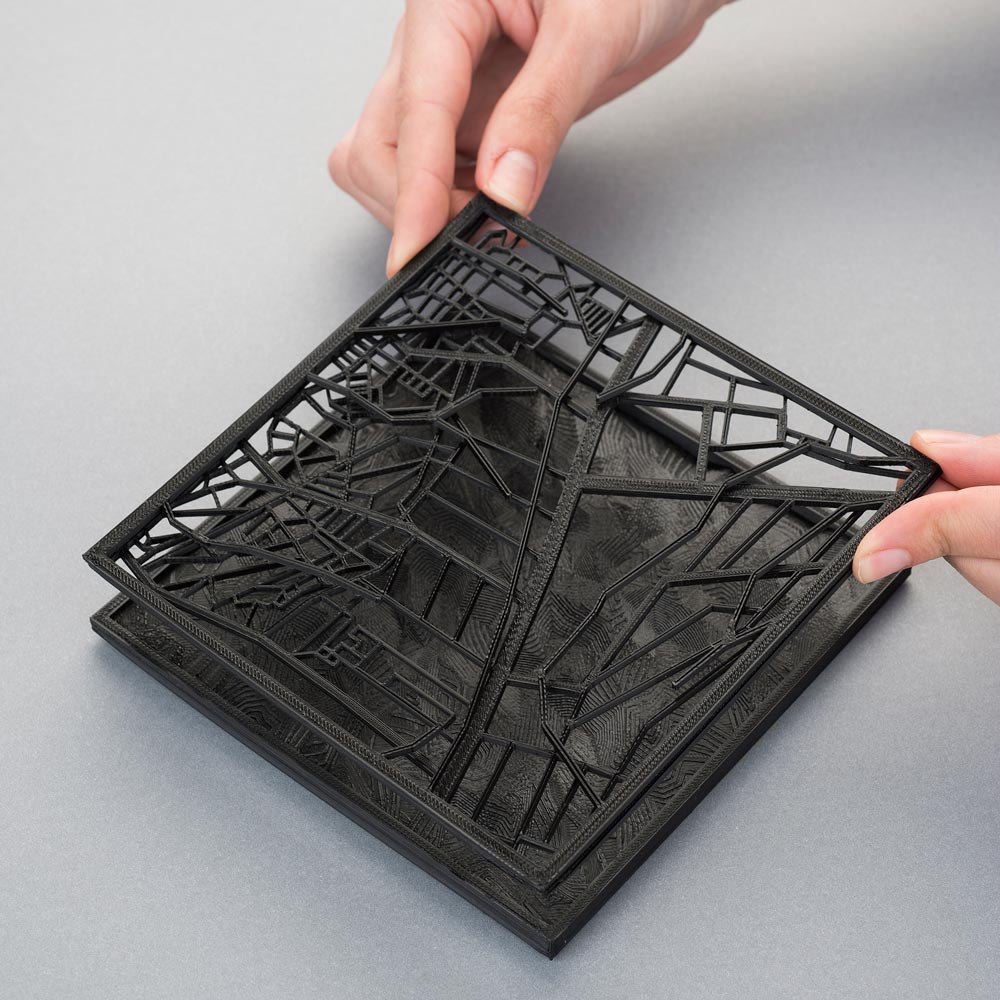

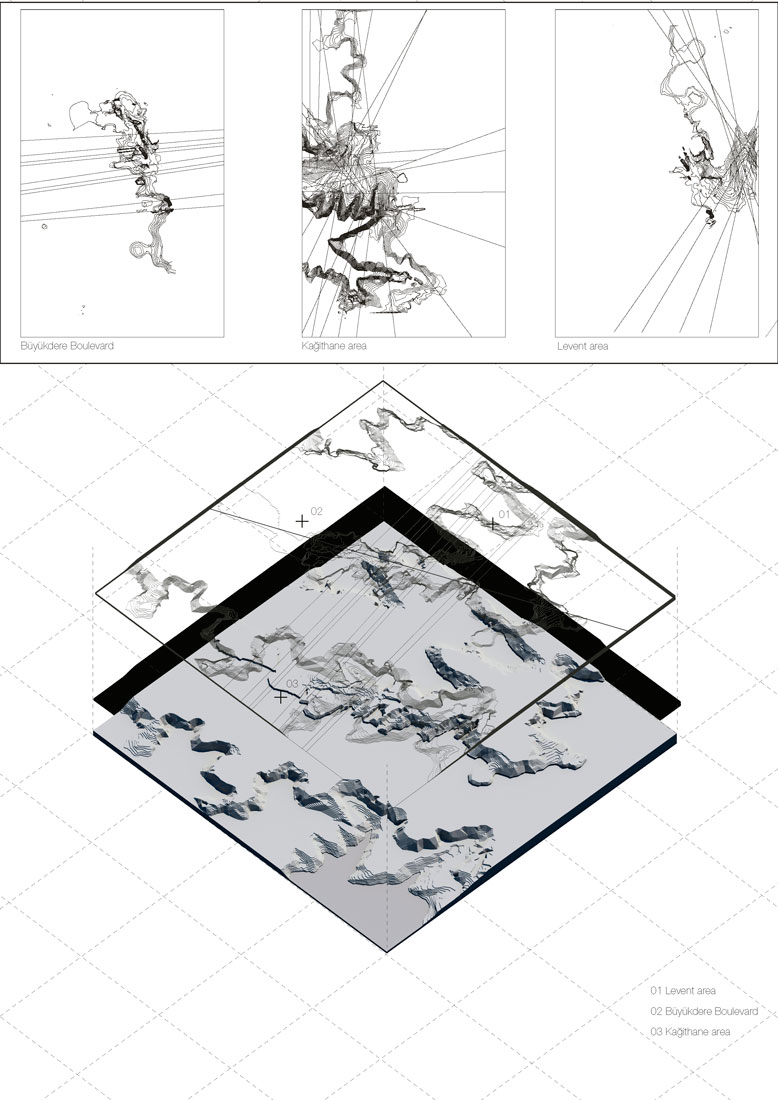

Modalities of Spontaneous is a series of reliefs, generated through an investigation of the transformation of urban texture and exhibited in the 14th Venice Architecture Biennale in Turkish Pavilion as a part of Places of Memory Exhibition. Inspired by the chaotic development of Istanbul, the work dismounts urban fragments of the city, tracing today’s notions to the past and back.

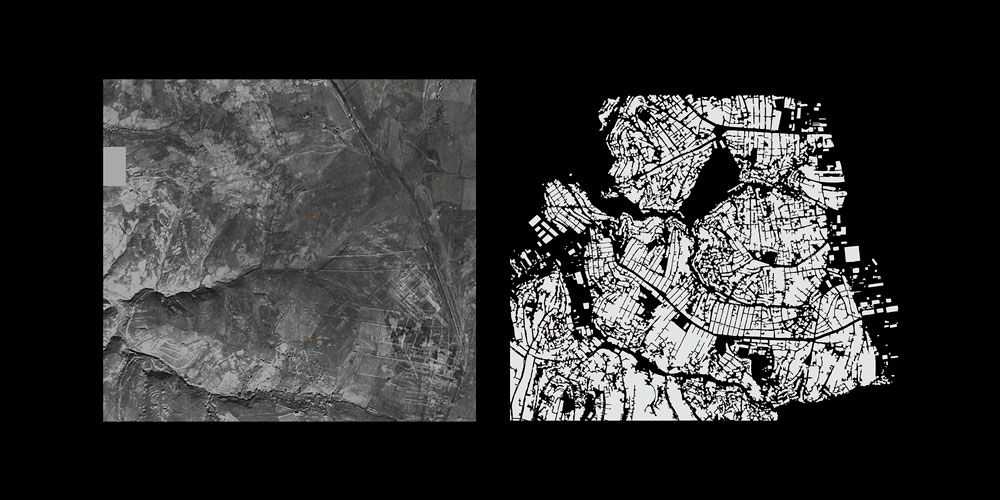

A pure formal study with topography and ownership borders at the start, reveals that the contemporary distribution of functions in the urban space. A very old main artery, transformed into the main business axis is located on the ridge, creating two slopes with different climatic characteristics, which later evolve into two different neighborhoods with different physical and social qualities. Former agricultural divisions, have been adopted as the borders of following industrialization and the same property ownership led to recent big multi-functional buildings, shopping malls and office towers to be built on the same spots. Extensive studies based on built environment, infrastructure and buildings realized mostly after 1950’s, their informal extensions and comparisons between different fragments show further evidence of topography and the infrastructure which was shaped accordingly being strong actors in the formation of urban space, accompanying socio-economic and political dynamics.

A unique example of non-western modernization, Istanbul’s urban stratification reveals important hints to understand stories behind major political decisions, investment shifts and continuous reorganization of the city. As a new research method to understand and represent “Emerging Market Countries’ evolutionary urbanism”*, Modalities of the Spontaneous is analyzing the urban strata, layer by layer and aims at understanding the order of what appears disorderly.

Territorial Receips for Istanbul

Although the Taksim-Karaköy interval, another work area determined within this scope, is quite different from Levent in terms of the period the general urban fabric took shape, both its spatial distribution and story of development display specific similarities. Despite the fact that its architectural environment appears different, an observation based on ratio and function reveals interesting similarities.

The development that changed Beyoğlu’s fate, was the opening of the funicular in 1874, the second underground public transport system in the world after London’s. The 573-meter connection, linked the city centre based in the triangle of Perşembe Pazarı [Perşembe Market], Bankalar Caddesi [Bankalar Street] and Karaköy Harbor to Tünel Square, the highest point of the area, thus extending the dynamism of Galata along İstiklal Caddesi. This opening pioneered the developments that resulted in İstiklal Caddesi, the longest promenade of Istanbul, extending towards Taksim Square, and becoming the backbone it is today. It is also the first section and first example of the Büyükdere axis, which, to use Murat Güvenç’s phrase, is the “architecture museum of the city”, and today extends from Taksim to Şişli, from Şişli to Zincirlikuyu, and from there to Levent and Maslak. Triggered by the Tünel connection, İstiklal Caddesi came, from the late 19th century on, both the business center and the social lifeline of the city. Its topographic ridge, or in other words, the axis that follows the highest point of the area to reach Taksim Square, precisely like in the continuation of Büyükdere, places its western and eastern slopes in its center. The eastern slope facing the Bosphorus, more advantageous because of its proximity to the coast and to Salı Pazarı [Salı Market], forms the more attractive section of the ridge. On the other hand, the western slope facing Kağıthane Valley, in other words, the sloped area which today descends into Kasımpaşa via Tarlabaşı and forms the other part of the topographic trajectory, has a less advantageous position in terms of acclimatization and is home to the lower-middle class. These two slopes of a hill with the same incline are thus differentiated in terms of physical conditions, and also become the scene of a visible social differentiation. The eastern slope is the center of attraction, while the western slope is secondary in terms of demand. The outcome of the difference in demand triggered by geographical conditions indicates the divide that is still visible today. We encounter the ratio of the facade facing the street and the side facade along the Büyükdere route, on İstiklal Caddesi as the ratio of a narrow facade and deep-set width. Thus, it is possible to read as an urban definition the repetitions produced by the central axis and the echelonment it forms towards lower elevations, which we observe in Levent, and see once again on İstiklal Caddesi.

Juxtaposition; spatial textures we encounter in settlement plans and sections of plans; and infrastructural decisions that determine the thresholds of the city stand out as concepts repeated in all three chapters. When we hold the lens provided by inferences made in Büyükdere to various other parts of the city, as we did in the topography and thresholds section, we come across similar organizations. In the final chapter, the counterpart along the Taksim-Karaköy route of this chart that was obtained with this lens is examined, and this once again reveals the order of what appears disorderly.

Today, in cities like Istanbul which continue to develop, the formation of the architectural environment is controlled by contemporary dynamics such as neoliberal policies, global capital and the privatization of public space. This urban environment, shaped by various deals and balances of power, and sometimes coincidences, might create the impression of a development so out of control that it creates disquiet. However, a different viewpoint is possible if we expand the spatial scale and historical scope we focus on. Within this scope, beyond the visible factors that trigger the formation of momentary operations, and independently of such characters, it is important to remind of the existence of essential actors, like the multidimensional memory of space, that weave together the past and present, and architecture and the city.