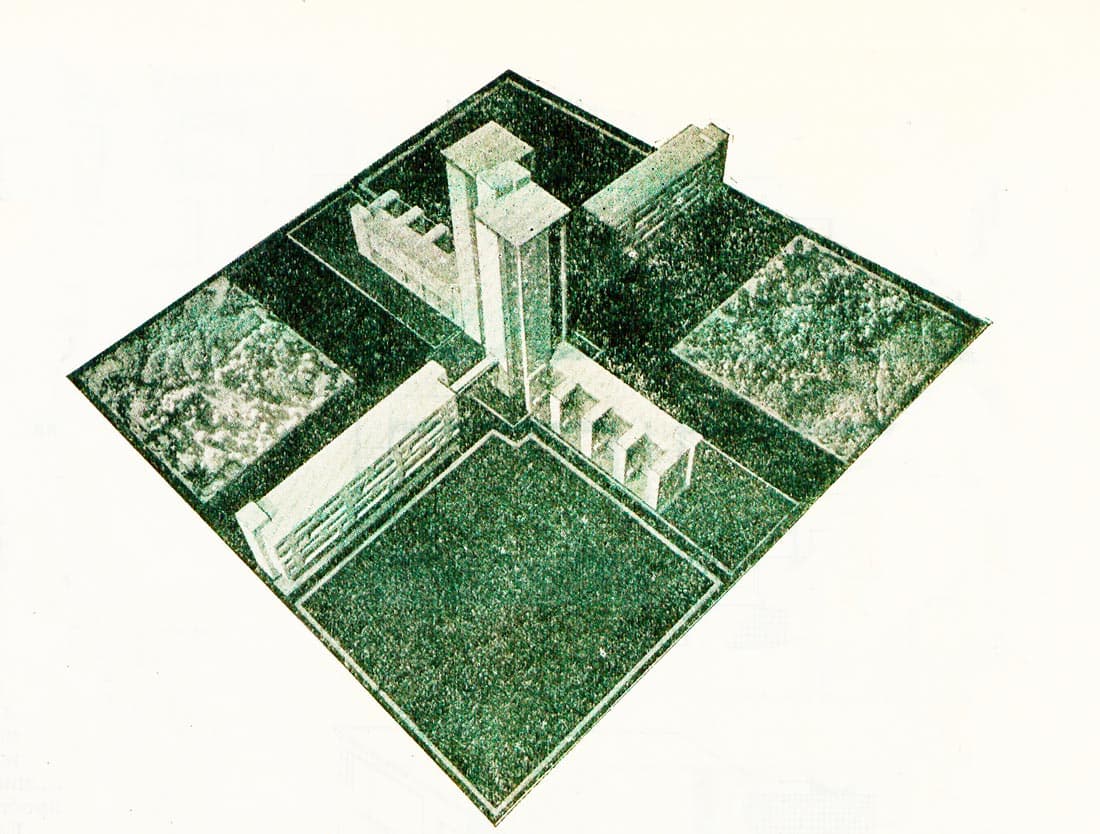

Dom Komuna by Barsch and Vladimirov, published in SA magazine, number 4, Moscow, 1929

Shared spaces

One of the important demands was to meet multiple needs and several projects included educational spaces, nursery schools, physical activity spaces, libraries and reading rooms, as well as communal laundries, kitchens, and dining rooms.

These services enabled most of the domestic work to be externalised and ensured women could participate in professional activities. Apart from the large complexes that were made up of housing blocks of different types with shared functions, there were some projects that went beyond this and bordered on dystopia.

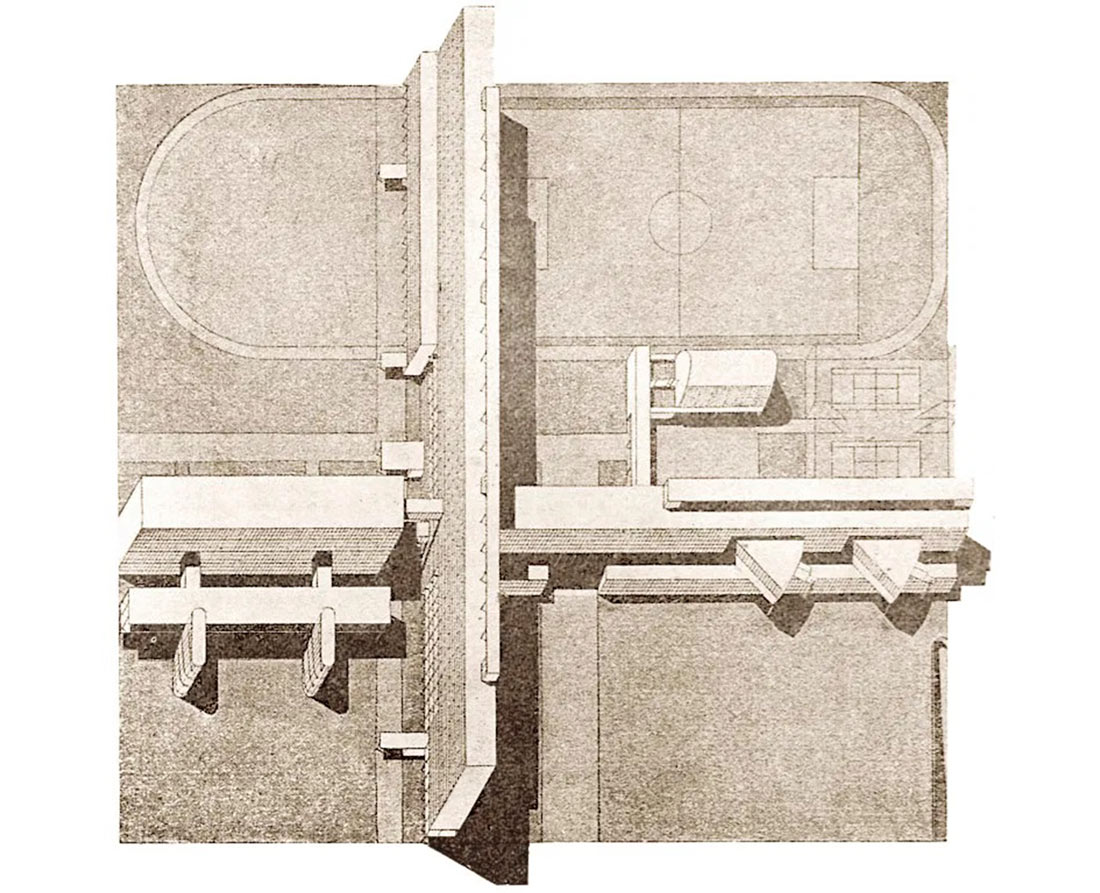

Dom Komuna by Vitaly Lavrov, published in SM magazine, number 7, Moscow, 1929

Failed projects

A project by architect Vitaly Lavrov disaggregated and regrouped traditional housing uses, seemingly more efficiently, into volumes separated depending on the activities and the noise they generated.

The first module contained the sleeping units with single and double units, arranged around a central corridor to optimise the volume. The second extended into individual work areas, which could be allocated and distributed as needed. The third module contained areas for community activities and services: kitchens and dining rooms, nurseries, pre-schools, libraries and reading rooms, sports areas, laundries, maintenance facilities and shops for provisions.

A 1929 project by architects Barsch and Vladimirov was set up based on the hypothesis of the division of the family nucleus according to age and activity. The project consisted of separate modules for adults, children under 8 and children of school age.

Each had adequate spaces for activities: the 10-story adult module contained single and double bedrooms (6m² per person), with modular furniture and bathrooms shared between two units. The lower floors contained individual storage, kitchens, and dining rooms. The children’s modules had rooms with dormitories for 30 students. Younger children slept on the lower floors, close to the gardens, while school children were on the upper floors, with classrooms and workshops occupying the lower floors.

Dom Komuna by Vitaly Lavrov, published in SM magazine, number 7, Moscow, 1929

Out of the many variants of this co-housing from the past very few were built, and none functioned based on a design where the domain of collective life prevailed over the individual.

However, it is worth remembering the work that went into these projects that involved thinking about different solutions and understanding housing at an urban level. They insisted on services and facilities being nearby because of thier importance in terms of optimising residential construction, improving its quality and ensuring equal opportunities for all inhabitants.