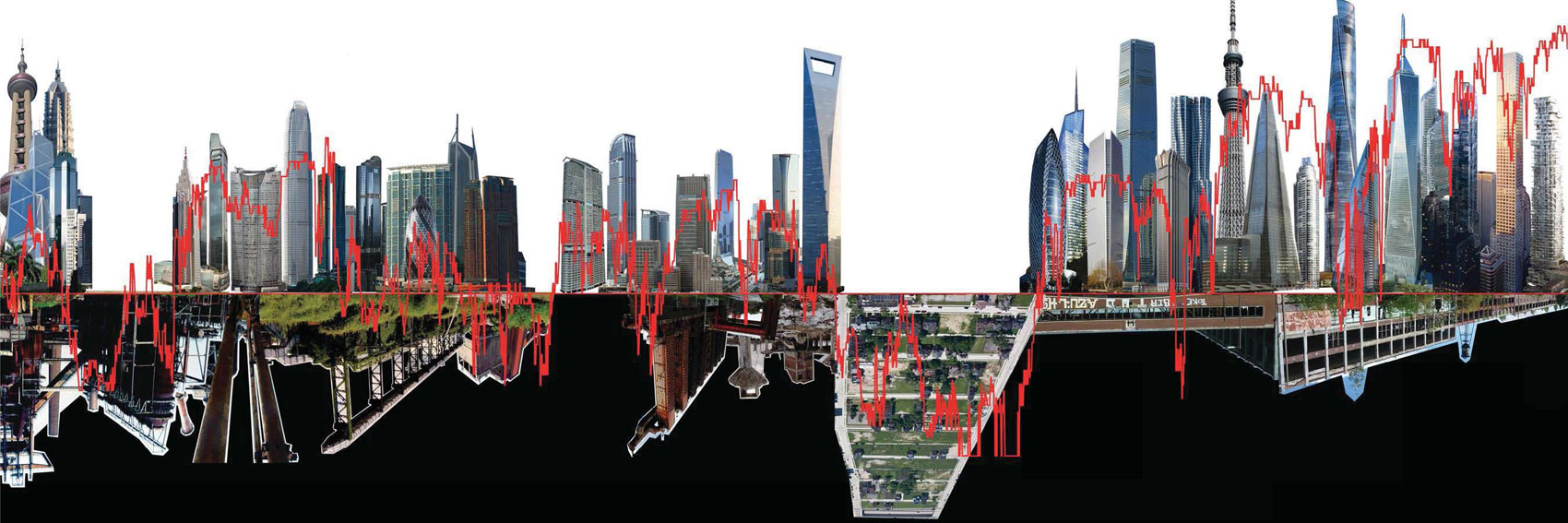

In the contemporary metropolis, the physical infrastructure of urbanism is mirrored closely by the fiscal infrastructure that constructed it. This fiscal foundation is hardly invisible; in global cities like New York and London as well as emerging ones like Shanghai and Istanbul, an ever-growing skyline of luxury towers reflects all too closely the speculative peaks and valleys of the financial markets that funded them.

Just as buildings like the recently completed Shard (one hundred ten stories on the South Bank, both the tallest structure in Europe and the highest real estate prices in the United Kingdom) reflect London’s overabundance of capital, speculation, and design talent, the slums of cities like Cairo and the vacant factories and inner-city neighborhoods of deindustrializing cities like Detroit reflect the absence of the same things. One could not exist without the other; as academic critics of capital like Neil Smith and David Harvey and populist critics like Michael Moore have argued for decades, the financial returns and tall towers of the global city are not only the opposites but, in some ways, the direct cause of the poverty seen elsewhere. General Motors, as Moore has persistently argued, created Flint, Michigan, by growing there, and destroyed it by leaving.

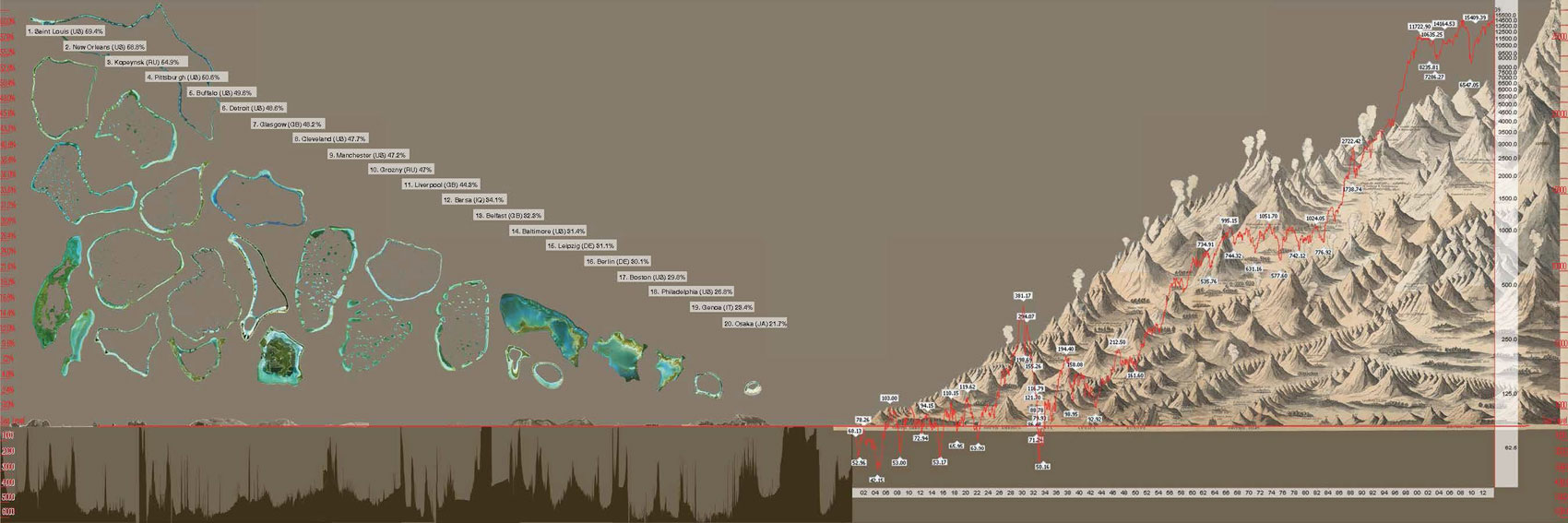

America’s shrinking cities [1] comprise some of the deepest trenches in this fiscal topography of financial disinvestment. In places where deindustrialization has been draining a city for decades, like St. Louis and Camden, along with Detroit, house values are often so low that even those constructed directly before the recent real estate crisis are worth close to nothing. Where the global city’s physical and fiscal landscapes resemble mountain ranges—Himalayas of finance, capital, and profit—those of shrinking cities resemble archipelagos of modest atolls, most only a few feet above water. In the shrinking city, only downtown and a few prosperous neighborhoods are close to the surface, above which modest profits are possible. These atolls of profit may be thought of as the peaks of a submerged mountain range. Not far offshore lie the products of the most recent market boom, renovated lofts and condominiums constructed by private developers. In these places substantial public-sector subsidies permitted the breaching of the profit surface, allowing islands to form for a few short years.

The rest of the shrinking city comprises the submarine trenches and abyssal plains of an ocean of loss. In neighborhoods inhabited by thousands of low-income city residents exist longstanding conditions of deindustrialization, abandonment, and poverty. Here the city’s housing fabric may be nearly completely destroyed, as in Detroit, or well on its way, as in Flint, Michigan, or Buffalo, New York, where hundreds of houses have been demolished each year since the onset of the fiscal crisis in 2007. In these fiscal trenches, houses worth little or nothing deteriorate openly and rapidly, further diminishing the value of those around them. New housing is possible only with great subsidies, constructed by non-governmental organizations seeking to house those most in need. This “underwater” physical and fiscal landscape is modest and unassuming. Its aim is not to transform the landscape of abandonment but to ameliorate its most brutal characteristics: homelessness, drug addiction, and slum living.

Detroit’s Typological Topography

America’s largest shrinking city, Detroit, is by now a well-known icon of decline. Since the 2008 financial crisis the city has become a convenient emblem for seemingly every problem faced by America: racism, deindustrialization, globalization, foreclosure. Images of Detroit’s spectacular abandoned buildings have become almost too common, though their continuing publication indicates that they have not yet lost their shock value. While this objectification of America’s poster city for crisis is accurate to a certain extent, it also permits a guilt-free displacement of issues that are surprisingly common to every American city. Detroit’s summer 2013 declaration of bankruptcy confirmed the city’s sad status as America’s national crisis capital, notwithstanding declarations of its imminent revival from boosters such as Richard Florida.

The objectification of Detroit as a symbol of ruin also ignores the very real development renaissance the city experienced between 1990 and 2006. Far from being a symbol of decline, Detroit during those years was a surprisingly optimistic place wherein the fiscal topography of the shrinking city experienced dramatic transformations through equally dramatic urbanistic interventions. Exploring these interventions is a useful exercise, not only for broadening our generally simplistic view of the shrinking city but for better understanding the complex relationship between architecture, urbanism, and real estate development, and their potential to shift fiscal topographies where global cities merely reify the status quo.

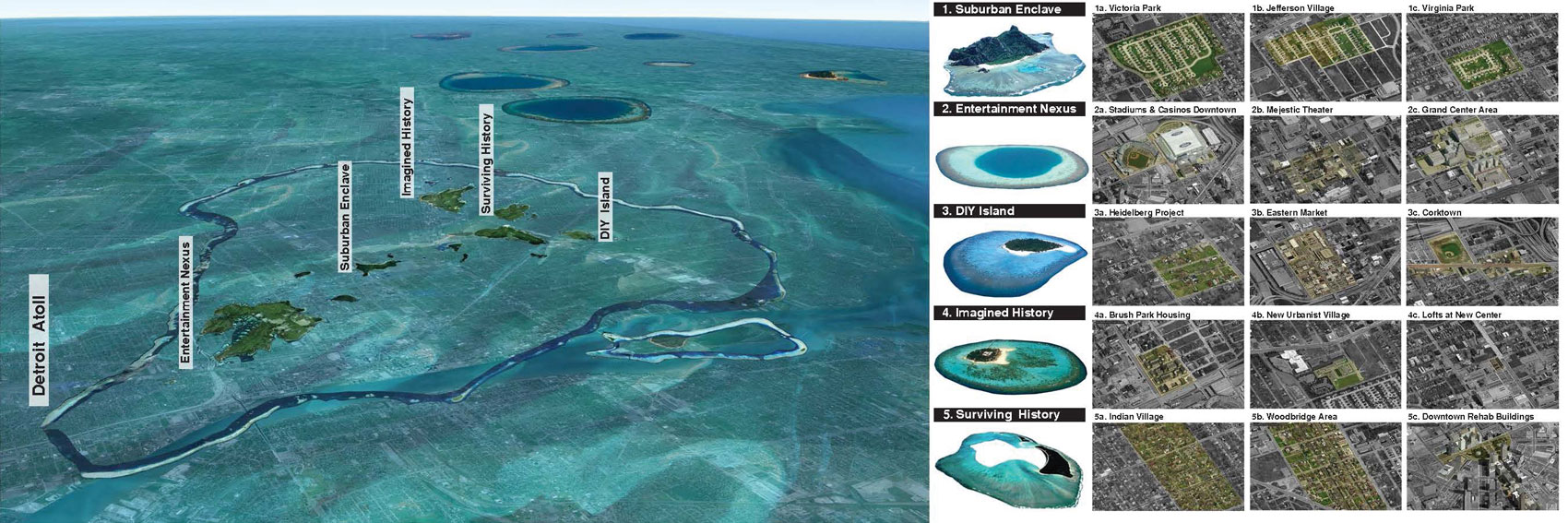

Detroit’s fiscal topography during the boom years of 1990 to 2006 both shaped and was shaped by the city’s series of unique typologies. Together these typologies form a peculiar analogue to the archipelago model proposed for West Berlin by O. M. Ungers in the 1970s.

Unlike Ungers’s proto-postmodernist model, however, Detroit’s does not adhere to any platonic ideal of form, placement, or program.

In the place of Ungers’s ordered and diverse assemblage of forms, presumably sited according to a master designer’s wishes, Detroit offers an opportunistic assemblage of often banal typologies, as cohesive and isolated as Ungers’s but sited according to the city’s peculiar fiscal topography. The city’s typological archipelago is the result of an almost accidental combination of street networks, remnants of historic fabric, surviving social prestige, overlapping layers of public subsidies, and developer inspiration.

Topographical landscapes of wealth and poverty: global peaks of wealth vs. atolls of sinking economies.

The fiscal topography of financial global investment / disinvestment.

The resulting topography is a paradigmatic version of twenty-first century urbanism with which urbanists per se had little to do.

Detroit’s typological archipelago has a long historical lineage. Even as the city completed its early twentieth-century fabric it began to disrupt it with a series of discrete, often widely separated object- buildings. In the 1940s Eliel and Eero Saarinen’s Detroit Civic Center proposal converted the formerly industrial riverfront into a series of monumental auditoriums and public plazas. Much of this design was realized, but in reduced form. Just a decade later Lafayette Park, designed by Mies van der Rohe, Ludwig Hilberseimer, and Alfred Caldwell, converted much of the eastern side of downtown into what Sarah Whiting has called a “figured field,” as much greenery and infrastructure as building. Again, this design was realized only in part. Detroit’s ongoing decline and population loss exacerbated rather than stopped this typological transformation. In the mid-1970s John Portman’s Renaissance Center created a spectacularly isolated and even hostile cluster of towers at the edge of the Detroit River. This self-contained city of offices, hotels, shops, cinemas, and parking lots survives surprisingly intact today as the world headquarters for General Motors. The 1980s brought the largest, but perhaps least celebrated, elements of Detroit’s typological transformation: the mammoth new Poletown and Jefferson North automobile factories, located at the northern and eastern fringes of the city. These generic structures, nearly invisible from the street, were constructed at great public expense for General Motors and Chrysler. Their construction was the epitome of what political scientists John Logan and Harvey Molotch call the public-private “growth machine.”

Each required the condemnation and demolition of hundreds of houses.

Five Design Lessons from the Crisis Era

It is important to note that Detroit’s typological topography developed during a steadily increasing atmosphere of crisis. This crisis culminated in the 1970s, when the city lost over 300,000 people, most of them middle-class whites fleeing a changing racial ratio and industrial job losses, and in the 1980s, when the city allegedly issued only eleven permits for single-family homes the entire decade. The surprising reversal of this crisis atmosphere at the beginning of the 1990s permitted a typological diversification that in turn dramatically altered the city’s fiscal topography, at least for as long as the boom market lasted.

Detroit’s Typological Archipelago: Suburban Enclave / Entertainment Nexus / DIY Island / Imagined History / Surviving History.

At the same time, the products of the 1990s and early 2000s development boom each applied design lessons “learned” from the city’s previous forty years of typological transformation, as follows. The fabric is irrelevant:

If nothing else, Detroit’s decades of postwar decline convinced developers not only that the historic fabric was irrelevant but that it should be removed if at all possible. It is not hard to imagine why: the city’s deteriorating landscape of brick and wooden houses, many abandoned and burned-out, offered a strong disincentive to any form of contextualism. Detroit’s context of ruins reversed the conventional situation for urban architecture, where the surroundings generally offer advantages to adjacent structures. In Detroit isolation from surroundings was the new norm.

Location matters, more than ever: In a prosperous city the usual adage of location, location, location is actually an illusion. London’s Camden Town offers as much value as Belgravia these days, and maybe more. The opposite was true in Detroit, where the distance of only half a block could spell a difference of tens of thousands of dollars in housing value, as well as the difference between a developer’s profit and loss. Detroit’s deterioration meant that location mattered more than ever. As a result, post-1990 development was concentrated only in a few areas: along major streets, in historically prestigious neighbor- hoods, and of course in downtown.

The bigger the better: As a shrinking city, Detroit suffered from too many of what economists call negative externalities—outside factors that depress value. These could be reduced, or even can- celled, by the simple device of scale. A larger development would attract more people, and thereby create a self-contained market that could overcome the externally depressed market of the city. In other words, a big or very big project could act, physically and fiscally, as if the city of Detroit did not exist.

Make the people pay: The money lost collectively by homeowners, developers, and government in Detroit’s decades of decline will likely never be calculated, but it almost certainly numbers in the tens of billions. The result, however, is easily calculated: the numbers of private housing developers willing to construct anything in the city post-1990 without public subsidies (thereby guaranteeing that they would make at least a modicum of profit) was precisely zero.

In Detroit the public paid, even for private development.

Design is a luxury: In the global city, the link between design and finance is close and purposeful. Competition is stiff; design can distinguish one development “product” from another. The same was hardly the case in Detroit’s typological topography. Consumers, developers, and the public sector generally celebrated the existence of any new development at all; design quality mattered little. The result was an archipelago of structures spectacular in scale and dramatic in form but mundane in formal details.

Detroit’s New Typological Topography

These lessons being learned, what were the elements of Detroit’s post-1990 physical topography and how did these new typological elements alter the city’s fiscal topography? The five most prominent examples are summarized below, with each element’s alteration of the fiscal topography shown in the graphic.

The suburban enclave: The lure of the suburbs in a metropolis as decentralized as Detroit is not hard to imagine. Somewhat more surprising is that the growth machine of city and developers constructed several simulacra of suburban subdivisions within Detroit in the 1990s. Located in disinvested yet convenient neighborhoods on the north and east sides, these enclaves of as many as one hundred fifty seven houses applied all five typological lessons in full. They were as financially successful for their developers as they were universally banal in design. Alteration: The enclave’s anticontextualism and large scale created pseudo-suburban islands of prosperity in “close-in” but highly abandoned neighborhoods.

The entertainment nexus: The need for escapism is not hard to imagine for residents of Detroit, where everyday reality could be grueling. And in Detroit’s boom years, suburbanites too were willing to reconsider their abandonment of the city, at least for a night’s entertainment. As part of a national stadium boom, Detroit constructed not one but two new stadiums directly adjoining each other and the downtown (a third stadium for hockey will soon be constructed in this nexus). Combined with three new casinos and two surviving Art Deco theaters, now surrounded by parking, Detroit transformed its once dying downtown into an entertainment nexus. Alteration: Downtown, formerly an office and retail center became something of a party zone housed within monstrous structures controlled by large corporations.

The DIY Island: Post-1990 Detroit, still addicted to big cars and big companies, was far less officially accepting of the “creative class” of artists, musicians, and the like than other cities. This did not suppress cultural activity; rather the city’s high level of abandonment permitted “DIY” (do-it-yourself) islands where the comparative lack of other activity could create cultural districts by default. These could be self-made, as in the spectacular Heidelberg project; ephemeral, as in the city’s 1990s rave culture; or opportunistic, as in the bar districts of Midtown and Michigan Avenue. Alteration: The DIY approach took areas of the city that no one else wanted and made them loci of cultural activity and even modest profits.

The imagined historical fabric: Most of Detroit was constructed between 1900 and 1950, so the city, even at its peak, was hardly the mixed-use, pedestrian-friendly dream of many urban planners. This did not stop some developers from creating imagined versions of the “historic fabric” where there had been none before. In the late 1990s and early 2000s builders constructed lofts and town houses aplenty, with alley parking and even the occasional corner store. The result was the unfinished Portlandization of Detroit—new pedestrian islands amid the surviving Autopian Sea. Alteration: Faux pedestrian pockets in development-friendly stretches of the city north, east, and west of downtown.

The surviving historical fabric: The crisis era of the 1970s and ’80s damaged Detroit badly (as did the post-2007 crisis), but it did not destroy it. All over the city, pockets of historic fabric, enmeshed in the urban grid yet isolated from other healthy neighborhoods, endured waves of abandonment. Survival of the historic fabric required sturdy, united neighbors able and willing to adopt former city services like security, sanitation, and even utilities; the rewards were low-priced, stable, and often beautiful early twentieth-century neighborhoods. Alteration: Fragments of the old Detroit, generally adjacent to prosperous corridors or near the city limits, preserved housing and housing values for middle-class residents willing to stick it out.

Learning from Detroit

The nearly simultaneous death of old Modernism and the liberal state in the late 1970s has meant, at least in the Anglo-American sphere, an ever closer relationship between architecture and finance. This relationship may have reached its latest peak in today’s global cities, but it certainly has not reached its end. In these places architecture’s relationship to capital is all too clear: money not only talks but it buys architecture. In the global city, architecture is an ornament of capital.

The shrinking city offers a somewhat different perspective on this relationship. In a place where capital is mostly absent, architecture’s transformative potential is ironically much greater. Detroit’s bold yet unfulfilled design moves of the most recent boom transformed its fiscal topography in surprising ways. Amid a landscape of increasing abandonment, architecture mattered more than ever. The city’s fiscal topography, its typological archipelago, proved surprisingly malleable to design-induced trans- formations of the urban fabric.

The most recent crisis has sent development in cities like Detroit into a tailspin, and architecture/ urbanism is even lower on the agenda than it was during the boom. In a place where design is perceived as a luxury, interventions will have to be strategic, even subversive, if they are to transgress the still thriving growth machine. Yet design’s transformative potential is great, and some islands in this typological topography are promising. DIY islands are the most open to new ideas, though the least open to profit, while despite persistent calls for change by designers, suburbia remains surprisingly resistant to formal innovation. Another option is that new hybrid typologies will emerge, or that designers will discover other areas of the archipelago—deindustrialized land, abandoned infrastructure? — To explore and perhaps transform into new islands in the shrinking city’s fiscal topography.