1. Dialectics of Living and Dead Labor

In “Fragment on Machines,” Marx made the case that with investment in automated technology, which he called fixed capital, capitalism is able to reduce necessary labor time and increase both surplus labor and value. Marx then speaks of the possibility of sublating surplus labor to free time, which he understood as “both idle time and time for higher activity.” This speculation, in which the type of labor corresponding to a capitalist mode of production disappears, is predicated on new technological developments. Within the concept of free time, Marx envisions a communist emancipation of the subject, since free time “[transforms] its possessor into a different subject, [who] then enters into the direct production process as this different subject.” This idea resonates with Marx and Engels’s famous lines in The German Ideology in which they state that within a communist society, it is “possible for me to do one thing today and another tomorrow, to hunt in the morning, fish in the afternoon, rear cattle in the evening, criticize after dinner, just as I have a mind, without ever becoming hunter, fisherman, herdsman or critic.” With this utopian image in mind, however, we should not, as Marx himself emphasized, confuse “free time” with “play” in the sense of Charles Fourier. Instead, free time needs to be understood as productive, as for allowing individual interests and desires to be developed while contributing to societal and scientific progress at large. The will for free time requires its organization against constant valorization, which is to say, alienation. One hundred and sixty years after the Grundrisse was written, Marx’s question of how to effectively sublate surplus labor has yet to be fully resolved. Yet in the recent past, there have been three main responses, which can be summarized as follows:

1) Seize the means of production, such as in various socialist collective projects.

2) Transform surplus labor into a form of resistance and the general intellect into a multitude, as outlined in the work of thinkers like Toni Negri, Paolo Virno, and others.

3) Accelerate towards full automation, implement universal income and an ethic of “working less,” as in the Situationists and, more recently, accelerationists.

The strength, and weakness, of each of these proposals for imagining and realizing a post-labor condition—which are, in all fairness, caricatures of their political nuance—is based on the idea that machines are both utilities and economic categories, or in other words, fixed capital as Marx categorized them. Yet fixed capital is always double: it is both capital for capitalists and tools for workers. As capital, it works with what is in circulation to extract surplus value, and as a tool, it establishes direct psychosomatic relations with and between workers. In order to better grasp what is at stake in the idea of a post-labor condition, we need to inquire into the question of free time again without following Marxian dogma or succumbing to postcapitalist excitation. In other words, the question is not whether full automation will negate capitalism and dialectically result in a postcapitalist society. If we raise the question of post-labor as such, we will fail to take into account the social history of industrialization and will mistakenly consider automation as something that happens only in factories, like Marx’s fixed capital. Instead, we should recognize, as Gilbert Simondon already did nearly sixty years ago, how contemporary capitalist developments make Marx’s original analysis of alienation debatable, and search for new ways forward.

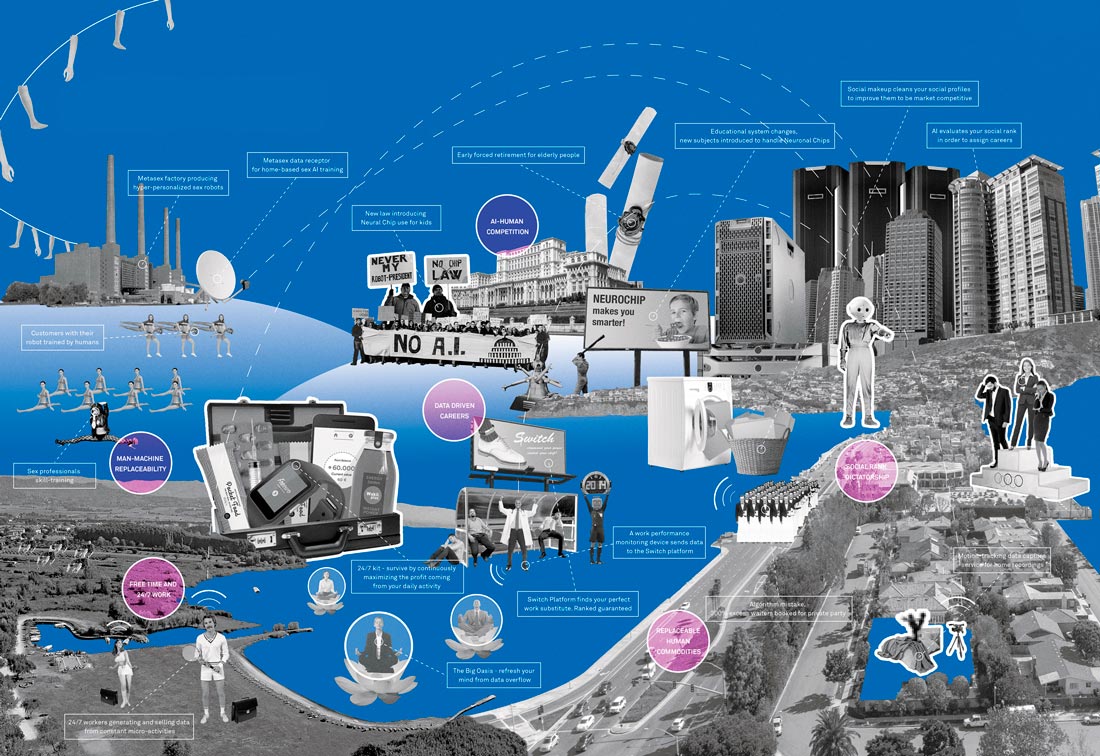

Nefula, The Futures of Work, map, 2017.

2. The Displacement of Fixed Capital

Fixed capital has left the factory and moved into smartphones, homes, and cities. The environmentalization of fixed capital in the name of smartification characterizes an algorithmic governmentality that effectively modulates transindividual relations and valorizes them through quantification, data analysis, and predictive algorithms, all the while establishing and institutionalizing new regimes of truth. Those who “play” on Facebook or its equivalent as if they have plenty of time are not enjoying free time as such but rather entering into a constant process of valorization in which time and experience are exteriorized as data and immediately analyzed to further seduce users into consumption. One could even argue that this social condition of feedback, and the fact that Marx’s dialectical overcoming of surplus labor and necessary labor time is incomplete, is one of the most fundamental characteristics of post-Fordist society. By questioning the notion of fixed capital, we are obliged to enter into a historical analysis of labor and the category of the worker according to the evolution of technology, from “working machines” to steam engines and contemporary cybernetic machines. It is only through such an analysis that we will not only be able to shed new light onto the seemingly dead-end dialectics that Marx put forward in “Fragment on Machines,” but also to identify the source of alienation in the digital epoch.

Marx already pointed out that the development of fixed capital will determine to what degree general social knowledge can become a direct force of production. However, we should notice that although machines are considered a historical category, they are nevertheless only analyzed as an economic one. It is exactly on this point that Simondon criticized Marx: “Under this juridical and economic relation there is a more profound and more essential relation, which is the continuity between human individual and technical individual, or the discontinuity between these two beings.” By “technical individual,” Simondon means technical objects which have attained a certain level of autonomy based on recurrent causality or feedback. Besides the psychosocial necessities of being human, there is also, according to Simondon, a psychosocial character to technical objects, which is not so much an animism as it is a reciprocal and collaborative relation between human and machine. Before the Industrial Revolution, artisans were capable of creating an associated milieu when working with tools in their ateliers, in the sense that they themselves had the status of technical individuals. In the condition of labor Marx describes, artisans and peasants are forced to leave their ateliers and work in the factory. These workers—which Simondon calls “laborers of elements”—don’t understand machines as technical individuals, as they are used to the artisanal way of working with tools, that is, taming them. Changing the gestures they developed in their previous experiences demands also a change in mentality, since now machines instead of the workers are technical individuals. When these artisans work with machines, they are merely users, repeating their gestures according to the predefined operational procedures and the rhythms of the machine, which gives rise to an existential malaise. At the same time, capital sees technical objects as mere means to improve production efficiency and increase profits, without paying attention to the sociopsychological relation between human and machine.

Simondon claims that labor is only a phase of technicity, and not vice versa. If artisanal labor is conditioned by the technicality of the tools, then new, industrial technologies produce a new form of labor. As Simondon pointed out, in the transition from artisanal labor to industrial labor, there was no change in the polarity of technical knowledge, namely the division between technicians who are conscious of technology and reflect upon it (like adults) and ordinary people concerned only with use (like children). In other words, there are technicians who are responsible for repairing machines, while workers, as just ordinary users, do not necessarily have the technical knowledge to take care of machines, to extend the lives of machines beyond the moments of their creation and production and use them in support of the laborer’s own individuation. Individuation here, to risk simplifying it, means the worker’s capacity to benefit from their work beyond economic means in sublimated form, namely either as repression or elevation, conscious or unconscious. For Simondon, the inability of the worker to adopt machines as a condition of work, in the sense of œuvrer, and not simply labor, leads to a double alienation: of both machines and workers, where machines are treated as slaves and humans are turned into alienated labor. In a course titled “Social Psychology of Technicity” that Simondon gave between 1960–61, he further pointed out that alienation is intensified with consumerism, since technical objects now become mere commercial products, like slaves in Roman times, waiting on the market for their future owners to pick them up.

Simondon considers alienation to originate from a more fundamental level than Marx’s economic analysis: not in the ownership of the means of production but in the misunderstanding and ignorance of technology itself. Simondon understands technical knowledge to be an autonomous, or at least only contingently related, epistemological category to that of capital and labor, and suggests its development to resolve the problem of alienation. What Simondon proposes is that it is necessary to understand the schema within technical objects—the way they are organized—in order to revitalize relations between humans and machines and their evolution, and to situate such evolution within a broader reality. This idea serves as the point of departure for Simondon’s critique in his supplementary doctoral thesis, On the Mode of Existence of Technical Objects, that philosophy should work to resolve the problem of alienation by taking the mode of existence of technical objects seriously. In comparison, today, the general public is less concerned with working conditions in factories (except, perhaps, in factories like Foxconn) than with the possibility that automatons will replace humans and that full automation will lead to full unemployment. Yet, does this understanding of what a post-labor condition might look like really mean that we can separate the machine world, in which automatons work 24/7, and the human world, in which humans are progressively detaching themselves from labor processes? Or is there a “base” (e.g., the human-machine relation) that is more fundamental than the “superstructure” (capital-labor relation), and which has to be further questioned?

3. The Transindividuality of Machines

If we follow Simondon’s idea that labor is a phase of the genesis of technicity (and not the other way around) and that the category of “technical activities” extends far beyond the category of labor, we should understand post-labor to be a new technological condition, which suggests a new form of labor taking shape. To understand the post-labor condition and respond to such a new industrial program thus demands a systemic study of the question of technical knowledge today. In other words, inquiring into the formation and distribution of technical knowledge (savoir technique) would work to update Simondon’s theory of double alienation as we move towards a post-labor condition. Yet the technical knowledge and activities we are talking about here cannot be reduced to engineering principles or simply knowing how to repair machines. We must avoid the misunderstanding that everyone has to become an engineer or hacker in order to deal with the problems produced by capitalism. Instead, we should think in terms of the means to reappropriate technology beyond industrial, consumerist applications. Marx hints at this when he comments on the weaving machine in Das Kapital: “This machine … only in some determined conditions … becomes capital.” But this comment demands a deeper interpretation. Reappropriation has to be distinguished from repurposing. Facebook can be repurposed to initiate an anti-Facebook movement, but by doing so, we still commit ourselves to the ontological and epistemological presuppositions of Facebook—for example, how it defines an individual and social relations. How else do we know what social relations are, or can be? Facebook is an application of internet technology, but Facebook is itself not technology per se, which consists of network protocols, programming languages, API libraries, etc. To reappropriate this would mean to create alternatives based on different ontologies and epistemologies, which is far beyond the scope of libertarian hackers.

Bernard Stiegler, interpreting the work of Gilbert Simondon, proposes to politicize the question of individuation against the backdrop of industrialization and consumerism. However, in contrast to Simondon’s Jungian reading of the concept of individuation, Stiegler uses Freud’s theory of desire to understand individuation as a constant libidinal investment, and to interrogate the conditions under which such individuation can take place. Simondon uses the metaphor of crystallization to characterize the proto-process of individuation, in which a supersaturated liquid starts crystalizing when certain material, energetic, and informational conditions are met. In Stiegler’s model, consumerism has short-circuited the mechanisms of individuation, replacing libido with drive and investment with addiction, which leads to a “disindividuation.” Libidinal investment thus becomes the motivation for individuation qua crystallization. In Simondon’s theory of psychic and collective individuation, the role of technology is almost invisible, while for Stiegler, it is necessary to take into account the role of technology in the process of individuation and as a means to bridge Simondon’s two doctoral theses, one on individuation and the other on the individualization of technical objects. If we follow this logic, it means that we need to develop a new understanding of fixed capital in relation to individuation, which will lead us to a new interpretation of Simondon’s critique of Marx.

An understanding of fixed capital can thus be extended beyond that of a substantial being and towards sets of transindividual relations organized according to specific operational schemes. This proposal gestures towards a rejection of hylomorphic thinking—the determination of form over matter, or ideology over power—and suggests that we should think of individuation as a process that takes place both through and with machines. Étienne Balibar first employed Simondon’s term “transindividual” in his Philosophy of Marx to describe the human as an ensemble of relations rather than as closed in on itself like a monad. Yet far richer than Balibar’s very brief discussion of the term, Simondon sees transindividual relations as the very condition for the individuation of psychic and social beings. The psychic being is always already transindividual, therefore it is not possible to separate the psychic from the collective as two substances, which is often the mistake of pure psychology or sociology. Simondon takes Nietzsche’s Zarathustra as an example to illustrate this, and to show that transindividuation can occur even in solitude. Simondon says that “the test (épreuve) of transindividuality starts” when Zarathustra alone carries on his shoulders the cadaver of the loop dancer abandoned by the crowd to bury it.

Simondon’s notion of transindividual relations is not limited to psychical beings, but extends to technical objects. As he writes: “The technical object understood according to its essence, that is to say the technical object insofar as it is invented, thought, and wanted, assumed by a human subject, becomes the support and the symbol of this relation that we would name transindividual.” Simondon therefore endows technical objects with the role of facilitating the process of individuation: “Through the intermediary of technical objects an interhuman relation is created. This is the model of transindividuality.”

The relation to technical objects cannot become adequate individual by individual, except in some very rare and isolated cases; [the relation] can only be instituted under the condition that it succeeds in bringing this collective inter-individual reality into existence, which we call transindividual, because it creates a coupling between the inventive and organizing capacities of multiple subjects.

If we follow what Simondon has said concerning transindividual relations, it opens a new investigation into the role of machines in psychic and collective individuation. This is also a proposal to go beyond the typical Marxian analysis of machines—to reconceptualize them beyond being considered as fixed capital and utility. Transindividual relations are embedded in technical objects and modulated according to their operational and organizational schemes. The evolution of technical objects thus constantly shifts the theater of individuation by reconstructing the stage with new forms of transindividual relations and new dynamics. With its notion of feedback and information, cybernetics introduced a new cognitive scheme, and consequently a new organization of human-machine relations and sociality at large. Simondon relates his interpretation of technical lineage, from “elements” to “individuals” and “ensembles,” to specific historical epochs. He explains that technical elements represent the optimism of the eighteenth century, which longed for infinite progress and the constant amelioration of human life; technical individuals, which appeared in the nineteenth century as automated machines in factories, displaced human beings from the center of production; and in the twentieth century, Simondon saw technical ensembles, with the emergence of information machines and cybernetics, as a new, historically incomplete project of organizing transindividual relations. While Simondon’s discourse on technical ensembles has to be critically evaluated in regard to network culture, which only began to develop after the philosopher’s death in 1989, Simondon’s insistence on understanding machines beyond an economic category (i.e., fixed capital) remains invaluable and perhaps even more urgent today than ever.

4. “Google as General Intellect”

With the advent of social media, the internet of things, and all sorts of smartification supported by various forms of networks, we are witnessing the emergence and concretization of new organizational forms of transindividual relations. The post-labor condition is not the end of labor, but rather a new technological condition within which the notion of work, technical knowledge, and transindividual relations have to be rethought and reevaluated. While we are far from providing a solution to the gigantic problems we face today, it is essential to understand post-labor not simply in terms of a redistribution of resources (e.g., universal income)—which is how Saint Simonians once understood socialism—but rather as a historically situated relation between technology and labor. It is only then that we may be able to overcome new forms of valorization and alienation brought about by such a technological condition.

To understand the problems we face today, it is necessary to analyze the transindividual relations that are embedded within technological developments of cognitive valorization, such as social media, and go beyond an economic or humanist critique to one grounded on the critique of individuation. However, it is important to develop such a critique according to a historical and materialist analysis of categories such as labor, knowledge, social relations. Therefore one must also be cautious when using words such as “immaterial” to characterize the post-labor mode of production. In his A Grammar of the Multitude, Italian theorist Paolo Virno plausibly suggests that we understand the general intellect as a “dematerialized” mode of exploitation. According to Virno, if money is considered to be a “real abstraction,” it is because the material existence of money is realized as the “universal equivalent,” while the general intellect—which consists of cognitive activities such as language, communication, and self-reflection—does not need to go through the process of real abstraction. Virno successfully demonstrates that if, in the capitalist mode of production described by Marx in the Grundrisse, workers were the intermediary between nature and machine, in the current mode of production the general intellect has become directly subsumed. As Virno puts it: “With the term general intellect Marx indicates the stage in which certain realities (for instance, a coin) no longer have the value and validity of a thought, but rather it is our thoughts, as such, that immediately acquire the value of material facts.”

The general intellect for Virno could be understood as the “common,” but also as Simondon’s “pre-individual” reality, or more precisely what Anaximander calls apeiron. As both Stiegler and Jason Read have emphasized, one shouldn’t confuse the pre-individual with mere nature, but rather understand it as part and product of culture and history. Calling it immaterial or returning to “mere nature” risks missing an important step in understanding our contemporary, or post-labor, condition to come. If the general intellect is exploitable, it is only because the environmentalization of machines equipped with the capacity to collect, parse, and analyze data creates a feedback loop that integrates the individual into technological systems. We can thus understand the double meaning of the German word for “general intellect,” allgemeiner Verstand, that Marx first used: on the one hand, it is the understanding (Verstand), the analytic faculty responsible for cognition and recognition; on the other, it is a generalized or transcendental schema which forces itself onto the whole of society, like how Google has made machine categories indispensable for comprehending the contemporary. In other words, the immaterial is the new material.

Virno seems to furthermore separate psychic and collective individuation into two stages, with the “collective of the multitude, seen as ulterior or second degree.” However, as we have seen before, there is no separation between the psychic and the collective in Simondon’s theory of individuation, and indeed they are inseparable. The separation between the two allows Virno to advance an opposition between the individual and the multitude, but he fails to account for how the dynamic of individual and collective individuation is mediated by technical objects. Virno’s move could be understood in the same way that he criticized Marx for “completely [identifying] the general intellect (or, knowledge as the principle productive force) with fixed capital, thus neglecting the instance when that same general intellect manifests itself on the contrary as living labor.” But if Virno’s politics of the multitude can be found in the exploited general intellect, its potential for resistance does not rely solely on “living labor” or a theory of “subjectivity,” but rather demands historically recontextualizing technical objects and repositioning them in an understanding of the process of psychic and collective individuation.

To briefly conclude, if we assume that there is a merging of work and free time in the biopolitics of post-Fordist capitalism, it is impossible to bypass the question of machines, since the operational and organizational schemes of platforms largely determine transindividual relations today. The post-labor condition should be understood not simply from a dialectical point of view, but rather from the point of view of a close examination of technical knowledge and technical activities upon which its new form of labor is built. It is not as if resistance is or will be no longer needed; but we should understand resistance differently, as the transformation of transindividual relations as they are materialized through machines. While this might deviate from what Simondon originally means by the term, we can formulate this as the urgency of “technical knowledge.” Cathy O’Neil, a data scientist and author of Weapons of Math Destruction: How Big Data Increases Inequality and Threatens Democracy, recently urged disciplines such as philosophy, the humanities, and the social sciences to leave their “ivory towers” and engage with algorithms. Although O’Neil ignorantly dismisses disciplines such as media studies, science and technology studies, digital humanities, and philosophy of technology, which have dedicated themselves to these questions for decades, she is right to point out the fact that in the midst of tremendous technological development (and sixty years after Simondon’s analysis), the polarity between experts and users seems to have only enlarged, while technical knowledge largely continues to be treated as antithetical to other, more “pure” forms of knowledge. We need a new conceptualization and politics of the becoming of technical knowledge. It is clear that “technical knowledge” is no longer that of engineering or of highly technical skills (though their importance cannot be ignored). Technical knowledge must transcend fickle epistemic divides and be reinvented beyond dated oppositions between engineering and the humanities, efficiency and reflexivity, positivism and hermeneutics, or even dead and living labor. Only then will we be able to further interpret what Marx originally called “free time.”