‘Utrecht is the fastest growing city in the Netherlands, on the way to over 400,000 inhabitants. That growth is mainly concentrated in the west. With the development of the Leidsche Rijn housing area, comparable in size to the city of Leeuwarden, the geographical centre of Utrecht lies in the quarter of Oog in Al. That creates very different dynamics. The station, which was always situated on the edge of downtown, is now in the middle of an enlarged centre.’ Says alderman Victor Everhardt, responsible for the redevelopment of the Station Area since 2010. ‘The discussion about the redevelopment began in the seventies, not long after the huge shopping and office development of Hoog Catharijne was completed. Different plans appeared, which nonetheless never led to decisions. Therefore, there was constant political attention. A political party like Leefbaar Utrecht (Livable Utrecht) gained great success because of that.’ It took until 2002 for a breakthrough. In a referendum, the people of Utrecht chose between two future visions. The winning model was developed into the Station Area Master Plan, which has since been the basis for a radical transformation of the area. According to Everhardt: ‘The task is much broader than the renovation of the station and its immediate surroundings. It deals with a large area, from the historic city centre town to the Jaarbeurs (fair complex) on the west side. There are numerous parties involved, including Klépierre (owner of Hoog Catharijne), the Jaarbeurs and NS Dutch Railway Company. As the municipality, we took responsibility for a number of projects, like Tivoli Vredenburg and the new City Hall, which we also own.’

One of the objectives of CU2030, as the plan for the Station Area is now called, is to incorporate the area west of the station as part of the centre. Everhardt says: ‘We are literally enlarging the centre of Utrecht. West of the tracks, we are creating a downtown area that is supplemental to the historic downtown with its specific quality. Because the Jaarbeurs only needs half of its area in the future, four hectares will become available for living, working and leisure; it is therefore not an expansion of the shopping area. With features like the Beatrix Theater and a new large cinema complex, it will become an area which is lively 24/7. A large square and broad stair will soon also give the station a face on the west side. It will become an open-air stage, where even festivals or other activities can take place.’ Another part of the transformation is to create better permeability for the area. Everhardt comments: ‘In Utrecht, the tracks have always been a physical barrier between east and west. From the station to Bleekstraat, a distance of 1.6 kilometers, there was not a single cross-connection. The new bridge solves this problem. This creates a route for cyclists and pedestrians between the Mariaplaats, in the historic center, and the offices and residential areas west of the tracks, like the Croeselaan and Dichterswijk. It is also an alternative route via the Westplein and Vredenburg, one of the busiest cycle paths in the Netherlands.’

One of the objectives of CU2030, as the plan for the Station Area is now called, is to incorporate the area west of the station as part of the centre. Everhardt says: ‘We are literally enlarging the centre of Utrecht. West of the tracks, we are creating a downtown area that is supplemental to the historic downtown with its specific quality. Because the Jaarbeurs only needs half of its area in the future, four hectares will become available for living, working and leisure; it is therefore not an expansion of the shopping area. With features like the Beatrix Theater and a new large cinema complex, it will become an area which is lively 24/7. A large square and broad stair will soon also give the station a face on the west side. It will become an open-air stage, where even festivals or other activities can take place.’ Another part of the transformation is to create better permeability for the area. Everhardt comments: ‘In Utrecht, the tracks have always been a physical barrier between east and west. From the station to Bleekstraat, a distance of 1.6 kilometers, there was not a single cross-connection. The new bridge solves this problem. This creates a route for cyclists and pedestrians between the Mariaplaats, in the historic center, and the offices and residential areas west of the tracks, like the Croeselaan and Dichterswijk. It is also an alternative route via the Westplein and Vredenburg, one of the busiest cycle paths in the Netherlands.’

The initiative of the new connection has been warmly supported by the Rabo bank; the bridge runs right past the head office. In the negotiations regarding the new office tower, the Rabo bank therefore agreed to a major financial remittance linked to the ‘Rabo Bridge’, as the Moreelse Bridge was initially known. In return, the Rabo bank head office was directly connected to the bridge.

Residents and businesses in the area responded positively to the construction of the Moreelse Bridge. Everhardt notes: ‘They really wanted the new connection. Obviously building entails some inconvenience, but we have tried to minimize it. In the immediate vicinity we had to deal mainly with offices and people who live above Hoog Catharijne itself. We communicated very actively, and residents and partners were constantly involved. That is something we have had a lot of experience with in over recent years.’

The Moreelse Bridge doesn’t offer any access to the platforms. However, the facilities are in place to build stairs at a later time. Everhardt explains why the stairs are not there yet, ‘After the referendum, the contracts with various parties were closed, including Klépierre (then Corio), the owner of Hoog Catharijne. Klépierre was an important party involved in the regeneration of the area and they wanted to invest strongly, but there were concerns about the loss of the direct connection between Hoog Catharijne and the station (Public Transport Terminal). Therefore, it was agreed that the number of pedestrian routes to and from the Public Transport Terminal on the east side would be limited. The area is still fully under construction, including the building of the east station square and renovation of Hoog Catharijne. When everything is ready, we will reassess the pedestrian flows. Surely then there will be another moment when we will discuss how the whole complex functions, and whether it is necessary, from a safety perspective for example, to add the stairs.’ Cyclists using the Moreelse Bridge have to dismount at the beginning and the end and use the ‘bicycle gutter’ along the stairs (or the elevator) to go up and down. There simply wasn’t enough space for a ramp that would be accessible by bike. Everhardt is not afraid that cyclists will avoid the bridge for that reason. ‘For a large part of the city, the new connection means that you no longer need to make a large detour. Those people really benefit. For others, it is a quiet alternative to the busy route over the Vredenburg. I have full confidence in that.’

The Idea

‘The municipality asked for an iconic bridge,’ says Ronald Schleurholts, architect and director of cepezed. ‘Spectacular bridges like the ones Santiago Calatrava designs jump to mind immediately: a cable stayed bridge that spans the whole distance at once. But such a bridge would not only be massively expensive, it would have been difficult to build in such a complex location.’ In addition, a long span would not be very logical. After all, on each platform you can make a buttress. ‘That’s why we didn’t propose an icon in the form of a grand gesture, but rather a friendly tree-lined avenue which is part of the city and passes over three hundred meters of infrastructure.’

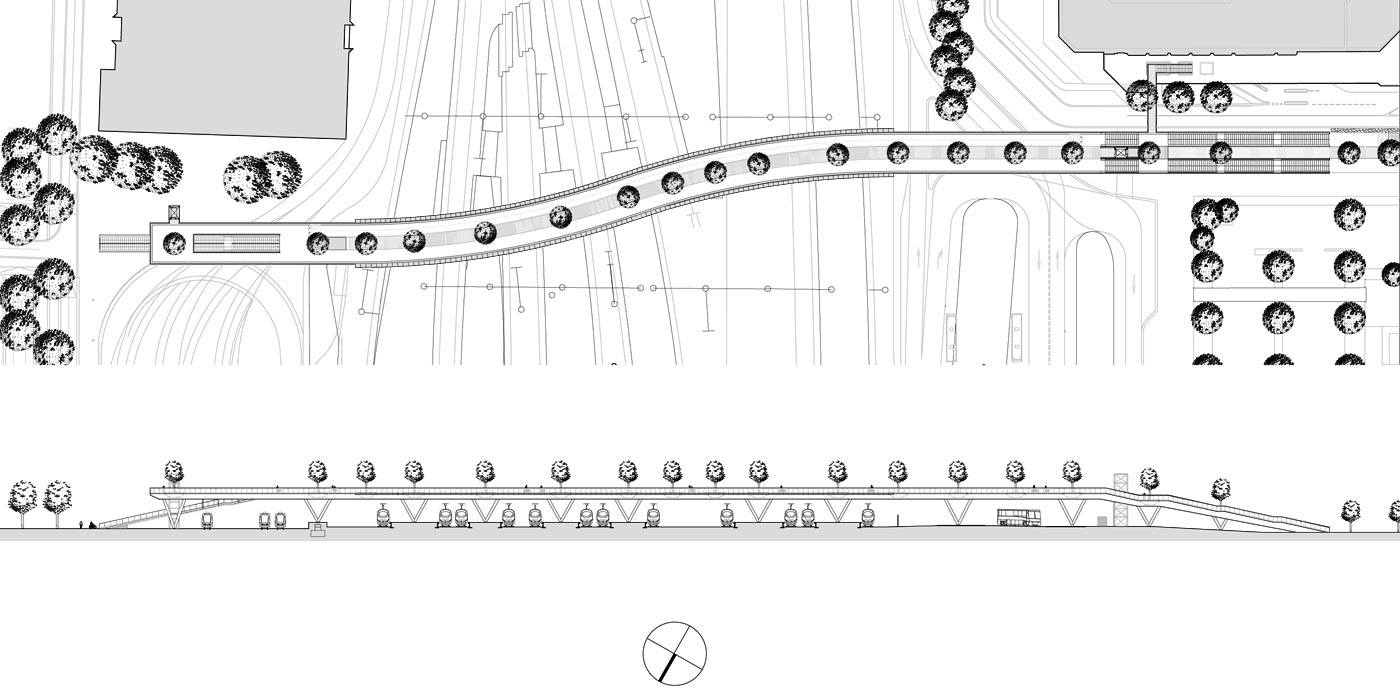

Site Plan

Because the bridge connects streets on both sides that do not lie directly opposite each other, we gave it a double curve resulting in an even friendlier character, According to Schleurholts: ‘At a certain point you can see over to the side of the bridge. One moment you look straight towards the trees, the next moment you look past them. That wavy motion makes it feel almost like a park route for cyclists and walkers.’

Plan & Elevation

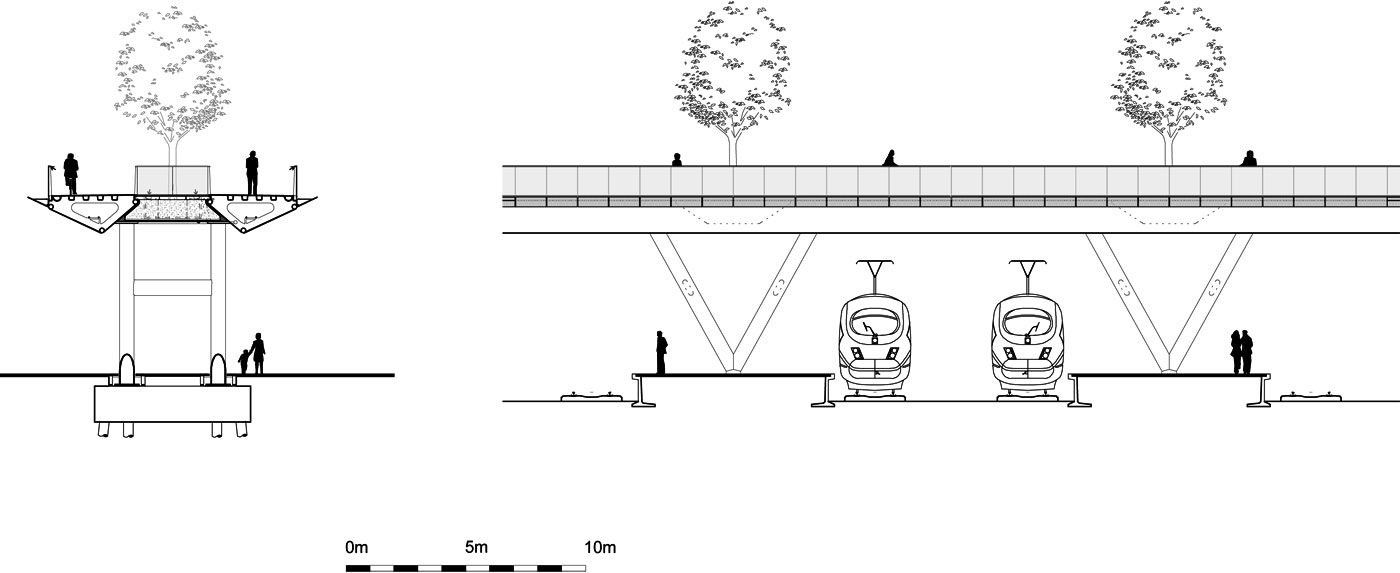

Section & Elevation Detail

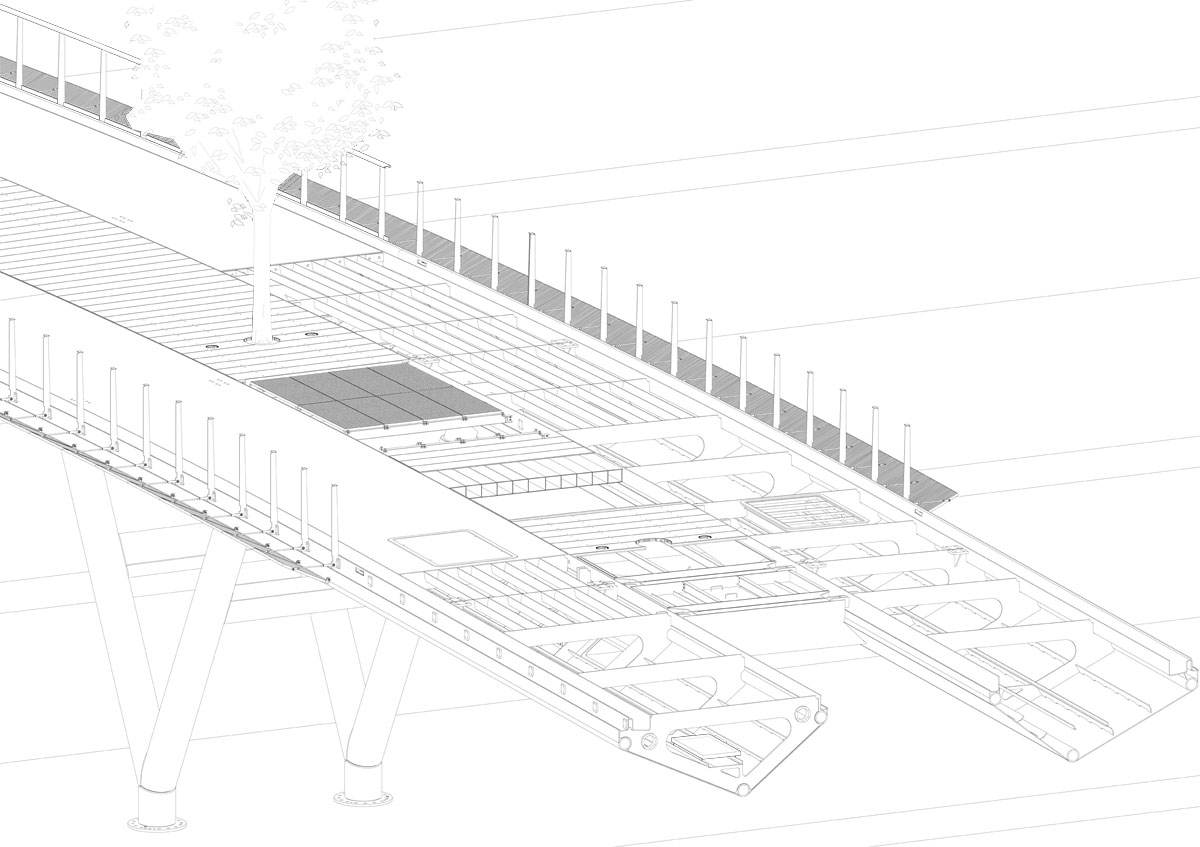

Drawings

It’s the trees that make the bridge recognizable. Schleurholts says: ‘For the rest, it was a matter of making a carefully designed bridge with a very slim profile, tapered bridge elements and a glass railing with integrated LED lighting. For us, it was crucial that, apart from the trees, no other vertical elements were on the bridge. So no lampposts, security cameras on poles or signs. In this way, we wanted to emphasize the effect of vertical trees in an otherwise horizontal context. In the evening, this is emphasized by illuminating the trees from below.’ On the side of the Moreelsepark the trees extend to the head of the bridge, while on the Jaarbeurs side, where the bridge gradually slopes down, the trees continue on street level up to the Croeselaan. cepezed, in collaboration with the ProRail-approved engineers ABT and Arup, obtained the design contract following a European tender procedure. The combination won with a proposal which focused on the bridge’s design. Their proposal anticipated the construction above a rail yard that is almost permanently in use. They knew that a significant part of the work could only be carried out during two weekends that had already been planned well ahead of time, when the rail-traffic would be completely shut down for a recast of the tracks. Schleurholts says: ‘To make sure the bridge could be built within the limited timeframe of that ‘train-free period’, we proposed a kind of kit based on large prefabricated parts, which could be assembled in a short time.’ The kit included two main elements: support points in the form of a double-V, and bridge parts that connected the support points over the tracks. Because of the V shape, the columns take up relatively little space on the platforms, and on top the distances between the support points are shorter. As a result, shorter spans were needed. Initially the idea was for support to use one V-shaped column. The projected stairs to the platforms would provide additional stability. But since these stairs will not be executed for the time being, ultimately we settled on a construction using two paired V-shaped columns. In this way, the stability is also guaranteed without stairs. Measures were taken to allow for building the steps at a later date; this explains the openings in the deck that are now filled with steel grating. For the bridge sections, one of the main issues was to make them as slender as possible. Schleurholts says: ‘We wanted a user-friendly bridge. With a slim bridge, cyclists and pedestrians do not have to cover a large height. To get that done, we designed the bridge on the razor’s edge.’ In addition, ABT had an important role.

André Speksnijder, senior adviser of construction at ABT comments: ‘Because of the slenderness of the deck and the V-shaped support structure, we were faced with a special challenge: pedestrians and joggers might cause unpleasant movements in the bridge. In order to prevent vibrations, we included shock-absorbers in the structure.’

Other amenities which contribute to the comfort are the ‘walk-through elevators’ (which you can exit on the opposite side with your bike and which are also accessible for maintenance vehicles and ambulance motorbikes) and carefully positioned ‘bike gutters’ on either side of the stairs. Escalators and ‘tapis roulants’ (moving walkways) were considered, but they proved susceptible to interference; moreover an escalator is rather unhandy for cyclists.

It was the municipality of Utrecht that initiated the project. Until the building permit, it acted as principal. Because the bridge crosses the railway, that role was subsequently taken over by ProRail. The municipality and ProRail agreed that cepezed and ABT would need to remain closely involved in the ongoing elaboration.

So the two offices kept a hold on the design. Schleurholts says: ‘Ideally, we design each screw ourselves. In this case it came down to the fact that we worked out the design of the visible part of the bridge.’ For the non-visible parts of the structure the steel contractor BSB was given ample freedom to develop the design further. A good example is the trough-shaped main beams, the supports of the bridge deck.

Their appearance was recorded in the draft by cepezed. Subsequently it was the steel contractor BSB who invented a supporting structure with round tubes in the three corners. On the outside, this produced a tight steel skin which emphasizes the architecture of the bridge.

Speksnijder points out: ‘During the preliminary phase we calculated the constructive feasibility and determined whether the bridge would keep to the budget. By clearly defining the appearance together with cepezed, we created boundaries in which there is enough freedom for a contractor to come up with its own solutions.’

ABT was later given further role. Speksnijder: ‘We started as a construction consultant via cepezed. Then for ProRail we also drew up the contract and supported the procurement. After a contractor was selected, we played a supporting and monitoring role in the implementation for ProRail, while cepezed monitored the quality for the City of Utrecht.’