The Beyond Patronage symposium was a thought-provoking day with a series of all-woman panels comprised of an array of design research and creative practices demonstrating what beyond patronage architectural practices look like. And that the day’s events only included women is critically important and must be acknowledged. The theme of the symposium and, by extension, the book is such a timely topic. Publicly discussing what beyond patronage means, in order for the profession to evolve and be more responsive to our contemporary society, is of utmost importance today.

When I began to think about what moving beyond patronage means, I could not help but think about the connection between gender and architecture. In my mind, when patronage and architecture are spoken about together, gender is inextricably a part of this relationship. I do not believe we can speak about moving beyond patronage without acknowledging and addressing issues of gender and architecture too.

When considering ways the Beyond Patronage symposium intersects with my own work, I came across an essay by two men entitled, “What About the Men? Why Our Gender System Sucks for Men, Too.” One issue they discussed was the idea of privilege, and that it is invisible for those who have it. [1] As I begin this essay, I would like to ask you, the reader, to think about what this word represents; about ways privilege is touted or even camouflaged, politically and culturally. So often these two terms—privilege and patronage—are interchangeable and quite interconnected. What forms do your own patronage and privilege take?

Where are you from? What color is your skin?

Where are or were you educated?

What do your parents do? Your grandparents?

How do you begin to recognize your own patronage and privilege and all the associations and connections these include?

The image I begin with is of Philip Johnson’s 90th Birthday Celebration at the Four Seasons Restaurant in New York on July 9, 1996. Philip Johnson could be considered the grandfather of 20th century architectural patronage, connecting rising and risen stars with astounding clients and commissions. You will notice all of the ‘star’ architects of the day. Seated on the floor are Peter Eisenman and Jacquelin Robertson; in the first row are Michael Graves, Arata Isozaki, Philip Johnson, Phyllis Bronfman Lambert, and Richard Meier; in the second row are Zaha Hadid, Robert A.M. Stern, Hans Hollein, Stanley Tigerman, Henry Cobb, and Kevin Roche; and in the third row are Charles Gwathmey, Terrence Riley, David Childs, Frank O. Gehry, and Rem Koolhaas.

The woman seated directly to Johnson’s left is Phyllis Bronfman Lambert of the Bronfman family fortune that includes the Seagram distillery business. She is a patroness in her own right. Formally trained as an architect at the Illinois Institute of Technology, she was instrumental in inviting Mies van der Rohe to become architect and collaborator with Philip Johnson for the design of the Seagram Building, the headquarters for the Canadian distiller, Seagram’s, where her father was CEO. [2] She also founded the Canadian Centre for Architecture in Montreal, Canada, in 1979. As their website mentions, “The CCA was conceived as a new form of cultural institution to build public awareness of the role of architecture in society, to promote scholarly research in the field, and to stimulate innovation in design practice…and is devoted to interdisciplinary research in all aspects of architectural thought and practice.” [3]

What does beyond patronage mean for architecture? How can this be a new model for the future of our profession? I saw this symposium—and now book—as an extension to the larger discussion regarding the ramifications of what moving beyond patronage is actually asking; questioning the construct of how we teach, how we learn, and how we practice architecture; a model that has had very little change for well over a century. Beyond Patronage is a critique of this system and the ongoing status quo of architecture. This book provides critical alternatives to the system of patronage that architecture has relied on since its founding, ideas about how to seek work that people are committed to and truly invested in pursuing, and insights into possibilities of accessing new client bases and publics for engagement.

Architectural patronage

This essay will first highlight two obvious forms of patronage practices in architecture; next, zoom out in scale to position the ideas inherent within the book in a larger social, political, and economic context; and then conclude by speaking more directly to our profession, positing ideas of moving beyond patronage.

The first form of patronage I would like to highlight is the Pritzker Architectural Prize. The prize gets its name from the Pritzker family, whose international business includes Hyatt Hotels. Based upon the Nobel Prize, Pritzker laureates receive a $100,000 grant, a certificate of citation, and, since 1987, a bronze medallion. [4] As their website states, “The prize is awarded irrespective of nationality, race, creed, or ideology.” [5] The nominating process “actively solicits nominations from past laureates, architects, academics, critics, politicians, professionals involved in cultural endeavors and with expertise and interest in the field of architecture… Nominations are accepted internationally from people in diverse fields who have a knowledge of and interest in advancing great architecture… Additionally, any licensed architect may submit a nomination for consideration.” [6]

Since 1979, the Pritzker Prize has been awarded to 39 architects. Two years have included firms: Herzog and De Meuron in 2001, and SANAA (with Sejima and Nishizawa) in 2010. [7] Of these, only two have been women—a mere 5% of all architects awarded. If we expand this to actually include Denise Scott Brown of Venturi Scott Brown and Lu Wenyu, the partner with Wang Shu of Amateur Architecture Studio, the 2012 laureate, we would double women’s awards. The fact that these women were not included, and that there have not been more women and people of color awarded the Pritzker Prize, is a clear reflection of patronage and privilege at work. Since the Beyond Patronage symposium in October 2012, there has been much publicity on this issue, including a Change.org petition by Women in Design, a student organization of Harvard’s Graduate School of Design, asking the Pritzker committee to retroactively recognize Denise Scott Brown with her partner and husband Robert Venturi, as he was solely awarded the prize in 1991. Although the petition garnered over 19,000 signatures, the Pritzker Committee declined to give Scott Brown the recognition she so clearly deserves. [8]

The second example is the American Institute of Architects Fellow award. The FAIA “was developed to elevate those architects who have made a significant contribution to architecture and society, and who have achieved a standard of excellence in the profession. Election to fellowship not only recognizes the achievements of architects as individuals, but also their significant contribution to architecture and society on a national level… Out of a total AIA membership of over 80,000, there are over 3,000 members distinguished with this honor.” [9] Of the 105 AIA members who became fellows in 2012, only 19 were women, roughly 18%, or slightly three times more than those awarded Pritzker Prizes. Of the 105 fellows, three were African American men, 2%, compared to only one African American woman, or just 0.9% awarded. Clearly, this is inadequate recognition for women or people of color in our profession. Although representation is higher than 50 years ago, explicit patronage is alive and well in both our discipline and our professional organizations.

Contextualizing 2012

Whether serendipitous or not, the timing of Beyond Patronage could not have been more in sync with current events. There is a movement afoot with a critical mass, beginning to speak louder and louder, gaining traction across a broad spectrum of issues concerning equity and social justice. I think this is important because a critical mass has more power to effect and force change. I would like to highlight two events that I believe reflect a cultural pulse that contextualizes the broader issues this symposium and book raise and serve as important parallels to Beyond Patronage.

In January of 2012, the Obama administration mandated, “most health insurance plans must cover contraceptives for women free of charge,” refusing the Roman Catholic Church’s proposed religious exemption. [10] Not even one month later, after receiving strong backlash from religious groups, the administration announced a compromise requiring the “insurer—rather than the employer—to provide contraceptive coverage.” [11] This announcement precipitated a House of Representatives Oversight and Government Reform committee hearing. One of the most distressing and outrageous aspects of the first hearing was that the coterie of witnesses included only five men of various religious and academic affiliations. Women in support of contraceptive coverage were not allowed to testify. [12] As committee chairman, Representative Darrell Issa tried to argue, “The hearing is not about reproductive rights and contraception, but instead about the Administration’s actions as they related to freedom of religion and conscience.” [13] Committee member Representative Carolyn Maloney (D-NY) asked, “What I want to know is, where are the women? … I look at this panel [of witnesses], and I don’t see one single individual representing the tens of millions of women across the country who want and need insurance coverage for basic preventive health care services, including family planning.” [14] In objection, Representatives Maloney (D-NY) and Eleanor Holmes Norton (D-DC) walked out. [15]

House of Representatives Oversight and Government Reform Committee Hearing, Lines Crossed: Separation of Church and State. Has the Obama Administration Trampled on Freedom of Religion and Freedom of Conscience?, US Government

Jumping to the summer of 2012, probably the most widely read article that year that precipitated an avalanche in both print and online journalism was Anne-Marie Slaughter’s essay in the July/August issue of The Atlantic, “Why Women Still Can’t Have it All.” [16] Slaughter was the first woman director of policy planning at the State Department, under former Secretary of State Hillary Clinton from 2009-2011, and was dean of Princeton University’s Woodrow Wilson School of International Relations. She is currently the Bert G. Kerstetter ’66 University Professor Emerita of Politics and International Affairs at Princeton University. Her article stems from her own experience juggling an incredibly successful career in academia and government along with immense personal difficulties she experienced while at the State Department, when issues arose with one of her teenage sons at home. She wrote the article because, as she states, “When many members of the younger generation have stopped listening, on the grounds that glibly repeating, ‘You can have it all,’ is simply airbrushing reality, it is time to talk.” She continues, “I still strongly believe that women can ‘have it all’…But not today, not with the way America’s economy and society are currently structured. My experiences over the past three years … forced me to confront a number of uncomfortable facts that need to be widely acknowledged—and quickly changed.” [17] She quotes authors Kerry Rubin and Lia Macko of Midlife Crisis at 30. Their research found, “while the empowerment part of the equation has been loudly celebrated, there has been very little honest discussions among women of our age about the real barriers and flaws that still exist in the system, despite the opportunities we inherited.” [18]

The Atlantic cover for July / August 2012, The Atlantic

Slaughter argues that “[t]he best hope for improving the lot of all women, and for closing … a ‘new gender gap’—measured by well-being rather than wages—is to close the leadership gap: to elect a woman president and 50 women senators; to ensure that women are equally represented in the ranks of corporate executives and judicial leaders. Only when women wield power in sufficient numbers will we create a society that genuinely works for all women. That will be a society that works for everyone.” [19] Slaughter advocates that, in order for better balance to exist, several key factors must change. The three ideas I find most relevant for architecture are the following:

1. Changing the culture of face time — One that we in architecture can clearly identify with.

“The culture of ‘time macho’—a relentless competition to work harder, stay later, pull more all-nighters, travel around the world, and bill the extra hours that the international date line affords—remains astonishingly prevalent among professionals today.” [20] As she writes, in professions where total hours spent on the job are not “explicitly reward[ed]… the pressure to arrive early, stay late, and be available, always,” [21] even on weekends, can exert great pressure. Options that redefine the time and place of work—working from home and employing technologies for telecommuting—are available to all, changing how we manage work and personal time. Clearly, this is quite a serious concern for the cultures of both architectural education and the profession of architecture. If we teach students to value their time (the equal benefit of all classes, not just design studio) and to value the quality of their life, there would be a dramatic shift in the types of jobs students will seek in the profession at large.

In the fall of 2013, I tested a design studio work contract in the hope of changing studio culture and putting some of my ideas into practice. The negotiated contract, eventually agreed upon and signed by every student, created parameters that all students would follow. These included such things as a nightly departure time, implementation of a work ethic during studio class hours—foregoing emailing, video watching, or socializing—and the biggest one of all: pulling no all-nighters. Did this work? Overall, yes. We had sporadic check-ins and the students were honest when they fell short. Some of these rules were broken near project deadlines, but the contract did begin to influence and change their work patterns. Two former students mentioned to me in passing the following semester, that they are continuing to follow our contract. This demonstrates the potential of working with students to help them change their work habits and realize what better work–life balance feels like.

2. Redefining the arc of a successful career

I would add redefining what a ‘successful’ career even looks like for an architect. As Slaughter has written, “[t]he American definition of a successful professional is someone who can climb the ladder the furthest in the shortest time, generally peaking between ages 45 and 55. It is a definition well suited to the mid-20th century, an era when people had kids in their 20s, stayed in one job, retired at 67, and were dead, on average, by age 71.” [22]

One example she provides that resonates with architecture communities is the tenure track process. This example demonstrates how an institution can create policies that support all faculty.

[I]n 1970, Princeton established a tenure-extension policy that allowed female assistant professors expecting a child to request a one-year extension on their tenure clocks. This policy was later extended to men, and broadened to include adoptions. In the early 2000s, two reports…discovered that only about 3 percent of assistant professors requested tenure extensions in a given year…[a]nd women were much more likely than men to think that a tenure extension would be detrimental to an assistant professor’s career. [I]n 2005, under President Shirley Tilghman, Princeton changed the default rule…announc[ing]…all assistant professors, female and male, who had a new child would automatically receive a one-year extension…with no opt-outs allowed. Instead, assistant professors could request early consideration for tenure if they wished. The number of assistant professors who receive a tenure extension has tripled since th[is] change. [23]

3. Innovation nation

Slaughter mentions Deborah Epstein, the president of Flex-Time Lawyers, a national consulting company committed to increasing retention rates of female attorneys, and formerly a big-firm litigator. Epstein describes, in her book Law and Reorder:

… a legal profession “where the billable hour no longer works”; where attorneys, judges, recruiters, and academics all agree that this system of compensation has perverted the industry, leading to brutal work hours, massive inefficiency, and highly inflated costs. [Does this sound familiar?] The answer—already being deployed in different corners of the industry—is a combination of alternative fee structures, virtual firms, women-owned firms, and the outsourcing of discrete legal jobs to other jurisdictions. Women, and Generation X and Y lawyers more generally, are pushing for these changes on the supply side; clients determined to reduce legal fees and increase flexible service are pulling on the demand side. Slowly, change is happening. [24]

It is important to note that both law and medicine have been more successful in retaining and promoting women into their upper ranks. Clearly, this rethinking of law’s professional structure will make even more positive changes in the practice of Law. Architects must take note that change is happening in other historically male-dominated professions.

Slaughter concludes by writing “[i]f women are ever to achieve real equality as leaders, then we have to stop accepting male behavior and male choices as the default and the ideal. We must insist on changing social policies and bending career tracks to accommodate our choices, too. We’ll create a better society in the process.” [25]

Although there has been much warranted critique of Slaughter’s essay, including numerous articles, op-eds, blog posts, and TV and radio discussions, [26] I believe the national conversation is critical. People are now talking about these issues more broadly and are receiving much more exposure and airtime. However, I find the article does not accurately reflect the generations of us, both men and women, who are younger than she is. Although Slaughter acknowledged her position of privilege (including a tenured husband also teaching at Princeton), what is not being discussed is the critical point, that all those who fall outside of the elite world she is writing about, such as single people, [27] the working poor, and middle class families struggling to make ends meet, have very little power to demand such things as flex time from work, equal pay, or even paid sick leave. On the most basic level they would just like to remain employed. These are people that patronage and privilege excludes.

To a certain degree, Slaughter’s article tries to challenge, albeit unsuccessfully, reliance on simplistic stereotypes based on gendered social definitions, such as ‘women nurture more,’ ‘women choose family over career more often,’ ‘men are socialized to be the breadwinner while women are socialized to be the caregiver.’ [28]These are just beyond passé. As philosopher Linda Hirshman writes in regards to Slaughter’s article, “[these stereotypes are] destructive because she legitimates a lot of behaviors and attitudes that make the gender claim a self-fulfilling prophecy…. But most destructive of all is that the problem she’s identified—the staggering speedup of jobs at the top—is not a woman’s problem. It’s the predictable and unavoidable result of the increasing inequality of the American economy. The chasm between the 1 percent and the rest is so deep and so life-defining that people will do anything to stay in the 1 percent.” [29]

Another issue that Slaughter’s article provoked me to consider is the general acceptance of architecture’s professional structure, a structure that our students are socialized into accepting from beginning design studios, onwards. Rare is it to hear about either an academic setting or a design firm that calls out for radical rethinking of how work works. A few examples that call into question these structures are highlighted below.

At Transform in May, 2013, in Melbourne, Australia, an event hosted by Parlour, an Australian women’s architecture group invested in women, equity, and architecture, one session asked, “Do architectural workplace cultures need to change?” [30] I was so encouraged to find an array of small to large firms speaking about their different approaches to how time is structured and managed. For example, Dunn & Hillam Architects, the Sydney-based award-winning design firm, spoke about how all employees, including the partners, only work part time.

In conversations since the event, Lee Dunn confided to me that even before her architectural education—during primary school that included students from 5 to 12 year olds in the same classroom—her teacher would give to the different age levels their work to accomplish for the week. It was up to each student to figure out when to do her work: you could finish all your work early in the week and then have the rest of the time to play, or do some work every day. This clearly influenced her experience and, while an architecture student, she thought it just did not make sense to work all the time. The lessons of these educational experiences were further reinforced while working for Richard LePlastrier, prior to opening her office. She discussed with me how this work experience influenced how she and her partner created their own life-work structure. LePlasterier lives a nuanced balance of how work fits into his life, and demonstrates how an organized life with no strict hours for work can produce excellent design.

Dunn & Hillam have structured their firm to encourage their employees to have lives outside of the office. Because everyone works part time, there is a great need for flexibility from both employers and employees. If work is slow they let people know so if opportunities arise, their staff can teach or take on a side job, for example. They also ask other firms to temporarily hire some of their staff during slow times. However, when there is a lot of work, they still manage to work part time. In fact, they have a kill switch for the power, and if people are working past 6 p.m., they threaten to use it. They are insistent that people do not work late. She believes part of their success is being able to effectively manage workflow, and not overload their employees.

Financially, they pay their staff for every hour they work, so they do make less profit than other firms. They are completely open with their staff about their business practices, and all four employees are knowingly paid the same amount. More broadly, they believe architecture is not about sitting behind a screen all day long, but living out in the world. For, how else are you supposed to design for life if you yourself do not have one? [31]

Mattapan Mobile Farm Stand;Studio Luz and BR+A+CE. Images © John Horner

Beyond Patronage participant Hansy Better Barraza, with Studio Luz and BR+A+CE, works to socially reform and entrepreneurially innovate our discipline in ways that specifically engage constituencies historically ignored. Through crowd-sourcing websites and micro-grants, raising their own money to enable projects such as the Mattapan Mobile Farm Stand and the Big Hammock, Barraza and her partners are proving that small-scale micro-infrastructural public installations can work to slowly subvert and overturn the layers of patronage in architecture. No longer financially reliant upon a person or company to actualize these small-scale projects, this process democratizes architecture and can provide more opportunities for communities to become involved in shaping their built environment.

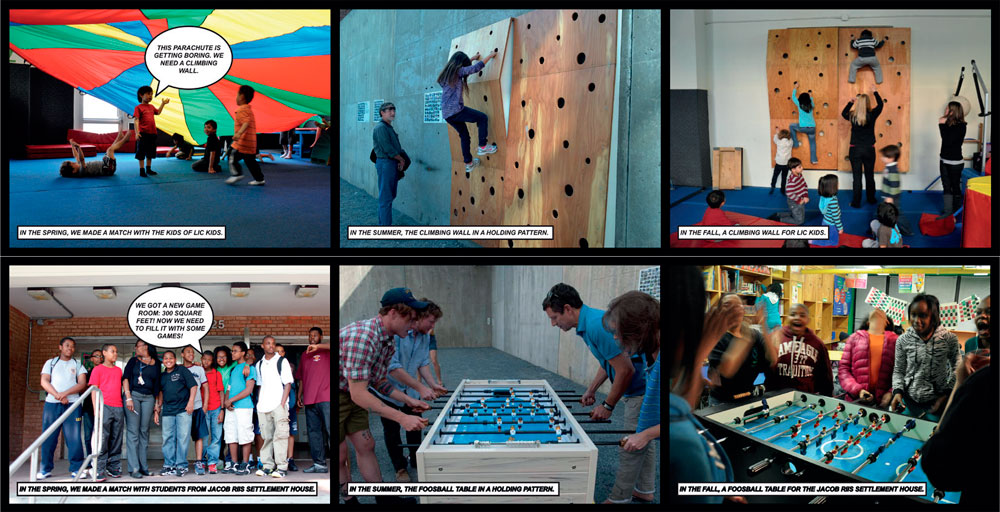

Holding Pattern for MOMA PS1, Interboro Partners: Jacob Riis neighborhood settlement and their new foosball table, Kids of LIC Kids and their new rock climbing wall.

Another example challenging how, for whom, and what gets architecturally produced is by Georgeen Theodore, with Interboro Partner’s Holding Pattern for MoMA PS1. The firm’s rethinking of the architect–client relationship and the products that result from it moves beyond fixation on the ‘precious object’ to relationships in which utility and adaptability are essential in engaging contemporary conditions. The fact that the project has more than 50 afterlives demonstrates how architectural strategy can impact a far greater cohort of people and varied demographics. Radically repositioning the architect as community advocate and community planner, and expanding that role to consider PS1’s neighbors, is a clear way to educate the public about the value of design while simultaneously improving the lives of those in the neighborhood. [32]

Patronage + Architecture

So, where does this leave us, thinking about the role of patronage and moving beyond patronage – looking at other ways to ‘do architecture’? I believe Hirshman’s connection to the 1% is quite important because patronage typically perpetuates and guards against any change—especially economic and social relations in which alternatives may be problematic for those administering patronage, as well as for those benefitting from it. This is an area I have been interested in and committed to for many years in order to advance and evolve our profession. This interest led to a travelling exhibition and subsequent book, Feminist Practices: Interdisciplinary Approaches to Women in Architecture, focusing on various forms of architectural investigations that employ a range of feminist methods of design research and practice by women designers, architects, and architectural historians. Two primary goals of the project are: to raise awareness for those both within and outside of the profession about the influences, diversities, and impacts of the feminist design practices happening now, and to expand how architecture is being defined today. [33]

I must dispel the belief that feminism is only about women—or for that matter that moving beyond patronage is strictly a woman’s concern. Although the feminist movement began with a vested interest in women’s rights and equality, that movement has expanded far beyond to encompass broader issues of social justice and equality for all under-privileged and under-represented people. In Feminist Practices, I define feminism by two particular positions. First, “as both feminist geographers Heidi Gottfried and Pamela Moss argue, feminist practices are political acts that seek to challenge the status quo and identified relationships of power. One of the many potentials these geographers see in using a feminist methodology is that of ‘an open and dynamic knowledge community.’”[34] The second position is that, “there are those who work to improve and better the lives and spaces of others, concerned with larger social justice efforts, but may never call themselves feminist. As feminist activist bell hooks writes, there are those who “may practice theorizing without ever knowing/possessing the term, just as we can live and act in feminist resistance without ever using the word ‘feminism.’”[35]I seek a feminism that encompasses a wide array of social justice issues in order to create a more equitable world for all.

I am interested in how one can more broadly define architecture, and what relationships can be made between feminist methodologies and their various approaches to design. “If feminism,” as hooks posits, “defined in such a way call[ing] attention to the diversity of women’s social and political reality, …compelled [us] to examine systems of domination and our role in their maintenance and perpetuation,”[36] then we as designers must begin by questioning normative design relations and their expected outcomes, [37] such as systems of patronage that exclude us.

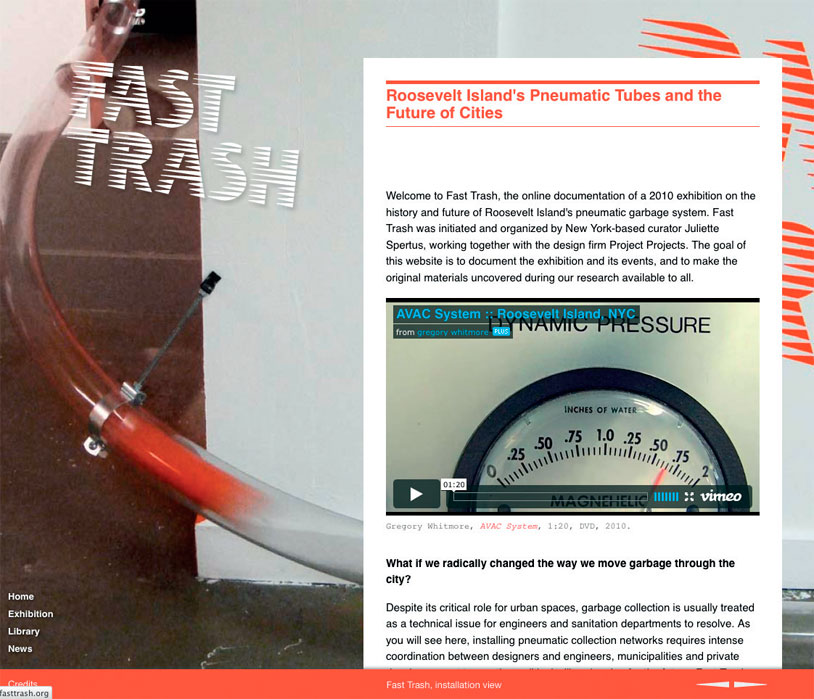

Fast Trash Website, Juliette Spertus with Project Projects

Another project presented in the symposium, by Juliette Spertus, “From Fast Trash to NYC Tubes,” demonstrates how Spertus and her collaborative team seeks alternative approaches for waste management in New York. Beginning with an exhibit in a community-run art space that she describes as “part infrastructure portrait, part urban history, and part site-specific installation,” her project creatively engages various approaches to bring information to the public, from walking tours, a symposium, and an online exhibit, to a video about invisible garbage. The use of cultural programming as a way to educate the public about the serious issues of garbage enabled not only greater public awareness around waste but also the engagement of city officials. This was a smart approach. It demonstrates imaginative possibilities for a way to move beyond patronage and raise awareness of the value of design.

If not patronage, then what?

I led a series of roundtable discussions at the Van Alen Bookstore in New York, in March, 2012, with various female architectural practitioners and academics discussing some of the themes of my book. It became clear that there is still a great need for support and mentoring for women and minorities in our profession. Many people who attended spoke out about many of their concerns. I began an ongoing conversation about these issues with a person I met at the last Van Alan event, Nina Freedman, Director of Projects for Shigeru Ban. We began to strategize about ways to build upon the momentum and energy of the events, and the need to start something that would address what we had been feeling as a real crisis in the profession. In September, 2012, we launched a group for women in New York, with about 30 people attending—creating networking and mentoring across a wide age range of women. We successfully completed an online fundraising campaign to create ArchiteXX with our online presence and ongoing programming efforts. [38]

Clearly, all these concerns are not new. Is it déjà vu? Is it a rehashing of the 1970s? I would argue no, but a building upon those who have come before us. An important article, published in September, 2012, in The Design Observer Places, by Gabrielle Esperdy, “The Incredible True Adventures of the Architectress in America,” speaks to this, where she provides an historical analysis of the 1970s, when women were, as she writes, “redefining architecture itself; women were bringing feminist voices to existing systems and institutions and challenging the architectural establishment; women were forming new feminist alliances and addressing their own professional needs.” [39] The term “architectress,” re-coined by Joseph Hudnut, a former dean of Harvard’s Graduate School of Design, was the title of a two-part article that he wrote in 1951 in support of women in the profession of architecture. [40]

As the Beyond Patronage symposium confronted the idea of moving beyond patronage, it inadvertently and cleverly challenged the long legacy of struggle for change within our still-very-male profession. This built upon a history of others who enabled all of us to be here today. As Esperdy’s article questions:

[Is] sexism in the architecture profession in the middle of the last century rendered safe for consumption at the beginning of this century… now that women have designed important buildings, won Pritzkers, made partner, become deans, gotten tenure and, in the United States, represent approximately 20 percent of practicing architects[?] No one would question women’s considerable advances in the six decades since “The Architectress.” But those advances didn’t happen overnight and they didn’t happen without effort, organizing and activism. [41]

But from where I sit, there are still many critical issues needing far greater movement, for ongoing and significant change to occur.

Whether or not the f-word, dare I say, ‘feminism’ in architecture is one embraced by many any longer, there is clearly a resurgence of its need. To think of different and even more radical approaches to practice, moving beyond patronage requires that all possibilities be on the table for consideration. I have noticed in my 13 years of teaching that there is a real distancing from feminist associations by students and even some faculty. But it was interesting to note that, although younger students and recent graduates may not self-identify as feminist, they turned out to the Van Alen events in search of something that is integral to feminist principles and social justice movements working for greater diversity and inclusion. [42] As one younger woman commented in the last roundtable discussion, “People are looking for this [referring to the discussion of the state of the profession]. These conversations are not happening in the schools. People are freaking out.” [43] Another woman, who mentioned that she was a sole practitioner, said that there is no real support and exchange of work and opportunities. She is finding the profession to be a very isolating environment. If you are trying to juggle everything, you are very alone, regardless of gender. [44]

It is only obvious to connect the Beyond Patronage symposium with the Peter Reyner Banham Fellowship at the University at Buffalo. As the fellowship website mentions, “[t]he Banham Fellowship in Architecture is intended to support design work that situates architecture within the general field of socio-cultural and material critique.” [45] Banham’s essay, “A Black Box,” criticizes architecture for its entrenchment within itself and the solipsism that the discipline instills and perpetuates from the very beginning of architectural education, especially within design studio pedagogy and culture. The discipline, as he argues, operates on a very narrow value system with “unspoken—or unspeakable—assumptions on which it rests.” Architecture, no longer acknowledged as the “dominant mode of rational design,” is seen as the “exercise of an arcane and privileged aesthetic code.” He goes even further, lambasting architecture as too proud and too accepting of a “parochial rule book [that] can only seem a crippling limitation on building’s power to serve humanity.” However, he ends the essay with a glimmer of hope, that if architecture would allow itself to be “opened up to the understandings of the profane and the vulgar, at the risk of destroying itself as an art in the process,” [46] then architecture may find an active and engaged existence in the world. [47]

It is precisely this existence and participation in the profession that Beyond Patronage seeks. It is a practice where, to quote the editors of Architecture and Participation, “participation is not always regarded as the guarantee of sustainability within a project, but as an approach that assumes risks and uncertainty.” [48] These uncertainties and places of potential conflict “forc[e] it to engage with issues that in the long term will make architecture more responsive and responsible.” This results in an “alternative means of production … [that] leads to alternative aesthetics and spatialities.” Moving beyond patronage suggests an “expanded field for architectural practice; it is a means of reinvigorating architecture, bringing benefit to users and architects alike.” [49]

Conclusion

Returning to Linda Hirschman’s earlier critique, I would like to borrow and extend her argument connecting to the issues that the symposium raises around patronage and privilege. They are actually about the 1% and the ways our entrenched systems of practice and teaching, including pedagogy and curriculum, perpetuate and even promote inequalities. This space beyond patronage is where agency and true empowerment is located. The symposium and this book are evidence of just such possibilities. Every participant, in various ways through her own practice, demonstrates what beyond patronage looks like.

Environmental Health Clinic © Natalie Jeremijenko

For example, Natalie Jeremijenko, designer, artist, innovator, and inventor, among other titles, seeks to capitalize on new technologies for social change. Through public experimentation, folly and science, and relying upon participatory research, “she is interested in the production of knowledge, and information, and the political and social possibilities (and limitations) of information and emerging technologies.” [50] One of her projects, the Environmental Health Clinic, requires the public to be engaged and work to change environmental health issues that one is concerned with. Rather than passively waiting for a doctor to diagnose and prescribe, the ‘patient’s’ prescription is to go out and take action! As Jeremijenko states, “I try to underscore the fact that we are complicit and responsible for our technology, to dispel the notion that it is a foreign object…We’re not being passively impacted by these technologies. Rather, we are actively designing them, and we can use sociotechnical analyses in generating new designs.” [51]

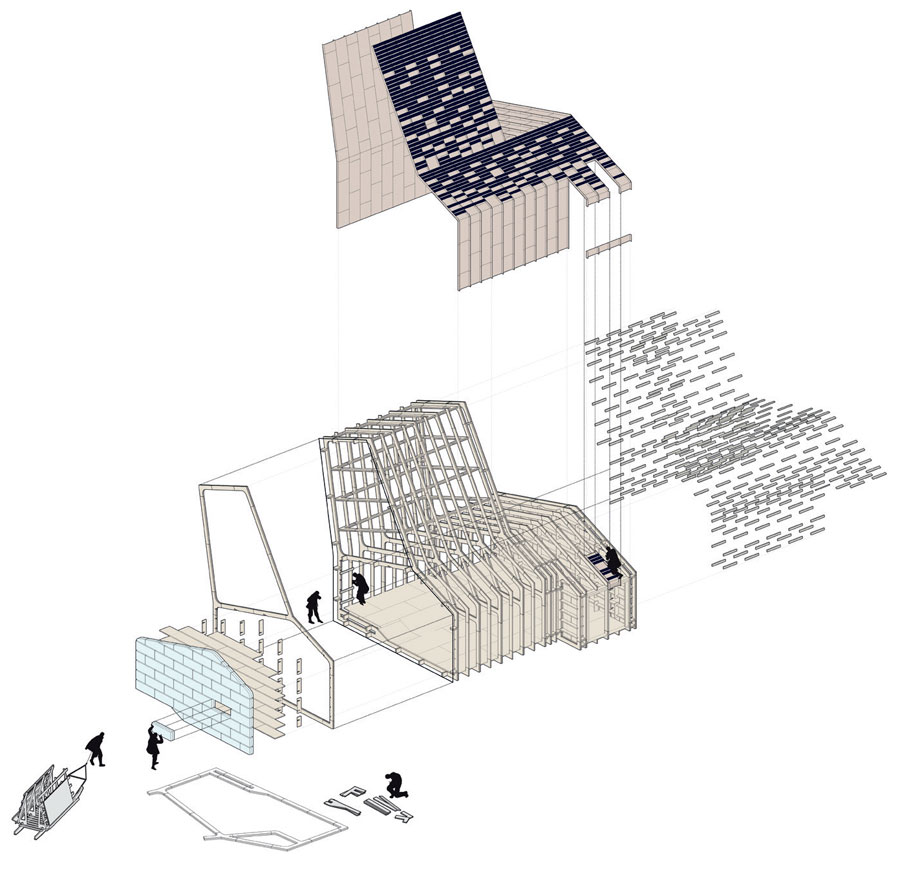

Arctic Food Network © Lateral Office: The project looks to hybridize traditional building customs (sled construction) and contemporary building techniques (CNC milled joints) to build local capacity and address the challenges of construction in the North.

Lola Sheppard and Lateral Office seek possibilities beyond the normative idea of site by engaging environmental data, economic forces, and ecologies as elements to be researched and mined for their spatial agency. Within the conceptual framing of Arctic Food Network, the project proposes a new system for northern Canadian populations to access and further develop local food traditions and as possible sources of revenue streams for themselves. Design in this project is not as concerned with creating spaces for inhabitation, which it does, but also, more importantly, with creating knowledge exchange and education, social connection, and cultural and historical reclamation. As design takes on these significant issues it moves beyond preoccupation with form to issues that are integral to the sustainability of civilization.

This is the future of architecture and, using the symposium organizers’ own words, “is central and critical to the survival of our profession.”[52]

Another important area to consider in moving beyond patronage is holding architectural practices more accountable to fair and inclusive work policies. At the last Van Alen roundtable, Yale University architecture professor Peggy Deamer mentioned that, one day when she was walking through the Yale Law School, she noticed the “Top Ten Family Friendly Law Firms” advertised for upcoming graduates. Her immediate response was that you would never see this in architecture schools. She was shocked by her own response, asking “What is the difference, why not in architecture?” Digging a bit deeper on the Yale Law Women’s website, I realized this is a student organization that has been putting pressure on law firms to change for over 8 years. Yale Law Women are interested in firms that are deconstructing gender stereotypes of “bread-winner” and “care-giver” by creating “family friendly options to attorneys of both genders on equal terms.” They highlight part-time/flex-time and family care policies as well as leadership and promotion rates as a way to promote those firms who have fairer practices. Quoting from their site: “Yale Law Women produces its annual Top Ten Family Firms report to raise awareness of gender disparities within the legal profession as well as to highlight progress and innovative solutions. We believe that the legal industry is capable of making major strides to improve the experiences of women and men attorneys alike. That improvement hinges on careful attention to utilization in addition to availability of family-friendly policies.”[53] Students are such a critical piece in moving beyond patronage. As English Professor Gayle Greene writes in “Putting Principle into Practice”:

How can we use our educational apparatuses and institutions to make social change—how we can reinvigorate “our capacity as agents to act as well as to know otherwise, to intervene in the world as well as the academy, to have an effect.”[54]

Yale Law Women are doing just that.

As educators, we all have a responsibility to question and think beyond the models we were educated under. Architecture is always one of the last professions to embrace current intellectual movements, be those theoretical, technological, or sustainable. It remains far behind in diversifying our ranks. According to the 2011 National Architectural Accrediting Board report:

79% of full professors are men and 85% are white

73% of associate professors are men and 79% are white

68% of assistant professors are men and 72% are white

70% of instructors are men and 75% are white [55]

Architectural curricula still embody the legacies of “dead white men” and communicate that the “best” architects you should emulate “are white and male.” [56] Furthermore, a school’s public events roster is also quite telling. Those who are invited speakers for lectures and symposia remain predominately male, with students having far fewer opportunities to be exposed to female architects and designers. [57] For the fall and spring semesters of the 2012-2013 academic year, my research assistants found that, of the 73 schools where information was easily accessed, almost 62% had between either no women or only one woman invited as a public lecturer. Additionally, over 1/3 or 34.3% of these schools had no women as part of their public programming at all. This is a disturbing statistic. As Stratigakos [58] has noted:

Jeremy Till, head of the London art and design college Central Saint Martin’s, has pledged to refuse to participate in lecture series with less than 30 percent female representation. His position, he writes, “is more than just a numbers game. It is often said that knowledge is power. These male-dominated platforms are the means for the perpetuation of male models of knowledge, and with them the perpetuation of male systems of power…. I am increasingly intemperate of male-dominated discourse and the values it represents: the architect as thrusting hero, the endless ‘show and tells’ with the architect at the centre, the clubbiness of the whole scene with women excluded from those all important informal networks.

As demonstrated by the Yale Law Women, students can also put pressure on schools and the discipline at large to force change. What would happen if architecture students across North America began to put pressure and demand more diverse lecture series? Or more diverse faculties?

Beyond patronage = radical rethinking

Where I find such great potential in moving beyond patronage is how these strategies are creating new ways of defining what architectural practice is. I believe agency comes from the desire, the actual necessity to figure out how we can stake our claim within a still very homogeneous profession. Beyond Patronage reconfigures and rethinks both academia and practice.

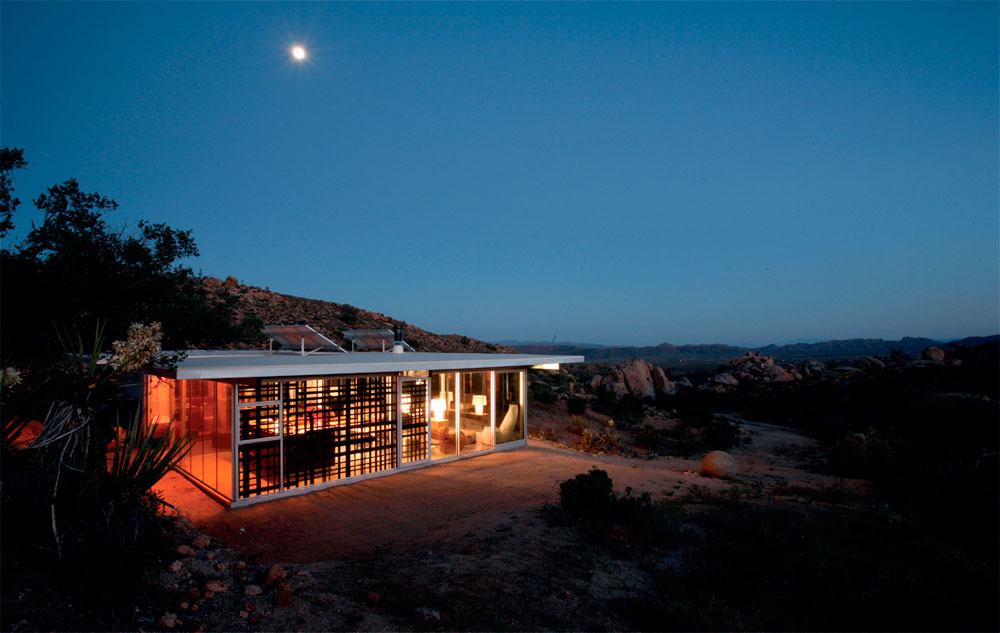

IT House, Taalman Koch

Another participant from the symposium included Linda Taalman. Her interest in challenging the iconic idea of “architect as sole creator” has shaped her entire career thus far. Willing to relinquish some aspects of design control and venture into the unknown, she and her collaborators have sought different ways to work and fully participate in the process of design. This takes real courage and confidence where one is willing, as Banham suggests, to allow one’s work to be “opened up to the understandings of the profane and the vulgar, at the risk of destroying itself as an art in the process.” [59] The IT House system and its ongoing development exemplify this potential. By designing adaptable systems, both spatially and environmentally, this project is able to engage a much wider audience with ongoing iterations, both domestically and commercially. It is also interesting to note that the use of social media has greatly expanded future client potentials and communication strategies with ‘fans’ and clients alike.

Silent Witness: Remnants of Slave Spaces Casa dos Contos Corner Projections, Ouro Preto, Brazil, Yolande Daniels.

On line at the center of the radial paving stones, adjacent to the courtyard where the whipping post was located, as one passes through the great hall, a small stair is sighted.

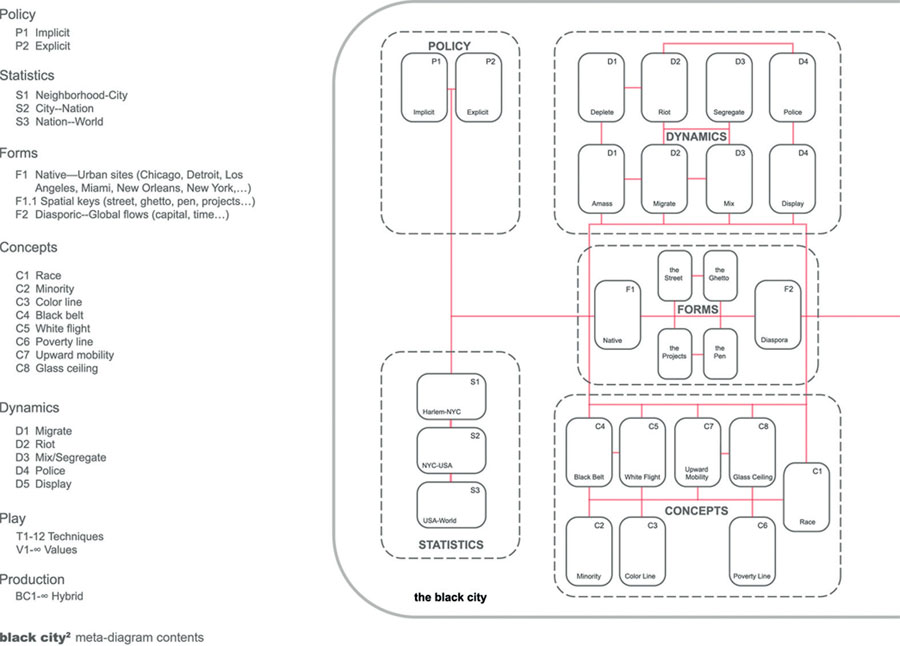

Yolande Daniels’ projects presented at the symposium investigate and critique complex social and political issues, specifically those pertaining to race. Seeking to both reveal and speculate upon this often-sidelined area in architecture, her work presents new possibilities for the role of design thinking. Through mapping space’s invisible structures, be those of history, text, census data, or policy, she mines this data for new potentials and futures of such spaces.

black city2, Yolande Daniels

All of the projects included in this anthology and that were presented at the symposium confront real social and economic problems overlooked by our government and social structures, and provide creative design solutions to improve community members’ lives in the process. In their own ways, each envisions and practices a different way to ‘think and practice’ architecture. Part grassroots and part community activists, if we architects and designers are going to change the world, I argue it is from the ground up that it is going to happen. We can no longer, as Better Barraza argued at the symposium, play the ‘waiting for opportunities’ game, but are now required to be architect, entrepreneur, and community activist. Moving beyond mere form-maker, we must recognize and acknowledge the complexities inherent in our world—be those economic, social, political, environmental—and capitalize on their potential as agents of change.

We must enable more women and people of color into our ranks, at all levels. We must create successful networking and mentoring programs. Yes, it is important to discover ways to change from within these structures, but I also think we must be far more radical in ways to work outside of them—moving beyond patronage, privilege, and the 1%. We have to begin to take this on because the future of our profession, and design in general depends on us doing so.