“It is said that architects always design the same building. In a sense I have always rewritten the same essay.”[1]

In 1980, just a few months before the opening of the first International Architecture Exhibition of the Venice Biennale, British architectural historian Kenneth Frampton resigned from the curatorial team. His co-curators, Paolo Portoghesi, Robert A. M. Stern, Charles Jencks, Christian Norberg-Schulz, and Vincent Scully, had settled on an approach that emphasized the glorification of the past and positioned postmodernism as an architectural style of historicist eclecticism, in fierce opposition to Frampton’s ideology.[2] Although Frampton was critical of the legacy of the modern movement, he shared Jurgen Habermas’s commitment to “the unfinished project of modernity”[3] and argued for an architecture that would resist the universalizing hegemony of the postmodern times he was witnessing.

Frampton’s “criticism from within,” as Léa-Catherine Szacka has suggested, prepared the field for alternative sensibilities in architecture through which his interest in the ground becomes apparent.[4] In reaction to impending universalization, the historian argued for the specificities of place. In reaction to the postmodern reduction of architecture to images, he reclaimed expressive forms of architectural structure and tectonics. In reaction to the modernist tabula rasa, he emphasized the importance of site and topography. Frampton elaborated his vision in a sequence of texts, articles, books, lectures, and teaching modules,[5] an exploration that had started a decade before his involvement in Venice and would climax in his seminal essay “Towards a Critical Regionalism: Six Points for an Architecture of Resistance,” published in 1983.[6]

In Frampton’s call for the tactile instead of the visual, the tectonic rather than the scenographic, and the hybrid over the homogeneous, one finds evidence that ground and topography were leading notions for the historian. In the first point of both his original text and the extended versions that followed, he argued for an embedded architecture, proposing a radical alternative to absolute placelessness, and in doing so, elevated the specifics of the ground to an essential aspect of the art of building. He argued that a certain form of resistance seemed to develop in a climate where culture became a global concept. As such, Frampton aimed to rescue architecture from the many manipulations of history by providing it with a solid rootedness. But how did Frampton apprehend this rootedness? Was it essential to the architecture he promoted, a mere provocation against the so-called “presence of the past,” or a mechanism in his attempt to reposition architecture ideologically?

Earth Work Versus Roof Work

We may find a first set of answers by taking a closer look at the concept of “critical regionalism” itself. As is well known, Frampton did not invent the term, but borrowed it from Alexander Tzonis and Liane Lefaivre, who coined it in their 1981 article “The Grid and the Pathway,” about the work of the Greek architects Suzana Antonakakis and Dimitris Antonakakis.[7] Frampton’s interest in Greek architecture dates from his first visit to the Acropolis, in 1959, when he discovered the work of Dimitris Pikionis. Then a relatively unknown architect, Pikionis received the commission to design a new pathway, rest stops, and viewing platforms on the Acropolis site in the early 1950s.[8] Pikionis realized his meandering pathway in fragments of marble and Stone pavement in different shapes and sizes, carefully positioning steps, benches, and viewing platforms so each element dissolves in the overall setting. The intervention appears to be an ancient, accidental trail integrated into the conditions of the surrounding landscape. Manufactured by craftsmen who were able to adapt Pikionis’s design to the specifics of the site, the pathway proposed a delicate ambulatory experience. [9] (Hélène Binet captures this quality in a series of photographs produced in the late 1980s.) For Frampton it referred directly to a certain sensibility of the ground: “You can not only see [the ground]; you can read it with your feet.”[10] If Pikionis’s pathway exemplifies Frampton’s fascination with what we might call “earth work,” the oeuvre of another Greek architect represents a valuable counterpart.[11] Aris Konstantinidis, born half a century after Pikionis, proposes a less sensitive but more rational way of intervening on the ground. His weekend house in Anavissos, not far from Athens, is an extraordinary example. Placed on a bare shore in an isolated setting, it anchors itself to the ground with robust, massive columns while enabling the earth to run freely underneath an elegant roof, which marks the architectural perimeter of the rational plan. The stereotomy of the stonework underlines the building’s relation to the landscape.[12] Representing seemingly opposite architectural approaches, Pikionis’s pathway and Konstantinidis’s house defined a dialectical set of interests for the young Frampton. While the pathway proposed a natural melding of landscape and architecture that laid the project within the site, the weekend house suggested a method of forming space that subsumed the site in the rationality of the plan. These two Greek examples demonstrated the tension between an architecture exploiting the irregularities and ambiguities of a landscape on the one hand and a form of structured reasoning of that landscape on the other hand, a tension between “earth work” and “roof work.” It was precisely this tension that inspired Frampton in his quest for an architecture of resistance.[13]

Álvaro Siza’s swimming pool complex in Leça de Palmeira, Portugal, questions the boundaries between landscape and architecture. 1966. © Nicolò Galeazzi

Laid-In Architecture

If “Towards a Critical Regionalism” reads as an attempt to counter universalization with architecture, what specific architecture did Frampton have in mind? He specifically pleads for an architecture that “involves a more directly dialectical relation with nature than the more abstract, formal traditions of modern avant-garde architecture allow.”[14] After several more philosophical explorations, he spatializes his ideas in the last two points of the text, arguing for the importance of the topographic and climatological conditions of a site, the tectonics of architectural construction, and the tactile sensibility of architecture. The ground, as in “topography,” “site,” and “inscription,” is the first item addressed in point 5. For Frampton, the ground can be both a window onto a natural condition and a frame for the historical layers of a specific place. Before addressing Mario Botta and his notion of “building the site,” the historian makes an appeal for bounded architecture, architecture that has little affinity to the freestanding architectural object, but which is inscribed in the topographic, geological, or agricultural history of the site—in other words, a sort of laid-in architecture clearly opposed, as he claims in the text, to a modern approach. “The bulldozing of an irregular topography into a flat site is clearly a technocratic gesture which aspires to a condition of absolute placelessness,” he writes, “whereas the terracing of the same site to receive the stepped form of a building is an engagement in the act of ‘cultivating’ the site.”[15]

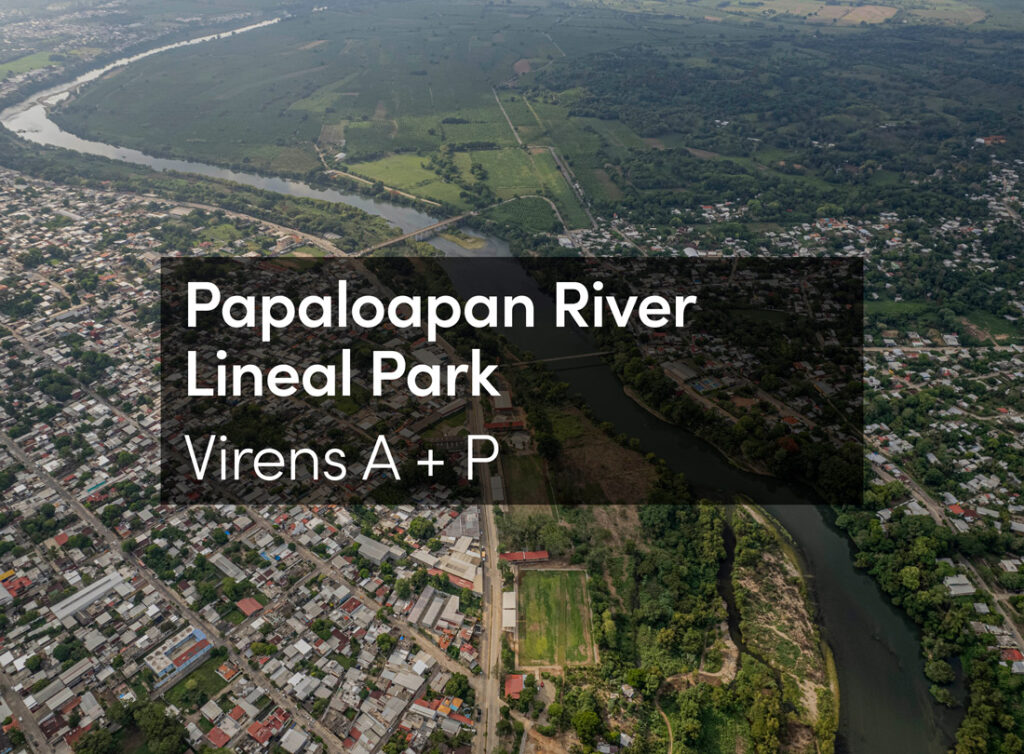

But are all laid-in buildings, according to Frampton, situated on terraced sites and realized in stepped forms? Before and after the publication of “Towards a Critical Regionalism” in The Anti-Aesthetic, Frampton wrote several other versions of his text, which together show the development of his theoretical framework. For example, while the version published in The Anti-Aesthetic omits many examples, “Prospects for a Critical Regionalism,” a text published in Perspecta, also in 1983, cites numerous projects and architects exemplifying his interest in the ground. An example that recurs across these texts is the Portuguese architect Álvaro Siza and his swimming pool complex in Leça de Palmeira.

Set along the northern coastline of Matosinhos, a small town to the north of Porto, the Leça de Palmeira complex is hardly visible from the road. Conceived of as a pathway slowly descending from the coastal road and passing through changing rooms, set parallel to an existing, long seawall, the complex offers a sensory experience even within the building. With no views, the ocean becomes audible. Continuing toward the pools, the pathway dematerializes; Siza’s interventions in the irregular landscape of the rocks are limited to platforms, stairs, walls, and dead ends. While the inclined ramps and walls protect from wind, the materials—reinforced concrete, stone paving, treated Riga wood, and copper roofing—allow the complex to disappear into the landscape. Inspired by the work of Finnish architect Alvar Aalto, Siza was able to ground his building in the configuration of the topography: it is both delicately layered and laid into the site. For Frampton, Siza’s “pieces” are exemplary in proposing an “extraordinary sensitivity towards local materials, craft work, and, above all, to the subtleties of local light.”[16]

Siza’s architecture is just one of many examples cited by the historian. In the Perspecta text, he also references the Scandinavian architecture of Jørn Utzon and Aalto before introducing the work of J. A. Coderch in Spain, Dolf Schnebli and Botta in Switzerland, and Gino Valle, Carlo Scarpa, and Luigi Snozzi (with Botta) in Italy. For Frampton, their architectural approaches testify in each specific case to the regional and local conditions of the site and use specificity at the core of their designs, as he would write in more general terms in “Towards a Critical Regionalism”: “This inscription, which arises out of ‘in-laying’ the building into the site, has many levels of significance, for it has a capacity to embody, in built form, the prehistory of the place, its archeological past and its subsequent cultivation and transformation across time. Through this layering into the site the idiosyncrasies of place find their expression without falling into sentimentality.”[17]

While inclined ramps and walls protect from wind, the materials – reinforced concrete, stone paving, treated Riga wood, and copper roofing – allow the complex to disappear into the landscape. Álvaro Siza. Swimming pool complex, Leça de Palmeira, 1966. © Nicolò Galeazzi

Peripheral Grounds

But Frampton’s search for a grounded architecture also needs to be understood in a different light. Within the context of the powerful winds of a decontextualized postmodernity, Frampton aimed to give attention to architects who had been relegated to the periphery of a system centered around star figures working in specific areas in Europe. For the historian, then, the periphery was also geographic: the topographical conditions of peripheral European regions (Greece, Spain, and Portugal, but also the Swiss Ticino region) enabled him to explore practices with alternative stances toward postmodernism. His interest went beyond the borders of the old continent. As a technical editor for Architectural Design (between 1962 and 1965), he ambitioned an “encyclopedic” editorial policy that resulted in thirty-one issues of AD focusing on the development of modern architecture in peripheral situations, including extensive features on non-European territories like Chile, Brazil, and Mexico. Although the magazine still covered the United States comprehensively, its predominant geographical focus shifted under Frampton’s direction to continental Europe and Latin America, which were featured in extended articles on specific regions, architects, and single buildings.

Frampton’s attention to these peripheral conditions allowed him to explore local environments, vernacular elements, and material cultures. In “Prospects for a Critical Regionalism” and in subsequent reworked versions of his Modern Architecture: A Critical History, the British historian cites projects by the Argentinean architect Amancio Williams, the Brazilian architect Clorindo Testa, and the Venezuelan architect Carlos Raúl Villanueva, as well as the “sensual and earthbound architecture” of Mexico’s Luis Barragán, whose unification of architecture, landscape, and gardening is the basis of the topographic dimension of critical regionalism: for Frampton, while Barragán remained committed to “large, almost inscrutable abstract planes set in the landscape,” his houses “are nothing if not topographic.”[18] Frampton continued advancing his interest in peripheral conditions in several edited publications and essays.[19] The list of his writings is long, his conviction strong: “It is my contention that Critical Regionalism continues to flourish sporadically within the cultural fissures that articulate in unexpected ways the continents of Europe and America. These borderline manifestations may be characterized, after Abraham Moles, as the ‘interstices of freedom.’”[20]

Just as his Modern Architecture argued that architectural modernism was as much a struggle for social and political expression as an aesthetic statement, in these works, Frampton constantly looks beneath the aesthetic surface of buildings in search of deeper meanings. His interest in the ground—its tactility and sensuality— enabled a significant number of practices to come out of the shadows both in Europe and in Latin America. We might even wonder if critical regionalism was not also about architectural sensibilities that have traveled through cultures, from one territory to the next,[21] from one ground to another.

Álvaro Siza. Swimming pool complex, Leça de Palmeira, 1966. © Nicolò Galeazzi

Uncovering the Earth

Topographic architecture might generally be comprehended in different ways: as a compositional understanding of the ground figure of the project, as an interest in the cultural and material histories of a specific site, or as an awareness of the technical constraints and opportunities that a site can imply. For Frampton, however, there is still another aspect crucial to the term: topographic architecture needs to be situated within an ideological perspective. Frampton was clearly not interested in sentimental architecture. His Marxist reaction to universal capitalization, and his refusal of Western architecture’s hegemonic turn toward history,[22] let him develop a theoretical apparatus that would enable an architecture of resistance. As such, critical regionalism proposed a set of disciplinary categories that aimed at understanding architecture beyond (aesthetic) universalization, as a set of political values.

But if Frampton had originally set out these categories to enact a political agenda, the text’s critical fortune has blurred this objective. Critical regionalism became all too soon a historical document, understood as a poetic, a-critical, and apolitical interest in peripheral conditions. In an epoch when architecture needs a renewed frame of values, Frampton’s engaged theory of the discipline is more than ever food for thought.