Every single subject in the social – and consequently political – context of our country is challenged by the very fact of being tiny, as a being, as a person, as an ego, as a society in vast surroundings.

We are 300,000 Individuals

However, our web of infrastructures never seems to reflect this fact. True, we are probably more inclined to have a risk-seeking, problem-solving attitude, but even when viewed through the most rose-tinted glasses, an element of absurdity can be detected when it comes to the Icelandic context. And the sad thing is that this element causes a ridiculous amount of resources to be consumed; desiring it, giving it all it takes, then losing it, because we shun critical and abstract thinking, and we refuse to take our egos out of the equation.

The vibrant issue of the moment, the building of a new National University Hospital, is a perfect example of a problem that is screaming out for a solution, underpinning the centrality of the role of the academic and the professional in a societal context. The people that society traditionally calls upon to gather specialized abstract know-how, are trained within strategic fields of responsibility (partially at society’s expense) in order to be accountable, for the greater good of society.

Taking Responsibility for a Standpoint

In the 1960s, the London-based architectural and planning practice Llewelyn-Davies, Weeks, Forestier-Walker and Bor was commissioned to work on a new hospital in Reykjavík; not a holistic solution to meet all the needs, but rather to establish a health science center. The old hospital was outdated, and its preclinical research units scattered around town in different kinds of industrial and commercial housing.

Many were skeptical about establishing a university hospital in the Icelandic context. They felt that people should be educated in more dynamic melting pots abroad – and the local health system should mainly serve, not educate or undertake fundamental research. Some professors at the very same institution were even quoted as saying that the University of Iceland was a second-rate university, which it should be closed down and the students sent overseas.

Some of them, curiously enough, became central to the planning of the hospital, working alongside economic governmental representatives and the Llewelyn-Davies, Weeks, Forestier-Walker and Bor team. When questioned about the schizophrenic aspect of their situation, they admitted it – but seemed resigned to laying their skepticism to rest so as not to jeopardize their academic status.

This example bluntly states my first point of concern – the priority repeatedly given to individual interest, along with an inability and lack of will to maintain the abstract, specialized point of view; to see the wider picture, and translate it from there to other subsystems of society – a fragile and small society that cannot really afford to make mistakes on such a scale as this.

If academic freedom and peer review is worth anything, it is worth exactly that; to show a sufficient degree of respect and aspiration for society to state the obvious, to mirror, criticize, take responsibility for its evolution.

In turn, by doing so, society might eventually learn to understand and, from there, even welcome the specialized vision, understanding that it would be strange and unnatural to demand the world to look the same from the standpoint of a doctor as it does from that of an architect.

The Will to Power – the Power of Will?

After decades of planning, with dedicated support from the government, the firm’s design was finalized in 1978: it was to be 16 buildings with linking corridors, located on the same site as is currently being considered. The construction could at long last begin. But, to cut the story short, after much ado, only a single one of the 16 units was actually built. And in fact that took ten years. The full will of the authorities, and very little opposition, produced one out of sixteen buildings, in a time span that outdated the original plan.

Redoing (and thus repaying for) things in Decision Phobia

The next extremely important point comes in the aftermath. In my lifetime, I have witnessed a threefold design of that very hospital. After hearing about the firms design from relatives, I later worked at an office that collaborated with a foreign design firm, and won an international competition for the commission to plan the hospital premises. As an employee, I followed that process from the sidelines. Only a few years later all this was thrown out, and for the third time I am witnessing this cycle repeating itself. Who pays? Obviously the architects that take part, since the planning is repeatedly subject to competitions where many offices end up working on their proposals without getting paid – but sadly, enormous sums are also taken from public funds – funds that could be distributed other ways, buying equipment, financing research or supporting the health sector.

Good planning is crucial – don’t be mistaken – but: How often can a minuscule society pay for the clothes of the same emperor? And why are there so few children out there stating the obvious?

An even sadder fact is that architects seldom praise, with any certitude, the spatial placement of the relatively massive hospital complex within the fragile tissue of the metro village – with the exception of the very team that sits on the commission at a given time.

Why do architects not find themselves forced to point out that a national motorway running through the most fragile part of the urban tissue is not necessarily a good idea? That an intervention of this size will maintain the obvious urban rupture already created by the current hospital and the main road? Why, from an urban point of view would this be interesting or good?

Whose Utopia – for Whom do these Bells Toll?

The current planning committee of the new hospital describes a wonderful dream. One can’t help but believe, due to the convincing power of the semiotics used in the press material – or maybe out of mere denial – that there is an underlying understanding and agreement on how to prioritize and plan.

But then again – who exactly are the people responsible for this consensus? What are their premises? Obviously, we all dream of top quality services – but what is the basis for the decision-making? Is it a utopian vision or simply our attitude towards life; that we equate human rights with getting nothing but the best? At what cost – and do we even have the money to begin with?

The Burdening Fact of Democracy

And so, the central problem has to do with the abstract and complex woven fabric of infra- structures that have to be taken into consideration – in many different professional languages, calculated, reinterpreted, and translated. We need to come to a consensus – which is not the same as forcefully demanding us to blindly agree, crossing our fingers and praying for the best. One could wish for a development in our democracy that would form an agonistic field, in order to get the big picture out there, in every conceivable and relevant language, to negotiate, understand the benefits of sharing doubts and opinions in order to strengthen the base of the decision- making, trying to analyze and understand over how many levels, both democratic, urban, global even, this problem stretches. Interestingly enough, the discourse does not seem to succeed in transcending extremely limited realms of professional and political discourse. It seems to be caged in parallel discussions, lacking the ability to reach an appropriate collective discussion field of the various stakeholders, incorporating the maximum number of relevant arguments at any given time.

Apparently, the idea of this transcendence of the discourse threatens its “stability”. One would think that a balance of such fragility – and a situation denying itself an objective trial before its concrete execution – should immediately raise doubts. Is there balance, if its stability is threatened by the obvious being pointed out?

We are too few, wearing too many hats. It is, of course, absurd to expect that a majority of people in this society has a carefully constructed opinion on socio-philosophical matters. Representative democracies were surely developed in order for people to send their representatives into the political field, to take action according to the respective interests. But here in Iceland, as seems to be a somewhat central problem within western society, the individuals appear somewhat lost in the woods of hazy and tangled visions and unclear promises – as well as premises. It lies increasingly in the hands of each subject to more or less individually carry out their political participation, as the political party dialogue becomes estranged from social interests. The problem – as well as the gift – is that we have different abilities. To believe that we can, each of us, individually operate on so many different levels of complexity in our everyday life would be to maintain the Übermensch nonsense that dominated pre-crash discourse in Iceland. It is simply impossible for an individual to keep track of the complex bundle of questions on a societal level, building opinions on a multiplicity of issues, based on critical arguments and thought. Ultimately, however, this does not mean that we have the luxury of not caring. This is essentially why we chose democracy. But our channel of discourse, stamina and investment into the continuous collective dialogue, refinement and progression of critical debate seems to be challenged by powerful sedative agents. We seem to be simply too busy; with work, with life, with trying to stay “happy”. Ignorance is also power. Could this be the reason why so many of us seem to wish for a strict, but kind, fatherly figure to come and save us once and for all; our whisper for a benevolent dictatorship?

The Four-Dimensional Reality of a New Paradigm

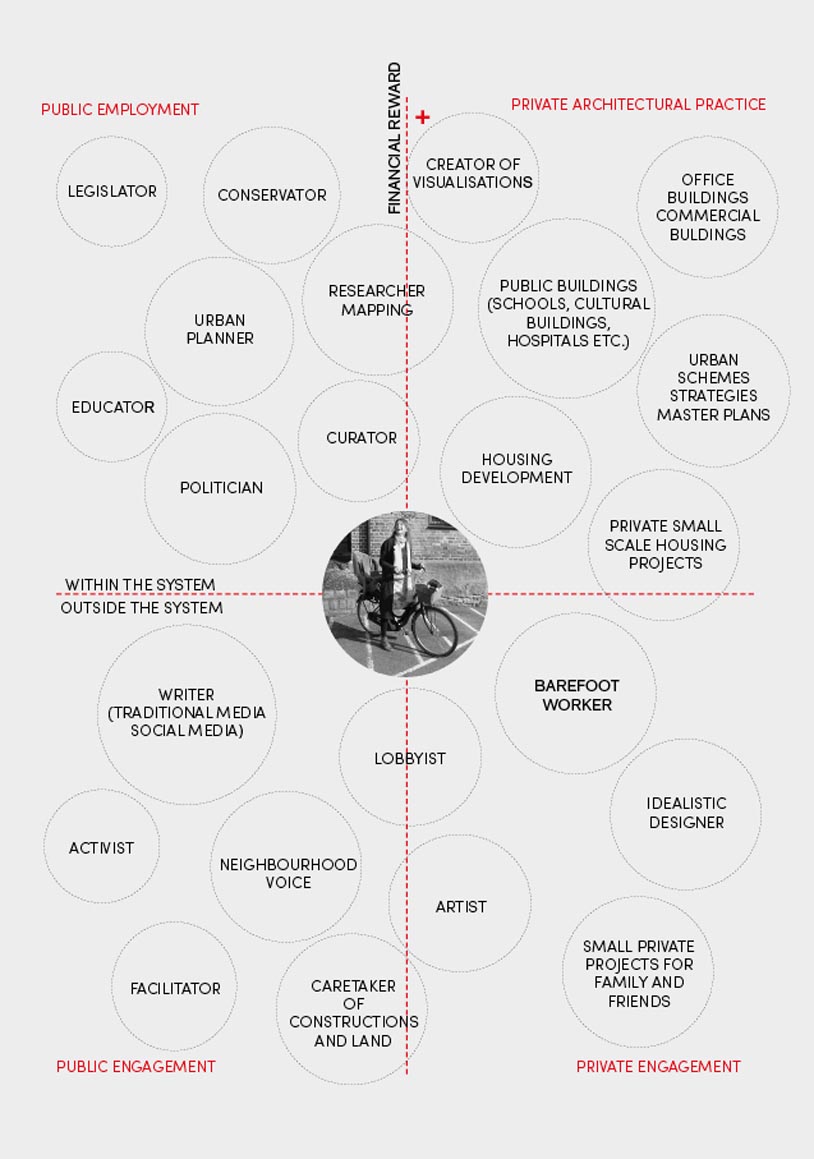

Back to the sociopolitical role of the architect. Although this by no means makes architects the sole experts in the decision-making field, I sincerely believe that design thinking has an important role to play with our post-grand-narrative society. Designers and architects are a rare breed when it comes to the training of thinking four-dimensionally in space and time. The fact is that we are trained to operate on multiple levels simultaneously, think through and plan abstractly, to prepare for ignition, construction, be ready for change of direction along the way, and be able to produce an instant translation of that change into multiple professional languages. Ours is not the luxury of being able to express ourselves within one realm of knowledge. On the contrary, we are trained to receive information, put that information into a complex web of context – social, material, economical, aesthetical, ontological and always, always, by nature, political.

It is the misfortune of the profession to fail to embrace this responsibility. Because we are always too busy. Because we fail to invest in critical discourse within our field, fail to carry out the real messages about our findings to the outer world, fail to refine, reflect and re-appropriate our status of knowledge according to the findings of other realms. I want to propose two things:

On one hand, that we put all our effort into searching for our equivalent of Hippocrates’ oath, whether we are architects, engineers, flight attendants, as citizens – that we ignite our vocation as specialists, partakers in society before we are vendors of service or products.

On the other hand, wouldn’t it be hope-provoking if we could make the most of this melt- down situation and define the agonistic field that could start in an abstract, yet tangible and loving manner, to solve the central problems of this wonderfully resource-rich, but scarcely populated, island, to come up with a genuine suggestion on how to be a miniature democracy in the absurdity of vastness.

One could say that the vitality of the field of architecture in a given nation is a good indicator of the overall strength of its economy. The mass unemployment of Icelandic architects after the economic meltdown lends validity to that assumption.

However, to say that architects are useless for society in a time of crisis would be nonsense, and the case of Iceland again supports that view. Below is an attempt to map the fields in which architectural expertise could be useful.