Walking has great potential. It may not be the fastest or, according to some, the most comfortable way to get around, but it is the only type of movement which doesn’t require a vehicle. By walking more, we limit the influence of our movements on the environment. As a result, creating room for walking frees up space in the city, which can be used to tackle diverse social and environmental challenges. Oddly enough, the pedestrian is often forgotten in the design of our public spaces. This research by design is developed in close collaboration with urban psychologist Sander van der Ham (STIPO). It provides insight into the potential benefits of walking and identifies the necessary design tasks in our built environment to realize those benefits.

The potential of walking

The potential of walking

Walking As a Choice

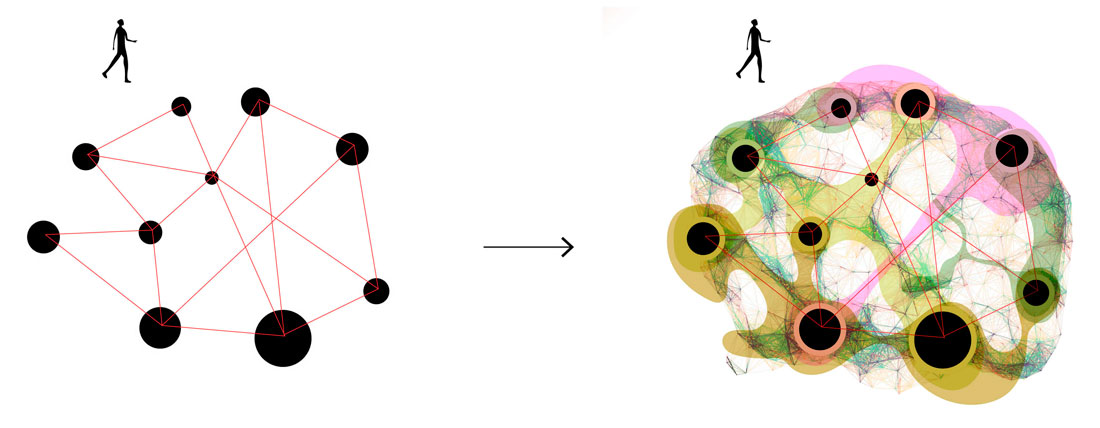

Walking is a choice, although we often don’t make that choice very consciously. In order to create environments that encourage people to walk more, we need to understand how we can influence people’s choice to do so. The choice of walking is influenced by many factors. Everything we experience in the course of our lives is stored in our brain as information. Roughly speaking, we have two methods or “systems” to interpret this information and make choices based on it. System 1 makes unconscious, emotional, fast, automatic and effortless decisions. Choices are based on rules of thumb that originate from previously acquired knowledge, experiences or emotions. They undergo little to no critical reflection. System 2 is rational and requires conscious reflection and costs a lot of energy. It allows informed choices to be made, and it questions the rules of thumb of system 1. To boost walking, we need to address both systems in how we design cities.

The Journey Approach

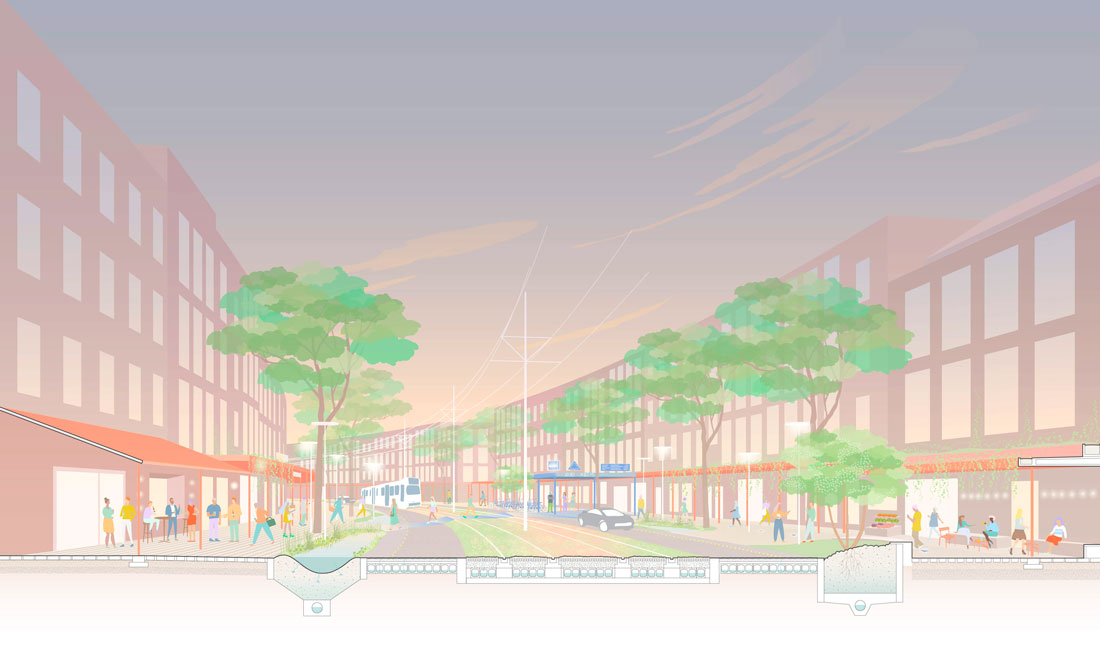

Space for walking is often designed according to the same “mechanical” logic used for roadways. The experience en route is secondary to reaching the destination as quickly as possible. This constantly confirms the prejudices of system 1 in our brain: you’ll get there faster by car or by bicycle. Reconnecting society with walking, after years of applying the generic rules of car environments, starts by applying human-oriented measures to our streets and public spaces. Creating walkable spaces based on an enhancement of comfort, proximity, and reward can bring humanized street designs that subconsciously tempt us to choose to walk.

Rotterdam as a showcase

Walking As a Catalyst for Different Agendas

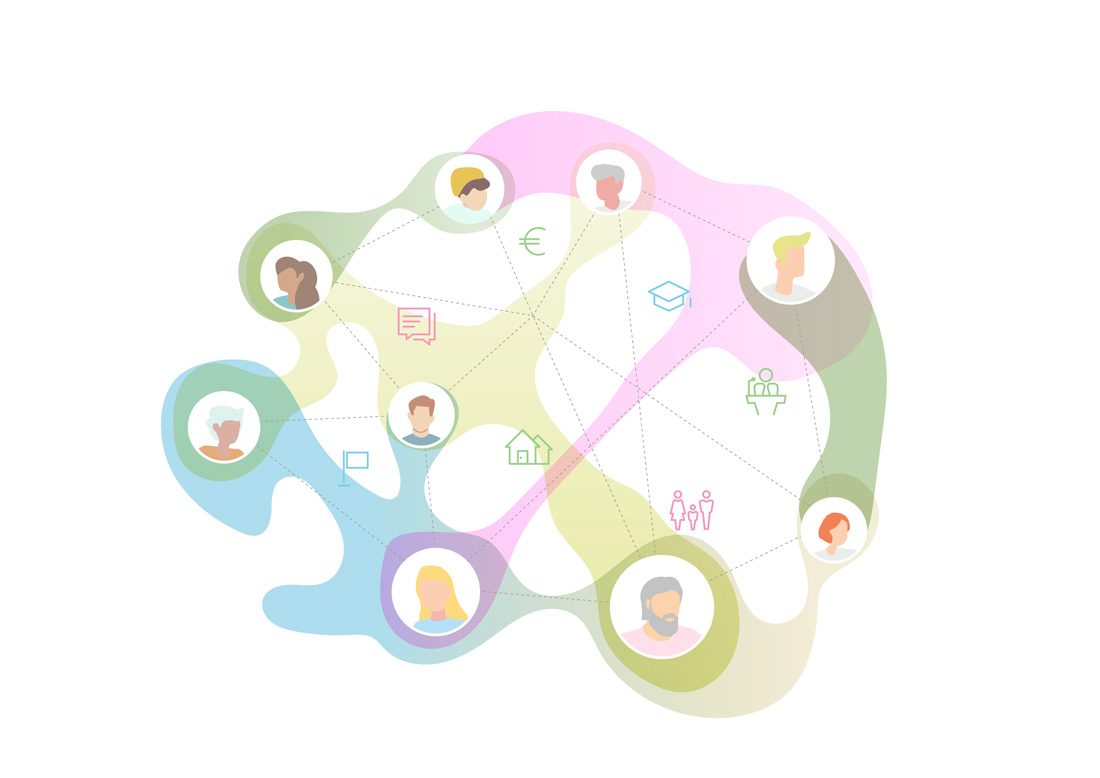

By placing walking in a broader context, we can make better-informed conscious decisions. By critically reflecting on our current rules of thumb and habits, we can make walking a more obvious choice over time. We can achieve this by linking the act of walking to the contribution it makes to social and environmental agendas. This makes the choice to walk more than a mere choice of mobility. It becomes a conscious choice for less air pollution and a cleaner and healthier world. By associating walking with different challenges and objectives, we create arguments that can encourage us to walk and transcend the practical consideration of going somewhere by foot. The more diverse the links, the wider the audience that will feel compelled to walk.

Case 1 Urban renewal districts – Nieuwe Westen

Case 1 Urban renewal districts – Nieuwe Westen, Heudestraat

Case 1 Urban renewal districts – Nieuwe Westen, Vierambachtsstraat

The Walkable City

The 20th century was, without a doubt, the century of the automobile. Mass production of cars revolutionized mobility and represented a milestone in the democratization of transport. The pursuit of speed and individual freedom led to a spatial layout which follows the logic of the car. This legacy is still visible in our urban environment today. Cities are still largely organized to get from A to B as quickly and efficiently as possible.

Case 2 Post-war neighborhoods – Ommoord

Case 2 Post-war neighborhoods – Ommoord

Case 2 Post-war neighborhoods – Ommoord

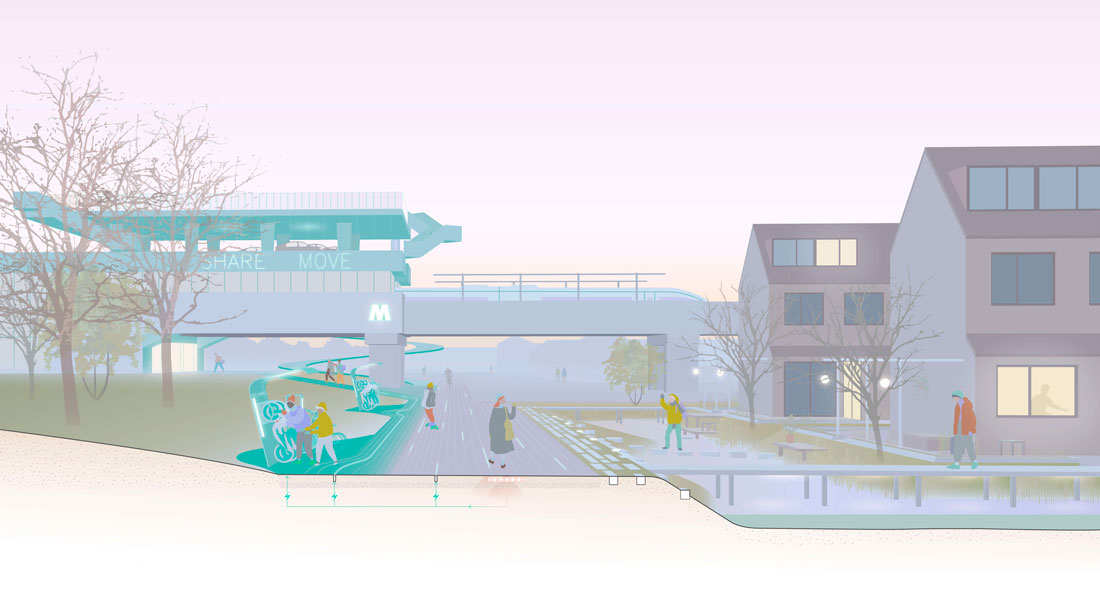

This research proposes a method to transform an infrastructure network into a functional experiential landscape. A walkable city, in which the journey is as important as the destination, recognizes local streets, green-blue networks, neighborhood services and amenities, schools, urban plazas, and public transport stations as the structural elements for an operational journey. The walking realm isn’t limited to sidewalks running parallel to car-centric infrastructure.

Case 3 Residential district – Hoogvliet

Case 3 Residential district – Hoogvliet

Case 3 Residential district – Hoogvliet

In a time of changing mobility, walking can act as a catalyst to support various governmental agendas. Strategies for, for example, climate adaptation, emission reduction, safety, densification and population growth can be associated with the space that is freed up by the increase of walking. However, this link also comes with a requirement in return. The experience of the city must entice residents and visitors to walk. In this city, the human scale is normative, physical activity is stimulated, and space for social interaction is created. A walkable city shares a design brief with that of a sustainable and healthy city.

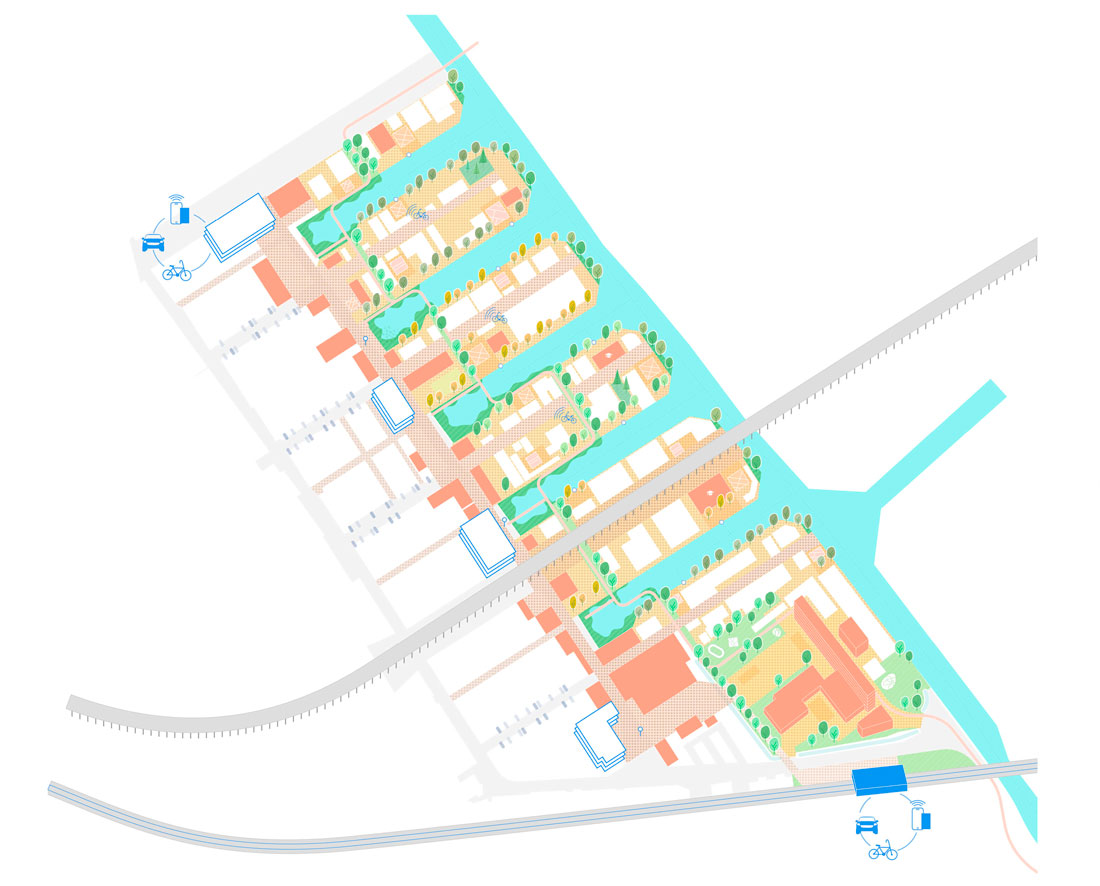

Case 4 Business park – Spaanse polder

Case 4 Business park – Spaanse polder

Rotterdam As a Test Case

To investigate the feasibility of the walkable city, the research takes Rotterdam as a test case. The city is an interesting study area because of the dominant role the car has played in the design of the city. After the bombing of the city center, the Basic Plan for the Reconstruction of Rotterdam was developed. The devastated area was swept clean, creating the opportunity to build a completely new street pattern according to modernist principles. Living and working areas were separated, and space was created for the “traffic of the future”. Four test locations were selected to test the transformation from a car-oriented layout to a walkable city.