Architecture has recently renewed its fascination with the notion of environment, as a dynamic and an atmospherically tangible space of design. This has been driven by a number of trajectories and positions within the discipline. On the one hand, the ever-expanding discourse on sustainability has brought debates of technology-driven versus passive means of control to the fore. On the other hand, architecture has embraced responsive design anew, testing the possibility of environments that contain instruments for sensing and responding to atmospheric conditions and human occupants. Simultaneously, responsive design has sought out biological and ecological models, embracing the notion of architecture an as organism able to physically react to changing interior and exterior environmental conditions.

Mechanical ballet: ALMA’s sixty-six antennas rotate in a synchronic movement.

Reacting to the strictures of modernism, interest in ideas of environment and “soft” architecture served as a provocation to conventional models of architecture, and was part of a design counter-culture, foregrounded in architectural discourse in the 1960s through to two trajectories. Architects Buckminster Fuller and Francois Dallegret, and theorist Reyner Banham, as well as several Viennese and British architects[1], were advocating for architecture to reduce—if not shed entirely—the envelope of architecture, in favor of more technological means of producing controlled environments. In parallel, architects were speculating on the possibility of environments driven by informational feedback mechanisms rather than atmospherics. Recent renewed interest in the writings and work of this constellation of thinkers has influenced an evolving set of discussions and design provocations, centered around the consideration of environment and its external linkages.

Environment of Control / Thin Skin

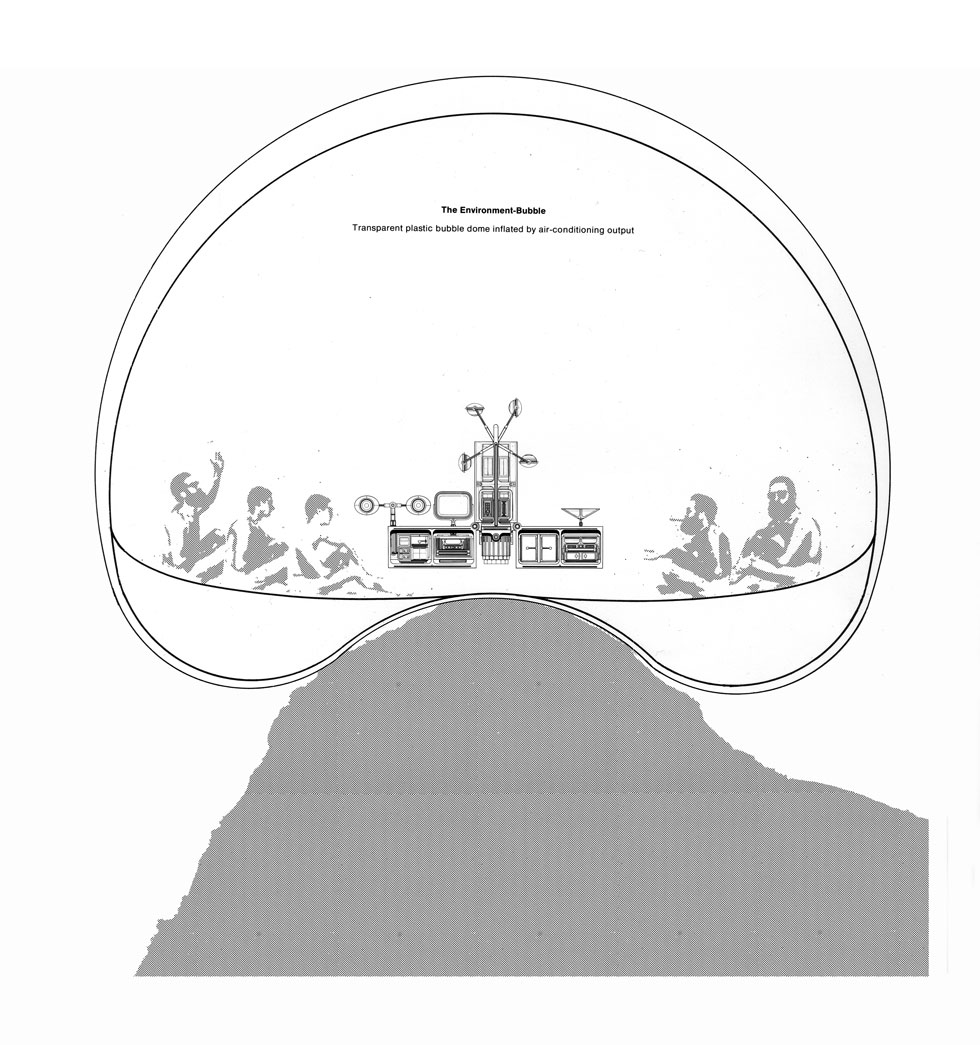

In many of the visions produced in the 1960s, including Fuller and Sadao’s Dome over Manhattan (1960), Banham and Dallegret’s Environment-Bubble (1965), or David Greene’s Living Pod (1966), among others, architecture is reduced to ‘bubble’, located in the thin membrane that establishes this threshold. Banham and Dallegret’s paradigmatic Environment-Bubble suggested that habitation was no longer a question of shelter, but rather, of conditioning, embracing the dematerialization of envelope and the augmentation of technology. Describing the “Standard-of-Living Package” which would anticipate a full eradication of the architectural envelope, Banham advocates that “to the man who has everything else, a standard‐of‐living package such as this could offer the ultimate goody ‐ the power to impose his will on any environment to which the package could be delivered; to enjoy the spatial freedom of the nomadic campfire without the smell, smoke, ashes and mess…”[2]

The image of Banham and Dallegret in the bubble, suggests an environment in service of comfort, with the eradication of all bodily encumbrances, including furniture and indeed clothes. Environment here is technologically controlled and is neutralized to remove, as Banham proposes, the messy realities required to maintain a conditioned environment. In a certain irony, the climatic and environmental differences between interior and exterior demarcated by the bubble remain abstract, as does the material reality of envelope, yet the architects knew exactly where the hi-fi stereo, television and speakers would go. In her essay “Ecology without the Oikos,” theorist Amy Kulper examines the relationship between morphology and ecology in Banham and Dallegret’s work, in contra-point to contemporary architectural practice. She argues that Banham brought an interest in thinking the ecological, evidenced in books such as Los Angeles: The Architecture of Fourt Ecologies (1971), where ecology is understood not as a science, but as “lived environment.”[3] Describing the Environment Bubble, Kulper writes the project “shifts architectural priorities from enclosure to building systems, from the monumental to the temporary…the Environment-Bubble embodies a diagram of architecture’s capitulation to technological imperatives, its envelope or skin reduced to a token gesture of enclosure, nearing invisibility, and quite literally stretched to both its material and disciplinary limit.”[4]

The Environment-Bubble: Transparent Plastic Bubble Dome Inflated by Air-Conditioning Output showing architecture as a “fit environment for human activities,” by François Dallegret, from Reyner Banham, “A Home Is Not a House,” Art in America (April 1965)

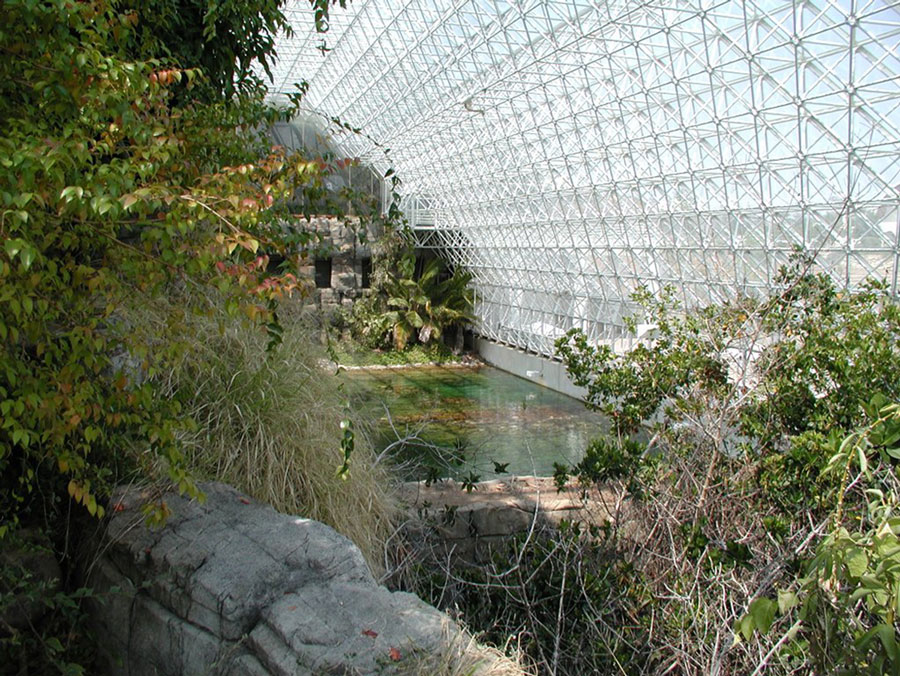

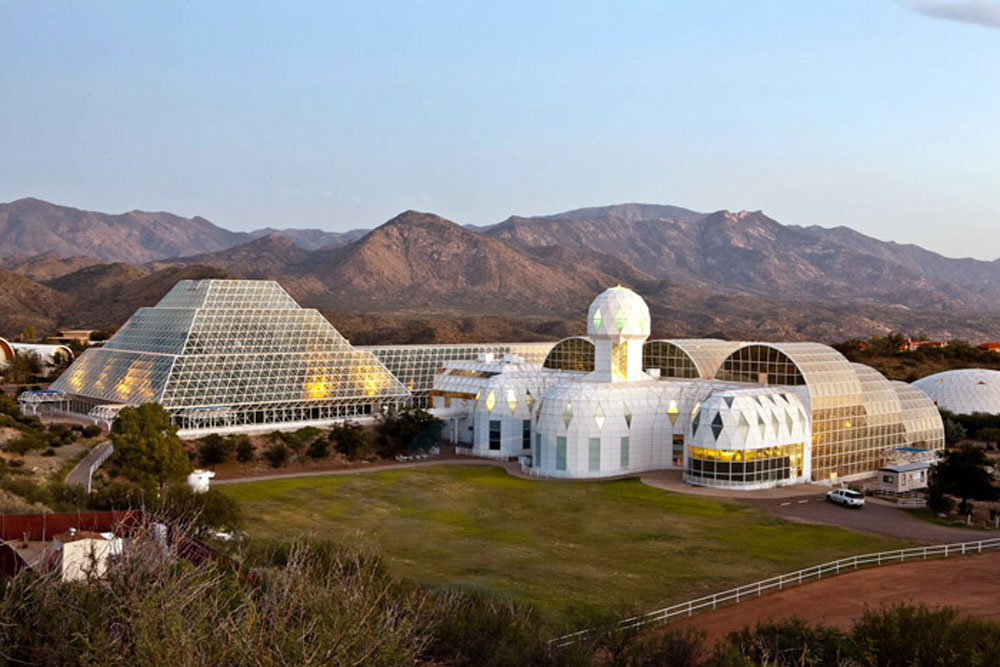

Operating at a much larger scale of environmental envelope, Fuller, in his unrealized Dome over Manhattan project, offered an articulate scenario for how the urban metabolism, the envelope’s structure, and the environmental systems of this visionary urban bubble might work. He describes methods for water management, indicates the need to heat the skin in order to shed snow and ice in the winter, and to manage solar gain in the summer, among many other issues.[5] Here, the ecological complexity and mechanics necessary for maintaining an isolated environment begin to be acknowledged. The ambition of mechanically producing and sustaining artificial environments reached its apogee in 1991’s Biosphere II experiment in Oracle, Arizona, which sought to reproduce—in a hermetically sealed spaceframe envelope—the web of interactions within life systems, including the provision of various ecological biomes, an agricultural zone and human living space. No exchange of air, moisture, or gas between the interior and exterior environments was permitted for the purposes of this grand experiment. However, ultimately, the complexities of humans, species, and ecologies cohabiting in a synthetic environment proved incompatible. In an ironic turn of events, the ambitious enterprise failed because ants chewed through the building caulking, causing multiple leaks in the structure, thus rendering the experiment void. “The unanticipated behaviors of the biotic life within the system threatened this clean separation of an independent container and the self-organized ecosystem it contained.”[6] What becomes evident across the range of bubbled environments is the struggle with, and in many cases disregard for, how to integrate biological matter; the unpredictability of plant and animal species was irreconcilable with the need to control environment. Even humans, in this context, are understood as technologically-dependent rather than biological beings.

Biosphere: a 1.3 hectare structure built to be an artificial, materially closed ecological system. Envisioned as a self-sustaining organization, it explored the web of interactions within living systems.

Many of these architecture bubble projects were being developed within the context of the 1960s and 70s environmental movement and the Cold War. Tacit in a number of the proposals was a defensive strategy against an exterior environment deemed to be potentially threatening or toxic, or at the very least, uncontrolled. This trait was evident in the later work of the California-based architecture and media collective known as Ant Farm. Ant Farm played off a “survivalist rhetoric and military tropes”[7] and their provocative installations were largely a response to the growing national nuclear weapons research program and an increasing awareness of environmental concerns. However, as theorist Felicity Scott argues, with its almost invisible skin, the bubble is evoked not [for] the promises of survival, but rather, to participate in a battle over the future of the environment. “Far from refusing technologies of control, or defending the discipline against their vicissitudes, Ant Farm situated their architecture within this very technological milieu.” [8] Peter Sloterdijk, in Terror from the Air, underscores the fundamental transformation that occurred in the twentieth century, when “the discovery of the ‘environment’ took place in the trenches of World War 1.”[9] Sloterdijk suggests that with the release of poison clouds upon enemy lines, Europeans created an ecologized war. In this new era of “atmoterrorism,” no protective envelope is possible; we are indissociably one with environment, and this very medium can be turned against us.[10] This awareness, alongside an ever-growing consciousness of climate change, renders our dependence and complicity with environment acute. Environment in the twenty-first century has becomes more extreme in its material, social, and political identity, raising the question of how architecture’s envelopes might respond, and what new roles might they take on.

Given the range of interpretations of the term environment, it is telling to review its multiple meanings. The term is understood as “the action or state of circumnavigating, encompassing, or surrounding something;” or “the physical surroundings or external conditions in general affecting the life, existence, or properties of a person, an organism or object.” Other meanings of the term embrace environment as “the social, political, or cultural circumstances in which a person lives, in particular as it affects behaviour, attitudes, etc.” or the overall physical, systematic, or logical structure (including operating system, software tools, interfaces) within which a computer or program can operate.[11] Also implied in the term is the notion of environment as a material entity; the air, moisture, and gases that sustain life. Embedded in each of these definitions is an idea of environment as a territory under the influence of a given force – be it political, technological, or ecological. Most architectural discussions on environment imply architecture at the scale of the bubble or singular spatial unit, architecture as envelope, intended to separate interior conditions from exterior surroundings. Yet the multiplicity of meanings outlined above suggest a more ambiguous and productive understanding of environment’s edges.

The Instrumentality of Environment

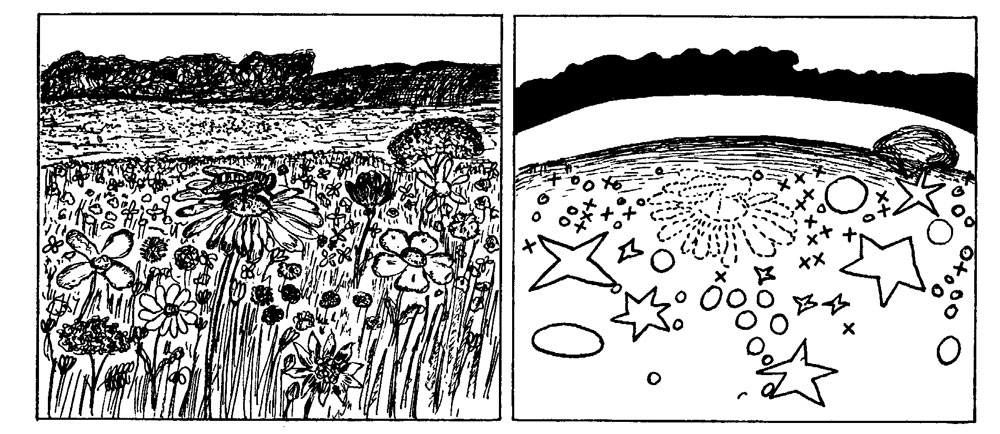

In the 1930s, German biologist and philosopher Jakob von Uexküll outlined the relationship between individual species and their physical surrounding in his treatise A Foray into the Worlds of Animals and Humans. Uexküll observed how living beings perceive their environments and articulated the difference between umgebung (surrounding) and umwelt (environment). Umgebung, he argues, consists of everything that is physically present in the territory of a species, while umwelt consists only of what is useful or instrumental to that species, or what Uexküll describes as a species’ “perceptual-life worlds.”[12] He argues that “an animal is not immersed in a given milieu but at best engages with certain features that are of significance to it, that counterpoint in some sense, with its own organs.”[13] The environment of the organism is precisely as complex as the organs of that organism. Uexküll suggests that each species has an environment bubble, albeit one bounded not by a physical limit, but rather an operational one, defined by the constituent elements required for survival. These elements serve as perceptual stimuli or cues to help define a species’ specific world within the surrounding. The umwelt of different organisms may overlap with one another; the relations between things expanding and meshing with one another in the intricate web of life. Embracing a comprehensive understanding of environments, Uexküll writes: “Nature conforms to a ‘super-mechanical principal’ that has no formative plan but that extends across all things, both organic and inorganic.”[14]

Umgebung and Umwelt of the honey bee. Umgebung or surroundings comprise all the elements present in the territory of a species; Unwelt or environment consists only of those elements that are instrumental.

From Bubbles to Webs

Extending from Uexküll’s suggestion of environments as webs of overlapping rather than isolated bubbles, the role of architecture in the production of environment—and the scale at which it might contribute—is challenged. In this scenario, architecture becomes but one milieu within a series of intersecting environments of people, species, plants, and machines. Architecture must work as a platform—an infrastructure or armature—that should be conceptually, if not literally, porous; able to allow movement of air, moisture, gases, materials, and species.

Only in the past few decades, has it been universally recognized that natural ecologies as deeply intertwined with human forces. Simultaneously, evolving metaphors embraced by the discipline of ecology have been shifting from a boundary and organism-based model to a systems-based one in which organisms and species are understood through energy flow or exchange maps.[15] Landscape architect Kristina Hill describes evolving paradigms of ecology, shifting towards a non-linear/equilibrium system, in which nature is driven by multi-directional change.[16]

Boundaries of Exchange

There is increasing acknowledgement of the role of temporal transformations within ecological systems, suggesting it is an unstable and changing set of dynamics. In order to understand ecological systems, flows, and exchanges, the boundaries of exchange must also be studied and conceptualized. Ecologists classify boundaries as having exogenous or endogenous origins, resulting, respectively, from processes outside or inside the system of boundaries or territories being studied.[17] The species and ecologies within the territory or zone might transform the boundary, as might exterior conditions such as wind, water currents, and species migration. These forces can maintain, augment, or weaken boundaries over time.

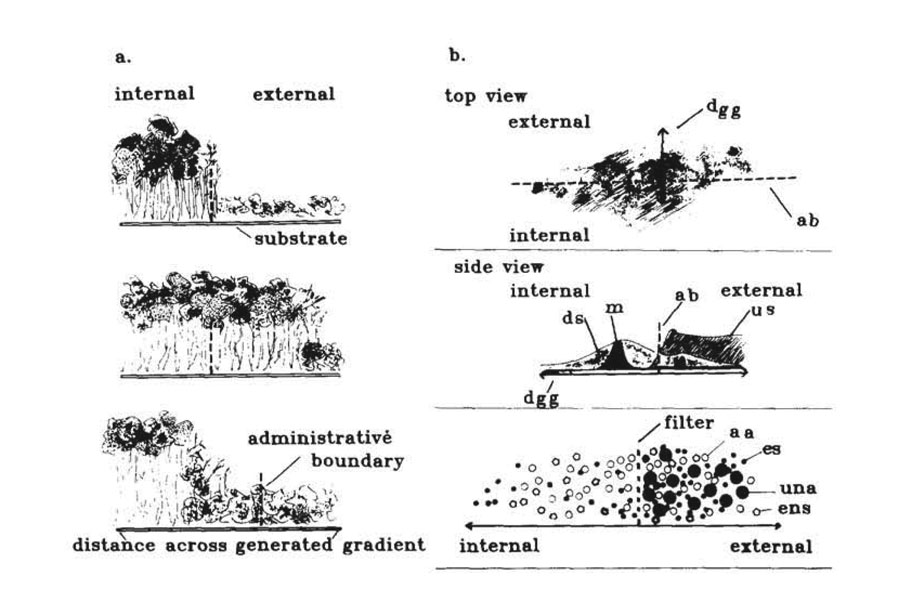

In the mid-1980s, Christine Schonewald-Cox and Jonathan Bayless analyzed ecological performance boundaries in relation to administrative demarcations, using National Parks as test cases. They proposed that the boundary of a reserve be viewed conceptually as a filter, that it is tied to biological forces as well as human culture, economics, and physical geography. They produced a series of planimetric and sectional studies documenting reserve boundary conditions, which can vary in nature and porosity along their edge. These boundaries are often defined by a “generated gradient or edge;”[18] a zone, with thickness that changes in abundance of species, resources and human activities, and that can move under the influence external pressures acting on the reserve. Schonewald-Cox and Bayless’ diagrammatic analyses demonstrate ecological boundaries as temporal, multiple, thickened, differentiated along their length, and mediating political, cultural, and ecological forces. Transferring such ecological models back to architectures and mediated environments raises questions of how envelopes and boundaries might operate under both interior and exterior forces—including flows of air, vehicles, human bodies, animal species, or plants.

Boundary Conditions: Diagram of three hypothetical generated edges relative to administrative boundaries (ab) Filter properties of administrative boundaries (ab).

Evolutionary Environments, Performative Boundaries

Many landscape architects, most notably Gilles Clement, have argued for the consideration of landscapes “in evolution” that are based on how species take hold, migrate, thrive, and fail within the immediate landscape and the extended ecological network.[19] To a large extent, this is in contrast with landscape architecture’s historically static aesthetic tendencies, in which a design, once implemented, is imagined to remain unchanged over time. In Clement’s model, design accommodates temporal change rather than enforcing predetermined end results, thus relinquishing control over outcomes.[20]

This design model is somewhat easier to envision within the medium of landscape architecture, which inherently works with dynamic processes of succession and evolution. Even so, Clement’s propositions were considered provocative when introduced in mid 1980s. Within any design field, relinquishing control is often at odds with aesthetic intent. However, similar discussions are now beginning to pervade architects’ design approaches, which respond to varying programmatic, economic or ecological demands. To embrace dynamic conceptions of environment, at the scale of buildings and urbanism, might suggest architectures able to evolve, transform, and weather; envelopes as surfaces of exchange, seeding or even cross-contaminating interior and exterior environments.

Most research into building envelopes has concentrated on furthering the comfort of its human inhabitants, or at best, to reduce energy loads. Other research has examined the transformation of buildings’ envelopes over time, albeit with a focus on aesthetic and performance questions.[21] While these ambitions are laudable, they maintain an anthropocentric bias and leave unchallenged the paradigm of architecture resisting environment rather than contributing to it. What if the boundaries and territories of buildings were able to sustain multiple species simultaneously–human, plant, and animal? If the envelope is understood as both acted upon but also acting on the exterior environment—impacting it, benefitting from it—architecture would need a far more reciprocal relationship with an extended environment.

Losing the Bubble

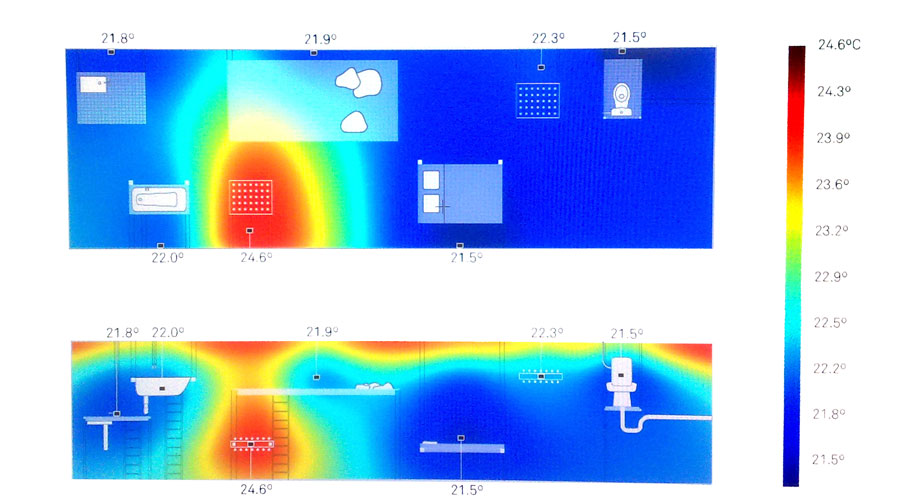

Over the past decade or more, the question of environment has been rekindled, in part due to the recovery of interest in Reyner Banham’s works and writings in contemporary architectural discourse, in particular his Architecture of the Well-Tempered Environment (1969). Banham’s metaphor of the campfire,[22] and subsequent projects such as his and Dallegret’s “Power-Membrane House” (1965) which removed the house enclosure entirely, opened up the potential for environment to be envisioned as zones—attractors of comfort or repellants of discomfort—in which boundaries overlap with other micro-environments. This position has been extended by practices such as Philippe Rahm, DeCostered Architectures, and Weathers, among others, continuing to reshape the discussion of environmental systems from the technical and performative to the spatial, programmatic, and experiential. Philippe Rahm argues for a “meteorological architecture” in which environment is understood as dynamic, defined by thermal strata and flows of air, governed by human behavior and needs, and demarcating zones of activity based on interior climates.[23] The work of such practices opens up new possibilities for architecture’s environment, rethinking the idea of spatially segregated and fully controlled environments defined by bubbles or envelopes. They also challenge the notion of undifferentiated comfort as a desired end goal, proposing instead a material understanding of environment that is tactile and tangible. While most of the work to date tends to focus on an immersive experiential sublime, there is the potential to consider such environments in relation to overlapping ecological, energetic, and atmospheric networks. Embracing the notion of micro-climates, at any scale, could enable new choreographies of people, plants, and animal species in a kind of soft geo-engineering of environments.

Domestic Astronomy. Functions and furnishings rise off the floor and stabilize at certain temperatures determined by the body, clothing and activity. Philippe Rahm architectes, Domestic astronomy, Louisiana Museum, Denmark, 2009.

Prototype for an apartment where one no longer occupies a surface, but an atmosphere. The proposal makes allowances for the physical differences in the distribution of temperature in a space, replacing a horizontal way of living with a vertical one where bodies can occupy different heat zones and different heights.

Materializing Environment

There is a growing body of work and architects looking at the under-belly of environments; what theorist David Gissen has provocatively termed “subnatures” or environments historically deemed undesirable by architecture, because they contravene our collective cultural notions of comfort, cleanliness, or control. These are environments constituted by insects, mold, dust, smoke, humidity, or toxicity, among others. Simultaneously, there is a growing interest to understand architecture’s environments as substrates for both human and animal species.[24] In these scenarios, architecture’s environments become the bio-physical substrate for plant and animal species, an armature both for natural processes and for human inhabitation. How human and animal species cohabit, the degree of spatial intertwinement, and the mutualistic benefits of such cohabitation and spatial co-speciation offers new design challenges. Architecture could become the armature or prosthetic for symbiotic environments that embrace the natural and the technologically enhanced, the stable and the dynamic. The true potential of architecture participating in the production of environment-webs will in fact materialize when architects shift the discussion from environments to ecologies, and embrace conditions of instability and variability.

Understanding architecture not only in the service of humans, but also species, is part of a larger discourse on post-humanism permeating the humanities and increasingly, architecture. In What is Posthumanism, theorist Cary Wolfe explains that post-humanism questions the role and hierarchy of the human in relation to ecological, evolutionary, or technological paradigms, problematizing the relationship between anthropocentrism and speciesism, arguing that “the environment is thus different, indeed sometimes radically different, for different life-forms.”

From Environment to Ecologies

Fifty years ago Reyner Banham advocated for architecture to be pure environment, embracing an erasure of the envelope in favor of technology as producer of environment. Describing the Power-Membrane House—a project that was an extension of the Environment-Bubble—Banham wrote that “the basic proposition is simply that the power‐membrane should blow down a curtain of warmed/cooled/conditioned air around the perimeter of the windward side of the unhouse, and leave the surrounding weather to waft it through the living space.”[25] Such a proposition, if seriously embraced, would compel designers to consider the full complexity of such an interaction—the nature of the boundaries, and the potential of such interaction within a much broader understandings of environment.

Such an approach advocates for a shift away from technologically deterministic conceptions of architecture’s envelopes, privileging instead a more radical and extreme notion of enclosure and boundary; as interface of exchange between a vast number of forces. It might even be conceived of as an environment in its own right—a thickened, ecologically active surface, capable of producing ecological gradient conditions which could overlap with those of other species—whether plant or animal—for mutualistic purposes.

Such models of envelope and boundary, if embraced, would force inhabitants of architecture to consider interaction with the full physical materiality of an environment. It does not represent a call for bio-memetic models of architecture, in which structures emulate traits of species, but rather that buildings and urbanism embrace their role as habitat and producer of umwelts within competing webs of species and ecologies. Architecture and urbanism might at certain times be producers and at other times be consumers of environments and the resources within it. Architecture and envelope would necessarily be dynamic—required to transform, evolve, or decay over time—acknowledging its inherent environment-webs.