“The closed world includes not just the sealed, claustrophobic spaces metaphorically marking its closure, but the entire surrounding field in which the drama takes place.”[1] – Paul Edwards, 1996

Architects have described spaceport facilities as empty industrial boxes in the American landscape.[2] These are not dull boxes but represent the federal government’s attempt to generate architectural modernity, as space programs relied heavily on strategies for enclosing scientific activities, coordinating logistics, and simulating extraterrestrial environments. Particularly in the postwar era, humanity became obsessed with generating a fully “closed” and synthetically constructed “world in a machine.”[3] The spaceport complex was no different. Traditional practices and our understanding of “landscape” are completely detached when intellectually and critically exploring the evolution of the spaceport complex. Instead, the enclosure of the rocket assembly in the American spaceport demonstrates radical changes and blurry associations between technology and land—from the romantic wilderness (or manicured English gardens) to a series of technical lands exemplifying global power. Assembly, manufacturing, and distribution of rockets all contribute to the enclosure of the space program. Curiously, such activities relied on the construction of the garden—the place of natural history tied to technological power—as transformed from the wilderness “out there” to a garden enclosed in the machine. And therefore, the notion of landscape and garden are defined and appropriated into an image of a nation in Cold War politics.

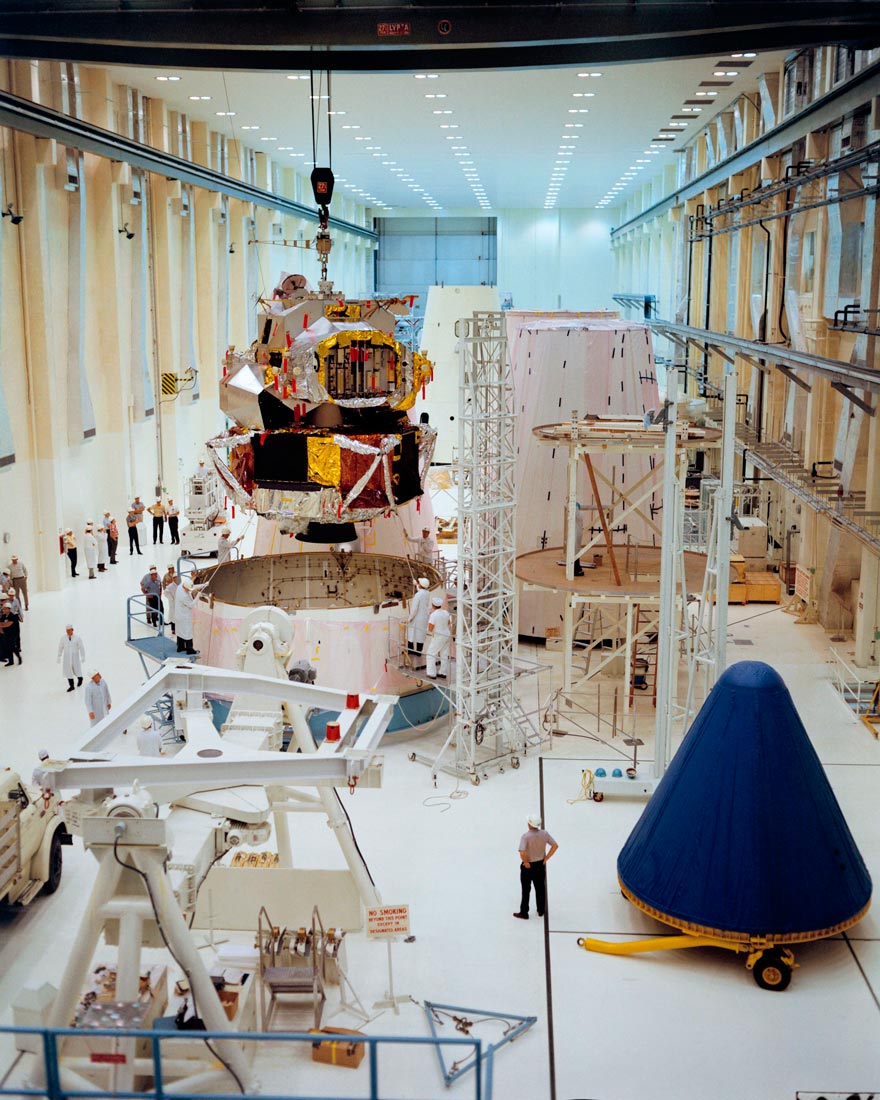

Lunar Module suspended inside Operations & Checkout Building, Kennedy Space Center, 1967, Merritt Island, Florida, USA, NASA Archives

Contrary to David Nye, who suggests the technological sublime came from publicly valued places, architecture, and technologies, architectural enclosures supported the political imagination of aerospace outside of the general public’s view.[4] Shelters in the spaceport emerge in two forms: a shed for assembly production and a blockhouse for rocket launch operation and control. If we view architectural enclosures in parallel with development in rocket technology, architecture’s role directly aligns with an infrastructure of assembly in a network of technical systems for space travel. No longer do we only find a romance of The Machine in the Garden.[5] Instead, a technological elegance for extraterrestrial desire produced isolated enclosures separate from nature and redefined the garden entirely.

By the 20th-century the garden was transformed into a technologically occupied space. It was the traditional European garden—an exterior curation of natural vegetation—that was used to demonstrate wealth, intelligence, and power. Thomas Hughes’ description of the American industrial scenes serves as a rich depiction of the production complex.[6] But in the age of postwar modern machines and with the Cold War conflict in full swing, the garden—previously understood as a manicured exhibition of plants to showcase power—became enclosed and replaced with the synthetic environment for demonstrating technology and science to further construct nature, not necessarily replacing it. The spaceport became the space of national enclosure—both for secrecy and later, coincidentally, for the exhibition of technological knowledge and economic power, including increased control of physical nature.

In 1962 Burn and Roe, architects from New York, were commissioned to design the Launch Operations Center (now Kennedy Space Center) Operations and Checkout Building. In collaboration with the US Army Engineer District of Jacksonville, Florida, the building was designed with repeated “bays” and a series of modest precast concrete panels and exterior columns—not uncommon amongst modern architects. Two masses, approximately 500 feet in length, were designed: one for administrative and engineering offices and the other for the “high bay” used in assembly processes. The building’s primary entrance is located along the long administrative side, with all service entrances on the ends of the assembly area. The administrative portion of the building includes three floors of offices, a flat roof, and horizontally wrapped ribbon windows. Although the windows lack full-length ribbon window frames, the architects managed to express a continuous horizontal band with exposed concrete columns on its exterior—all well-known features from the more recognizable modern architecture of the era.

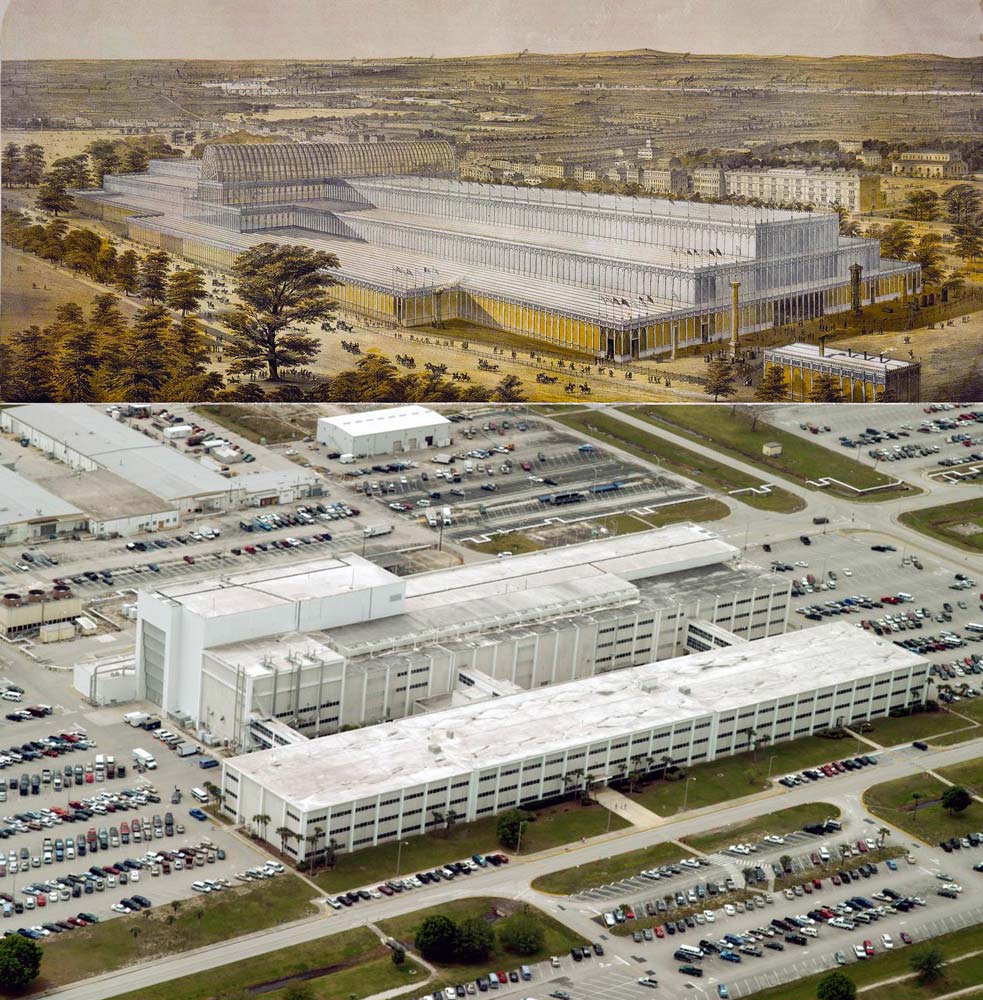

Crystal Palace, Joseph Paxton, 1851, London, England and Operations & Checkout Building, Kennedy Space Center, Merritt Island, Florida, USA, NASA Archives

Crystal Palace, Joseph Paxton, 1851, London, England and Operations & Checkout Building, Kennedy Space Center, Merritt Island, Florida, USA, NASA Archives

Assembly, manufacturing, and operations took place in the second mass sitting behind the first. Structured to enclose a greater volume over 100 feet (approximately five stories in height), this high bay was treated similarly to the cleanroom in Hangar S, only much larger in scale, with integrated structures for gantry cranes and overhead girders. Architects were designing the ultimate clean room for machines as an infrastructure of assembly—indoors. Located on each short end, 100-foot vertical lift doors provide access to all services.

On the original construction documents dated November 2, 1962, the large masses were connected with an additional two-story space indicated as the “cafeteria-conference room and auditorium area.” This is important to note for several reasons. First, the Operations and Checkout building never had such spaces included upon its construction. That the cafeteria, conference room, and gathering spaces for events would occur within the same building as Operations and Checkout suggests that each building in the spaceport offers a variety of programs—in this case, blending machine and human assembly. And secondly, although proposed in the architect’s early drawings, the space between the two masses was later abandoned and used for exterior services, leaving a large space between the administrative offices and assembly. NASA appears to be quickly moving away from individualized, duplicated, anonymous, and repeatable models as we have seen with the military aircraft hangars, toward a completely enclosed complex stretched across a forgotten landscape. And so, it is no surprise that in the later version of Operations and Checkout the cafeteria, auditorium, and common meeting space have been removed from the plans.

Even though the Operations and Checkout building was contracted, designed, and constructed under the same commission, it was ultimately divided into two separate buildings altogether. The decision by NASA administrators to separate the administration and engineering offices from the assembly process is an important indication of the way activities were perceived and rationalized at the much larger scale of the Kennedy Space Center complex as a whole. It is not the spaceport’s Operations and Checkout Building itself that provides a rich architectural history—at least not with public perception—until a value is placed upon its aesthetic image by referencing its important historical associations.

The building design certainly embraces an architectural aesthetic through its seemingly logical expressions with the industrial processes necessary for building modern spacecraft and satellites. As the assembly and office masses were constructed separately, architects later added an elevated and enclosed catwalk bridging over the exterior service area—not too dissimilar to the connections made during the additions of Hangar S to eliminate the need for exterior circulation between mission preparation and procedures. And it is this catwalk which, ironically, became the most distinctive feature in the building’s contribution to America’s aerospace history.

In 1964, when construction on the Operations and Checkout Building was completed, all astronaut living quarters and checkout processes were transferred from Hangar S to the new facility. The astronaut crew quarters, however, were not placed in the administrative mass. Instead, they were located within the larger assembly building—the same facility where their Lunar Excursion Module (LEM) was being assembled in preparation for transporting the crew from the Apollo command and service module (CSM) to the surface of the moon. The Operations and Checkout Building illustrates how an increase of enclosed environments began well before opening the capsule hatch atop the massive Saturn V rocket. In other words, the entire spaceport complex, including its assembly facilities, contributes to its disassociation with the natural environment and completely constructs its enclosed world—moving from one enclosed space to another.[7]

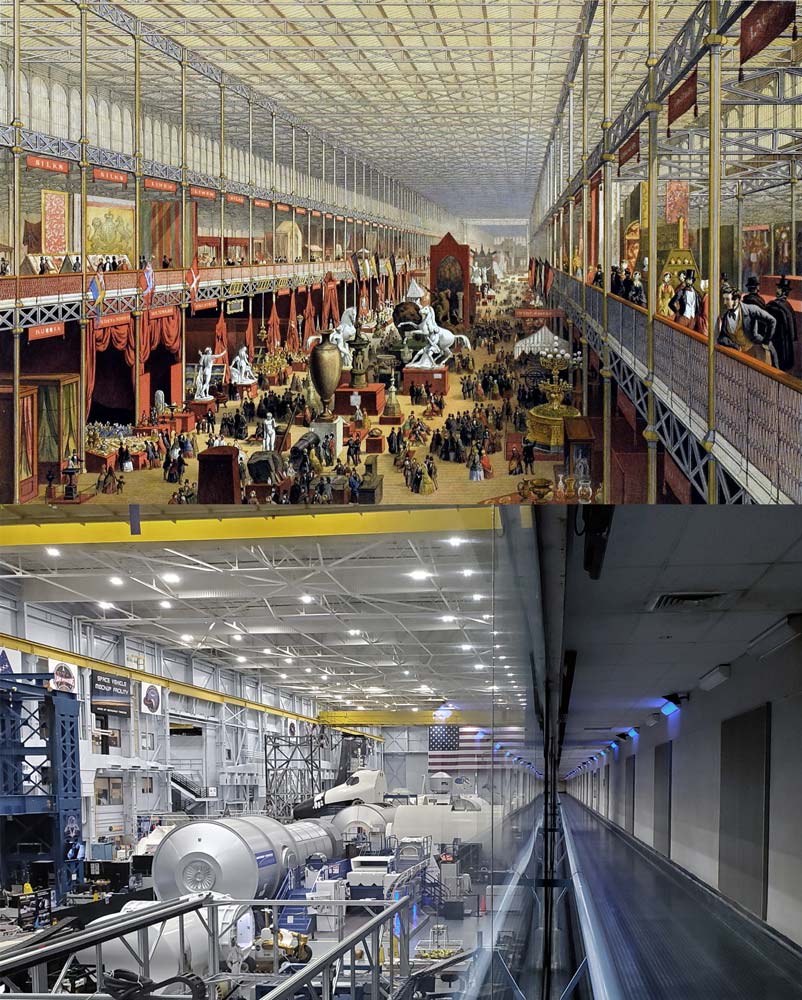

Crystal Palace, interior, Joseph Paxton, 1851, London, England and Space Vehicle Mockup Facility, Johnson Space Center, 2019, Houston, Texas, photo by Author

Crystal Palace, interior, Joseph Paxton, 1851, London, England and Space Vehicle Mockup Facility, Johnson Space Center, 2019, Houston, Texas, photo by Author

Astronauts Neil Armstrong, Mike Collins, and Buzz Aldrin departed from the Operations and Checkout Building on July 16, 1969. Famously pictured, this is the first moment the astronauts are seen by the public fully suited, carrying air supply systems, exiting the Operations and Checkout facility, and entering the wilderness of exterior space. Broadcast across the United States and around the world, the astronauts enter the Astrovan; it is this precise moment that the astronauts begin their journey to landing on the moon four days later. Televisions around the world tuned into the live coverage by broadcast journalist Walter Cronkite. The brief 15 seconds between the exit door to the NASA transfer van is the first and last moment the public will see all three astronauts together in their spacesuits before their return to Earth on July 24. Astronauts “exit” into the unknown wilderness between two concrete columns supporting the elevated catwalk above. This space is an empty exterior space situated between administrative offices organizing missions and spacecraft assembly constructing the most advanced modern machines; it is an American technological threshold for initiating the launch sequence. And here, the seemingly anonymous industrial-office building emerges as the 20th-century gateway to occupying extraterrestrial space and reaching the moon.

This broadcast “exit” was so synonymous with the lunar sequence that in July 2014, two years after Armstrong’s death, NASA announced the renaming of its Operations and Checkout facility to the “Neil Armstrong Operations and Checkout Building.” Commemorating the historical significance of the facility and its astronaut, the building now stands as an industrial artifact veiled by memorializing the astronaut who first set foot on the moon. In use today for assembling the Orion deep-space crew capsule, the Operations and Checkout Building in Florida stands as an enclosed technological garden for the commemoration of a nation’s wealth, intelligence, and power. Humans have reached the moon. Nature is completely transformed and is rendered through its extended technological ability to be conquered and made “magical and cosmic.”[8]

Contrary to the rise of “technofetishism and networks” like Archigram and Superstudio (Mitchell, 2003) as an architectural movement in the 1960s, the Kennedy Space Center truly absorbed the reality of technologically integrated networks and systems across vast spaces, on and off the Earth’s surface. And still, the architecture tends to subtly express radical techno-utopias and to offer an architectural vision that is dematerialized through its productivity: electronic, coordinated, and enclosed. Engrossed by the space program, Norman Mailer described the lunar landing module (LEM) as a “curious creature” that “had been designed from the inside, and so was about as ugly as a human body that had shaped itself around the excessive development of a few special organs.”[9] Mailer’s criticism of the LEM’s appearance could be described as a reflection of his hesitation toward postwar technological progress and its potential impact on the human condition. The “ugliness” of the exterior is certainly due to its rapid insistency on technological prowess, reflecting its departure from the machine in the shed to a shed as the machine.

As part of its power, both from the public’s perception and its desire to appear “advanced,” NASA and the US government needed to craft its image with a particular aesthetic, including its exhibition. To increase national support, the federal government continuously constructed an image, and its technology was the central figure. Borrowed from wartime aircraft hangars, the infrastructure of assembly became part of NASA’s image—a space for assembling and exhibiting its modern machines. Suspended in construction, floating in the long volume enclosure, the spacecraft was no doubt on display as a technological artifact for demonstrating political success. The Operations and Checkout Building’s high bay was not your average warehouse space. Highly polished white floor and a flat white ceiling with recessed lights make the space appear clinical, theatrical, or perhaps another world entirely. Occupied by dozens of mechanics in white lab coats and protective hats to eliminate particles from entering the assembly, the entire space was meant to appear synthetic. A laboratory for exhibiting the 20th-century machine and its process of assembly was born.

The idea of exhibiting the machine is not necessarily novel, however. The Crystal Palace, designed by Joseph Paxton, was constructed of large cast-iron frames. It was intended to increase the open space for enclosing international exhibition spaces for the Great Exhibition of 1851. Built like a glorified greenhouse, the Crystal Palace shaped the space for the most advanced technologies developed during its age. Because of its requirements to house such a vast number of exhibits, the production and technology that went into building the facility was just as much on display as the technologies inside. In contrast with the elaborate 17th- and 18th-century English gardens used for hosting dignitaries, the Crystal Palace inverts the perspective to the technological objects in its interior, thus removing the exterior environment from the scene entirely.

A strange continuity is found in the Operations and Checkout Building. In both cases, the long, uninterrupted volume showcases to the world its most innovative technology. The Crystal Palace’s innovation is the iron in its framing, while for NASA it is the ability to integrate the building into the process for assembling the technologically advanced machine. It is as if the machine could have never been constructed without the precision of its highly controlled environment that is separate from nature entirely. This time, however, the exhibition is not the products themselves, but the “concept of process,” a nation’s ability to achieve certain tasks against nature and to construct an image through an infrastructure of assembly as a synthetic stage for a global exhibition.[10]

Saturn V rocket inside Rocket Park, Johnson Space Center, 2019, Houston, Texas, photo by Author

Saturn V rocket inside Rocket Park, Johnson Space Center, 2019, Houston, Texas, photo by Author

Johnson Space Center’s Space Vehicle Mockup Facility demonstrates a very similar approach as it relates to NASA’s image for exhibiting its infrastructure of assembly. Perhaps even more analogous to the Crystal Palace than the Operations and Checkout Building, the Space Vehicle Mockup Facility in Houston allows visitors to traverse the entire 200-meter-long laboratory. After having traveled in a scripted tram, tour guides escort visitors up a flight of stairs into the large warehouse-like facility. Upon entering an elevated platform, much like in the Crystal Palace, visitors see on the exhibition floor a variety of artifacts from our recent past in space exploration. Staged with simulators and modern robots, the space seems more similar to a convention center than a truly robust factory for assembling the most advanced spacecraft in the world. Visitors are still not allowed to enter the Operations and Checkout Building in Florida now that private companies, such as Lockheed Martin, are assembling the spacecraft for the next manned flights into outer space. But in Houston, the Mockup Facility is exactly that, mocking up artifacts from the past and prototypes of the future—all intended for public display.

Two other notable stops on the JSC tram tour include the Apollo Mission Control Room and Rocket Park. Mission Control is located deep inside the labyrinthine structure of Building 30 with no windows to the outside world, though it is connected through communication signals to spacecraft orbiting the globe and Lunar Modules landing on the moon. After a recent renovation, the room now matches the 1960s era in every detail—including specific American-brand cigarette packs next to monitors displaying lunar flight paths and mission data—to appear as it did during the moment of the lunar landing on July 16, 1969. Separated by a glass window, visitors sit in stadium-like seating to gain a full access view in-situ of the display monitors used to control the historical spaceflights—an example of the American aesthetic in culture tied to an exhibition of the nation’s ability to coordinate and control missions to extraterrestrial space.

The concept of the garden in the machine is most evident in the Rocket Park, the last stop on the tour. The name itself indicates a strange relationship between the garden of strolls and modern machines involved in the Cold War politic. Resting horizontally on a steel frame, the celebrated Saturn V rocket is housed not in a glamorous feat of architectural engineering, but in a shed on the Texas landscape. Even more bizarre and tied to the concept of enclosing the garden, the rocket sits unnecessarily on artificial grass—the same “AstroTurf” first invented for sporting events in the uninterrupted and enclosed volume of the Astrodome. Only one of three Saturn V rockets exist, and this is the only one that is not made of simulated or mock-up parts; instead, it is composed entirely of certified and NASA-approved components.[11] And yet it sits in a shed immediately adjacent to Texas cattle grazing in the field. Under an exposed pre-engineered steel-frame shed lined with park benches along its side, the rocket becomes a caricature of itself in the so-called modern synthetic landscape in the United States. What can be said of our ability to produce an infrastructure of assembly through the particular forms of enclosure? The material and volume of the space curate a memory of its antecedents—modest horizontally assembled rockets in aircraft hangars from the early 1950s. Once rendered as an artifact, the rocket’s enclosure remains synthetic but an object on display, not for assembly or even to capture the aesthetic of its process. The machine is enclosed in the shed, but this time it is presented as an object of the nation’s technological garden.

Space settlements hurling through space offered something of an inverse description. In other words, space settlements illustrate a representation of the Earth’s environment inside the spaceship machine. Space settlements were visualized as gardens in the most literal way: environments in a rotating enclosure sealed off from the vacuum of space.[12] But curiously, the natural wilderness on Earth is completely disassociated from the production and assembly of tools, vehicles, and satellites that attempt to project an enclosed garden of utopia floating in space. And, therefore, the infrastructure of assembly as an enclosed system more directly reveals architecture’s immediate associations with the process of machine assembly. The garden was neither a representation of a natural environment nor a synthetic construction of some American ideal landscape. Coincidentally, and often overlooked, the enclosed architecture, aligned with processes in assembly throughout the spaceport complex from 1957 to 1963, constructs a new garden entirely. The machine encloses assembly processes, and while producing an image for showcasing the concept of process, it replaces the wilderness overcome by the technological figure.