Collecting finds its origins in the expeditions of early plant hunting, a practice that procured live or dried specimens for further study in confined environments. As a basis for botanical study, collecting is centuries old and was once renowned for its exoticism and adventure.

Sedum compactum

Outside of its historicism, the practice of assembling a collection of specimens is also a practice in experimentation, of lessons learned and plants tested that can offer designers a chance to build knowledge of a different sort, a kind of learning that attempts to align itself with the qualities of transformation we are so fond of explicating, but have little evidence of testing through design. Tiny Taxonomy at the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum became an opportunity to test plants that were raised by discrete and specialized nurseries in order to offer a setting in which these exceptional and singular specimens could be made accessible to visitors accustomed to the examining artworks.

Daphne arbuscala “Muran’s Castle” // Shrubby daphne

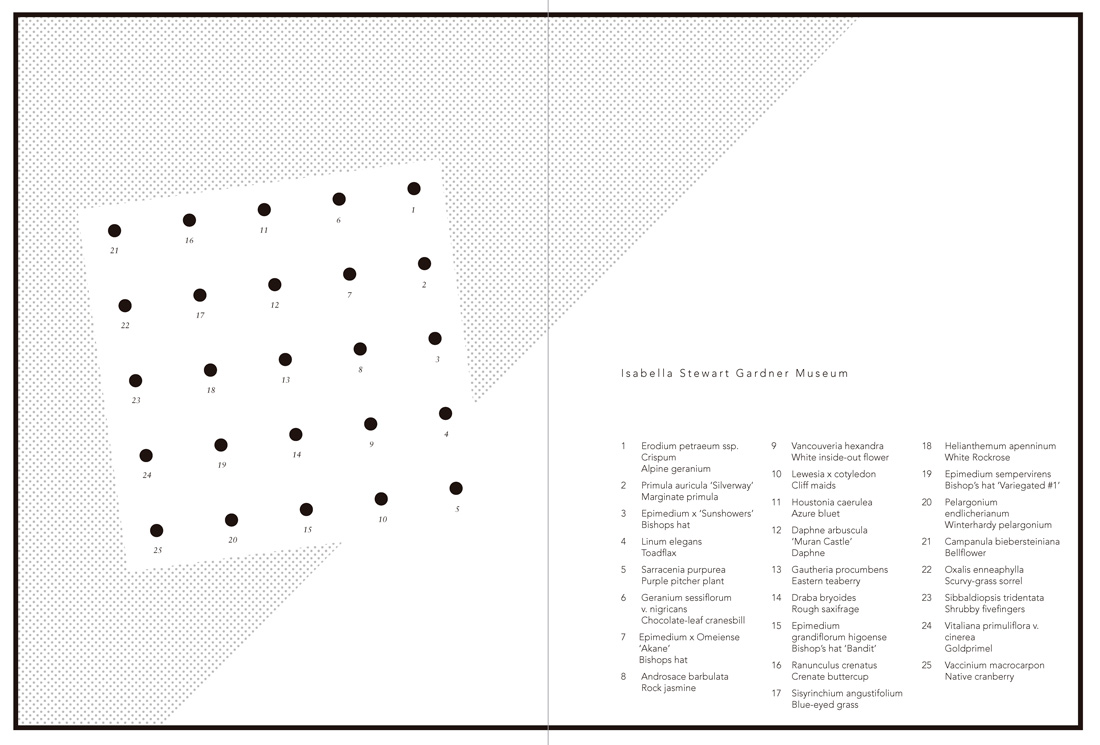

The Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum is a collection in itself. As a patron of the arts and an avid traveler, Isabella Gardner was a visionary in her time. The museum’s collection is an atmosphere; it envelops the visitor with its stories, histories, and memories, imparting a magical knowledge through experience with every object, painting, and artifact. The museum, which was once her home, is built around an inner courtyard that offered plant life for equal consideration among the works of art. Within the interior of the museum, collecting is embedded as a practice while outdoor courts remain heavily exposed and rarely visited. Since the ambition of the project was to further the translation of first-hand experience to the visitor, a cosmopolitan collection process was instigated, wherein the gathering of specimens was made synthetic—from the pursuit of rare plants breeders to lichen scraping—suggesting a highly constructed form of specialization. Rare plants were collected for exhibition, refocusing the attention of the visitor and elevating the status of each individual.

The challenge of exhibiting ‘landscape’ as a profession, a scale or a genuine place is made especially clear in the context of a museum, as it promotes the objectification of the field, by displaying the artifacts of its construction. Within this more established model, it is the drawings, diagrams and prints that help elucidate and represent an imagined place, conjuring nostalgic illusions of a landscape. The site of experience is independent of the museum, as the visitor is drifts into the consideration of the its representation alone: “… while limited in time, location, and materials, exhibitions raise issues of intention, content, audience, and the means by which the organizers enact their program. Given the sizeable dimensions of landscape architecture, its display is a task far from easy– a task made doubly challenging by the use of representations and surrogates to stand in for genuine places. Exhibitions, however, can be an effective means by which to inform, persuade and even delight a museum-going public.”

Draba bryoides // Rough saxifrage

This inclination away from the artifact runs counter to the trend of garden installations, and reveals the prospect of returning to a scale of landscape making that both deals effectively with the living plant and its environment. A collection is always brought into limited circumstances to stimulate further consideration. Small plots of ground form extracted habitats that demonstrate the remarkable form of a plant, and more importantly its progress. Repeat outings reward the museum-going public with the wonder of an inflorescence emerging from what had appeared weeks before as a simple stalk, as most of these plants share the adaptive trait of brightly colored, oversized flowers to attract pollinators. What may once have looked mundane or common would be transformed, cultivating an intimate acquaintance between subject and object.

Vancouveria Hexandra

Due to the range of habits represented by these tiny plants, each cylinder could barely describe a portion of its habitat, nevertheless the living plants settled into each miniature landscape, elucidating their individual adaptations. Plant structure is foregrounded over physical forces, so that a tendency for stems to proliferate could be observed by an abundance of such specimens, while plants that emerged opportunistically from crevices were carefully planted to explore their progress from beneath an unyielding rock. Some plants, such as Daphne arbuscula, are rare in cultivation and are thought to be extinct in the wild. Therefore, the opportunity to present this miniature plant at eye level is equally an opportunity to observe its dense clusters and smell its fragrant pink flowers, not as a surrogate, but as a means to communicate. At the same time, seemingly common plants like Vaccinium macrocarpon (American Cranberry) materialize as singular specimens, as this species of cranberry is the ancestor of the plants now hybridized for cultivation and planted in the bogs of Cape Cod and New Jersey. The distinction between common or rare becomes secondary to the remarkable adaption of growing small.