Beyond a certain scale, architecture acquires the properties of Bigness. The best reason to broach Bigness is the one given by climbers of Mount Everest: ‘because it is there.’ Bigness is ultimate architecture. Rem Koolhaas

[T]he destiny of humanity [architecture] depends upon the attainment of its highest type. Friedrich Nietzsche

Approximately 40 years ago, a set of wild images and poignant narratives borrowed from and simultaneously projected back onto the undeniably congested reality of Manhattan were condensed into a retroactive manifesto for contemporary architecture by the young architect Rem Koolhaas. With its “unconscious” theory of Manhattanism and its antiurban concepts of programmatic instability, auto-monumentality, vertical schism, the irresistible synthetic, and the technology of the fantastic, Delirious New York insolently challenged all remaining forms of public life and brought into question the alleged self-evidence of an urbanism of good intentions.

Koolhaas documented his revolutionary model with “a mountain range of evidence without manifesto”—a series of developmental forms of early 20th-century Manhattan, distributed across the island as an amoral pile of defiant architectural debris. Processed and presented retroactively, Koolhaas’s matter-of-fact yet custom-made theory became the definitive expression of the so-called culture of congestion: an archipelago of skyscraper islands made of extreme solitudes, plotted on a matrix that radically segregated one from the other, and floating imperceptibly on the vast sea of capitalism.

What may be regarded as the definitive expression of this model, Rockefeller Center, perfectly embodied the formulations of Manhattanism by paradoxically taking them beyond their limits of performance and scope of imagination. Through the relentless amalgamation and integration of technologies and motifs, this unique, complex artifact both incarnated and defeated the conditions that nurtured it, introducing a radical challenge to the ubiquitous grid that hosted it and gently anticipating a second leap, still to come, that would not only exceed the domesticated logic of the urban through the antiurban but engulf the territory itself, promising a new threshold for architecture.

Since then, two major phenomena have fundamentally transformed the volatile scene of contemporary architecture culture: the assimilation of complexity theory and the advent of digital culture. Both have been incorporated and vastly naturalized by the discipline, empowering its capabilities as a medium of integration of diverse domains of practice, irreducible forms of expertise, and disparate organizational scales. Concurrently, the wild rationales of extra-extra-large developments have begun to technically converge and fulfill this promised territorial threshold in the real. The Generic Sublime takes, by means of these radical disciplinary transformations, the open possibilities of Manhattanism beyond Manhattan, by synthesizing—this time in real time and without cynicism—the process of becoming territory of architecture, at the age of global developmental culture.

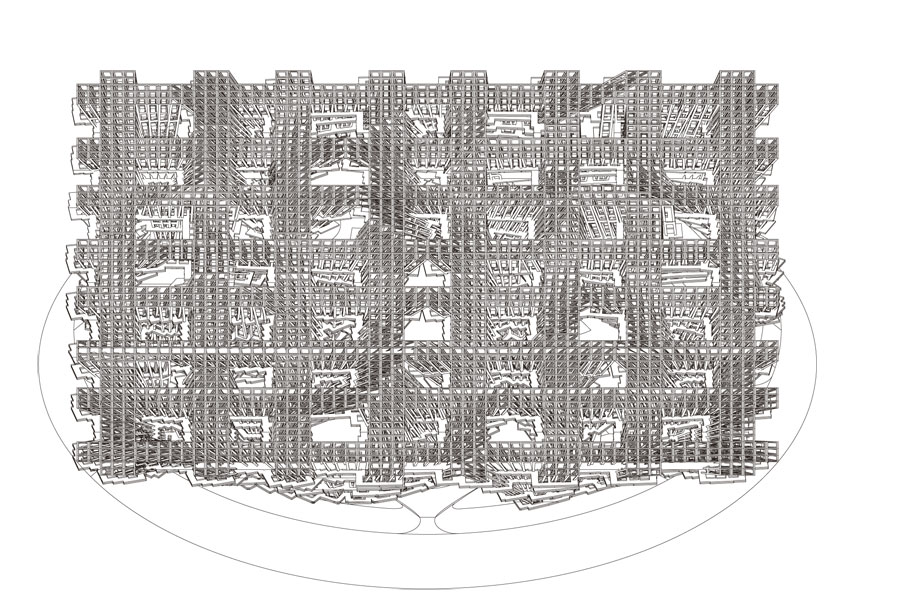

Skyscraper collectives, tower agglomerations, high-rise housing, mixed-use developments, luxury condominiums, airport hubs, suburban office enclaves, industrial and technology parks, hotel complexes and resorts, conference and financial centers, entertainment venues, gated communities, theme parks, branded cities, new central districts, and satellite cities: what is the latent potential of extra-extra-large typologies if freed from the typological traditions of urbanism and the segregation of disciplinary domains? What is the reach of this potential in rethinking the contemporary urban condition and reimagining future architectural models?

The Generic Sublime explores the sublime condition that generic organizations attain when operating in multiples. It investigates how the modernist concept of the generic— once assumed to achieve universality by means of organizational homogeneity, formal neutrality, programmatic blankness, lack of identity, and insipidness of character—holds the potential to turn into its very opposite: the singular, the irreducible, and the extraordinary. This book investigates the principles embedded in extra-extra-large developments to construct models of the ubiquitous and self-contradictory phenomenon by which urbanization constructs the territory in which it is grounded.

The Generic Sublime embraces the project of its predecessor, the American skyscraper, to radically integrate the urban in a single, antiurban, cybernetic universe: a large-scale architectural machine that breeds unpredictable organizations through organizational complexity, systemic inclusiveness, paradoxical coexistence, and reciprocal intensification. But it initiates a second, simpler and vaster, megalomaniacal leap: the envelopment, in an all-embracing, multiplicitous architectural interiority, of pure territorial exteriority, where infrastructures, ecologies, and urban conditions interact in the synthetic spatial field of a single building.

Like the skyscraper, the Generic Sublime constitutes a tightly contained system of systems, where the discrepancy between the convoluted complexity of the interior and the compact uniqueness of the envelope engenders the unprecedented power of liberating the artificiality of the antiurban. However, the potentials of its anthropomorphic ancestor of the past century are here upgraded by the self-superseding form that the antiurban takes when assembled in a collective: the configuration of instantaneous archetypes made of a multiplicity of “cities within the city,” now cohesively unified into the ultimate form of primeval architecture.

If the American skyscraper brought into architecture culture the opportunity of a realtime, open-air laboratory in which to explore a whole new set of forms of collective life that, as Koolhaas writes, “explode the texture of normal life to offer an aggressive alternative reality that discredits all naturalistic urban realities” and incarnate the metropolitan unconscious in a medium for the “thoughtless constitution of theories,” then the Generic Sublime aims to consciously develop model-manifestos of the global architectural unconscious, crafting contemporary forms of the sublime out of the multiplication, assemblage, and magnification of the generic. Ultimate expressions of a future anterior, these upcoming archaic configurations escalate ordinary versions of the present to extraordinary versions of the future, here among us. Implausibly banal, astonishingly vulgar, and, more often than not, plain tacky, these versions both embody and betray their initial premises—based on the ruthless logic of maximum commercial benefit in global development—by radically following and alienating them as a result of sheer organizational excess and endless territorial extensiveness. The Generic Sublime appeals to the highest level of non-linear emergence in architecture and engenders a prosaic form of the grandiose.

Radically domesticated, the territory breeds the artificial wildness of the boldest architectural artifacts, shifting the intellectually comfortable condition of estrangement through shock into that of self-alienation through differentiation, where architecture takes on the blunt force of an artistic invention through a self-propelling condition, which can be concurrently regarded as neo-natural, over-urban, or utopioid. Restricted, austere, simple in its premises, plentiful, expansive, extreme in its expressions, and fundamentally unbound by any dependence on reason, the Generic Sublime employs rationality as the ultimate means for the propagation of its canon: brutal indifference.