Cultural Events, Competitions and Public Debate as Impetus for Architectural Culture in Flanders, 1974-2000.

1974. Belgium was in the midst of an architectural crisis. Between 1965 and 1975, according to Geert Bekaert, architecture was slowly going under. [1] Due to the economic malaise the building industry went into serious decline after 1973, and in particular young architects found it difficult to find work. Francis Strauven diagnosed the situation in 1980: ‘Once Belgian architecture had, and not without difficulty, assimilated functionalism or some derivative of it, and learned to concentrate on the production of ‘functionally’ expressive objects, it lost all sense of urban character and contextually, and now finds it extremely difficult to recapture those qualities’. [2] The malaise was caused by a mix of an ineffective or non-existent architectural policy, a politicized process of commissioning, inadequate conservation of historic buildings (with only few protected monuments) and architectural education that generally was not very inspiring and that gave short shrift to the discipline’s social responsibilities. Moreover, architects could not rely on a vivid architectural culture in Belgium. [3] There were no exhibition spaces in which architecture could be shown, nor places where it could be discussed from a cultural perspective. Brussels has two architectural archival institutes since 1968 (Sint-Lukas Archives and Archives d’Architecture Moderne), but they were more concerned with the loss of Brussels’ valuable heritage of art nouveau and art deco than with contemporary architecture. There were no competitions, the workings of the Association of Architects was heavily criticized and there was no critical magazine for architecture, despite the foundation of A+ in 1973. The lack of a forum for critique and the deteriorating Belgian construction climate was made painfully evident in a polemic by Geert Bekaert which, though refused by A+, was published in a special edition on Belgium in the Dutch magazine Wonen TA/BK in 1983. [4] One of the consequences was that there was no such thing as Belgian architecture abroad. Another was that a group of orphaned young architects without commissions were forced to make their way in a professional environment that was anything but challenging. Such was the climate in which the protagonists of this book found themselves.

2015. Architects of the 1974-generation, as well as younger (particularly Flemish) Belgian architects are winning competitions abroad. They are invited to teach at highly qualified international architectural schools, to exhibit their work, to curate exhibitions and to give lectures. Foreign architectural magazines publish on architecture in Flanders. [5] What has happened in the last four decades? How could an architectural culture develop in Flanders that is influential abroad? What characterizes this culture and who has played a leading role? [6]

A Burgeoning Architectural Culture

In hindsight it seems that two moments in 1983 proved important to recent architecture in Belgium. At that time the Carrefour de l’Europe was the subject of the Bonduelle competition, according to Geert Bekaert this was the first time the new generation could brandish their talents in a public architecture commission. In addition to the acclaimed Georges Baines, the architects Jo Crepain, Georges Volcrick and the Hoogpoort team (Stéphane Beel, Xaveer De Geyter, Arjan Karssenberg and Willem Jan Neutelings) submitted entries. The competition did not pass without discussion, because the results demonstrated the potential that existed to turn this blot on the Brussels North-South Connection into a lively, urban setting. Despite the dynamic unleashed by the competition, the Carrefour de l’Europe ended up being privatized and cheapened by pastiche hotel architecture that stemmed from a tangle of political interference and lobbying by promoters. This was tremendously disappointing.

In 1983 too, Marc Dubois and Christian Kieckens set up the Architecture Museum Foundation (S/AM), which had a far-reaching effect on the development of an architectural culture. S/AM functioned as a platform for discussion about architecture. Its exhibitions and publications provided a stage for young architects whose relatively small commissions from ‘enlightened’ clients enabled them to experiment and almost soundlessly they changed the course of architecture in Flanders. Additionally, S/AM organized foreign trips to inspiring examples of architecture. The foundation’s magazine evolved from a fairly amateurish rag to a respectable series of architectural monographs. Along with an international program of lectures these publications satisfied the architects’ demands for foreign and historical references and for criticism, information and reflection on architecture. [7]

S/AM was not the first of Dubois and Kieckens’ initiatives. In 1977, at the age of 27, Dubois became one of the youngest members ever of the Royal Commission for Monuments and Landscapes. [8] He was also involved in founding the architectural association Archipel in 1979, and Interbellum in 1980, another non-profit organization dedicated to the study and conservation of valuable patrimonial heritage from the 1920s and 1930s. In 1980 Dubois began to publish articles in Wonen TA/BK, where he frequently expressed his interest in contemporary architecture, architectural history and the preservation of historic buildings. He wrote about the legacy of modernism in Belgium, studying figures such as Gaston Eysselinck (1907-1953), and about contemporary architecture and (the lack of) government policy in this area. More than ten years later, when publishing the first Flanders Architectural Yearbook in 1994, he noted that in his eyes architectural culture meant ‘the creation of conditions to enable the development of an architectural culture, a culture cultivated on historical reflection and topical critique’. [9] From the very beginning this layering of ideas was present in his efforts to nurture an architectural culture and help generate awareness for the built environment. Before the foundation of S/AM, Christian Kieckens had also proven to be an architect who not only looked to the present and the future, but also used valuable elements from the past, when honoring his intellectual patron Pieter De Bruyne (1931-1987) in 1981. The two founders of S/AM had never intended to gloss the past with nostalgia, but to study it in order to translate its qualities to the present. How they might lend shape to this in a contemporary way was the challenge that Kieckens and Dubois took on. In addition, Kieckens sought to discover the boundaries of architecture as a discipline, by, inter alia, incorporating visual art and design. He was more inclined than was Dubois to bring his interest in art to bear on his architectural research. These two lines, i.e. historical reflection and dialogue with the visual arts, were extended by two initiatives in Ghent in the second half of the 1980s.

In 1986 the arts events Initiatief 86 and Chambres d’Amis took place in Ghent. For the Chambres d’Amis, artists created works of art in private homes that often intentionally reflected on the surrounding architecture where the piece of art was created. Luc Deleu’s art installation of two power pylons on St. Peter’s Square, Paul Robbrecht en Hilde Daem’s scenography for a section of the Initiatief 86 group exhibition and Charles Vandenhove’s intervention on the 16th -century façade of the Museum of Decorative Art made it quite clear that architects could play a challenging role in the world of art. [10]

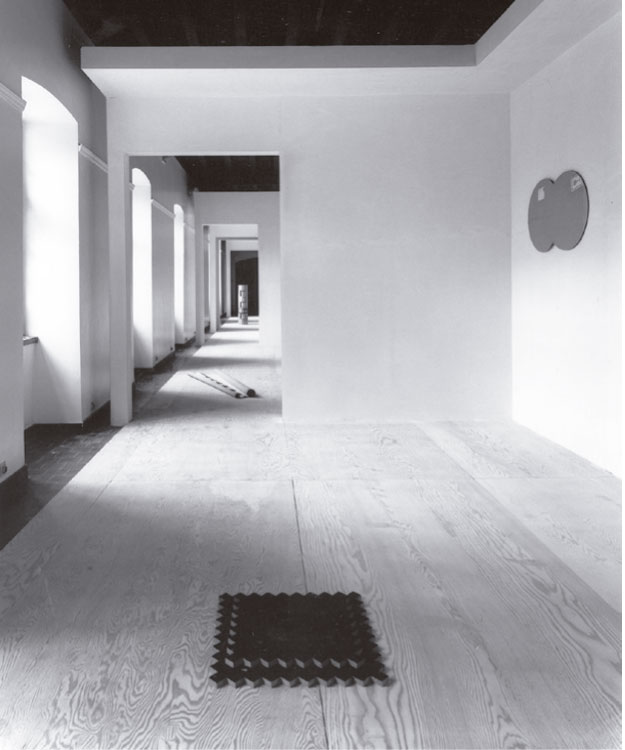

Robbrecht en Daem, Scenography, Initiatief 86, Sint-Pietersabdij, Ghent: works by René Heyvaert, 1986.

Photo by Piet Ysabie.

Two years later a new event in Ghent placed architecture itself center stage. Architectuur als Buur (Architecture as Neighbor) was an architectural festival organized by Architectuurpromotie, a non profit organization of several public and private organizations, such as the Union of Architects, the Historic Buildings and City Archaeology Department of the City of Ghent, the S/AM, the Royal Association of Master Builders of East-Flanders and the National Association of Architects. The highlights of the event were an exhibition, visits to interesting buildings, a debate, a publication and an architecture guide, all of which had clear educational objectives. The architectural festival sought to be a ‘call to create a positive architectural climate, in which a collective sense of responsibility would lead to a high quality urban development and architectural modernization process’. It used the ‘strategy of creating a broad public platform to discuss contemporary architecture.’ [11] Notably, the administration of the city was aware of the city’s responsibility concerning contemporary architecture, given its role as both commissioner, and as the administration for approval (or rejection) of building permissions. From an administrative viewpoint it took quite some time before an official response came to the underlying demands of Architectuur als Buur, through the foundation of the unit of architecture at the Historic Buildings Department, a relatively independent urban development service and the Chamber of Quality. What did come fairly quickly was a tax on abandonment. The main effect of Architectuur als Buur in the short term was that public awareness for contemporary architecture grew, and that architecture was taken seriously as a cultural discipline. Young architects were given interesting private commissions, partly because of the attention the event received in popular media. In hindsight Architectuur als Buur functioned as a catalyst for the many town festivals and architectural events that became popular in Flanders in the 1990s and through which urban (re) discoveries and city development became linked to tourism and the promotion of the city.

In the meantime, in the mid 1980s, an initiative originated in Antwerp that would make an enduring contribution to the burgeoning architectural culture. Under the directorship of Frie Leysen, the international arts center deSingel launched a series of architectural exhibitions in 1985. Architectural programmer Carolina De Backer worked in close collaboration with Geert Bekaert and Mil de Kooning. The deSingel exhibition program featured Belgian architects such as Charles Vandenhove (1986), AWG (1987), Luc Deleu (1987), Marc Dessauvage (1987), Paul Robbrecht and Hilde Daem (1989) alongside international designers such as OMA in 1985, Aldo Rossi in 1986 and Luigi Snozzi in 1989. In addition, themed exhibitions focused on topical subjects through reflection on the past, such as ‘Adolf Loos – Le Corbusier. Raumplan versus plan libre’ in 1987-88. This gave architecture a place in the arts scene and the arts center devoted resources to professional architectural activities, something that remained quite unique for many years. Soon a synergetic relationship grew between the S/AM and deSingel, and in the spring of 1988 the exhibition entitled ‘Young Architects in Belgium’ presented the S/AM’s selections from 1985 to 1987. At the opening of this exhibition Jo Crepain read a letter to four ministers out loud, in which he pleaded on behalf of ‘28 angry young men’ for good clientship and for a system of public competitions in which quality (and not political relations) were the most important criteria. [12] The action of this group of young architects, who had nothing to lose, showed how critical questions and demands could be expressed to policymakers from the refuge of a cultural niche.

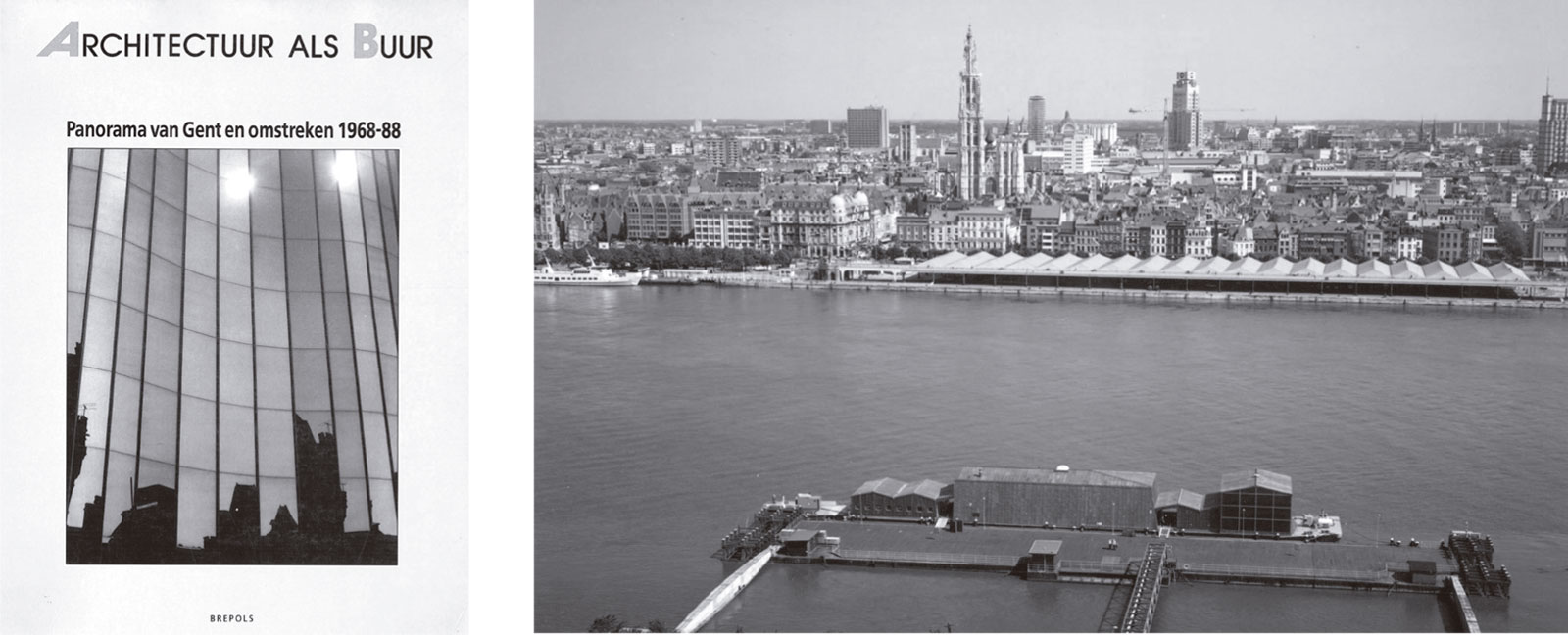

Architectuur als Buur. Panorama view of Ghent and surroundings (Turnhout: Brepols, 1988).

AWG Architecten, Floating Theater De Ark, Antwerp, 1993. Archive AWG Architecten.

Photo by Wim Van Nueten.

Gathering Momentum

A year after Crepain’s statement at deSingel there was hope of an about-face. In 1989, nine renowned architects from Belgium and abroad were invited to take part in a restricted competition for the construction of a new Sea Terminal in Zeebrugge. Projects were submitted by Rem Koolhaas, Charles Vandenhove, Fumihiko Maki, Aldo Rossi in association with Claude Zuber, and bOb Van Reeth. Although Geert Bekaert described the competition as an ‘innovation’ and a ‘point at which the Zeebrugge policy gave rise to a hope that architecture would be taken seriously in Belgium’, the project wasn’t realized. [13] But things seemed to be gaining momentum and initiatives followed in ever-quicker succession, including architectural competitions and shows on architecture from Flanders, both at international and local platforms. It seemed that change might actually be possible. Following the letter of the ‘28 angry young men’ in deSingel, the S/AM managed to sweep from the table a clichéd design for the Belgian pavilion at the World Exhibition in Seville, and the contract was won on the back of a public competition (1991) by the young firm of Giedo Driesen, Jan Meersman and Jan Thomaes.

The dynamic caught on in smaller Flemish towns and cities. Local architectural associations such as Architectuurwijzer (1991) and Stad en Architectuur (1997) were formed and city councils set up competitions. In 1990, for example, Kortrijk and the inter-municipal organization Leiedal invited tenders for the development of Hoog-Kortrijk, a contract that was won by Bernardo Secchi. With its Domus Flandria project the Flemish government hoped in 1990 to catch up on its social housing stock, and sought to employ good architecture in the process. In Ghent, for example, a project for 129 social housing units on the Hollainkazerne site was awarded to Willem Jan Neutelings following a competition in 1993. Competitions for Wonen in Gent (WIG) and the WISH competitions organized by the Minister for Housing, Mr Buchmann, originally sparked hope of better architecture through a public procedure, although the results turned out to be a disappointment when local networking swayed the decision-making process. [14]

Of a different magnitude and with a greater impact on later developments was Stad aan de Stroom in Antwerp. This study group, which was made up of architects, civil engineers and representatives of civil society, sought to generate ideas through an international architectural competition for the districts Het Eilandje, Zuid and the Scheldekaaien, three former port areas that were in decline following the loss of harbor activities nearby the city center in the 20th century. The competitions were a success: invited international designers submitted proposals for the three former harbor districts. The competition also boosted the local architectural dynamic since more than 100 young Belgian architects submitted proposals. There was a public debate on the feasibility and desirability of the projects, and in 1992 two detailed proposals (from Toyo Ito for Zuid and from Manuel de Solà-Morales for Het Eilandje) were approved in principle by the city council and presented to the public.

One of the effects was that architecture was given a central position in the Antwerp Cultural Capital of Europe ‘93 program, under the program Studio Open Stad that was curated by Pieter Uyttenhove. The focus lay on urban culture, through which the city’s past, its image and representation, and research by design were connected to each other. The 19th -century city belt became the working space in which these three pillars were developed. Antwerp ‘93 and Stad aan de Stroom were extremely important to the architectural climate in Flanders. Neither of the two events led to specific architectural or urban projects in the short term (only general disappointment in the decisiveness of politics where Stad aan de Stroom was concerned), with the exception of a few significant restorations (such as the Bourla Schouwburg) or one-off projects in the city, such as the Ark, a 77-meter floating theatre/café designed by AWG for Antwerp ‘93. But they both lent a powerful impetus to the rediscovery of the city as a place of economic and cultural activity and creativity, to public awareness, to a vision for urban development and the role that architecture can play in this. In addition, Studio Open Stad served as a catalyst for getting the various Belgian architectural schools to rethink urban problems, by bringing together research by design, historical reflection and the theoretical basics of architecture and urban development. [15] Studio Open Stad remained operational for ten years after Antwerp ‘93 and turned its attention to Brussels, where the arts center Beursschouwburg played a prominent role as its host.

While it became increasingly obvious that foreign architects should be asked to develop plans and conduct discussions in Flanders in the early 1990s, architecture from Flanders was also able to hold its own in an international context. Meanwhile the discourse on contemporary architecture took a noticeable swing from ‘Belgium’ to ‘Flanders’. Whereas the term ‘Belgian’ architecture had been used until the late 1980s, and the exhibitions organized by S/AM were entitled ‘Young architects from Belgium’, the focus quietly shifted towards architecture from Flanders. This shift was linked with the Belgian State’s federalization into Communities and Regions, which was first felt in the domains of education and culture. Given the fact that the young architectural culture in Flanders was able to unfurl in the wake of a dynamic set up by cultural players, for example through its embedding in deSingel and its association with urban culture festivals, architects looked primarily to new possibilities that the emancipatory Flemish cultural policy created. With Flanders’ newfound independence and the installation of its own government ministers, including a minister for Culture, it made more sense for architecture to profile itself as ‘Flemish’ rather than ‘Belgian’. Indeed, it may have had more to do with opportunities and finding resources for (international) presentations, and with the possibility of winning contracts, than with a strong political ideology. Moreover, the growing interest in urban culture in Flanders, through events like Chambres d’Amis, Architectuur als Buur or Antwerp ‘93, was more than a decade ahead of French-speaking Belgium. On the other hand, the continuity of historical architectural culture was much greater in French-speaking Belgium, due to for example the emancipatory role of the La Cambre school of architecture, which was a reflection of Bauhaus’ avant-garde education. [16]

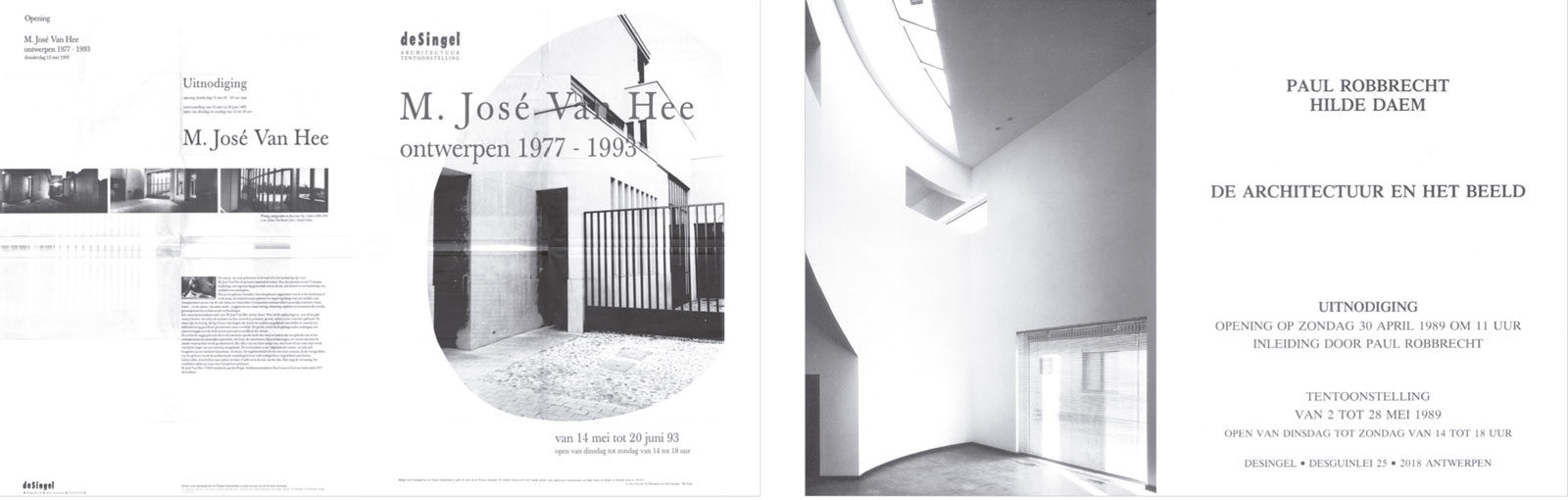

Poster invitations deSingel: Van Hee, Robbrecht en Daem, Kieckens, and Herzog De Meuron.

Archive deSingel.

The fact that education was no longer organized by the Belgian government under the state reform of 1988-89, but shifted to the Flemish and French-speaking Communities, helped remove even more of the formal ties between Dutch-speaking and French-speaking architects. This does not mean that architectural developments across the language border were ignored: figures such as Charles Vandenhove and Bruno Albert were still important in Flanders. A big difference between developments in Flanders and French-speaking Belgium was that the evolution in the south of the country was associated with works and figures who were much less concerned with the culture around architecture than was the case in Flanders, despite the fact that on the initiative of architect Philippe Rotthier the Fondation pour l’Architecture was set up in Brussels in 1986 to disseminate an architectural culture through exhibitions and publications. [17] In this dual speed landscape of federalization, the Belgian magazine A+, which issued parallel editions in French and Dutch, played a connecting role as an island between the two cultural communities.

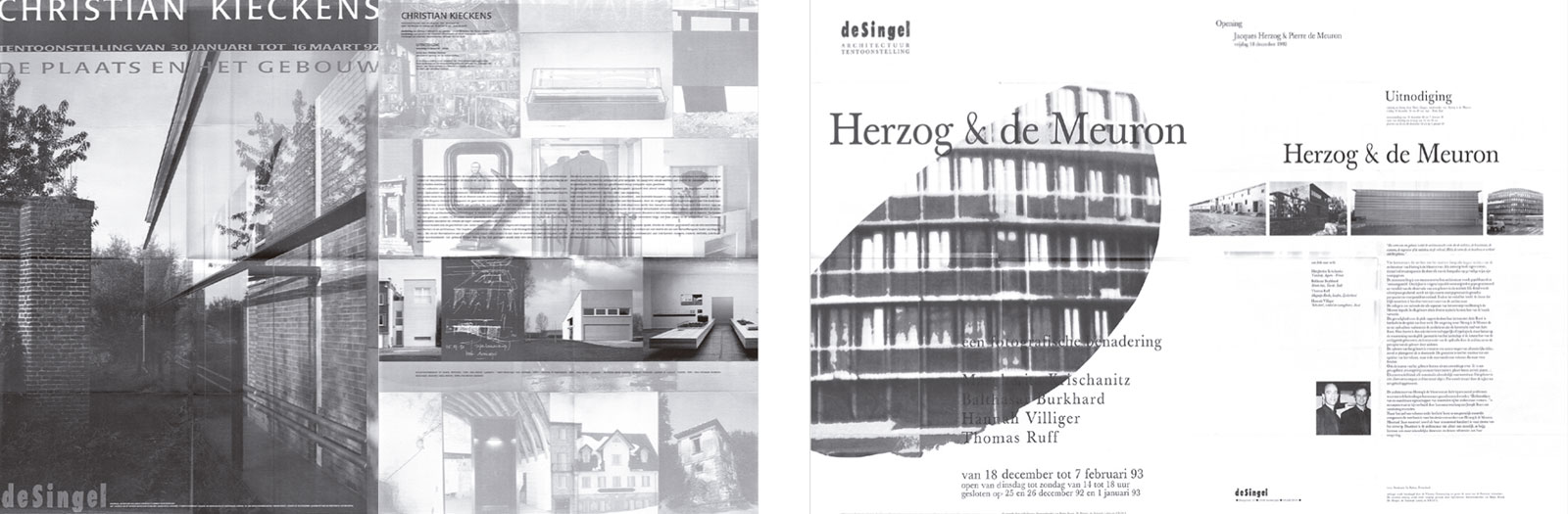

Christian Kieckens, installation ‘Table-landscape’, deSingel, Antwerp, 1997.

Photo by Reiner Lautwein.

The state reforms implied that there were two speeds and strategies in support of an architectural culture, one on each side of the language border. The succession of state reforms and the emancipation of Flanders made it worthwhile for Flemish policymakers to employ a cultural policy that placed Flanders on the international map. In 1990 the Flemish Community invested for the first time in presenting Flemish architects at an international forum in Berlin and Moscow, using retakes of deSingel exhibitions by Luc Deleu (T.O.P Office), bOb Van Reeth (AWG) and Stéphane Beel. However, more significant was Flanders’ first participation in the Venice Architecture Biennale in 1991. Marc Dubois had persuaded the minister of Culture, Patrick Dewael, of the importance of the presence of the Flemish Community at this international architectural event, and was appointed as curator. Christian Kieckens’ sober and subservient scenography was used to display works by Paul Robbrecht en Hilde Daem, Marie-José Van Hee and other architects of their generation. Artist Johan Van Geluwe brought the surrealist Belgian undertone to light for an international audience, to evoke the context in which architects worked in Flanders. The exhibition did not go unnoticed. Two years later Italian publisher Electa produced an overview of architecture in Belgium since 1970, and in 1994 the French journal Architecture d’Aujourd’hui dedicated a special issue to architectural developments in Flanders.

Flemish designers seemed able to enter the international architectural scene with a new flair and self-confidence. Cultural projects were a major instigator. From 1990 onwards, the exhibition policy at deSingel, curated by Katrien Vandermarliere, rested on several cornerstones: monographic exhibitions of work by the young generation of Flemish architects and quirky post-war modernists, high-profile international designers and related disciplines that broadened the perspective of architecture, such as landscape, art and photography. The exhibition space in the Léon Stynen building – 80-metre long and 6-metre wide corridor – invited the architects to address the scenography as an architectural intervention. Along with this exhibition program deSingel steadily built up a series of architectural publications which were later taken up by publishers Ludion and Lannoo. With exhibitions such as ‘Mein erstes Haus’ (Amsterdam 1994), ‘Nouvelle architecture en Flandre’ (Arc-en-Rêve, Bordeaux 1997) and ‘Homeward’ (which took place in six European cities and the Venice Biennale 1999-2000), deSingel picked up where S/AM had left off after its dissolution in 1993, as regards the international presentation of Flemish architecture. [18] With the professional organization of an international arts center behind it, Flemish architecture had the capacity to be contrasted, discussed and even held up as an example at international forums. In addition, deSingel offered the space and freedom to help shape the burgeoning architectural policy from a critical perspective. In the meantime, Dubois continued his work as a critic and curator and kept on making efforts to win international recognition for Flemish architects. For example in 1997, he curated the exhibition Arquitectura de Flandres in the Col.legi de Arquitectes de Catalunya in Barcelona.

Architectural Culture as the Catalyst for Policy

While architects, lecturers, critics and cultural professionals were building an architectural culture from the ground up, they continued to press for structural government support for quality in architecture. The international exchange helped get things going on a structural level. Architecture may have withstood comparison to neighboring countries to some degree, at the same time the official architectural policy faltered on crucial aspects, such as the procedures for awarding projects, the quality of public contracts, an appropriate urban development framework, the opportunity to carry out innovative research and the lack of possibilities to publish on architecture. However, the political emancipation of Flanders offered real potential in those areas. In 1992 the Flemish coalition agreement stated for the first time that ‘architecture and design must be given a place in culture policy’. [19] The fact that in all that time the most spectacular steps in the development of an architectural culture had taken place in arts centers and at events, now received permanent recognition and possibilities were created for the story to further unfold. An Architecture Study Group started to operate from the Visual Arts and Museums department of the ministry of the Flemish Community and worked on developing an architectural policy. [20] In addition, resources were earmarked for cultural projects on architecture and for (international) grants, and a newly formed Architecture and Design Commission assessed the quality of the applications.

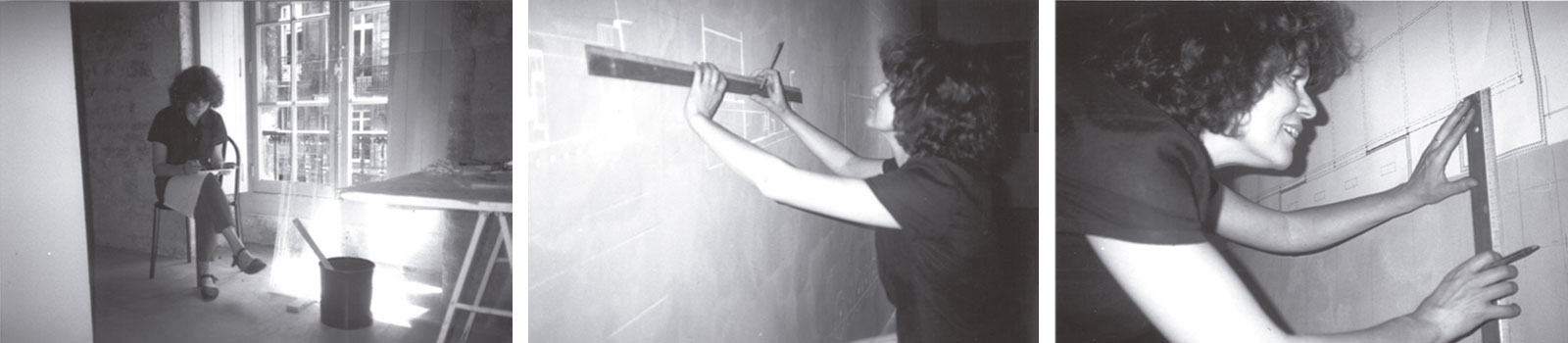

Marie-José Van Hee, Installation in Bordeaux, 1996.

Archive Marie-José Van Hee architecten.

Also in 1992, Stéphane Beel became the first architect to win a Flemish Community culture prize. Since architecture did not have a ‘prize of its own’, Beel received the prize for visual arts. This recognition of the cultural importance of architecture became permanent when the Flemish Community biennial cultural prize for architecture was introduced in 1995. [21] Also the publication of the first Flanders Architectural Yearbook in 1994 was a breakthrough: from then on there was a permanent tool to hand to analyze the better projects, to start a dialogue on the subject of architecture with policymakers and the general public, and to broadcast recent developments in Flanders abroad. Over the same period Johan Sauwens, minister for Monuments and Sites, made up ground in the area of historical buildings preservation by protecting a large number of monuments, and in 1993 awarding the first Flemish Community monument prize. Historical building preservation and qualitative contemporary architecture were firm allies in the fight for a better architectural climate. This was evidenced once again at a workshop on ‘Public buildings and space: a cultural challenge’ in Antwerp in 1995, an organization set up by the Open Monument Day Coordinating Committee, the Flemish Community’s Art administration and deSingel. [22] It was articulated that contemporary architecture and historical building preservation were strongly linked as a fecund medium for a lively architectural culture and as the basis for an integral vision on the quality of the built environment. It was quite clear that environmental planning had a role to play here too. With the approval of the Ruimtelijk Structuurplan for Flanders in 1997, a general spatial zoning plan for the entire region of Flanders, hope grew of bringing into practice an alternative for urban sprawl, the spread of business parks, roads and allotments, which had led to the degeneration of the landscape in Flanders.

In the years before, architects had stressed the necessity to award contracts on the basis of public competitions. The international architecture competition for the renovation of the Beursschouwburg in Brussels in 1997, won by B-Architecten, was a turning point in this. The theatre, with the Flemish Community behind it, revealed itself as an exemplary commissioner and gave hope of a fundamental turnaround. [23] This came one year later when the minister for Finance, Budget and Health, Wivina Demeester, established the Flemish Government Architect (Vlaams Bouwmeester). In the early years, the Flemish Government Architect set up procedures to stimulate the quality of public architecture. This generated a snowball effect of interesting projects and building sites through which the young guard and established architectural firms were given opportunities to create public buildings. These opportunities grew again after 2002 with the installation of Stedenbeleid, an integral urban policy through which strategic urban renewal projects could effectively be realized in 13 Flemish cities. [24]

Bernardo Secchi & Paola Vigano, Spoor Noord, Antwerp.

Photo by Stijn Bollaert for Flanders.

Architectural Yearbook 2008-2009 edition 2010: 106-117.

In the meantime the minister of Culture, Luc Martens, had completed his preparations for the foundation of the Flanders Architecture Institute (VAi). His successor Bert Anciaux inaugurated the VAi in 2001. The VAi was given the tasks of handling the biennial publication of the Flanders Architectural Yearbook and organizing Architecture Day. The idea was established that the quality of the built environment rests not only on the level of the contemporary architecture but also on knowledge and respect for the past, and in 2003 the Centre for Flemish Architectural Archives (CVAa) was incorporated within the VAi. The VAi and CVAa were housed in deSingel and so their incorporation in the arts center continued.

An (Interim) Balance

This article discusses how, as the result of cultural projects and events on architecture, and following the public commotion in relation to certain commissions and competitions, a process of emancipation took place in which Flemish architectural culture reached adulthood. Of course, this focus on the genesis of the contemporary architectural culture through a cultural program of exhibitions, journeys and events cannot be viewed separately from other developments, which also contributed to the current dynamic of the architectural culture. For example, architectural education evolved in the same period, through, inter alia, the development of research by design and the installation of chairs of architectural theory, and there were important initiatives such as the Vlees & Beton publication series. The history of the present architectural culture is also closely connected to the way in which architecture was discussed in newspapers and other popular media by critics like Geert Bekaert, Mil De Kooning, Marc Dubois, Hilde Heynen, Francis Strauven, Paul Vermeulen and Koen Van Synghel. The sector of art and design also led to intellectual exchange and to opportunities to critically assess architecture, including the efforts of the Interior Foundation in Kortrijk, with its design competitions, guest curators and commissions for scenography, and with the foundation of the Centre for Architecture and Design in 1996, in which Marc Dubois was involved. [25] All these initiatives contributed to public debate and awareness of the added social value of qualitative architecture.

Cover Flanders Architectural Yearbook 1990-1993, first edition.

Cover, presentation of Team Vlaams Bouwmeester. De Zutter, Jan and Team van de Vlaams Bouwmeester, Een bouwmeester bouwt niet. (Brussel: Ministerie van de Vlaamse Gemeenschap Vlaams Bouwmeester, 2004).

What makes the evolution fascinating from the perspective of a cultural policy on architecture is that the architects involved were always expected to engage in a process of intellectual input and of exchange with contemporary artists. This created a tension between the actual building process on the one hand, and the development of a more theoretical discourse on the other. The incorporation of programming architecture in cultural institutions was important for this, and possibly a determining factor, in continuing to enrich the architectural scene. It created the possibility of permanently challenging experiments, multilingualism, peculiarity and criticism. The freedom to program architecture in a cultural institute did not imply practical or political restrictions in setting ambitions, however unachievable they might have seemed at the time. Exotic countries and neighboring countries could offer inspiration or could be held up as a conceptual standard, without having to wonder if this was realistic. It seemed that the cultural framework was a playground or laboratory in which foreign standards could be measured against the Flemish context, in order to develop a proper idiom. All levels of scale in design could be treated in the same way: from furniture and scenography to architecture, infrastructure, urban development and landscape, and even related arts like photography and film. But there was a clear agenda behind the cultural architectural programing, which sought to have an impact on the building process itself. Not only did it bring a broad audience, including future clients and policy makers, into contact with architects through exhibitions and lectures. Often the same architects were invited to advise the government on developing an appropriate architectural policy.

This model was strongly entwined with the dynamic in visual arts, theatre and fashion in Flanders, and differed greatly from the developments that were taking place in other countries. Architectural policy in France supported ‘Grands Projets’ for Paris and the major cities, which then built cultural infrastructure through large international competitions, such as the FRACs. In time this top-down approach led to what is probably the biggest architecture institute in the world, the Cité de l’architecture et du patrimoine, in Paris. As opposed to Flanders, the connections with contemporary architectural education and art, and a critical disposition were not as high on the agenda. The Netherlands also had a blossoming architectural policy in that period and garnered international attention for years through the image it cleverly created around the architecture of several larger firms that completely dominated the architectural debate. Under the ‘Superdutch’ denominator the Netherlands focused almost exclusively on object-related architecture with a pronounced contemporary idiom. [26] At the same time an accommodating grant system supported a large section of the architectural corps, which produced research studies and publications. The Dutch Architecture Institute (NAi) was the elder, much bigger and stronger brother of the VAi, which helped promote Dutch architecture internationally.

Against these top-down models of the neighboring countries, stood the Flemish architectural scene, being smaller and the result of a series of bottom-up initiatives, but nonetheless ensuring that the discourse on architecture was always lively, alert and international, feeding itself with historical reflection, a strong relationship with architectural education, mutual influences with other arts and critical debate. Herein lies the legacy of the S/AM. From the very outset the S/AM strove for international exchange, originally due to the lack of interesting developments in Flanders/Belgium. Foreign architecture and architectural policy were initially admired with envy, later to be critically analyzed. It gradually became apparent that the Flemish architectural scene could actually withstand international comparison. Self-confidence grew, and was used to convince policy makers. Also in this, the S/AM went ahead. From the 1980s on, it had always tried to be closely connected to policy preparations. In open debate and behind the scenes it helped think of ways in which architectural policy might be shaped, and about the appropriate values and instruments for this. Finally, the permanent concern for new generations of architects is a third aspect of architectural culture in Flanders that was initiated by S/AM, and was later continued by deSingel and VAi amongst others. In the cultural realm of exhibitions and series of lectures, young designers are always given opportunities. Taking the lead in this with its much talked about series of ‘Young Architects’ exhibitions, the S/AM is without doubt the fountainhead of Flanders’ present architectural culture.