While we have achieved unprecedented infrastructural feats, technical developments, and increased prosperity, our urbanity has also created the grandest challenges we have ever faced. The societal successes that enabled our massive urban expansion have simultaneously enabled our intellectual capabilities to recognize these problems. We can now characterize and predict with confidence the very real and dire consequences of unchecked resource consumption and environmental degradation. The urban climate is full of dangerous positive feedback loops that models show are driving conditions to be less and less conducive to life (Meggers et al. 2016; Bruelisauer et al. 2014; Allegrini, Dorer, and Carmeliet 2012; Salata et al. 2016).

But we don’t create solutions by developing models or by disseminating the science and statistics of climate change, urban heat islands, and ecosystem contamination. We must design solutions to these problems. With a significant cohort of people disinterested in scientific reason, our solutions must not simply react to those scientifically defined motivations. They must be creative beacons that enable new paradigms on a tangible level that broadly engages the community. We can combine solutions to perceivable goals like beauty and comfort with those derived more abstractly like climate change (Bruelisauer and Berthold 2015). The surfaces of our urban infrastructure and, more importantly, our urban living ecology must be recognized as an underutilized actor with great potential to affect paradigm changes.

Our understanding of the dynamics of the built environment and its impact and interface with the environment has never been more important. Buildings are constantly trapping heat from the sun, utilizing high value generated energy, and rejecting heat into the environment. Dealing with these dynamics leads buildings to be the largest sector of greenhouse gas emissions, but also implicates them as a major source of the urban heat island. In our work at the CHAOS lab at Princeton, we investigate energy exchanges and explore the thermal interfaces that are directly perceptible to the public they face (Teitelbaum and Meggers 2017). These are clearly mediated through the spaces created by the buildings both inside and out. Although the people living inside a building certainly experience space, the perception of comfort and the thermal condition imbued upon those people has far less to do with space than most consider. Surfaces matter.

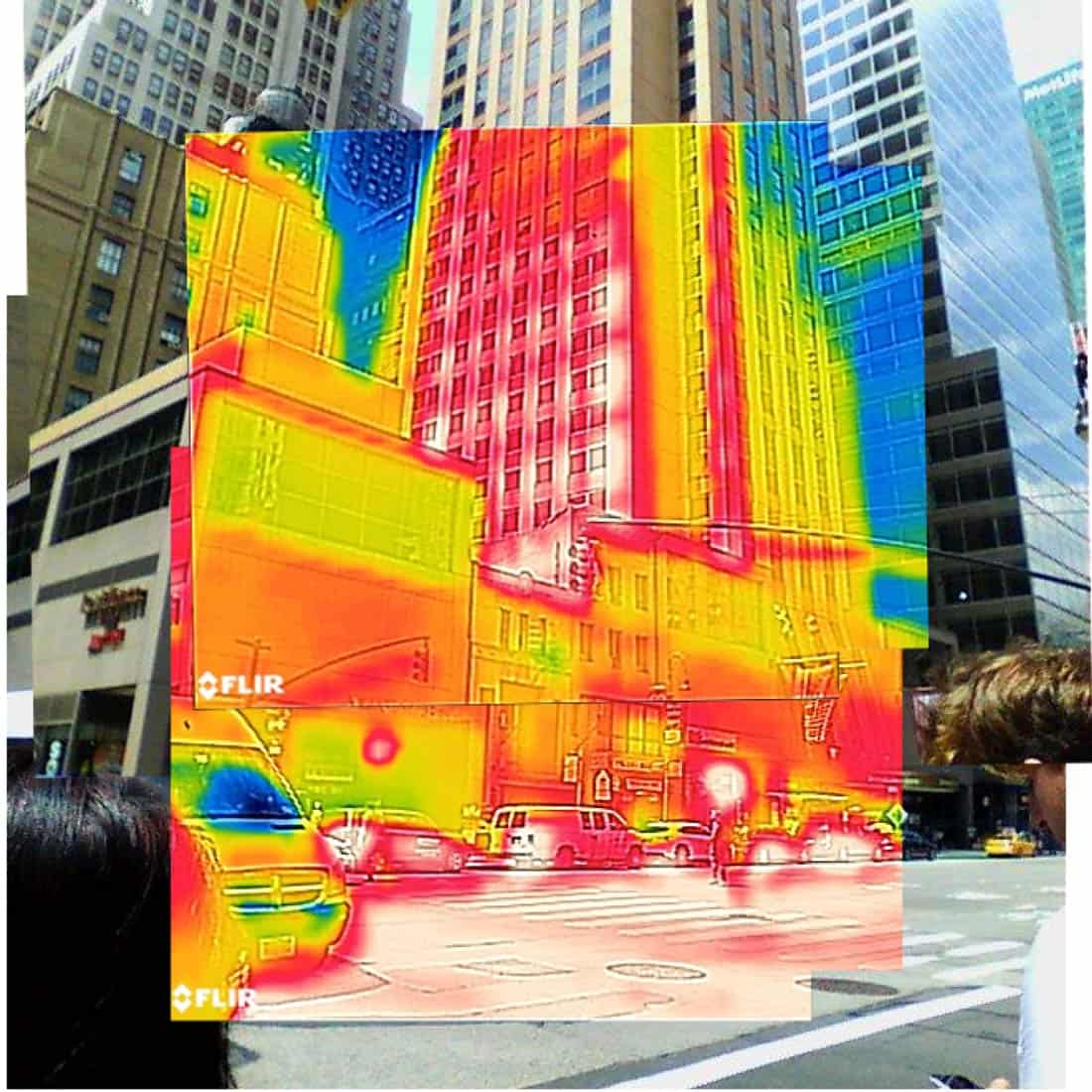

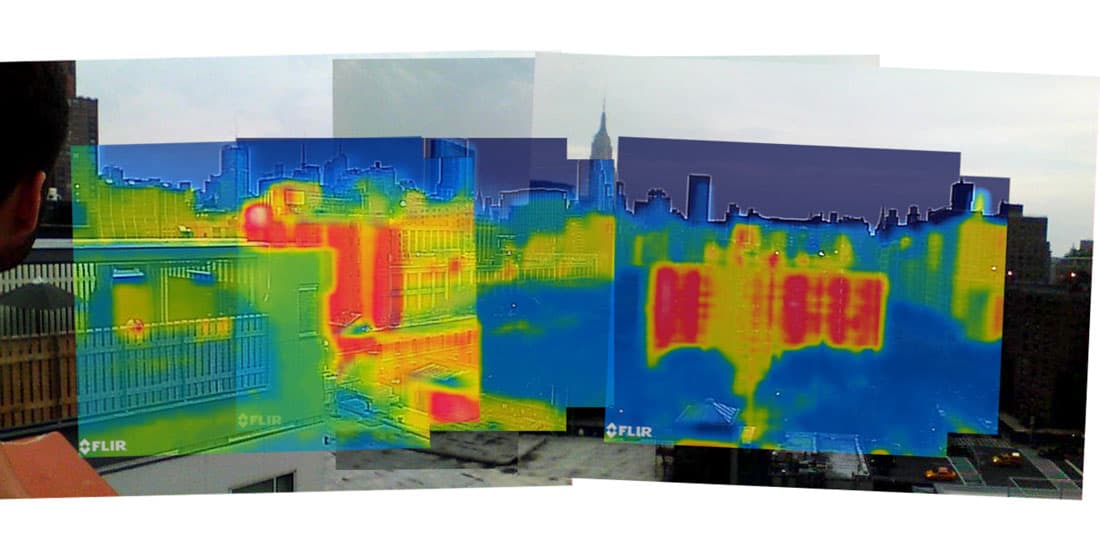

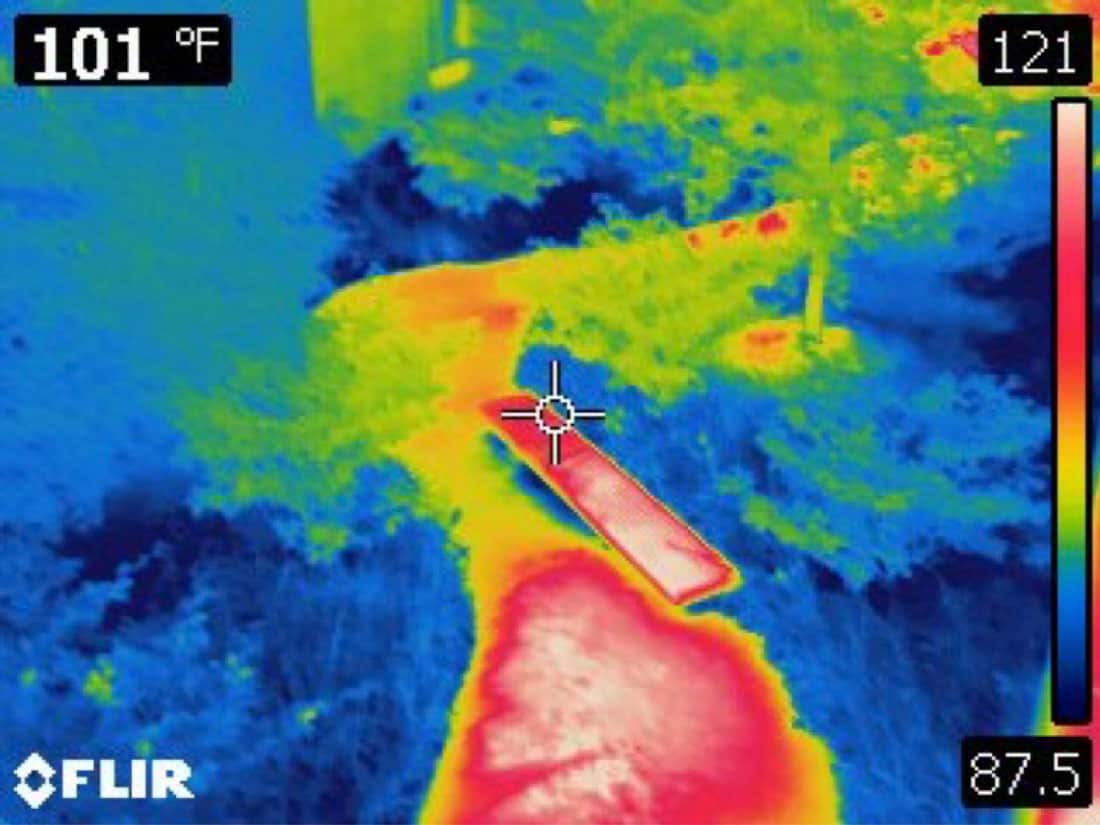

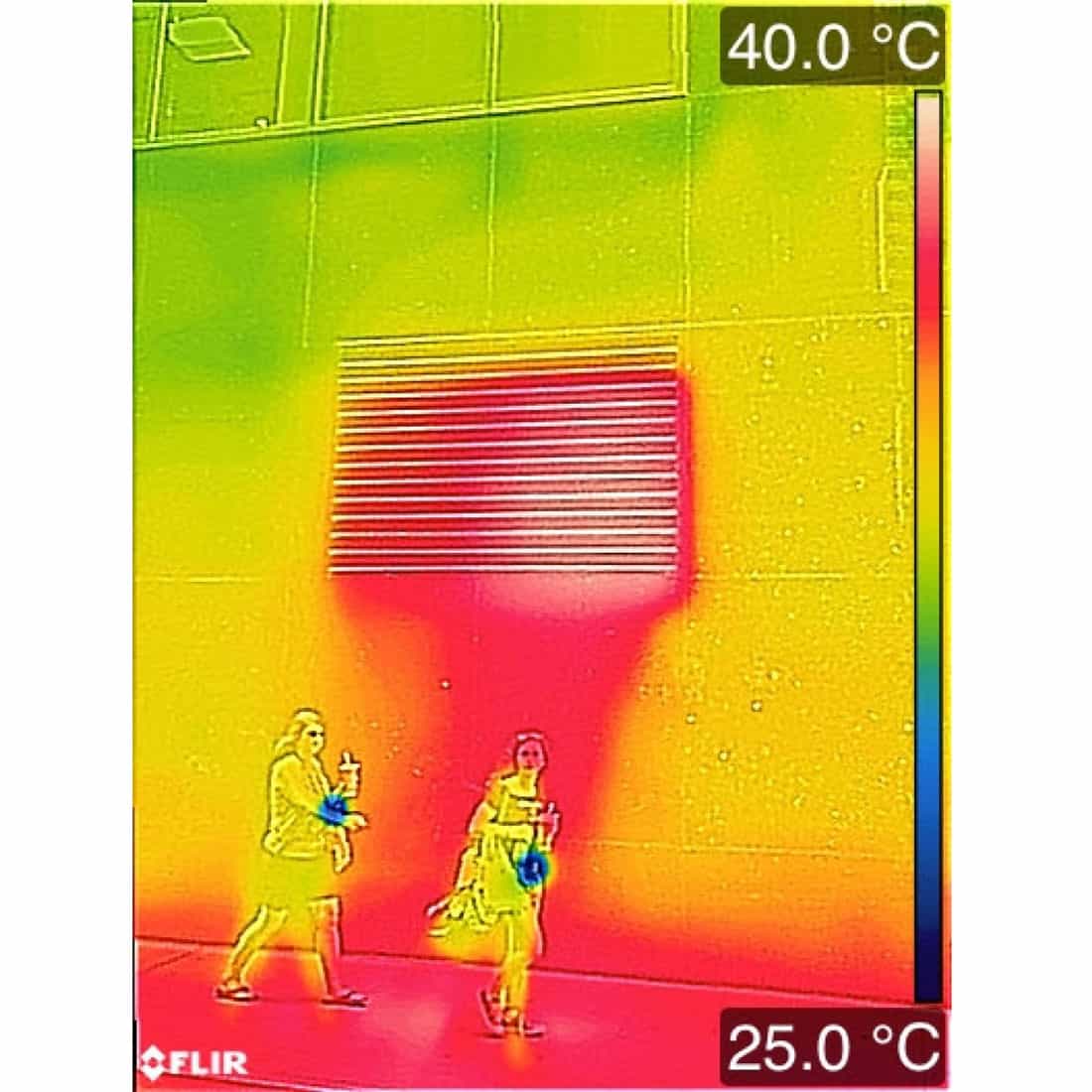

We recognize buildings primarily by their surfaces, yet we believe we aren’t in contact with them without touching them. But building surfaces are actually in constant exchange with their occupants and with the surfaces in and around them. This includes both the dynamic living people inside as well as the ecology surrounding them. Any surface above absolute zero emits radiation in the form of photons—no different than the light we see from the sun—just with a bit less energy. We don’t see these photons in the visible spectrum, but we do experience the thermal energy they exchange. The recent rise in thermal imaging has provided unprecedented visualization of a new world of surface emission rather than surface illumination, and a new ability to design sensation and perception of temperature. The infrared radiation that surfaces emit is a loss of energy and the received radiation is a gain. Therefore, any cool surface will be heated by any surface facing it that is warmer. Three design opportunities thereby emerge, from the scale of the human to buildings and to urban environments:

1) considering the warm human surface and its radiant heat losses to the surroundings as a significant portion

2) considering the ability to activate building surfaces to manipulate thermal environments without requiring massive conditioning of air

3) considering the urban scale exchanges the role cooler ecological systems to mitigate excessive radiation load driving UHI and outdoor heat stress.

Humans perceive thermal comfort as relating to “air conditioning.” In a typical conditioned building, half of the perceived temperature is caused by radiation from surfaces, and not from air temperature. Temperature is in fact misconceived in its role around the sensation of thermal comfort. Comfort is really just the ability of your body to most easily shed the heat released from living. All the processes in your body, from brain activity to digestion to walking, have thermodynamic energy exchanges that result in the generation of entropy and thus heat. This heat keeps your core temperature at a healthy 98.6°F, but to maintain this stasis all kinds of thermal mechanisms are at play in your body, ranging from capillary dilation to sweating and shivering.

Comfort is really the sensation that no extreme measures are being employed to maintain your nominal thermal state. So, while being “cold” is the state of losing too much heat, being “hot” is in fact not about receiving too much heat, but rather an inability to get rid of heat quickly enough. Your surface temperature varies as capillaries dilate and contract, which changes the heat transfer to the air and also the radiant exchanges to surrounding surfaces.

Temperature is again what designers immediately focus on, but the wittedness of skin and the velocity of air movement can have dramatic influences on the rate of heat loss from a person. Thermal delight is invoked by the ability to achieve drastic shifts in heat loss across a wide range of conditions from saunas to ice water. The scale of variation we can achieve just by being hot and sweaty in front of a fan or air conditioning vent is dramatic. The heat loss from the body can increase more than tenfold through evaporation and convection in normal spaces.

These non-linear effects are rarely considered in architecture, and human comfort can be addressed much more effectively in design by considering them. Along with other researchers studying human comfort, we have been developing new sensing methods to better interpret the human termal condition in the built environment (Eric Teitelbaum, Jake Read, and Forrest Meggers 2016; Abraham and Li 2016; Arens and Zhang 2006). Our new sensors can detect and interpret radiant heat exchange, and use distributed wireless networks to monitor air conditions more precisely for aspects like humidity along with temperature. These new technologies will shift the current paradigm of comfort models, from the use of empirically derived conditions for room air, to those that respond to the experience of human bodies interacting with not just the air but also the surfaces around them.

Buildings can be designed to leverage their varying temperatures around occupants as well. Interior surfaces can be activated with hydronic conditioning systems, manipulating their temperatures to vary the heat removal from the occupants in a much more precise manner than the highly turbulent mixing ventilation systems that are typically deployed and require the transport of huge quantities of air, which carries 4000 times less energy per unit volume than water. There is a reason our bodies control thermoregulation through our vascular system and not internal airways. Likewise, buildings can operate more effectively with hydraulic systems, and, like humans, can do more than half of needed thermal exchanges by radiant exchanges, which are much easier to control than air flows. On the exterior, buildings can also learn a lot from living systems. Radiant surfaces can be tuned to absorb and emit radiation strategically to mitigate excess warming of the environment or to leverage passive solar heat. New material science has exposed ways that materials can be engineered to strategically reflect solar heat in visible wavelengths, and to only emit heat in the wavelengths for which the atmosphere is transparent, thereby dumping heat into space and creating free passive cooling (Raman et al. 2014).

At the urban scale, the skyrocketing surface temperatures of our built urban fabric come from our failure to use the latent potential of water systems. As sunlight hits our urban structures it is trapped by the geometric form of the city. The sunlight beams in as a direct ray and is absorbed by our built surfaces, causing their temperatures to quickly rise and subsequently radiate out higher temperature photons than their surroundings. But those photons are not emitted in a beam, instead they are diffusely emitted, and therefore the probability that these higher energy re-emitted photons escape the urban space is low. This causes the radiative trapping effect that drives a large portion of the urban heat island effect.

The urban heat island is often described as having an impact on air temperature, but the radiant emissions from all these very hot surfaces have a much greater impact on the heat transfer to the people in the urban environment than the increase in air temperature of a few degrees. So why does this not happen in deep ecological canyons of our forests? Because plants evaporate water. Evaporating one ounce of water is equivalent to removing the heat equivalent of changing the water temperature by 500 °C. Plants are constantly doing evapotranspiration – pumping water up to their surfaces and evaporating it through their stomata. At Princeton, we have designed and modeled new concepts for making evaporative walls of buildings (Teitelbaum et al. 2015). As part of an NSF Sustainability Research Network called the Urban Water Innovation Network, we have shared those ideas and further explored the dynamics of how access to urban green infrastructure helps mitigate radiant trapping effects, and also can dramatically reduce the heat stress imposed on urban canyon dwellers (Georgescu et al. 2014).

It is not necessary to understand the abstract science that drives these surface mechanisms from the human to building to urban scale in order to invoke the perceptible design interventions they make possible. These interventions can drive a paradigm shift toward acceptance of solutions necessary to address our scientifically characterized grand challenges, without the politics of debating the abstract scientific rationale for doing so.

Good design is implemented because it is accepted as better, not because it is understood as rational. Recognizing the role of human life and ecology as instigators of thermal condition will enable important creative solutions that make people more comfortable in the city by moving away from models that use air temperature as the only meaningful variable in our built environment. This shift will enable architects and designers to engage with surfaces in new thermal ways and, in turn, facilitate meaningful alleviation of the abstract grand challenge of emissions and climate change scenarios with solutions for something everyone can appreciate—being more comfortable.