Towards a new community-led governance approach, integrating the global into the mundane – and why design matters.

Contemporary Africa is undergoing a rapid evolution, with several African nations experiencing the highest global rates of urbanization. Nigeria, ‘The Giant of Africa’, is no exception and has recently surpassed South Africa as the continent’s largest economy. Along with historical challenges the country has faced, such as corruption and lack of governmental transparency, rapid urbanization brings a new set of issues to the fore.

This paper explores alternative governance models in developing nations against the backdrop of rapid urbanization and the growth of informal structures. Roughly two-third of Africa’s urban population live in informal, over-crowded settlements, and two-fifths live below the poverty line. Informal employment accounts for roughly 60 percent of urban jobs. This paper examines potential models and solutions to address some of these urgent issues, stressing the importance of integrating the ‘global’ with the ‘mundane’. The paper focuses on the low-income community of Makoko in Lagos, Nigeria, as a case study. It presents alternative community-led sustainable approaches to urban governance, while drawing attention to the interface between the built environment and governance, and highlighting the role of design in shaping social infrastructure. It further suggests that formal/informal and top-down/bottom-up governance should come together to tackle urban challenges such as the lack of basic infrastructure and services, the lack of steady income and the adaption to climate change.

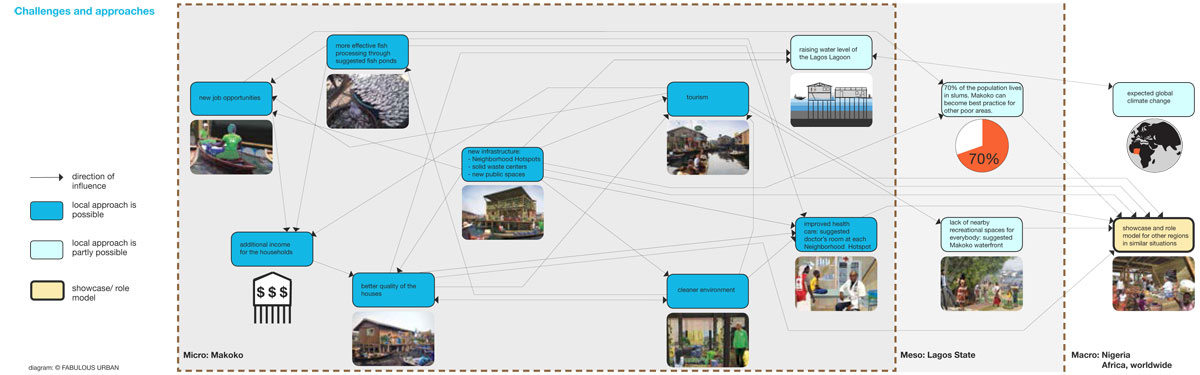

Challenges & Approaches

Makoko

The community of Makoko is a prime example of disproportionate growth amid rapid urbanization in the developing world. Makoko is a waterfront community in the heart of the city which lies along the Lagos Lagoon. Historically a fishing community predating the establishment of Lagos State, Makoko has devolved into an urban slum over the years due to rural-urban migration and poorly governed development. It is a culturally diverse community with six main sub-communities, four main ethnic groups, three practiced religions and over five spoken languages, and despite the surrounding urbanization, traditional governance structures and rulers (baales) still exert an enormous amount of influence within the community. Its economic structure revolves around the use of water for fishing, boat making and craft. The community relies on basic traditional technology in the processing and production of its goods, contributing to slow economic growth.

In Makoko, 40% of the population live on less than USD 1.25 per day. This is reflected by the figures on sub-Saharan Africa, where 43% of the urban population live below the poverty line. Additionally, the discourse in many developing regions places too much emphasis on economic growth, resulting in a fixation on bare numbers and figures instead of economic development, which takes the distribution of wealth into account. The latter would benefit a wide spectrum of the population, while a single-minded focus on GDP growth and international investment may result in even larger income inequalities, benefitting an elite minority. Even the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund agree in their latest report that job creation and poverty reduction require much more than just economic growth. There are an increasing number of extremely rich Africans. While such individual success stories are impressive, the vast majority, even in Lagos’ booming economy live partially in extreme poverty.

With a population of approximately 50,000, Makoko is one of the largest low-income communities in Lagos. The World Bank, through the Lagos Metropolitan Development and Governance Project (LMDGP) intended to invest $40.9 million in upgrading nine selected slum neighborhoods, including Makoko. However, the World Bank recently stopped the funding, and LMDGP was dissolved amid accusations that the project failed to properly apply the funding for its intended purposes. Additionally, the state government commenced the demolition of some of the ‘illegal’ structures in Makoko in 2012 and in Badia in 2013 in preparation for new development. No accommodation was made for the resettlement or compensation of community members, which led to public backlash and eventually a court injunction to cease the demolitions. The resultant situation is one of deep-seated distrust, with the local citizens and informal institutions pitted firmly against the government and formal structures. The state of governance in Makoko typifies the disconnect that exists between formal/top-down government institutions and local citizens.

The state of governance in Makoko typifies the disconnect that exists between formal/top-down government institutions and local citizens. The case of the LMDGP’s misappropriated funds shows that international agencies and development banks need to rethink how they relate to the urban poor and organizations charged with engaging them. In most cases, official aid agencies and development banks do not implement initiatives on the ground, instead funding others to do so—and they are only as effective as the local institutions they fund. If the funded central or local governments have no relationships with, or accountability to, the local citizens, these international organizations—no matter how honest their intentions—reinforce undemocratic structures. The citizens of low-income communities are often acutely aware of what is required to improve their living conditions, generally needing relatively little funding. There is a need for local governments and institutions that listen and respond to local communities (particularly the urban poor), working in collaboration with them to develop appropriate solutions (Satterthwaite, 2011, 2013; Hoelzel, 2013; Fabulous Urban, 2014; Akinsete, et al. 2014).

Neighborhood Management as a Model for Community-based Governance

In the new context of dynamic and rapidly evolving urban centres, community engagement and citizen participation are an essential component of urban governance models which are closer to the ground, more flexible and more responsive to local needs. Following the backlash resulting from the Makoko demolitions and the subsequent injunction, the state government expressed a willingness to consider alternative development plans for the area 2015 LSE Africa Summit Special Issue proposed by the community. Lagos-based NGO the Social and Economic Rights Action Centre (SERAC) brought together a multi-national and multi-disciplinary team mandated to work with the community to develop a ‘Sustainable Regeneration Plan’.

Exploring alternative governance structures was a key element of the Makoko-Iwaya Regeneration Plan. The team aspired towards the integration of top-down and bottom-up community development, producing an alternative regeneration plan addressing the concerns of the community while meeting the ambitions of the state government. The results of an in-depth situational and needs analysis conducted as part of the process indicated that apart from basic infrastructure (such as sanitation, healthcare, housing, energy and education), community empowerment was identified as a priority area of concern. The team looked towards existing models of decentralized governance and development, exploring adaptations for the local context. Neighborhood management was identified as a grassroots governance approach embedded within the community that could inform the development of a community-led governance model in Makoko.

Neighborhood management aims to deliver urban governance at the local level, considering a holistic view of an area as opposed to along various strands. Originally developed in the UK as a means of delivering urban regeneration, this place-based approach seeks to ‘narrow the gap’ between deprived communities and affluent areas (CLG, 2008), an issue particularly relevant in Lagos, where the gap between the elite and the urban poor is extremely wide. The UK Department for Communities and Local Government (CLG) describes the process as bringing together ‘an alliance of three forces—representatives of the local community (including councillors), representatives of local service providers and a small professional team led by the Neighborhood Manager to facilitate change’ (CLG, 2008, p.18). Essentially, neighborhood management seeks to utilize a grassroots method of regeneration delivery where local services are pooled and brought into alignment with local community needs, thus making them more responsive. Neighborhood management covers a wide scope of activities: from the work of estate wardens, caretakers and housing managers, to strategic planning and local governance, addressing issues including resident satisfaction and involvement, education, health, security, housing and employment (Power and Bergin, 1999; Brown, 2002). The objective of neighborhood management is to create efficient service delivery within a particular geographic boundary, tailored to address the unique issues faced by its local community, thereby improving citizens’ quality of life. This highlights how the neighborhood management model lends itself to the context of most developing nations where service delivery tends to operate on a micro-management level via informal structures.

The day-to-day operational process is overseen by a neighborhood manager, who focuses on the ‘totality of place’ working in partnership with both the community and service providers to tackle local problems from the residents’ perspective. The Social Exclusion Unit (SEU) outlines a basic model (see the information below) for neighborhood management, which sets out five key features of neighborhood management and four main tools for successful delivery. This model has formed the basis of the development of different place-based initiatives in the UK, such as the Pathfinder Program and New Deal for Communities.

Neighborhood Management

Features

Someone with overall responsibility at the neighborhood level for managing the renewal process

Community involvement and leadership

A systematic, planned approach to tackling local problems

Effective delivery mechanisms

The tools to get this done

Tools

Agreements with service providers

Devolved service delivery and purchasing

Pressure on agencies and government

Special resources on enabling and cross-cutting activities

Translating Neighborhoods Management to Developing Nations

The existing gap between formal governance institutions and local citizens lies at the heart of the challenges faced by most low-income communities such as Makoko. To bridge this gap, the neighborhood management model developed by the team in Makoko seeks to provide a framework to bring together various stakeholders within the community, empowering them to play a leading role in their own governance with support from Lagos State and other non-State institutions.

The key actors within this framework are:

Local citizens (Makoko Community)

Neighbourhood Managers: Newly-formed ‘Makoko/Iwaya Waterfront Development Association’ (charged with oversight of the Makoko community) and individuals (charged with oversight of different subcommunities)

Traditional rulers (baales)

Lagos State Government (and associated agencies and parastatals)

Civil society groups

Private investors

Consultants

Non-governmental agencies

The pivotal role of ‘neighbourhood manager’ is assumed by the newly established Makoko Community Development Association, which undertakes broad oversight on governance within the community. The Association acts an interface between the formal and informal governance structures, and a point of convergence for all major stakeholders within, and without, the community (see the information below). The Association will have a Board of Directors comprising nine community members (sitting for a term of six years) including traditional rulers, leaders of cooperative societies (trade associations), leader of the youth group, leader of the women’s group, and elected members of the community.

The main responsibilities of the Association include:

Cooperating with agencies and institutions responsible for collaborative community service delivery

Mobilizing community members to participate in sustainable development of the community

Constituting active community members into committees for development and management of different spheres of the community

Mobilizing groups (particularly youth and women) for relevant skills acquisition and training

Maintaining channels for community feedback, primarily through neighborhood managers, to monitor community needs and priorities

Collating, retaining and updating database of development activities (physical, social and economic) within the community

Providing a platform for community members, in collaboration with relevant government agencies, to coordinate, monitor and assess community development activities

Mobilizing resources (community and otherwise) towards establishing an Environmental Protection Fund

The Association will provide a strong institutional platform to oversee community development underpinned by the activities of various standing committees (see the information below). The core committees include Lands and Housing, Environment, Security and Safety, and Welfare and Community Services, with provision for the creation of additional committees depending on community needs. Each of the committees shall comprise of no more than 5 community members, including one traditional ruler (baale) and at least one woman.

Delivering Neighbourhood Management in Makoko (Source: Makoko/Iwaya Waterfront Community, 2014)

Ministry of Physical Planning and Urban Development

⇓

Lagos State Urban Renewal Agency

⇓

Makoko Community Development Association

⇓

All other Government Agencies and Institutions

Private Investors

Non Governmental Organizations

Beneficiaries (Makoko Community)

The Makoko Community Development Association within the Community (Source: Makoko/Iwaya Waterfront Community, 2014)

Council of Baales

⇓

Makoko Community Development Association

⇓

Committee on Lands and Housing

Committee on the Environment

Committee on Security and Safety

Committee on Welfare and Community Services

Other Committees

⇓

Residents and Businesses

A key element of the neighborhood management approach adopted in Makoko is about tapping into the power of self-organization to create multi-faceted solutions to address complex issues, leverage challenges as opportunities and turn the lack of infrastructure into a source of income. Emphasis is placed on sustainability and maximizing value chains within waste-to-wealth cycles to address some of the largest challenges on the planet –environmental protection, economic development and social equity. One example of this micro-management and micro-funding approach in action is the Neighborhood Hotspot developed under the Makoko Sustainable Regeneration Plan.

A key element of the neighborhood management approach adopted in Makoko is about tapping into the power of self-organization to create multi-faceted solutions to address complex issues, leverage challenges as opportunities and turn the lack of infrastructure into a source of income. Emphasis is placed on sustainability and maximizing value chains within waste-to-wealth cycles to address some of the largest challenges on the planet – environmental protection, economic development and social equity. One example of this micro-management and micro-funding approach in action is the Neighborhood Hotspot developed under the Makoko-Iwaya Regeneration Plan. The Neighborhood Hotspot is essentially a physical manifestation of the principles of neighborhood management – a coordinated approach to service delivery at local level, which is inclusive of residents in order to maximize benefits for the local community. Taking a holistic view of community governance and development, the Neighborhood Hotspot offers appropriate and community-led integrated service provision, via flexible infrastructure, within a framework that accommodates existing community structures. With waste-management and energy provision constituting key community concerns, the Neighborhood Hotspot is a piece of dynamic renewable energy infrastructure: a biogas plant generating energy from organic waste, with a structure serving as a community center and a nucleus for local services – grassroots healthcare delivery, training and development, community cooking and urban gardening. It is an approach to new ways of providing basic infrastructure and services for all, against the backdrop of a central government that is struggling to do so.

The Swiss Embassy in Abuja agreed to fund one pilot Neighborhood Hotspot and on December 15 2014, an agreement was signed with the Union of Ogu Baales of Makoko. A Memorandum of Understanding covering the ownership, operation, and use of the Neighborhood Hotspot has been signed between the urban design agency, Fabulous Urban, and the Representatives of the Makoko-Iwaya Waterfront Communities in Yaba Mainland Local Government Council, Lagos State (notary certified by SERAC). The Neighborhood Hotspot is simultaneously a business incubator, a place for social exchange and a knowledge center for renewable energy production, waste management, urban gardening and water harvesting—a truly public and social infrastructure that empowers the community. The construction of the structure is simple and based on sustainable, local and indigenous methods of building with wood on stilts. This not only creates the opportunity to showcase climate resilient construction techniques, but the combination of traditional construction methods and local materials engages local artisans in the process, thereby generating jobs and building on local capability. In addition to a biogas plant and kiosk, each Neighborhood Hotspot has the potential to incorporate a range of different activities, providing space for urban gardening, workshop and cooking facilities, doctor’s offices and reading rooms.

Design Matters: Shapping Social Infrastructure

The Neighborhood Hotspot is simultaneously a business incubator, a place for social exchange and a knowledge centre for renewable energy production, waste management, urban gardening and water harvesting—a truly public and social infrastructure that empowers the community. The construction of the structure is simple and based on sustainable, local and indigenous methods of building with wood on stilts. This not only creates the opportunity to showcase climate resilient construction techniques, but the combination of traditional construction methods and local materials engages local artisans in the process, thereby generating jobs and building on local capability. In addition to a biogas plant and kiosk, each Neighborhood Hotspot has the potential to incorporate a range of different activities, providing space for urban gardening, workshop and cooking facilities, doctor’s offices and reading rooms (Fabulous Urban 2014; Fabulous Urban and Heinrich Böll Foundation, 2014; Akinsete et al. , 2014).

As discussed, with all the dialogue and literature regarding smart cities, better cities, and future cities, there is an increasing—and absolutely justified— debate on urban governance, urban management, and policy-making that requires the collaboration of professionals from various disciplines. This last section discusses the importance of design, highlighting the role of designers in solving issues and challenges raised (MoMA, 2011; Lepik, 2011; Lepik, 2013; Hoelzel, 2013).

From the premise of a democratic society, the key to successful urban governance, management, planning and design may lie in the ability to bring together people from different backgrounds with different interests within a complex network (De Landa, 1997; Hoelzel, 2014). Architects and designers are inherently hands-on ‘troubleshooters’, harnessing the propensity to make conflicts spatially productive. Urban design and spatial planning is not ‘moderated’ or ‘managed’ but rather ‘practiced’ and ‘facilitated’ (fuelling discussion on the role of the designer as ‘moderator of social change’). This ‘need to implement’ intrinsically constitutes the major contribution of the profession to improving cities. The smartest and best-intended policies are useless without implementation. The manner in which urban spaces are designed, built and materialized contributes a great deal to the success of urban strategies and governance: good design is the structural embodiment of good urban governance.

As noted, in order to realize projects like the Neighborhood Hotspot in low-income environments such as Makoko, it is absolutely crucial to involve the future users, local citizens, at a very early stage. Furthermore, it is necessary to think collectively about the project outcomes and how these can be achieved. Anything less will likely result in failure, as illustrated in the case of the Ashogbon market in the Ilaje and Bariga communities, opened in June 2009 by Lagos State Government. Ilaje and Bariga were two of the nine officially designated slum areas in Lagos that received funding under the LMDGP before the program was terminated (World Bank, 2014). Intended as a fish market, today it is used as a junkyard for car parts.

It is clear that the location, the design and the requirements of the planned functions were not sufficiently discussed with the local community beforehand. The populace’s needs in pursuance of their fishing-related businesses such as trading and selling were not understood, which should be the core task of designers. Such processes may be lengthy, difficult and troublesome but they are necessary for the success and long-term sustainability of such projects.

The importance of creating jobs and steady incomes to tackle urban poverty and ensure sustainable urban regeneration has previously been highlighted. It is fundamental to developing economic measures based on the socio-spatial conditions of respective communities. Before implementing projects like the Ilaje-Bariga fish market or the Neighborhood Hotspot, it is important to develop operation and management systems. Is the design carried out in a way that people can easily understand and integrate into their operational and business structures? Is the design responding to needs? Are questions of ownership and responsibility clarified? The task and role of designers should be to pro-actively engage and participate in these stakeholder and actor-network processes to achieve good urban design and smart solutions that will make a real difference to society. Therefore, irrespective of how small these projects may be, they will respond to global policy requirements, formulated by the World Bank, United Nations and other such agencies.

It may be a daring thesis, but the lack of ‘good governance’ due to overcharged central or local governments, missing instruments and weak institutions—against the backdrop of rapidly growing city regions like Lagos—may open new spaces for thinking and action for designers. To conclude, the prevailing discourse about ‘good’ and ‘new’ urban governance is ineffective if policy-makers, politicians, sociologists and urban planners do not work closely and collaboratively: ‘horizontally’ across disciplines and ‘vertically’ across hierarchies in governments and organizations. The role of the designer is particularly suited to navigate and mediate between the macro, meso and micro levels since they direct experience through their work, the impacts of the ‘global’ in the ‘mundane’ (Acuto, 2014). As argued, the integration of ‘top-down’ and ‘bottom-up’ approaches is essential to urban and slum regeneration. Carefully designed social infrastructure can be key catalysts for change. They cannot and shall not replace policies but rather complement them. This, however, requires designers interested in working at the intersections of governance, planning and design—who are willing to go beyond conventional roles (Hoelzel, 2015; Van Wezemael, 2014).

The challenges ahead—in the context of rapid urbanization, massive urban growth and urban poverty—are huge. They require change not only at national and global levels, but also at community and household level. There is growing discourse on good governance and smart policy-making, yet international organizations and central and local governments do not work closely enough with local citizens, particularly within low-income groups and informal settlements (Sattertwhaite, 2011), thus leaving such groups without the capacity to adopt these policies. In conclusion, we need governance that is delivered with the people and not to the people.