Construction on the Seagram Building commenced with the completion of the Montana’s demolition in January 1956. The spring of that year was occupied by excavation operations that would soon accommodate the building’s massive steel and concrete footings, a significant portion of the building’s subterranean mechanical plant, and parking for one hundred vehicles. By June, the concrete retaining walls were filled by steel framing and formed the base of the tower and its future plaza, used during construction as a construction yard. By the end of summer 1956, the steel framing rose several stories above grade and was soon followed by board-formed concrete that encased the steel structure. By the fall, steel brackets methodically mounted to steel and concrete perimeter frame of the Seagram Building began to accept the longest of the famous I-beam extrusions that are the structure of its envelope. Contrary to many accounts of the Seagram Building, these I-beams are not steel, nor even bronze. What is referred to as the “bronze” envelope of the Seagram Building is actually a brass alloy oiled and oxidized to look like bronze.

By December 1956, the steel framing of the Seagram Tower was complete, soon followed by the completion of its concrete encasement. By the spring of 1957, the “bronze” envelope was complete and half of the tower was enclosed with glass. The Seagram Company would occupy six floors of the building beginning in late 1957, followed by the remaining tenants in 1958.

This history of construction on 375 Park Avenue—from its first building in 1857 through the completion of the Seagram Building in 1957 and its ongoing maintenance and renovations—reflects a typical pattern and cycle of urban metabolism.[1] Buildings—along with the motivations, money, materials, and energy that engender them—appear and disappear in pulses of construction and deconstruction as cities like New York City evolve. The financial logic that drives this process of building and un-building—what Thorstein Veblen called “planned obsolescence”—raises environmental questions and becomes one way to transition this construction history study into a more specific construction ecology study. Suffice to say that the financial logic of speculative real estate development does not incorporate what Odum described as the “real wealth” of the materials and energy contained in the Steinway & Sons Piano Forte Factory, the Montana, or the Seagram Building. Rather, the abstraction of these terrestrial entities into monetary values and their inherent externalities is ultimately demonstrative of violent abstraction. The economic valuation of these terrestrials is violent in terms not only of its cycles of demolition, but more broadly of the slow violence of far-flung environmental degradation and the slow violence of social and political degradation that are attached to these processes of building and un-building.

Mass, Massing, and Masses

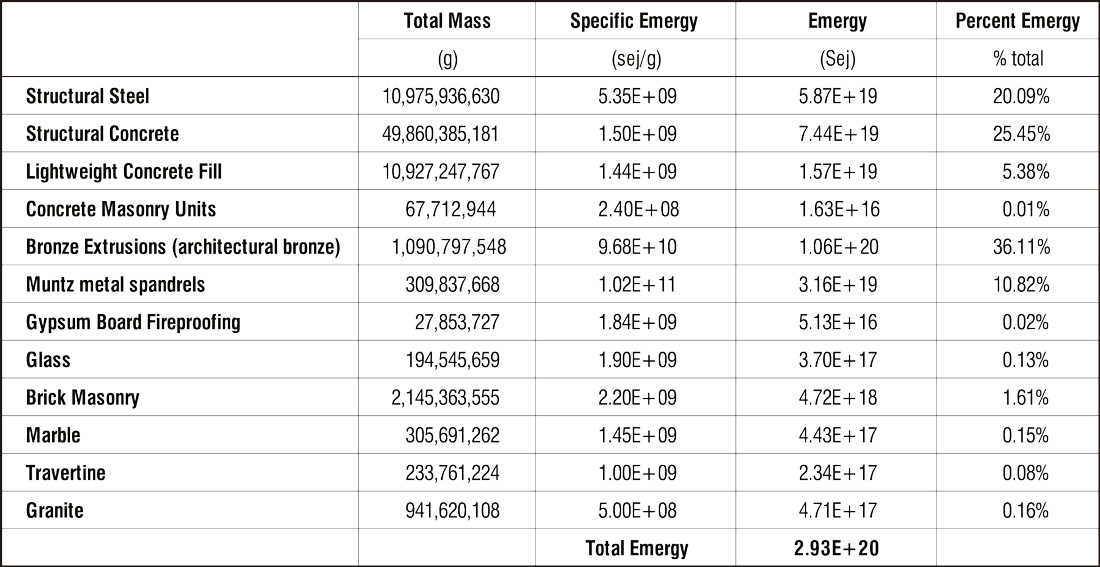

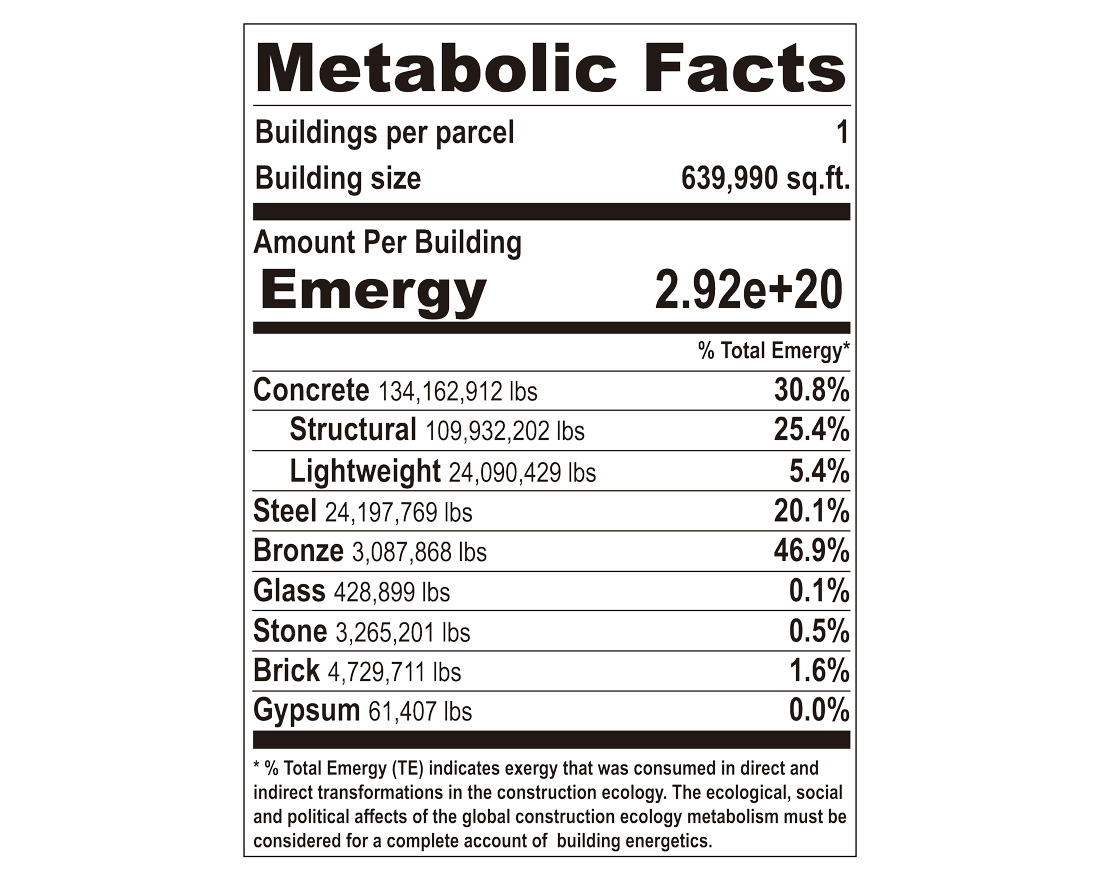

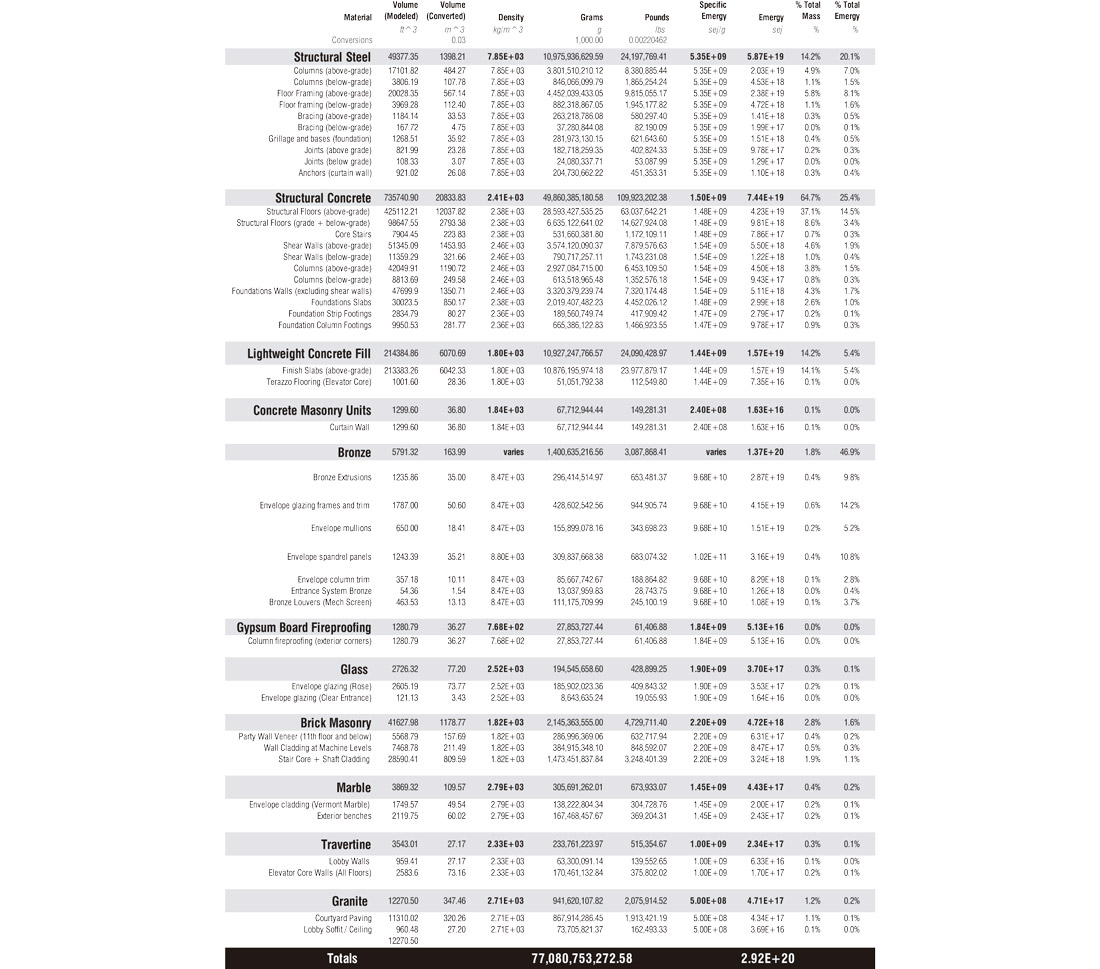

The remainder of this chapter submits the Seagram Building’s construction to a short-form emergy analysis. Here I use emergy as a type of scale analysis, as described earlier, to explicate some key relationships about the material and energetic basis of the Seagram Building. I do this in terms of relative orders of magnitude. In a related book, Empire, State & Building, I compared the successive states of a plot of land in ecological terms. Given the similar types of construction and cycles of building and demolition, the emergy analysis of urban morphology would likely yield similar results. Here, the method is related but the outcome is distinct. The focus of this book is instead on one phase of building and un-building this site—the Seagram Building—so as to dig deeper into its terrestrial basis.

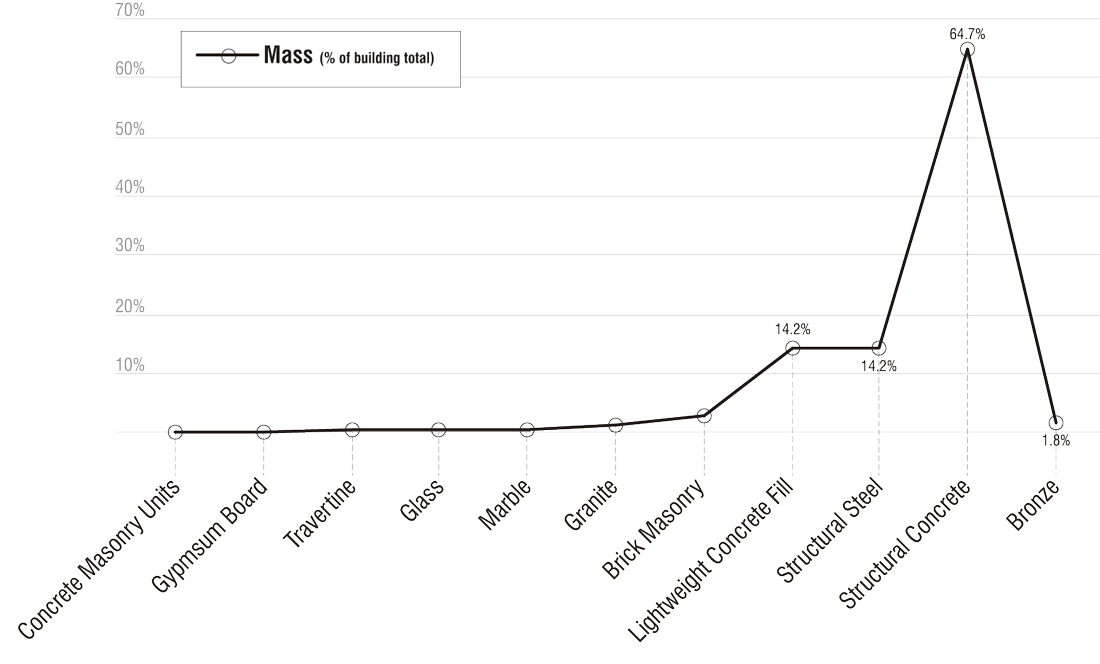

The procedure for this phase of analysis is straightforward: model every component of the building’s structure and enclosure, determine the volume of material in the building, and, based on that material’s density, derive the mass of each material in the systems. This establishes a simple initial indicator that can help guide which material systems warrant further analysis. Much evidence and assessment of the Seagram Building in this book was based on an intricate model of the Seagram Building construction, which modeled every component of its structure and its enclosure. This model was based on a mixture of archival materials, such as construction documents and construction photographs, as well as on-site documentation and observation.

This initial focus on mass soon reveals other relationships that are important to a construction ecology: the relationship between mass, massing, and the masses. In other words, by modeling the massing of a building (its physical volumetric profile), specifically through a meticulous account of the mass of material that structure the volume of that building, a relationship between weight and occupiable volume is established. In the aforementioned study on the Empire State Building, I showed how it weighed nominally the same as the pre-existing Waldorf Astoria Hotel.[2] The tower, though, hosts about 20,000 people, an order of magnitude more than the hotel. So even mass can serve as a crude indicator of the ecological efficacy of different architectures, even though they use a similar amount of material.

In the case of the Seagram Building, 79% of the tower’s mass is concrete (structural concrete and lightweight concrete fill). We rarely construe the Seagram Building as a concrete building, but by mass it is predominantly so. We might more readily assume that the Seagram is a steel building, which is indeed the physical substrate of its primary trabeated structural system, yet this only accounts for 14% of its mass. The architectural identity of the Seagram Building is typically associated with its “bronze” and glass enclosure, but these materials together constitute only about 2% of the building by weight.

To measure and weigh the building is no simple task in either procedure or outcome. In terms of procedure, determining the as-built conditions as they invariably differ from the construction documents imposes many lively debates and challenges. In terms of outcome, though, the complexity that can emerge from the apparent simplicity of measuring, inventorying, and surveying mass is conveyed best by Fernand Braudel who—having written a three-volume, two-thousand-page history of capitalism including The Structures of Everyday Life, The Wheels of Commerce, and The Perspective of the World—observed:

It would be best of all if we could evaluate the entire mass of urban systems, estimate their overall weight, still taking as our base that minimum limit, the articulation between town and countryside. Overall figures would tell us more than individual statistics: to be able to place on one side of the scales all the towns, and on the other the total population of an empire, a nation, or an economic region, then to calculate their relationship, would enable us to give a fairly reliable estimate of the social and economic structures of the unit under observation. [3]

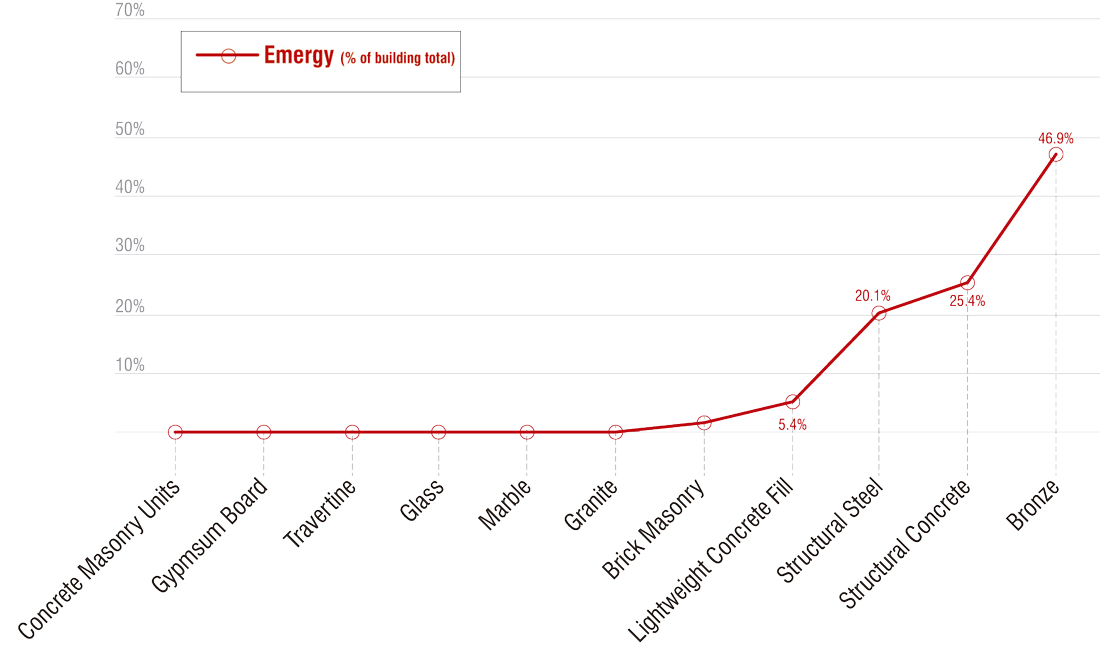

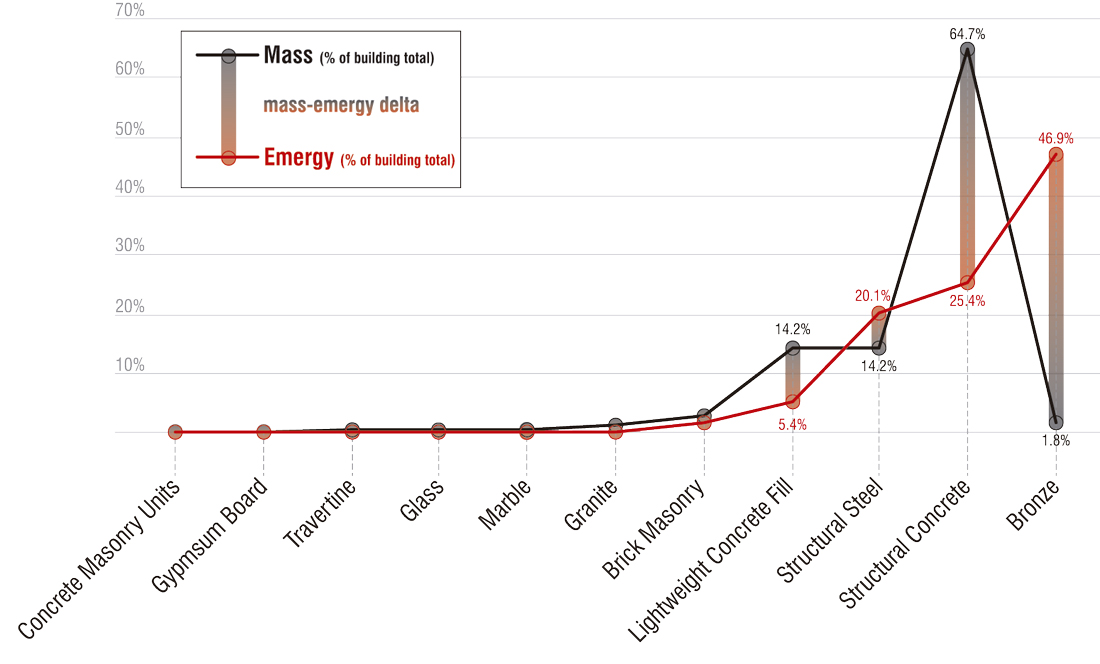

The basic extensive measure of the Seagram Building—the evaluation of its mass—is an important first step toward other, deeper forms of analysis such at the social, economic, and ecological articulation of core and periphery dynamics, as Braudel suggests. It is a necessary step to other, less reductive types of analysis. Once mass and cubic volume values are established for each material, emergetic indices can be applied to the material quantities to provide more insight about the bio-geophysical resources that are accumulated in the Seagram Building. At this stage of the analysis, we can look at the building as an unusually articulate pile of emergy, an emergetic artifact. The resulting statistically significant materials in terms of emergy are concrete, steel, and brass.

That concrete and steel, which together comprise 84% of the building’s mass, are significant emergy loads in the construction ecology is perhaps not surprising. Together the bulk materials used for the concrete and steel structure of the tower constitute about 51% of the emergy accumulated in the building. That brass, which is less than 2% of the building mass, constitutes about 47% of the remaining building emergy is a more surprising insight into the ecological dynamics of the building.

How the mass and emergy curves in these charts converge or diverge is also of interest and provides some insight. In some of the bulk materials, such as concrete, the mass exceeds the emergy of the material system. This reflects the readily available source and relatively low-processing loads of that material’s bulk, such as its aggregates. In the case of metallic materials, such as steel and brass, the relative emergy exceeds the weight. This indicates that far more concentrated world-systems resources and processes are embedded in the metallic than the bulk ceramics.

Even these preliminary emergy accounts help frame which aspects of the world-systems of the Seagram Building warrant further analysis in terms of unequal ecological exchanges. The mass-emergy ratio of the bronze, for instance, indicates that the production of the building material from its telluric source requires significant inputs on energy, labor, and likely transportation. The more steps necessary for the production materials equate to more world-systems exchanges, which thus opens more opportunities for uneven and asymmetrical exchanges in the world-systems of that material production.

In other words, high-emergy materials have a greater impact on the system. This impact could possibly be positive if designed properly, that is, if nature and society are organized in ways that reinforce rather degrade one another. It is important to note in this regard, that high-emergy materials and processes are not inherently negative or to be avoided outright, per se. In modernity under capitalism, the unconsidered and “unintended” impacts of high emergy materials tend to have negative impacts. What is essential is to acknowledge that higher concentrations of emergy are, if anything, an indicator of greater capacity to impact a system through intake and feedback design. More emergy means more social and ecological opportunity affect a system. As a high-emergy artifact, building as a process of planetary urbanization is replete with opportunity to reinforce and amplify, rather than simply degrade, a construction ecology.

Through this short-form emergy artifact analysis, we begin to see which materials are of consequence ecologically, and which are suggestive of more intricate social, though no less ecologically consequential, world-systems dynamics. In the case of the Seagram Building, the structure and enclosure are significant in emergetic terms. The oiled brass is of particular interest given its unusual emergy-mass ratio. Since this material system is also of immediate architectural significance in historical accounts of the building, the ecological and social contingencies of the brass is the salient material system studied in this book.

But other materials too, as we will see in the second part of this book, are of terrestrial and architectural significance. The glass is the necessary counter-part of the building’s brass enclosure. In terms of both mass and emergy, the glass is statistically insignificant. However, as we will see, the social and economic consequence of the glass specified for this building is significant given its particularities and their social and economic implications—not so much for the Seagram Building but rather for the company that manufactured the glass. Other materials, such as the granite pavers in the Seagram plaza and lobby, are likewise statistically insignificant in terms of mass and emergy but provide some insight into somewhat minor world-systems dynamics of building and construction ecology that together better describe terrestrial architectures. Together with the brass envelope, the pavers offer insight into the ongoing maintenance of building as ecological and word-systems dynamic.

To reiterate, the use of emergy analysis here is not deterministic or reductionist, and it does not aim for “optimization” as its end. Instead, it is used as an indicator, a suggestive index of which terrestrial processes associated with the architecture of the Seagram Building warrant further analysis and the likely type of analysis. With this preliminary hierarchization of the Seagram Building’s construction ecology, we can shift to other forms of world-systems analysis which will help further characterize the Seagram Building as a terrestrial entity. In the next section of the book, the hierarchy of materials established in this chapter will guide a set of concepts and methods which will help explicate the social and political dimensions of the Seagram Building through a set of “technofossils” that will better characterize the terrestrial details of the Seagram Building.