A dialogue on our responsibility in dismantling anti-Black design curricula and spaces in architectural education. The idea for this dialogue occurred after observing that the responsibility and appeals to respond to the institutional racial inequities and discrimination experienced by Black students in the academy disproportionally fell on one of us, who identifies as a person of color. By sharing our identity and perspective as a person who identifies as Latinx or white cisgender male in the same writing space, we’re establishing a framework for conversations that acknowledge privilege in parallel to those that have been historically marginalized. To have a conversation on curricular changes towards equity, we advocate that it must happen in dialogue with those groups that are in constant threat of erasure.

The hammock was used by up to thirty people at a time. (Hansy Better Barraza, The Big Hammock, 2010. Photo by John Horner.)

AP We are in a moment of significant historical change. At the moment, the pandemic is raging, and we are actively participating in the BLM movement here in the USA. You identify as an anti-racist Latinx architect (among many other layers of identity—mother, daughter, niece, spouse, citizen, advocate, mentor, activist, friend, educator, colleague, and so on). All these facets construct and define your personal identity, they also inform how you approach practicing and teaching. One’s values may reside at the intersection of personal identity, moral imperatives, cultural beliefs, and what one discerns as being good for our society. How do you identify and/or define your values with the architectural projects you initiate or take on?

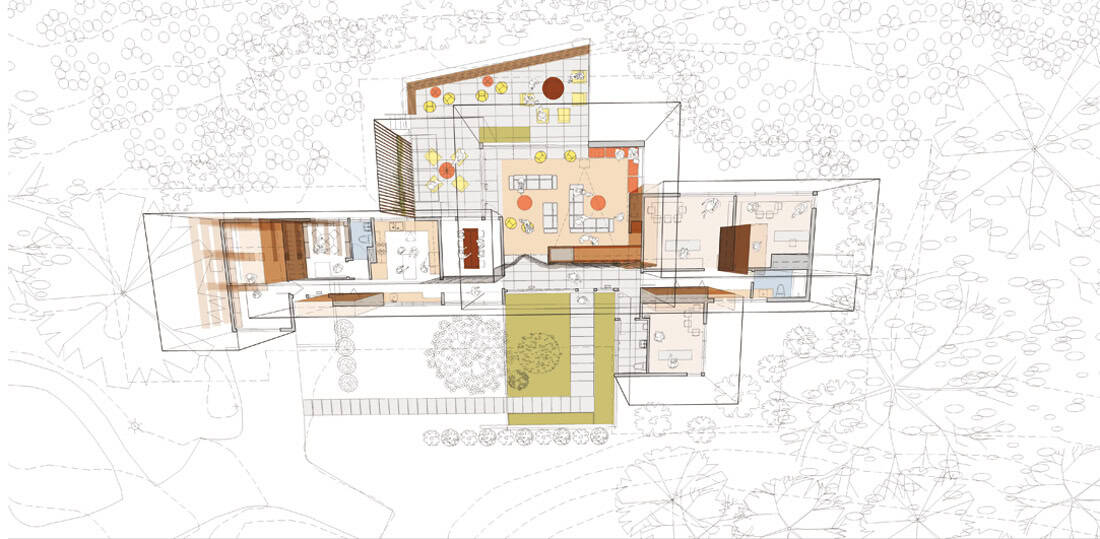

Exploded axonometric drawing showing the new uses of this former multifamily residence, including culinary, fine arts, music, maker spaces, seminar, and performance areas. (Studio Luz Architects, Sociedad Latina, Roxbury, Massachusetts, 2016–2020.)

HBB I’m Colombian, a descendant of three different races: black, indigenous, and white. In the United States, I identify as an immigrant Latinx. When I want to emphasize gender, I say I am Latina. I live in two worlds, between Colombia and the USA. I’m connected to these two places through the internet. In practice, I try to link the global to the local where culture, identity, ethnicity, and race could be explored, enhanced, or even celebrated.

Our cultural experiences and our identity shape how we think and produce architecture. This is our mission and the value we bring to every architectural project we take on at Studio Luz.

For example, in The Big Hammock, sited on the Greenway in Boston, the object provided a space in the city that challenged boundaries, avoided classification of national identity, and created community. The Big Hammock intrinsically takes the form of its occupants—their bodies, their postures, their actions and interactions—its ever-changing form was the result of shared experiences. As people occupy the hammock’s surface, they negotiate positions and balance the forces in the hammock.

People are required to engage, to maintain balance or gently swing the structure with a few choreographed moves, we were excited to see that many conversations were started. The Big Hammock was a woven structure that used rope manufactured from recycled milk bottles, the colors of the rope were selected to imbue the surface with multiple associations, such that people with various cultural heritages may relate to the woven surface. For example, Colombians thought the hammock was representing the flag of their country, Americans thought the American flag was projected, but looking closely at the color sequence, it doesn’t fit either category. It was in-between sites that reflected the spaces I’ve occupied being Colombian raised in America. Shared experiences form common references.

As a white cisgender male, how will you undo the white supremacy that has dominated design pedagogy?

View of renovated outdoor terrace and social lounge. (Studio Luz Architects, Terrace, Acorns House, Wellesley, Massachusetts, 2016. Photo by John Horner.)

AP I strive to illuminate my personal “blind spots” and root them out of the course content. I strive to create learning experiences for students that reflect their own values, sense of personal identity, and discuss how their specific viewpoints inform decision making. This rooting out must be expanded to include all aspects of the architectural curriculum, as well as the design studio programs. New, anti-racist forms of knowledge must be created that fundamentally inform the discipline of architecture. As a white male, I recognize my privileged position; I am very conscious of the words and images used in the way I teach. To even begin to undo white supremacy, we must acknowledge that it exists and that racism is informing architecture today. We must strive to understand how the past informs the present, and that white supremacy has eclipsed the histories of Black people in the built environment through policy, processes, and cultural expression. I am not ignoring the many other cultures and identities suppressed through white supremacist structures.

At this historical moment, it is important to frame this conversation in the context of BLM. This is how change begins to come about. We must strive to include the work of Black architects into all coursework. Learning from the history and contributions of Black people to the culture, spaces, and traditions of place making in the United States is a critical first step. This step will allow for other narratives to emerge, as we must strive to expand the frame of reference. There must be an amplification of Black voices within the academic environment as a whole. I have a moral and ethical responsibility to provide students with examples that resonate with their lived experiences and expand upon their knowledge.

Design is a process, a process informed by decision-making. The factors that influence decisions must be projected through an anti-racist lens. Design processes must include more Black voices to influence decisions if we want to produce changes in power. As a white educator and architect, as I just stated, I will strive to amplify the Black voices of those that have been silenced and overlooked through the process of design. There needs to be a paradigm shift in design decision-making that strives for equity and resilience. Academically, we must continue to seed our syllabi, discussions, workshops, and assignments with the work of Black people. The contributions of Black people in informing the built environment must become core knowledge to promote activism. I say this in consideration of Ibram X. Kendi’s words “Critiquing racism is not activism. Changing minds is not activism. An activist produces power and policy change, not mental change. If a person has no record of power or policy change, then that person is not an activist.”[1]

In professional practice, as a white male, I need to know when to step aside and how to build awareness. In our practice, Hansy, as a Latinx woman, it is important that you are the lead for much of what we do, for providing direction for the firm. In the Big Hammock project, you had a clear objective to create a public work that amplifies the social implications of objects in space. We currently have a partnership with a Black artist, Marlon Forrester, designing artworks for a playground. In this project I serve as a trusted collaborator. My voice will be part of the chorus on that project as well. Stepping aside can be an act of social justice.

Perspective overview showing the new spatial overlaps and uses. (Studio Luz Architects, Acorns House, Wellesley, Massachusetts, 2016.)

HBB Architecture is an instrument of power. The profession has had a role in translating abstract ideas into commodities (buildings) that create monetary value. In a capitalist system, this is the goal. Can architecture take on the role in establishing new power structures that deliver equity to communities of color and provide opportunities for wealth creation?

AP I think we need to ask who wields architecture’s social and political power, how do we frame architecture as a cultural product over a commodity? It is often not the architects. We also need to ask who benefits from the architectural endeavor as a process and a construct. Who is excluded from the process and the construct? With the exception of very few, I am not convinced that architects have much power over who gets to build what; it is often driven by forces external to the profession itself. We are entrusted with the health and safety of those who inhabit the buildings we design. For architecture to establish new power structures, there needs to be radical new ways of creating opportunity. If architects can engage in local government, serve on community boards, lead community driven projects, innovate new models of design/build practices, and be better at educating developers on the value of and future impacts of the buildings being produced, then I think they can start to wield the power of architecture as a cultural endeavor.

What do you intend to do more of in to order to develop and promote the power of architecture as a cultural endeavor in your work?

Various layers of the entry hall can be moved to reveal or conceal the meetings areas. (Studio Luz Architects, Entry Hall, Acorns House, Wellesley, Massachusetts, 2016. Photo by John Horner.)

HBB “What’s needed today is a paradigm shift from valuing objects as an economic investment to a new moral design capitalism that serves society.”[2] This quote was relayed to me by Ted Landsmark, the former President of the Boston Architectural College and has stuck in my mind. The architecture that emerges from a shared experience and exchange has motivated our office in finding modes of practice that are alternative to the traditional model. To serve a diverse society and to do creative work, we’ve had to take on the role of initiator, fundraiser, implementer, and at times operator to see the project through its concept phase to construction.

Alternatively, projects that have emerged from a moral design capital begin from a bottom’s up approach. We need more of this. The renovation of Acorns House, a historic building on Wellesley College’s campus, was the result of a student driven initiative—a demand to house Asian, Latinx, and LGBTQ Advising within the Office of Intercultural Education. The Acorns House is a political project. It was part of a larger mission from the institution to create a network of multicultural centers that included the existing Harambee House, focused on students of African descent, and the Slater House, which caters to the international student population. The primary challenge for Studio Luz was to design a space that could accommodate multiple cultures, a multi-cultural center that reflected multiple, intersecting identities. The Acorns project is an example of a project driven by a political will that valued a world that was interconnected and multidimensional, bringing together people with different histories and cultural backgrounds.

What I would like to see more is an inversion of the traditional client and architect power relationship by envisioning the client as part of the end user group and the architect as initiator of a project, so that we might ultimately have control in creatively finding solutions to the needs of a community. Working with Sociedad Latina—a nonprofit organization founded in 1968 that caters to at-risk Latino youth in Roxbury and whose mission is to end the destructive cycle of poverty—has been an eye-opening experience in that our firm has given agency to an organization by providing them with a feasibility study and design services so that they might own their building and resist the pressures of gentrification. The client was driven by a moral imperative of stabilizing the organization for the next fifty years. In addition to the paradigm shift of the developer model of profit-driven projects, I will continue to advocate for design commissions that go directly to support BIPOC-led firms. This is key to the survival and longevity of these firms in the re-imagination of the equitable city we long for.