The port of Beirut is an island – Standing as a logistical agglomeration along the northern coastal edge of the city, this infrastructural mass comprises wide quays, hangars, storage depots, and container yards, forming a boundary between the city and the sea. However, the relationship between the port and the city was not always one of division.

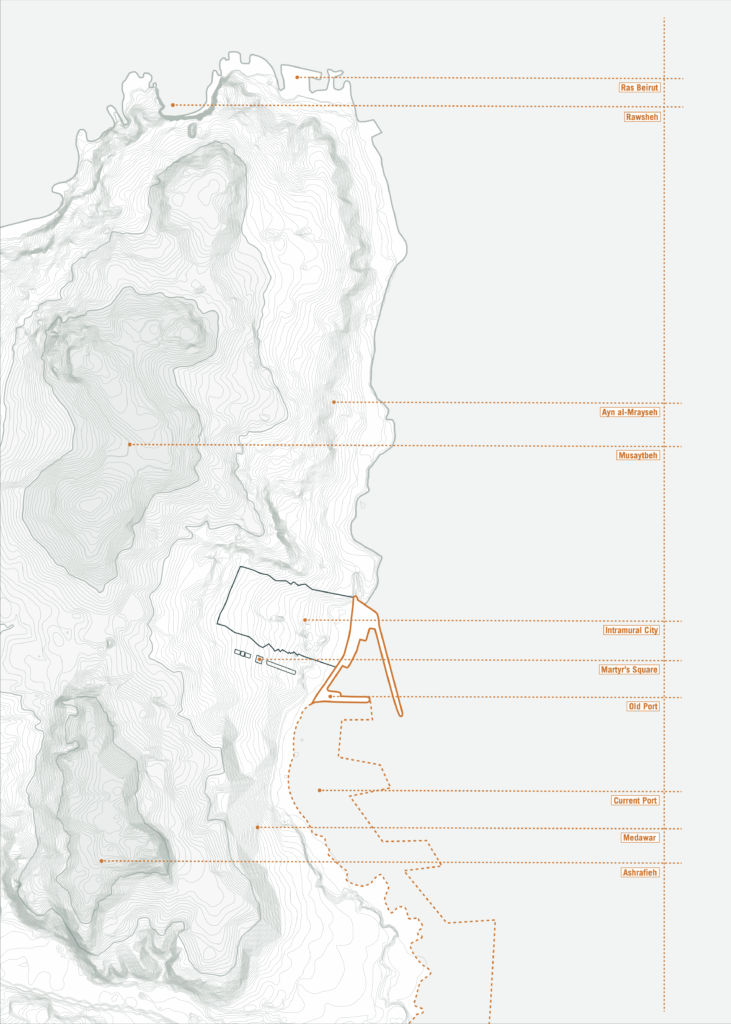

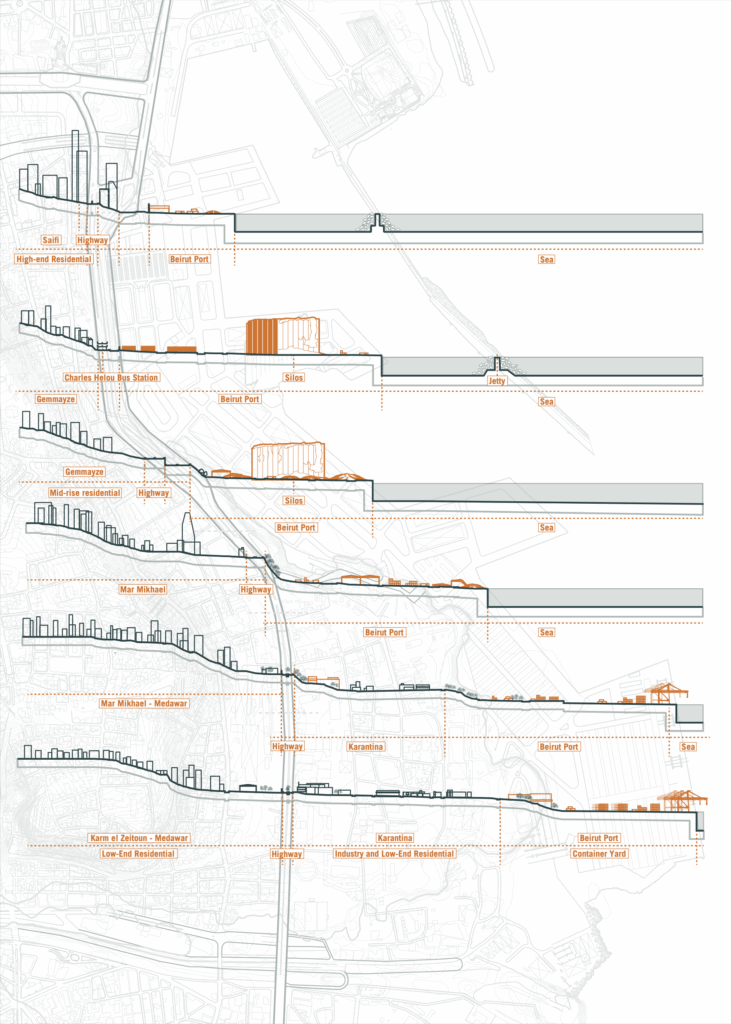

Geographically located at the northern side of the peninsula of Beirut, the port historically took advantage of this natural coastal edge that offered protection from southern sea winds and allowed ships to find refuge. Nestled between the hills of Ashrafieh and Musaytbeh, the old intramural city extended down to its port and natural coastline [1], with its eastern wall running parallel to an open plateau, the ‘maidan’, later known as Place des Canons or Martyrs’ Square. The natural connection between the port, the city, and the maidan formed a vital artery that linked the sea, the city, and the surrounding region. East of the maidan, the elevated Saifi cliff created a physical barrier with the sea, delineating the port’s eventual expansion. This topographical shift and later development of the coastal highway further reinforced isolation and disconnection between the port and its immediate neighborhoods.

Historical evidence indicates the presence of Beirut’s port since Greek and Roman times [2]. However, its most significant expansion occurred in the latter half of the nineteenth century, coinciding with a surge in trade. The economic boom in Europe between 1848 and 1873, alongside the opening of the Suez Canal in 1869, shifted global trade dynamics toward the Mediterranean. French and British colonial powers vied for control during this period [3], which led to the port’s expansion under French influence. Parallel developments, such as the establishment of railway infrastructure and the opening of the Damascus Road, which intersects with the maidan, further reinforced the port’s regional and national significance [4].

As the city expanded, eastern neighborhoods like Saifi and Rmeil developed in tandem with the port, facilitating the movement of people, goods, and trade. This growth attracted a diverse population seeking employment in port-related activities and the emerging service sector, leading to the rise of a mercantile community [5].

The port during this late Ottoman period was more than a quay for trade; it obtained a hybrid nature that formed a natural extension of the old city and incorporated khans, locandas, a department store, and a bank [6]. While the maidan plateau was separated from direct access to the sea by a cemetery, secondary connections facilitated its growth as a vibrant marketplace and travel hub closely linked to the port. The synergy among the port, the city, and the region persisted throughout the French mandate and into the early years of the Lebanese Republic, continually supported by the urban morphology and geography of the city.

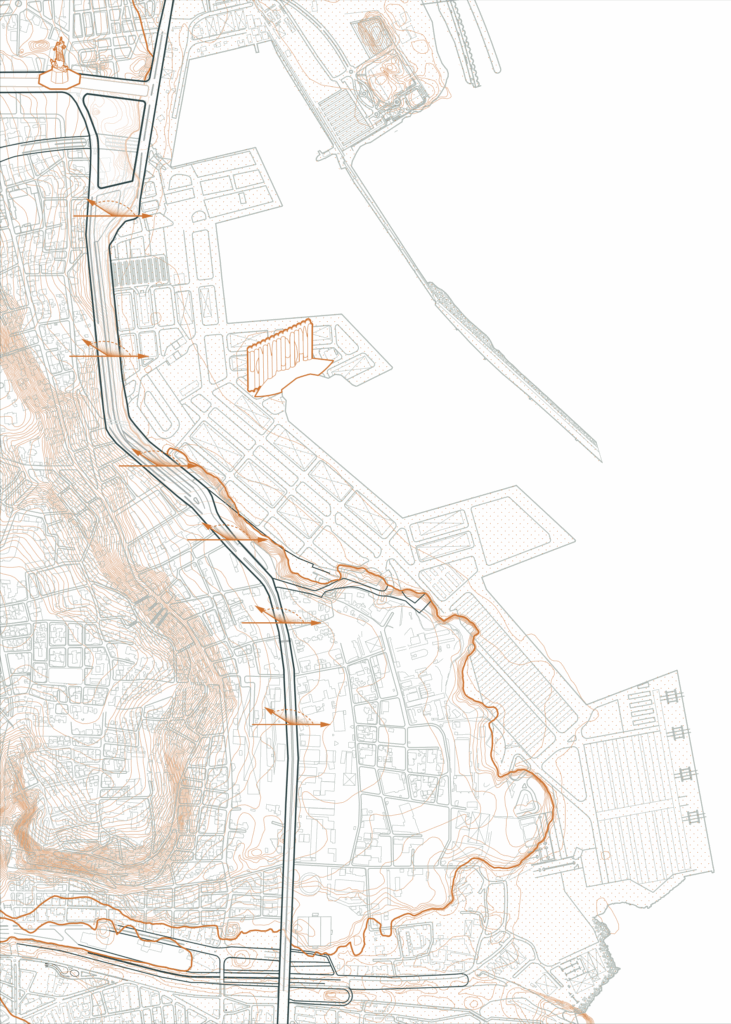

Modern expansion and eastward growth of the port benefited from the natural elevated topography which helped buffer it from direct urban connections. The construction of the Charles Helou highway and bus station in the early 1970s further reinforced this separation from the city [7]. The Civil War marked a significant decline in the port’s operations and its role in the city’s economic growth, as infrastructure suffered substantial damage. Trade and shipping were affected, and many businesses relocated away from Beirut. Even after the war ended, it took years for port operations to fully resume. The reconstruction of the downtown area of Beirut shifted the port’s main entrance and first quay further east, moving it away from its historical core and disconnecting it from Martyrs’ Square.

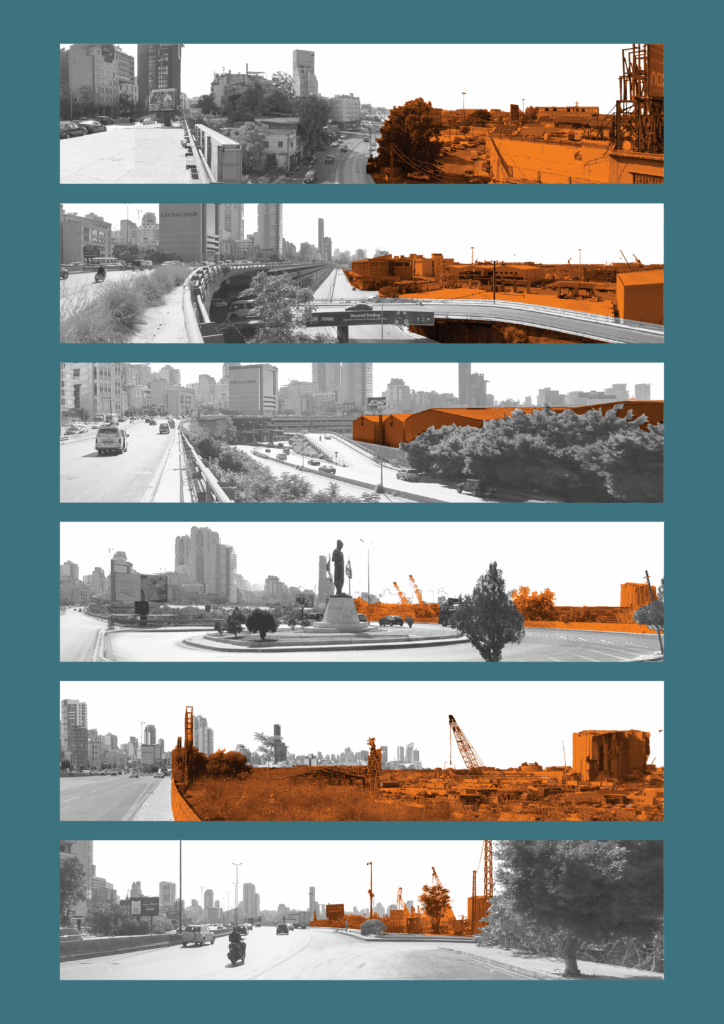

As a result, the port and city evolved as two distinct entities. While the port remained a part of the city’s identity, it became a distant memory of its former prominence. The August 2020 explosion starkly exposed the port’s proximity to the city. The Port Silos have since emerged as a new ‘commons’, symbolizing shared trauma and recovery. The blast not only damaged the port and the city but also metaphorically unveiled the once-forgotten relationship between the city and the sea, transforming the logistical port ground into a barren backdrop against the highway.

Today, discussions about post-blast reconstruction continue to explore the relationship between the city and its port. Urbanists advocate for an open port policy, through a memorial and a reimagined connection to the sea, while politicians and global shipping agglomerates favor maintaining a separation between city life and the port’s operations.

In this context, the port holds a paradoxical identity; while it once represented a thriving economic hub for the city, it now symbolizes destruction and the conflict between operational demands and urban needs. The silos, once symbols of abundance and modernity, have become blatant reminders of shared trauma, their presence marked by the crater left by the blast—a physical indent in the ground and a symbolic wound that lingers in the collective memory.