The fallowing of land implies that a process of resource extraction has previously occurred. It suggests a period of intentional recovery and rest for a territory that has recently served an anthropogenically productive purpose. And it also intimates that said productive purpose—or a similar one—will soon be reinitiated on the territory in question as part of an ongoing process of land cultivation and management. In this way, to lie fallow suggests both an active, productive past and—more importantly in the context of design and planning praxis—an equally active and productive future.

Tamensourt, Morocco: the first new town constructed as part of the state’s ambitious 2004 Ville Nouvelle program.

Despite the potential parallels between agricultural and urbanization regimes, this familiar sequence of operations (extract, recover, extract) does not so easily apply to land that has been subjected to contemporary speculative urbanization practices.[1] In these cases, once value has been extracted from a piece of land—either economic value through a series of transactions, or environmental value as a result of stripping and denuding landcover—there is neither the guarantee of recovery or regeneration during the “fallow” period, nor the assurance of future productivity through occupation.

Regardless of the recent academic rhetoric on process and emergence, this reality manifests itself in contemporary urban planning and design practice that is still characterized by the emphasis on outcome—or the image of outcome—above all else. As others have argued, this suggests urbanization is increasingly understood as the manufacture of a saleable product, whether physical or financial, rather than the structuring of an ongoing process capable of accommodating settlement, culture, and commerce.

As I have written elsewhere, examples of speculative urbanization activities can be found throughout recorded history but have notably escalated in physical scale and intensified in frequency over the last 20 years.[2] Familiar Western examples of the failures of these activities from the early 21st century include Ireland’s so-called Ghost Estates; the substantial production and abandonment of suburban housing throughout the US Sunbelt during this same period; and most dramatically, the massive building boom and corresponding economic bust that took place in Spain between 1998 and 2012.[3]

Overview (looking southwest) of El Cañaveral housing development at the eastern periphery of Madrid, 2014.

While most recent examples represent cautionary tales, some speculative urbanization endeavors from this same period are seen to have achieved varying degrees of success. In the Middle East, for example, both Dubai and Abu Dhabi are seen as offering replicable models of urbanization-driven economic success tied to the production of spectacular (thus highly desirable to foreign investment) urban form. And then there is of course China, which arguably has pinned much of its desire to realize a mature consumer economy squarely on the back of a real estate and construction-driven transfer of capital.[4]

Despite the range of sociocultural, economic, and political contexts in each of these and other examples of speculative urbanization, there is a set of consistent underlying conditions central to its production. These include the projection of a rapidly expanding population; belief in the need for upgraded and expanded urban facilities, in particular housing and mobility infrastructure; and the prediction of a corresponding economic boom as a direct result of projected population growth. That is, while speculative urbanization occurs in all politico-economic geographies—from state-controlled communist governments to privatized neoliberal markets—the phenomenon is most likely to occur within those polities with economies characterized as emerging.

Given the perception of success regarding speculative urbanization activities in places like China and the Emirates, their particular urban growth models and protocols are viewed by many actors in developing contexts, both state and private, as worth emulating. And it should be no surprise that these entities actively peddle their expertise in executing these models of urbanization-driven economic growth in contexts with which they have very little in common. However, despite outward impressions of accomplishment, the actual degree of economic, urbanistic, and other successes remains a serious question.[5] For example, significant state intervention is often required in these cases to subsidize or catalyze the all-important initial occupation of the settlement or to encourage occupants to remain years after so-called completion.[6]

History has shown there is an enormous economic and environmental risk associated with most large-scale speculative urbanization activities, via incompletion, low-occupancy, abandonment, and so on. Thus the potential consequences of exporting these models should not be discounted. And in fact, the urban design disciplines in particular must question their role in such activities, and the implications of promoting these urbanization-driven economic growth models in contexts that lack both the political control and sufficient economic resources of their source contexts.

A New Epicenter

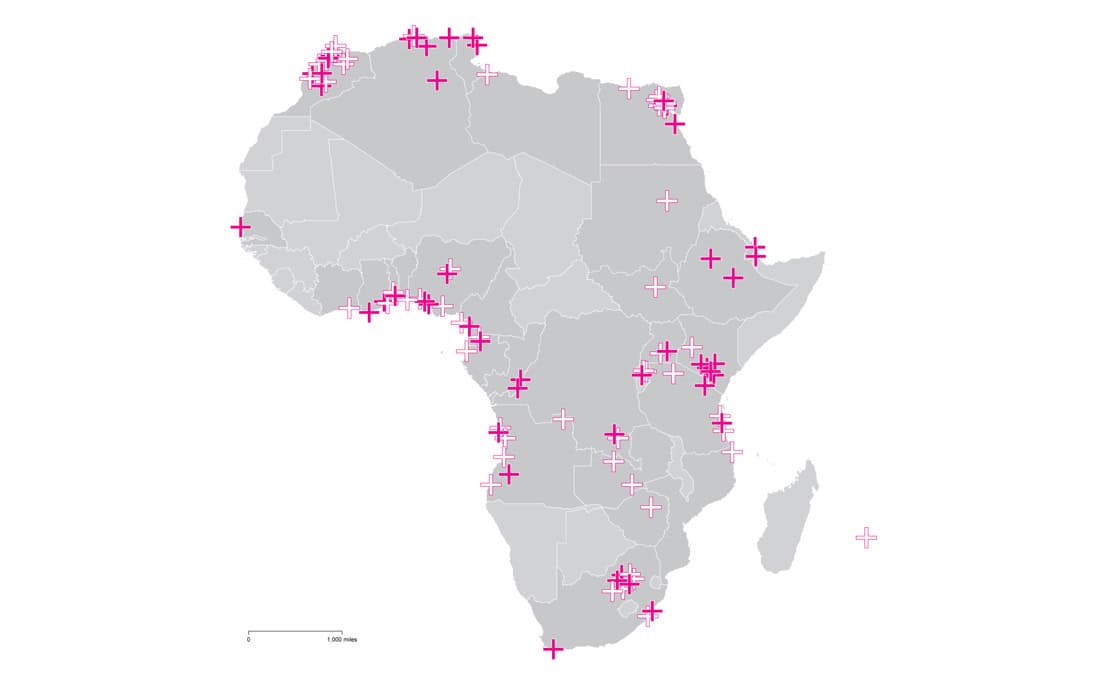

Here, it is worth noting a new epicenter of speculative urbanization activity that has emerged in the decade since the most recent global financial crisis. Tracing back to 2005—the peak of the most recent real estate-driven economic recession—one finds the rapid proliferation of new town schemes proposed for geographies across the African continent.[7] My ongoing research has identified no fewer than 120 such projects at a scale of at least 300-hectares or more (with most coming in between 1,000- and 4,000-hectares) each oriented towards one of nine familiar urban typologies.[8]

Map of African continent showing location of 100 new town projects proposed or initiated since 2005.

The projects identified in this work are located almost exclusively in exurban or peri-urban greenfield sites, well outside the frenetic complexity of existing urban centers.[9] The rhetoric and propaganda accompanying these proposals unsurprisingly suggests they are motivated both by the urgent need for upgraded housing and infrastructure due to considerable population projections, and the deficient physical state of extant urban centers and their infrastructures.

Yet despite the unquestionable need to enhance both formats of settlement and infrastructure throughout the African continent, the incongruity of the exogenous models employed by these proposals relative to their destination contexts threatens the ecological value of the land they are planned for, as well as the political and economic stability of the governments often advocating for them.[10] Given the potential scale of these speculative urbanization activities—and in turn, the potential commensurate consequence of their failure—new contingent-based approaches to the physical planning, design, and initiation of urban settlement and infrastructure in developing contexts is urgently needed.

But before delving into a specific discussion of speculative urbanization in Africa and the priorities of alternative approaches to the planning of speculative settlement, it is worthwhile to frame these activities in terms of this journal’s theme of “fallow,” and by extension, the bigger question of managed recovery from extractive anthropogenic activities.

Urbanistic Extraction

Speculative urbanization often takes one of two forms; both of which result in a landscape whose value has been extracted. One version, which I will refer to as Plans and Proposals, operates in the realm of legal and financial urbanistic activities, in other words, in the nonphysical. The other, Preparation and Plots, is perhaps the more familiar, encompassing the physical activities associated with urbanization.

Plans and Proposals can be characterized as transactional, and often begin with the planning of a piece of mobility infrastructure. Regardless of whether any part of the plan is executed, this activity has the immediate effect of raising the market value of proximate lands. Here, in theory, landowners benefit from the proposal either through increased property values, or from returns received through a process of expropriation. Once infrastructure planning is initiated, adjacent property value is further influenced through changes in land-use designation or other zoning modifications. These relatively simple procedural activities have a direct impact on the market value of a territory, often leading to its eventual sale and resale.

These land-use modifications often follow the execution of a development proposal for a piece of property. This most basic of urban design activities—the plan—is thus enormously powerful. Even the most improbable or irrational proposal will serve to escalate the market’s perception of a parcel’s worth. The plan implies possibility. It suggests imminent transformation, although it matters little whether there is any intention of it ever being executed. Rather, the plan’s “utility,” is that it attracts capital by demonstrating potential.

What is extracted under this form of speculative urbanization is value; some might even say, artificial value. While the losses associated with this extraction are not physical, they are no less consequential. The tenure of the land has been fundamentally modified, and in some cases, forcefully taken from the original landowners. In turn, the potential to use the land in question for specific “low-intensity” purposes is invalidated because of its market value escalation. Land that was once productive is no longer so, at least in terms other than financial.

The second form that speculative urbanization takes is conspicuously more physical. Here land is cleared of flora and fauna; topography reshaped; watercourses diverted or channeled and covered; and ribbons of impermeable surfaces laid over formerly absorbent soils. Beneath these asphalt and concrete roadways lie miles of wire, conduit, and piping. In the parcels created by these corridors, myriad excavations are undertaken that often lead to the off-site disposal of considerable volumes of formerly fertile earth.

At the conclusion of these activities, the site is considered “prepped”—awaiting the deployment of massive amounts of concrete, steel, and brick. All of this energy and material is deployed in anticipation of a population that may not ever arrive. This is the most common state of speculative urbanization—a denuded, incomplete urban territory whose value is no longer measured in ecosystemic terms, but rather in terms that are simultaneously political and economic. Here, no amount of remediation, greenwashing or fallowing can serve to undo a potentially permanent condition oriented towards an aspirational if dubious urban future.

Oyala, Administrative City of Djibloho, Equatorial Guinea: new capital city initiated following the country’s discovery of oil and a coup attempt on the president in 2004.

There has been a great deal written recently, particularly from environmental planning and critical geography perspectives, on the implications of extractive anthropogenic activities. This discussion has principally focused on the removal of physical materials from the ground—mineral resources, fresh water, commodity-related biomass—and the severe environmental and social consequences of this activity.

Extraction in the context of speculative urbanization, however, is different. As noted above, there are significant environmental implications. But what is extracted in these cases—what is permanently lost—is as much fiscal as physiological; both economic and ecologic. The potential implications for those polities and populations involved in such pursuits are, in turn, no less catastrophic.

Speculative urbanization activities inherently reject academic notions of the urbanization process or development in time. Or at the very least, they actively attempt to bypass the idea. Such activities are oriented for the near-term, motivated by immediate returns rather than long-term resolutions. More often than not, they are announced and executed (to varying degrees) on the schedule of local elections or in response to financial markets. Land is held for the minimum period possible to achieve a desired return before the acreage is disposed. Long-term management is of little interest, which shapes how these settlement proposals are conceived and planned. Speculative urbanization activities are motivated by a game of financial hot-potato dependent on interest rates and debt repayment schedules, rather than the equitable occupation and activation of urban form.

As a result, the role of urban design in these activities is often pointed towards the production of glossy, implausible, contextually incongruous renderings produced for political propaganda and to attract exogenous investment. Press releases and marketing materials are filled with aspirational references to the needs and desires of a so-called “growing middle class”—really, the consumer class—and present speculative settlements in the ethical terms of socioeconomic opportunity and access. Yet the reality of who can afford to occupy the proposed developments, particularly in emerging economies, is very different. Contradictions between promotional rhetoric and conditions on the ground are almost satirical: Luxury housing in the context of rolling blackouts; global retail opportunities in lieu of educational opportunities; high-rises before healthcare facilities. In this context physical urbanization, or at least its planning, functions as a kind of prop. An image of aspiration whose terms and currency are set by global capital and its affinity for the perceived economic successes found in the polities of China and the Middle East.

Extraction in the context of speculative urbanization is very much about the creation and mining of artificial capital value, and the creation and off-loading of debt. And in many cases, creating access to markets and other natural resources (i. e., conventional extraction) in exchange for the production of (images of) urban form. It has nothing to do with the aspirational platitudes or socioeconomic valorization of urban form. Rather, speculative urbanization in the 21st century is about attracting capital and expressing geopolitical significance.

As a result, urban designers today have become the Mad (wo)Men of the Global South; the Don Draper’s of urbanization—selling an image and ideal of the 21st-century city that is more or less impossible to achieve. The optimism and good intentions of the modernist project of urban design have, in this context, metastasized into a “hand measuring contest”— to use the words of the US real-estate-developer-in-chief. This has led the familiar acronym-named design practices of the world, among many others, to proliferate grandiose plans and images of an idealized urban future with limited attention paid to the processes of getting from the realities of now to the ambitions of such fictions.

Whether these urbanization projects are executed fully does not really matter. Physical urbanization—both proposed and executed—has become a prop, a signifier of opportunity for impatient capital. As such, the thinking often goes, the more ambitious the project, the more appealing it must be to potential investment.

Volatility + Risk

Economic geographer Bent Flyvbjerg has written extensively on the volatility of what he terms “megaprojects”: large-scale initiatives including transport infrastructures, telecommunications networks, cross-border pipelines, transnational power grids, and the like that have a “strikingly poor performance record in terms of economy, environment, and public support.”[11] In Flyvbjerg’s research “poor performance” implies the increasing correlation between environmental degradation, social disenfranchisement, severe capital loss, political instability, and the pursuit of increasingly ambitious construction projects that have become de rigueur for demonstrating global competitiveness and political power.

Despite significant differences in type and promoter (both public and private), Flyvbjerg and his colleagues have identified a set of deficiencies or negative characteristics that are consistent across projects of this scale. These include 1) substantial cost overruns; 2) “strategic misrepresentation” by project promoters (exaggeration or spin); 3) lower than estimated usage relative to demand forecasts (exacerbating cost overruns); and 4) greater than anticipated environmental impacts, both during implementation and occupation. To put it another way: mega-urban projects always cost much more than estimated, and always serve far fewer than projected.

The relevance of Flyvbjerg’s research to speculative urbanization should be obvious. While much of the scholarship on “megaprojects” focuses on infrastructure, its characteristic deficiencies are translatable to the large-scale urbanization projects discussed here, precisely because of the infrastructural interventions at the basis of their undertaking.[12]

Central to Flyvbjerg’s analysis is a phenomenon known as “optimism bias”; or “appraisal optimism,” as he terms it.[13] This is the cognitive tendency for some actor or agency—government, institution, corporation, planner, and so on—to believe they are less susceptible to experiencing a negative event relative to an ambitious pursuit compared to others in similar circumstances, despite clear proof to the contrary in the form of past events. The presence of this “optimism” in the planning of large-scale urbanization endeavors manifests itself most frequently in the exaggerated potential of a project. Yet this exaggeration is not difficult to identify. Expressive phrases like “this time will be different,” or “that circumstance is not applicable here,” or “our market projections are sound,” and “this project is not like the others” are strongly indicative of impending disruption and potential failure.

The phenomenon of speculative urbanization has shown us that when one is told not to worry, it is precisely the time to worry.

Arable Land

Returning to the theme of fallow and the implications of unchecked speculative urbanization across the African continent, there remains the question of arable land.

Between 60 and 65 percent of the world’s uncultivated arable land—approximately 600-million hectares—is located in Africa.[14] Among a great number of natural resources, this is perhaps the continent’s most valuable. Despite what seems like an enormous quantity of arable land (roughly twice the size of Argentina), in the next three decades the continent’s population is projected to double to approximately 2.4 billion people. By 2100, there will likely be close to 4.4 billion people living in Africa, accounting for roughly 40 percent of the total population of the earth.[15] If ever there was an excuse to build, these population projections are it.

Chefie housing estate at the eastern periphery of Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Part of one the largest social housing initiatives ongoing on the African continent.

To put the risk of speculative urbanization in some context, consider relatively recent events in Spain. In a 10-year period between 1998 and 2008, during that country’s settlement- and infrastructure-driven economic boom and bust, roughly one-third of all urbanized land was created. This urbanization produced 7 million new homes, roughly 1.5-2 million of which remain empty more than a decade later. At the beginning of this period there was a need, and even demand, for housing in Spain, but never enough for the settlement that was actually produced. Contemporaneous speculative urbanization events in Ireland were similar: clear demand, extreme surplus production.[16] Even China, with its vast state-controlled expansion of settlement and infrastructure over the last three decades, established a so-called “red line” of reserved arable land in 2007 to ensure the country’s food security and prevent urbanization from rapidly eroding agricultural land.[17]

Now extrapolate these failures to the real housing demand on the African continent at present, and the speculation that will inevitably companion this production. The potential economic and political disruption to governments and economies that are far less mature than the preceding examples, that also lack bailout mechanisms like the European Union and the Central People’s Government, cannot be overstated. And the potential environmental consequences are even more daunting.

Significant loss of arable land is already occurring in rapidly urbanizing contexts like Kenya. As a recent New York Times feature notes: “Population swells, climate change, soil degradation, erosion, poaching, global food prices, and even the benefits of affluence are exerting incredible pressure on African land.”[18] Given that the continent is the new epicenter of global speculative urbanization practices, we can only assume that this remaining arable land—and its corresponding ecosystem service capacity—is under extreme duress.

A new road under construction as part of a large “middle class” housing estate being privately developed outside of Nairobi, Kenya.

Landscape architect Richard Weller has illustrated the emerging conflict between rapidly expanding urban form in the Global South and the remnants of the earth’s most important pockets of biodiversity in his Atlas for the End of the World (2017). Weller identifies no fewer than 70 cities whose projected growth will consume and permanently destroy significant portions of the African continent’s nine biodiversity hotspots.[19] Yet these “hotspots” represent only a tiny fraction of the continent’s overall ecosystem service capacity that is under threat due to, among others, intensifying speculative urbanization practices.

Conclusion

Which brings us to the essential question at the root of this ongoing research into the phenomenon of speculative urbanization: how do we, the urban design disciplines, plan and design for future urban conditions fundamentally characterized by the risk of failure or incompletion, not to mention, that are profoundly at odds with the ecosystem service capacity of the sites in question? The answer is not a matter of better, or smarter, or more bottom-up; but rather an essential reorientation of disciplinary priorities.

Without a doubt, design and planning rely on the notion of optimism bias discussed above. Disciplinary work is rooted in expressing the ambitions and aspirations of a potential future. But to disregard the inherent volatility and risk associated with design and planning at the global scale discussed herein is both irresponsible and unethical. As such, acknowledging the reality of this volatility indicates the need to retool contemporary urban design and planning praxis so as not to adversely contribute to, or further exacerbate, the consequences of more and more common 21st century speculative urbanization practices.

Incidentally, one of Flyvbjerg’s conclusions regarding the proliferation of megaprojects should be a fundamental conceit of contemporary urban design praxis: risk cannot be designed out of speculative urbanization, or urbanization in general.[20] Actively planning and designing for uncertainty and failure instead creates systemic frameworks that allow an urbanization project to be reliably recalibrated and readjusted over the extended timescale of its implementation and—hopefully—occupation.

Rather than focus on the preferred outcome of a proposal for new settlement—as most contemporary planning of new settlement often tends to do—a retooled urban design praxis would elaborate strategies to exploit the transactional motivation behind these speculative proposals in support of alternative urbanization logics. Near-term protocols could be redirected to examine the efficacy and value creation of planning and design strategies that manage and cultivate speculative urbanization practices over time. This would require approaches to the planning of settlement rooted in contingency, disposability, and synthesis—not outcome.

In many ways, the interim state of the urbanization process—after initiation, before occupation—can be understood as a kind of fallow state. Treating it as such, however, necessitates fundamentally reconsidering both how a project begins, and the unpredictability of its future. Until urban design praxis engages this uncertainty, it maintains complicity in the potentially catastrophic consequences of 21st-century speculative urbanization.