Lara Ríos House by F451, Gijón, 2013

The private house was the staging for modernity’s affectation with social, cultural and technological change. During the past century, the domestic space became the conceptual container in which morphological manifestos could travel globally via professional and popular media.

The house had the privileged flair to explore, synthesize, and disseminate the set of questions and expectations that the modern subject was about to face. Is in the modern house—from Loos’ Müller residence to Mies’ Tugendhat—where we encounter the conceptual transformation of the human body experiencing a psychologically liberated space. The twentieth century house was the silent spectator of the ongoing accumulation of industrial commodities and layering of affluent surfaces furnishing the modern subject with a new palette of phenomenal experiences in an increasingly—almost exclusively, I would say—consumer-oriented society. The locus of modern teleology, the isolated house acted as a prosthetic limb for man to explore techno-utopian seductions: think for instance in the expanding and expansive sequence constituted by the House of Tomorrow, the House of the Century, and even the House of the Future, wherever that tomorrow, century, or future was meant to be. Technologies of environmental control permeated within concrete structures, pristine walls, and planes of glass as the century moved along, transforming the psychological map of modern subjects. All these topics and many more found formal expression and accommodation in the limited amount of square feet that the space of the house entails, providing a dense cultural fabric made out of material and intellectual fibers equally revealing and hiding its own ideology. The private house unfolded as the perfect media, the imperative showcase where modernity could exhibit all its enticing eloquence.

If we can think about the domestic space as a recording device—a sensor of the cultural atmosphere pervading society—, a quick look to contemporary production reveals an almost blank document. The house as the original manifesto for young architects to disseminate fundamental ideas for the field and for their future practice seems to be out of tune. With few exceptions, the sharpest statements of emerging practices have neglected the cultural prospectus of the individual—or the diverse contemporary family—to concentrate instead in ephemeral performances, conceptual installations, or temporal exhibitions, that is, in social and institutional events that, like the economy of tweeters, travel fast with little expenditure. One could say that currently, we find the most interesting results for the future of the field present at the intersection between architecture and art practices. Thus, despite the proliferation of more or less compelling designs—the bamboozling parade of formal contributions for the Ordos 100 urban design project in Inner Mongolia comes to mind—the field seems to be short of profound reconsiderations of issues involving domesticity for the post-industrial subject. Perhaps more juicy statements will emerge after the ‘uncompromised’ curatorial series of the Solo Houses in Mataranya, Teruel, where the contributions of Office—Kersten Geers and David Van Severen—, Sou Fujimoto, Mauricio Pezo and Sofia Von Ellrichshausen, and MOS—Hillary Sample and Michael Meredith—to name just a few, promise to challenge some of the formal and programmatic ideas generating the house. However, this business-oriented model together with the marketing strategies of the promoters should put criticism on ward. On the other hand, contemporary criticism is not paying enough attention to the isolated house. And yet, to speak about the single private house is to speak about the fundamental multiplicity of conceptual topologies influencing the field. The domestic house is an uncharted battlefield of cultural conflicts and anthropological manifestations that perhaps deserves a closer reading than the one supplied by current commentators.

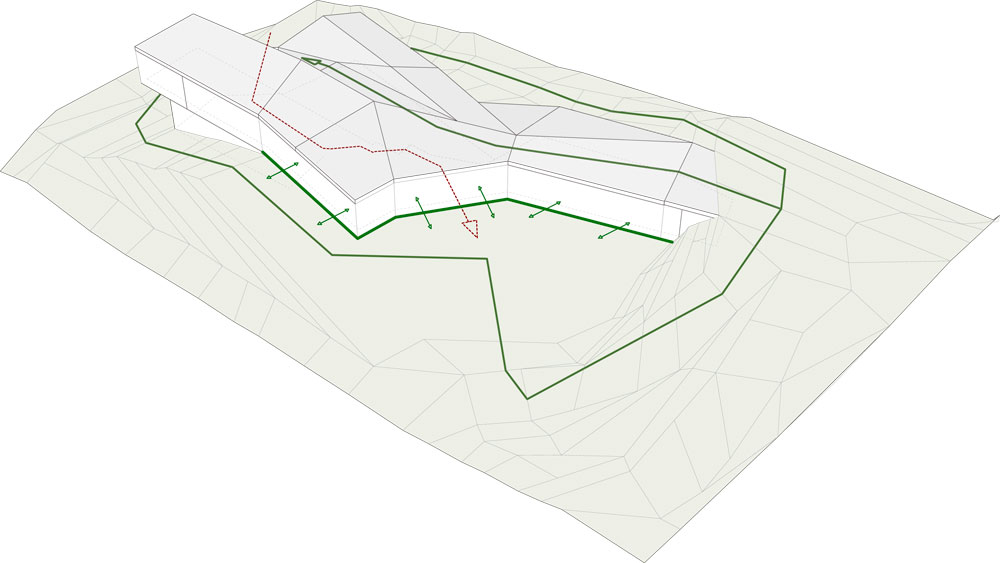

Among the most interesting contributions to the recent domestic debate we find a house designed by the Barcelonese team f451 for the painter and sculptor Lara Ríos in Gijón, North Spain. This house provides an opportunity to think about the always-difficult relation between architecture, culture, and material expression.[1] Following biographical contingencies, the house represents an end as well as a departing point that corresponds, perhaps too well, with contemporary uncertainties about the stamina of past theoretical and critical models. In the Lara Ríos House, one can feel the materialization of larger disciplinary debates taking place during the last two decades. And nonetheless, the set of influences and multiple references that this object brings about are perhaps in need of thorough revision and assessment in order to understand the critical potential of architectural form.[2] A close look to the skillful combination of triangular planes, white functional folds, and gestural landscaping accommodating the different programs in the house will help us to reconsider the impact of sustainability and representation in the private sphere as well as in the field at large: eventually, the house appears entrenched in the meta-field conditions of its own historical existence. The triple formal indeterminacy helps us to unveil some of the underlying assumptions with which architecture operates.

Lara Ríos House by F451, Gijón, 2013

The Machine in the Garden: A Triple In-Between(ness)

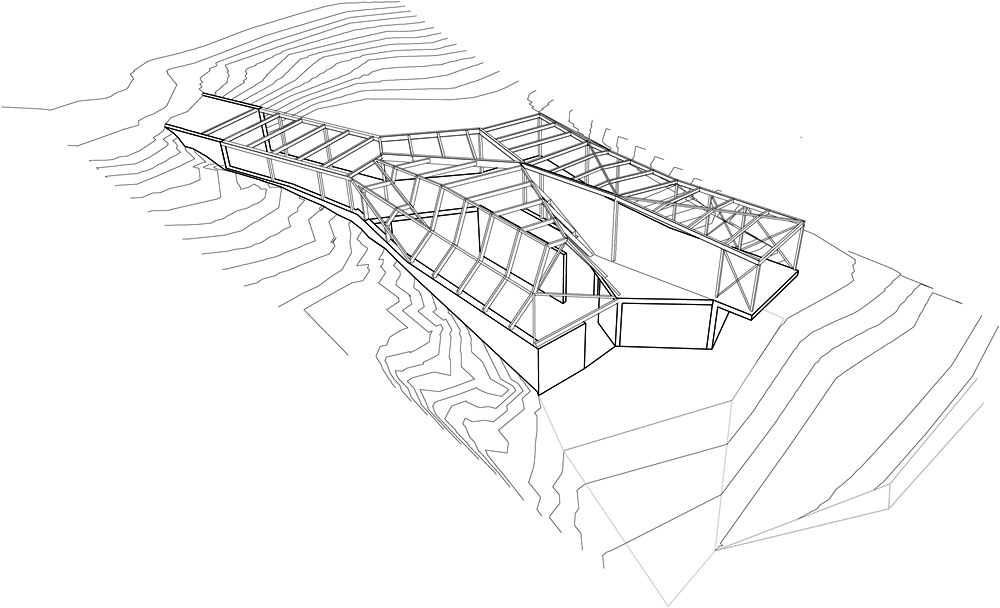

Designed amidst a global economic crisis that had its European overtones, the house proposes an expressive, sculptural formal solution based in skillful combinations of geometry and surface maximizing the meager means and techniques available. In the site, the Lara Rios House performs as a stubborn statement against mimetic contextualism, favoring landscape manipulation without falling into facile manicures. Far from an exercise on escapism or calculated condescendence towards the complicated articulation of functional requirements, this house promises a multiplicity of never ending roads: the formal programmatic gestures within the house culminate a decade of renewed interest in the temporality of tectonics and its geological metaphors. Whether label as “landscape architecture,” a miniaturized version of landscape urbanism, or yet another iteration in landforming buildings, the house bespeaks about the capacity of its architects to evolve from their intellectual genealogies, originating in the impact of computers in architectural design, to partake in the dialectic game of responses to contemporary discussions. However, let’s consider first how the house materially engages in these formal debates and how the original requirements—the construction of a house with a space for guests and an atelier—have been interlocked. I would claim that this domestic space deals with the existing topography through a strategic triple ‘in-between-ness.” Only then, the formal indeterminacy of the object becomes useful to understand the critical dimension of the final solution.

Lara Ríos House by F451, Gijón, 2013

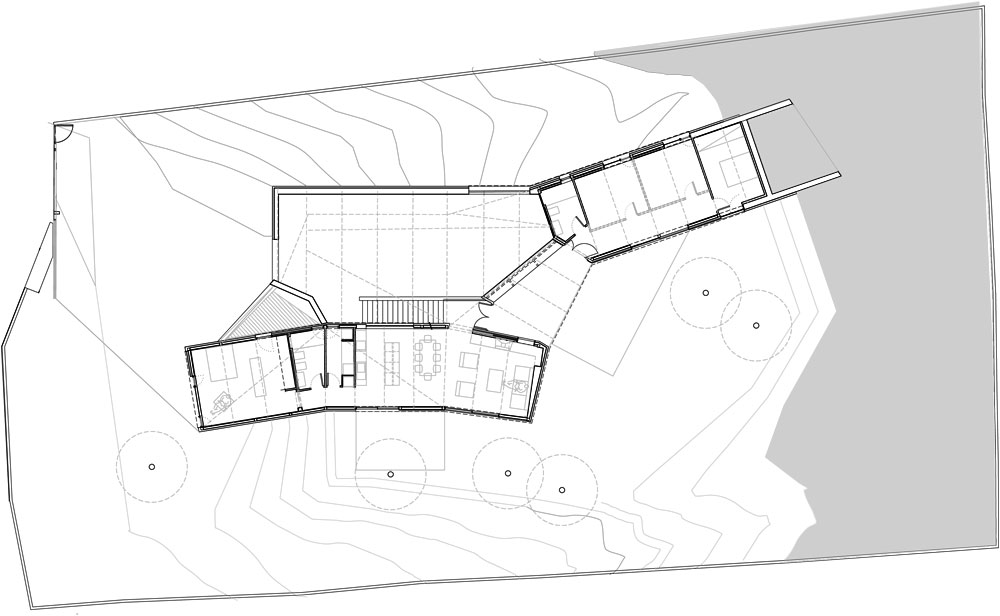

A simple geometrical move ends up determining the perceptual reading of the house: its morphology entertains the program between the ground and the extended landscape. The Lara Ríos House evolves beyond whimsical origami’s folds to situate the space of the domestic in different levels of the original plot. This decision does not depart from composition but from volumetric organization. And yet, in so doing, it provides a classic triple level to experience the house: the ground—base—, the building—shaft—, and the accessible roof—crowning. It would have been perhaps too easy to reinforce the geographical metaphor in the final election of materials. But the whiteness of its walls and the simplicity of the openings relates the solution to its modern origins: camouflaged beneath the green roof we’ll find a contemporary reinterpretation of the modern ‘duck’, the self-justified index of a methodological—i.e., stylistic—approach to architecture. Contesting the infatuation for new materiality in its digital form, the combination of whitewashed walls and green tapestry in the Lara Ríos house titillates between the tactical manipulation of matter and the larger tradition of artificial surface aloofness. Eventually, the house is about combining material realism and surface abstraction: once matter has been proved docile to the demands of the architect and the possibilities of machine production, perhaps it does not make sense to continue humiliating the resources that nature provides with unnecessary decorations. Thus, the silent white walls of the Lara Ríos speak loud, responding with a clinical distance to the ubiquitous presence of images, patterns, and textures eating away contemporary façades. The pristine surfaces as unveiled by the geometrical gestures reminiscent of simplified geological process, relate to environmental economy: the white stucco skin and the green textile of the roof protect the thermal clay insulating blocks creating the proper conditions for habitation inside with minimum expenditure. In addition, volumetric differentiation allows for spaces of transitions, like the roofed exterior vestibule located in the center of the house. This area, original of Arabic traditional architecture—the istawan—, has its own agency in the energetic interchange between exterior and interior. With its accommodation in the overall distribution, the formal organization regulates energy consumption and production while negotiating the topographical levels: a formal and material sustainabilitas claiming for validation between the dustier firmitas and utilitas.

Lara Ríos House by F451, Gijón, 2013

Secondly, the house’s type oscillates between the space for labor and the space for intimacy. It is a pressing necessity in current societies to expand the room devoted to professional activities within the domestic space. Although the intrinsic nature of the commission—a studio for an sculptor—claimed for a large space adjacent to the main body of the house, the final solution is that of connected isolation, to use Tom Mayne’s terminology. This relational autonomy supplies a very interesting discursive instrument. A closer examination of the building’s plan and section as relational tools shows the resistance to interact of these two spheres since the articulation between both programs is not produced in the technicalities of the plan but in the complex relationship with the roofing. However, labor takes the lead in representational matters: the type of the factory, although whitened, imposes its logic from the very beginning, filtering the arrival to the house through an industrial—inflated if you want—, foyer. As such, both programs remain autonomously attached. If Robin Evans underscored the emergence of the corridor as a problem of secluded carnality, the promiscuous presence of labor in the space of domesticity pinpoints the seamless condition between both: dwelling and working are getting closer and closer, almost indistinguishable one from the other. Actually, the roof of the atelier unfolds again towards the east to reach the guesthouse, as if not a single corner could scape from its sphere of epistemological influence.

Lara Ríos House Structure diagram by F451, Gijón, 2013

Lara Ríos House Plan by F451, Gijón, 2013

The articulation of volumes and programs in the house illustrates the social conditions under which labor operates in capitalist societies. Indeed, the continuity between work and domesticity did provide multiple historic housing types where artisans and small businesses organized their activities in the same buildings they inhabited. And yet, the detachment of the house from the urban fabric as a social continuum in the Lara Ríos House indicates a new installment in the ever-changing relation between labor, production, distribution, and consumption. A consequence of that detachment is the evolution of some programmatic features: between the three programs, emerges the above-mentioned istawan, a symbolic element that formerly negotiated the private and the public domain right at the very entrance of urban residences. Instead, this threshold of historic reminiscences has been left aside in the Lara Ríos House, becoming a lateral adjacency away from the domain of the street. It remains metamorphosed as a static regulator of climatic conditions between the parts, completely divested of its former social connotations. However, despite its downgraded representational status, it emerges as a central element in the articulation of the different volumes: from it we can still gain access to the three different spheres—the domestic sphere, the social sphere, and the sphere of labor. This centrality has been acquired at the expense of the urban dimension: An undeveloped limb with a renewed function, this istawan seems unwilling to remain attached to the urban tissue. If European postmodernism subordinated the former modernism’s emphasis on entrance and access to iconographic identification in major buildings—I challenge the reader to mentally recall this moments in the continuous skins of OMA’s CCTV in Beijing or Herzog & de Meuron’s Eberswalde Library—the symptomatic displacement of the entrance in the Lara Rios House tells the story of a difficult relation between public and private that has in contemporary architecture production another material episode. After all, as digital media constantly remind us, sociability begins with labor. Few times we can enjoy the symptoms of a type evolution in such a clear way as in this small commission in Gijón.

Lara Ríos House by F451, Gijón, 2013

Still a third condition: despite this initial detachment, the house still stubbornly vindicates a position between the object and the urban project in the formal repertoire of the architects. Responding to a different scale, the building replicates the formal and methodological strategies developed previously by the office in different contexts: from institutional gestures, to public infrastructures. For instance, in the picnic area developed for the Universitat Pompeu Fabra in Barcelona (2009), the architects materialized a formal language in relation to landscape based in minute geometric movements and folds that found continuity in the winning entry for the new ferry terminal in the city of Maó, Menorca (2009). The Lara Rios House’s genealogy, occupies an intermediate position between both: an overdeveloped bench or a minimized public facility. This identification between the micro and the macro scale—the scale of the object and the scale of the city—places the work of the designers in a total continuity, reawakening the old Ernesto Nathan Rogers’ postwar motto “from the spoon to the city”—following Muthesius—, giving continuity to the work of the architect beyond disciplinary self-imposed constrains. As such, the house becomes another link in the construction of the project in an epistemological sense: the designer and the planner, the detail and the whole, working together to materialize an idea of architecture. After all, these design activities require all similar analytical skills and material expertise. However, the investment in formal coherence has its own limits: triangulations and folds consume larges amount of public space to make them fully operative. In the case of the Lara Rious House, the material consumption of landscape turns into instances of camouflage, burying partially the program and helping extending the garden over the rooftop.

Lara Ríos House by F451, Gijón, 2013

But what this triple intermittence—between ground and landscape, between labor and habitation, and between the micro and the macro scale—has to say about contemporary conditions of domestic space production? How this morphology translates into a meaningful reading of society beyond the detection of conspicuous and unassailable stylistic lineages? If the literality of metaphors, diagrams and gestures brought about a new kind of architectural realism during the early 1990s, the naturalization in the use of software for architectural production by architects during the last decade allowed them to interconnect the multiple autonomies in the design process to make them effective and affective as the “projective” clique asked for. Besides the artificiality of the critical / post-critical dialogue in which several young practices emerged—and the biography of f451 indeed partakes of that cultural atmosphere—, the effectiveness of the architectural object could not be measured against aesthetic standards but against collective and political ones. Or, to put it otherwise, there were low expectations about aesthetics in architecture. It is only in its capacity to interpret and materialize larger social and political anxieties where architecture becomes seriously effective. At this point, to question the management, production, and location of architecture in its material relation to the urban context seems unavoidable.

Enjoy your Symptoms

The use of computers inaugurating the post-industrial age allowed architects to define landscape as simply another object among the myriad of our consumer’s environment, controlling every minute modification of its geometry, aspect, and performance. In this linage, the Lara Rios house transmits the idea of a manipulated plot, an unnatural site where nothing has been left to randomness. The fabrication of landscape has significant consequences for traditional understandings between form and content. The former distinction between kunst–form or art-form as represented by the building’s final epidermis dressing a structural core-form dissolves as soon as we deal with earth arrangements. What the post-industrial landscape of public space has achieved is the repositioning of classical nineteenth century tectonics, collapsing core-forms and art-forms in the public sphere: the topography as finally accountable for the sculptural expression of architectural interventions. Examples in that respect abound in the architecture of Weiss Manfredi, UN Studio, or FOA—Wasn’t the lower level of the celebrated project in Agadir by OMA a foretaste of that synthesis?

Bonga House by Erwin Broner, Santa Eulària del Riu, Ibiza, 1963

Bonga House by Erwin Broner, Santa Eulària del Riu, Ibiza, 1963

It is at this point historically convenient to recall the architecture of the globetrotter Erwin Broner to illustrate the transition in landscaping taking place in Spanish contemporary architecture. After travelling from Germany to the United States—where he built several houses and worked as stage designer for Hollywood—, he ended up rooting his practice in Ibiza in the late 1950s. During the 1960s he built his reputation with a series of white-washed houses in the island—often with rusticated stones in the ground à la Breuer—that arguably influenced the earlier works of the office Elías Torres and José Antonio Martínez Lapeña, allegedly among the most vociferous proponents of a landscape-oriented attitude towards design within the older generation of Spanish architects.[3] The houses Broner designed during the 1950s have among their most conspicuous motifs the placement of exterior stair accesses to their roofs, converted into occasional terraces for visual enjoyment over the interior ridges or the Mediterranean Sea. The access to that privileged space is visually explicit through the stair element that relies on vernacular optimization and social contracts. One could say that the house is actually the one hanging from the stair, as if the need to view the landscape preceded the need for habitation. In contrast to these mid-century strategies, the formal gestures of the Lara Ríos House positions the visitor in a continuous green textile that culminates on top of the house. The transition in the vertical axis becomes almost unnoticed, conquering the house effortlessly. At this stage, the possibility for social gatherings and further views appeared as neglected: the mat of the roof is not the signifier of the landscape but the signified itself. There is not a space to be conquered but just an image to be distributed: the green roof appears as the very media that unveils the postmodern circumstance organizing the house.

Landscape architecture is often recognizable by the smooth field of planes and angles transiting seamlessly from one level to the other, usually through highly nuanced triangulations and folds. With horizontal landforms we are witnessing a transformation of traditional landscape architecture: a French jardins without governing axis, or an overt picturesque garden where the surprise element has been suppressed. If nothing, it just refers to urban spectacle. And that quality is what makes those architectures so postmodern: as Frederic Jameson and Slavoj Žižek insist upon, the explicitness of the sign and the ‘flatness’ of the argument emptied of double meaning—so evident in current film production where there is no room left for interpretation—, is ultimately what sustains the commercial project. As the house reveals, landscape architecture—the rise of landscape architecture was always a urban project—attaches the garden to the machine revealing all its artificiality. It provides a natural patina, a green ersatz cladding the outdated modern project. The folded surfaces and the multiplicity of geometries hide the fact that the path has already been established and there is little space for individual agency. In return, these manipulations promise a dynamic experience—maybe ‘cool’, maybe not—that are visually rather than physically oriented. Only then, nature and its textural associations become ornamental.

Eventually, landscape architecture animating the interstices and marginal areas of former industrial districts rejected the city in the terms in which it had been historically formulated. In this house, we are facing a conceptual, methodological, and morphological import from urban strategies of re-appropriation into the limits of the domestic. This is a very significant transference, speaking about the continuity of our built environment and the intellectual frameworks in which architects operate. Exists a centripetal force that drives the urban concerns of modernity towards the house and that has been silently taking place during the last half century. First was the space for leisure; then the space for labor; finally, the space for communication, rendering transportation simply optional: the four points constituting the Athens Chart to organize contemporary cities have been quietly gravitating towards the space of the single house. In this light, the formal dynamism of many contemporary solutions to the problem of domesticity is ultimately deceptive: it stands as the material counterpoint for a subject that no longer has the need to move. As the tail of a lizard moving mechanically before life banishes, formal dislocations in architecture—and the following applies also to blobs, folds, and miscellaneous dynamic surfaces—conceal a conspicuous truth in contemporary societies: if twentieth century was about accelerating subjects, the first years of the second decade in twenty-first one seem to be about decelerating them. On the one hand, the exhaustion of natural resources and the uneven social solutions to the Great Recession are putting economic boundaries to the democratization of travel and leisure, particularly in South Europe. On the other, the development of technologies of communication is accounted responsible for enlarging the cliff between subjects, experience, and nature: shopping, working, bureaucracy, dating, sightseeing, banking, culture, information, and education are simply available with the click of a mouse. We are replacing experience for visual excitement within a reality that only has a deceptive tactile appearance in our computers, tablets, and smart phones. Is in this context where we can think about a moment of conclusion of the tradition of landscape architecture as a urban project. What began as model for urban appropriation of the former industrial past, ended up crystalizing in the space of the domestic, dramatically curving its own surfaces for the sake of representation. At this point, only metaphors and geological rhetoric remain. Perhaps it is time to bring back the urban experience to the drafting table in material, social and political terms. Perhaps it is the moment to propose a different urban model by rethinking the adequacy of traditional tools informing architecture’s expertise. Perhaps becomes urgent to acknowledge the fact that, despite past utopian frustrations, architecture can do much more to respond to the pressing problems facing contemporary cities.