Rock. Nail. Time. A puzzle can be as simple as three seemingly unrelated words placed side by side. Their adjacency signals a veiled connection, capturing our attention. Bed is here the linking word—riddle solved.[1] Puzzles throw a net of mystery over everyday stuff. Consider the corny images typically printed on jigsaws—Kittens! Lighthouses! Santa!—that often disguise a sophisticated network of pieces. To get to the heart of the challenge, many jigsaw aficionados prefer to work on blank puzzles or puzzles with pieces so interchangeable that their assembly points toward thousands of incorrect solutions.[2]

Like puzzles, the expansive surfaces of architecture are routinely covered with interlocking elements that combine graphic and constructional qualities. But the tiling systems, or tessellations, used for jigsaws are bound to a 2D surface; one that lies politely on a tabletop. Whether made from cardboard or wood, these parts remain thin. The surfaces of buildings, on the other hand, move through space at multiple angles and capture volume in a variety of ways. In architecture, the 2D methods that organize tilings of panelized materials are always in contact with the 3D realities of built surfaces.

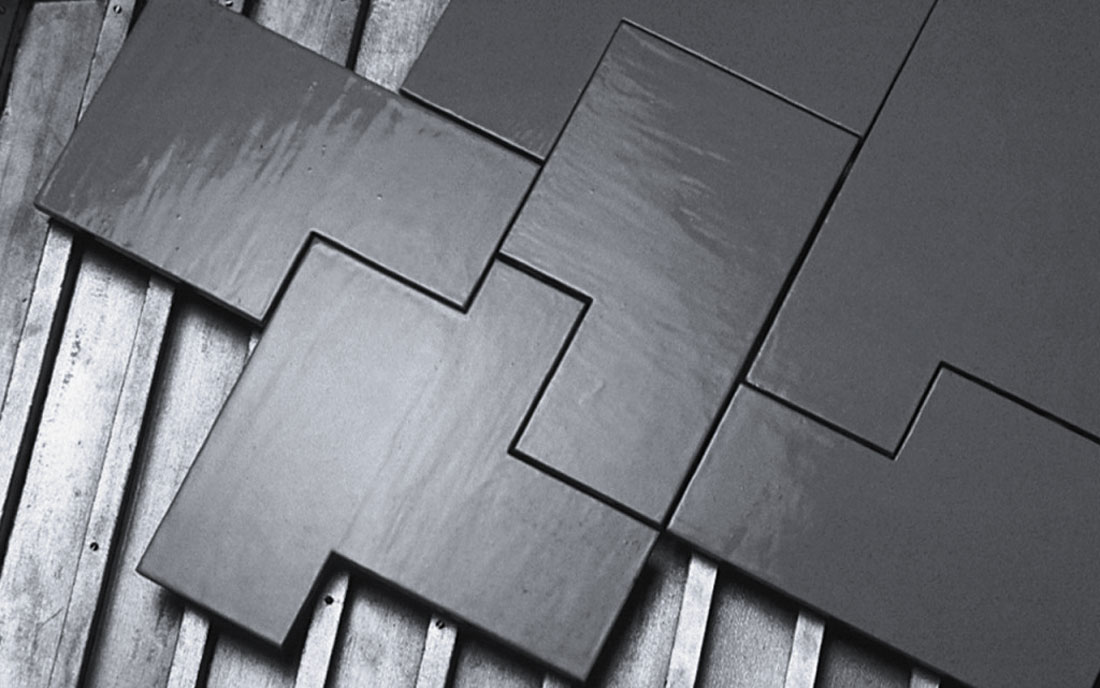

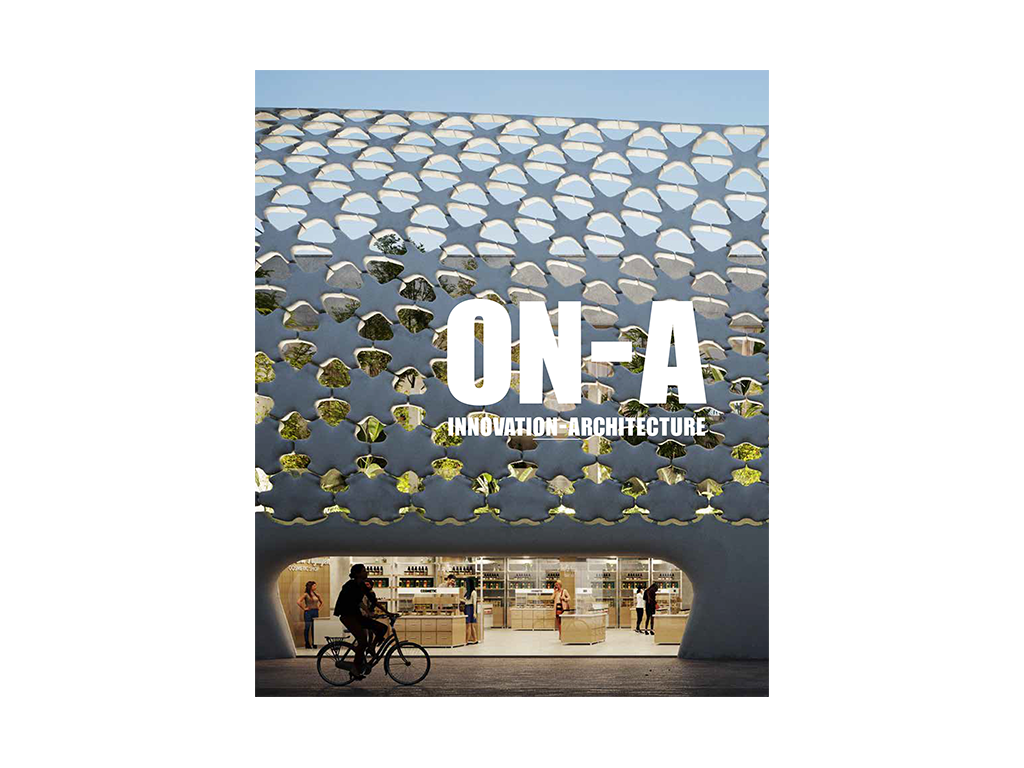

Fig. 01: The Fractile was developed by Cecil Balmond to cover the façade of the Victoria and Albert Museum Spiral extension designed by Daniel Libeskind

Before digital tools made designing complex surfaces easy, these 3D realities were tamer. Architectural containers were usually upright and geometrically uptight, tiled with rectangular panels. Now architects aggressively cut and fold surfaces into complicated origami; we loft them from complexly shaped profiles and stretch them into freeform shells. Capturing sophisticated internal volume with gymnastic 3D surfaces is the new normal in architecture. To underscore this enthusiasm for geometric complexity at every level of building, architects regularly subdivide surfaces into tessellated patterns that rival any jigsaw puzzle.[3]

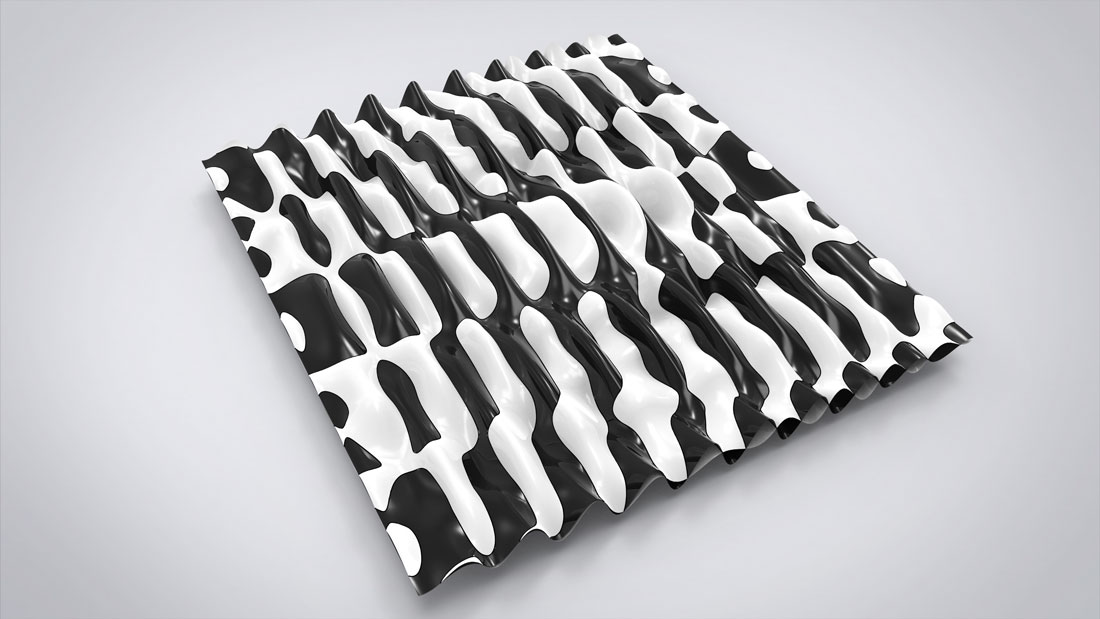

Fig. 02: A graphic, volumetric tessellation study by Justin Diles

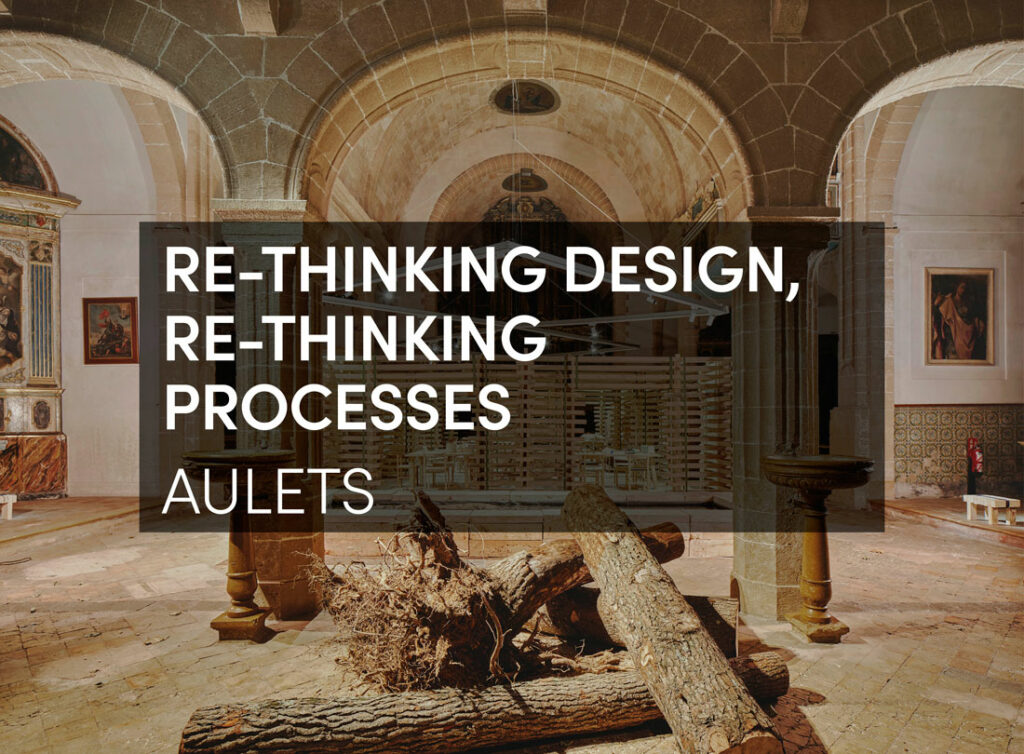

These tessellations are often dazzling; yet, typically they have little to do with how a surface is organized inside. Has a fuller exploration of the relationship between a surface’s interior and exterior been hindered by an old-fashioned approach to tectonic assembly—one that privileges lightweight structural frames dressed with thin skins of cladding? Daniel Libeskind and Cecil Balmond’s remarkable V&A Spiral proposal—a pioneering project that was critical in establishing current tactics for designing surface and cladding—illustrates this persistent division. The building’s central, twisting strip is a thick structural surface (comprised of steel framing) that sweeps upward according to its own internal logic.[4] An equally innovative system of algorithmic, non-repeating façade tiles is applied to this surface (Fig. 01). The tiles animate the spiral while remaining fundamentally unconnected to the thickness of the wall, covering it like wallpaper.

Fig. 03: The Plasticity Pavilion is a foam and fiberglass construction composed of large, nested elements.

What would happen if architects decided to merge the patterning schemes applied to a surface with its overall depth? Patterns could begin to structure surfaces, not just lightly dance on top of them. Systems of tessellations with dimensional relief might operate like mosaics with deep, integral volume (Fig. 02). [5] Wave-like surfaces—especially those procedurally rippled by algorithms—could become ideal sources for making tessellations of this type since they bounce up and down, unwilling to lay flat. We might search for new techniques that apply puzzle-like patterns to both free-form single surfaces and closed surfaces—like spheres and prisms—that define architectural volume. And we might seek out systems that produce interlocking patterns that completely wrap surfaces like jigsaw puzzles that learned how to bend, overlaying and penetrating once blank architectural masses with mysterious networks of parts (Fig. 03).