During the historical processes of civilizations, the morphology of cities has served as one of the most useful tools to study and analyze the social, political, economic, productive and cultural ethos of previous, and possibly posterior, societies. The materialistic condition of the cities brings together various abstract conceptions such as the political and the economic, whose dialectic foundation seizes a common ground towards and within the city.If we scrutinize the emergence, development and consolidation of cities through the conceptual framework of historical materialism [Marx: 1959], we can argue that production and its subsequent exchange of goods is the basis of all social order. In all societies throughout history, goods distribution and the social division is determined by what the society produces, how it produces, and the mode in which the products are interchanged. This notion is subsequently transformed and shaped in the means of inhabitation, the city.

After revising this particular historical context, we can deliberate on the importance of the productive notion and its synergy with all the economic apparatus and how its abstraction reflects and materializes truthfully in cities. Nevertheless, how can we demonstrate this thesis in a collective or individual case study? In which society do we find a notorious and disruptive course, where the city morphology changed along with its production system?

The answer lies in the Latin American case, where after the establishment of the Spanish Viceroy (1542), the distributed and diversified production system of the native cultures shifted to a centralized economy, based on mercantilism and interventionism. This cultural and productive disturbances produced a standard layout for the intervened cities, whose contemporary reality and morphology share remarkable and disturbing coincidences; the result of obsolete economies in the contemporary context.

Continental Outsourcing

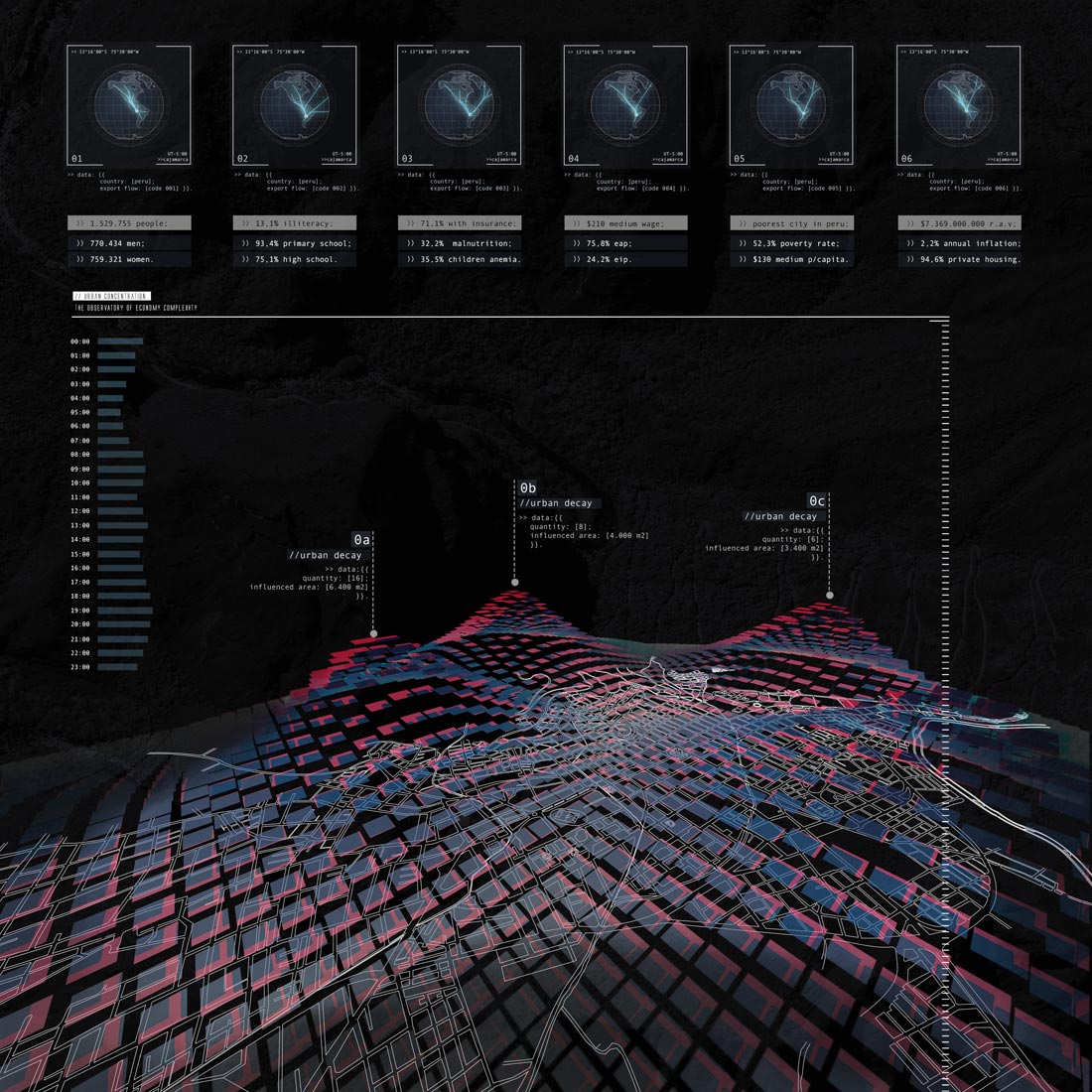

The repercussion of centralized economies in the South American continent is directly reflected in social indicators that determine the quality of life of the current citizens. These indicators such as inequality, poverty, illiteracy, high mortality rates and environmental pollution are incompatible with the centralized condition of the economic system; they are distributed all over the cities. The capitals of the countries that were once the developing poles of the Viceroy are now the cities that concentrate the highest rates of economic income and development. The equation is simple: profit concentration and loss distribution. This problematic exalts the historical antagonism between the city and the countryside, where the countryside becomes the anchor of the extractive economies, and the city plays its role by concentrating the economic capital.

The status quo fosters civil confrontations that polarize the extractive companies and the communities around them, emphasizing the historical struggle between economic and social capital. In the following charts we can underline these two indicators – the extractive zones and the civil associations against extractive economies – and how they naturally match in the territory.

Social Affection vs. Extractive Economies

The Cajamarca Paradox

As an attempt to delve into the problematic of the extractive economies, I chose a Peruvian city whose main production system is based on commodities, related to the extraction of minerals, hydrocarbon and raw matter. The GDP of this city once reached nearly US$7.5 billion. Nevertheless, the city presents a poverty rate of 64% and 29% of extreme poverty. The paradox lies in the notion that the city actually doesn’t have an economic problem, but a political one. The productive policies emphasize the extractive economies, along with their social and environmental repercussions, over diversification.

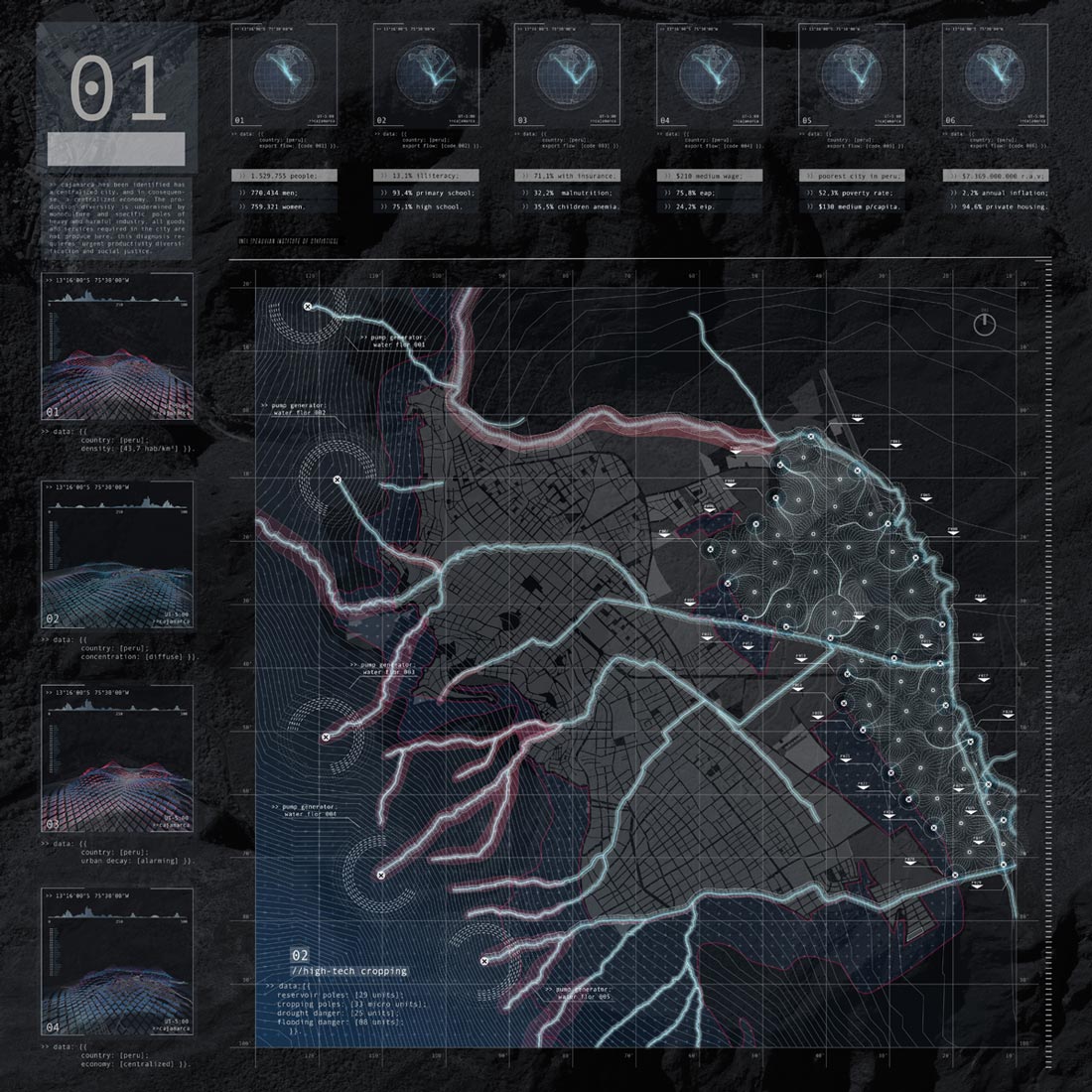

These policies produce a lack of potable water and irrigation systems in a city that is crossed by rivers and where 70% of the population is dedicated to agriculture. The mine that is located in the north of the city works as an attractor point for the social and economic dynamics that are concentrated mostly around the main square of the city. Its fragmented distribution and centralization represents a banal copy of the current economic system. The distributive policies of the city are not only absurd, but also paradoxical. Following the morphological study of the city, the diagnosis reveals a dependence on extractive economies, an alarming social detriment, and disablement of the energetic resources.

Urban Decay and Real-Time Detriment

The Laboratory of Economic Complexity

Economic complexity is a holistic measure of large economic systems that conveys the amount of knowledge of the population and its direct effect on the country’s industrial composition. With more knowledge among the population and their exposure to challenging and stimulating tasks, the more complex the production system becomes.

Is this type of economic notion viable in a city where the production system reduces the capacity of the labor force to work on monotonous and non-heuristic tasks? I believe so.

The problem with extractive cities is that this activity in the economic chain of production demands 75% of labor hours for the production process (extraction–transformation–distribution) and receives 10% of the revenue. On the other hand, the transformation of the raw material into final products demands qualified personnel and covers only 5% of labor hours, receiving around the 80% of the final income. This clear reality became paradigmatic during the processes of industrialization as one of the biggest inputs toward the expansion and consolidation of western countries, as well as their capacity to reinforce their industrial policies over time and the development of a protectionist character.

The question that arises lies in the possibility of starting a process of industrialization in Cajamarca via the economic complexity indicator. Along with this question, there is the issue of the capability of this indicator to become vital so as to be considered the aggregate value in the productive chain of Cajamarca. Then will it be possible to achieve a diversified and distributed economy? I believe so.

Resources and Objectified Interests

The city of Cajamarca is located in the foothills of the Andes Mountains and as a consequence it has a huge variety of energetic and mineral resources. In terms of solar radiation, its indicators fluctuate around 1909.08 KWh and 1790.00 KWh during the entire year. The wind blows at around 22.21 m/s and the water flow that rises in the Andes Mountains has the capability and the potential to act as a hydroelectric plant and produce around 5000 KWh. These numbers just represent the potential of the territory and its geomorphic conditions in order to produce enough energy over the year. The current energetic production of the city is rooted in hydropower (48%), wind power (0,6%) and the remaining 51,4% is contracted from private companies. The total amount of energy production of the city reaches 224.438 MW per year when the real demand claims around 349.183 MW, taking into consideration that the current population according to the last national census is 246,536 people.

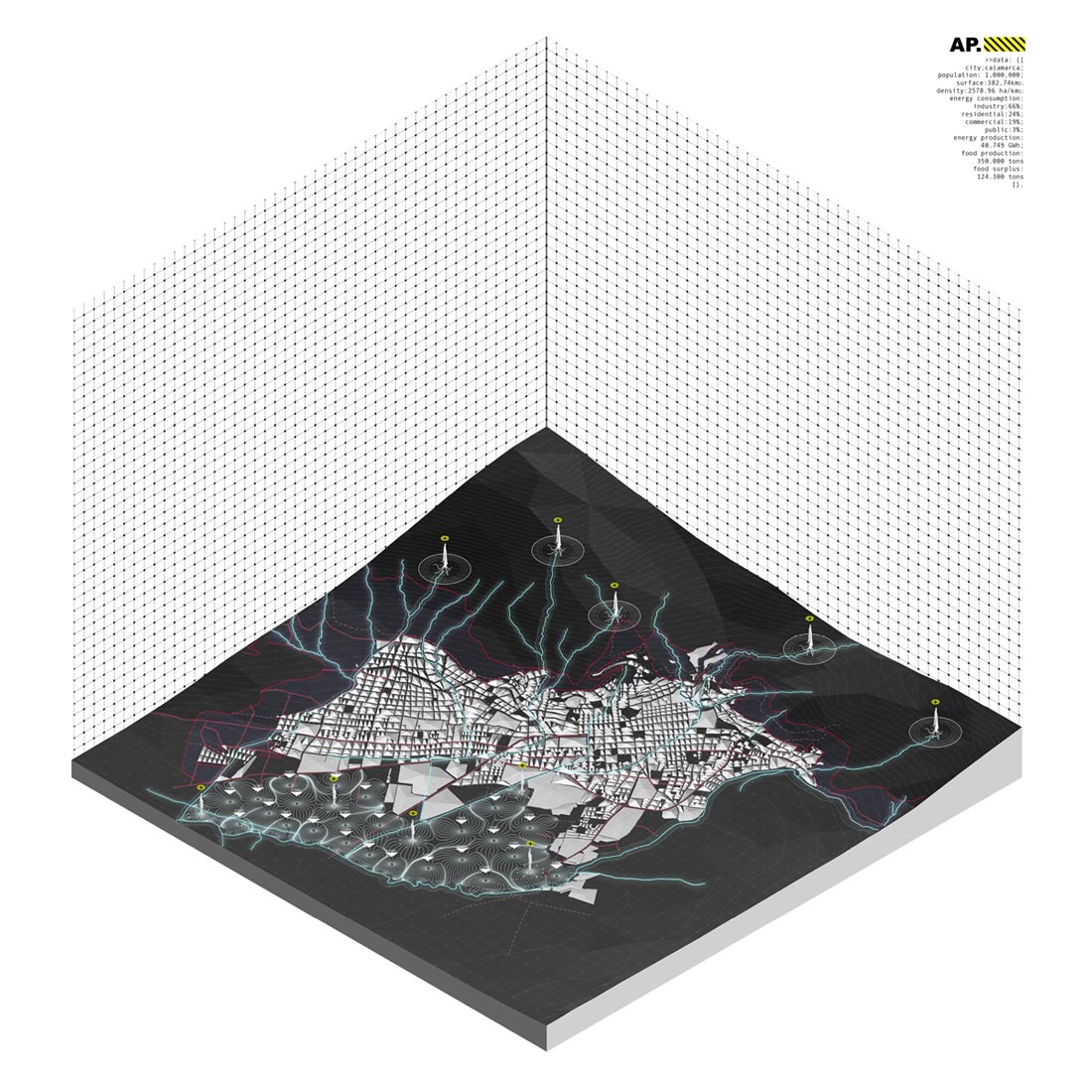

The energy distribution policies prioritize industrial use, with 66%, followed by the residential (24%) and the commercial (19%), relegating the public use to 3%. At the same time, there is no interest from the city governance to activate the energetic agenda due to private interests that gain tremendous revenues from the sale and trade of energetic goods such as electricity and heating.

The proposal of this research does not intend to implement specific or isolated mechanisms, but to transform the abstraction of energy polices into distributed and integrated networks that, working together alongside a social dynamics, could possibly reach a certain autonomy. The systems chosen for the new network respond directly to the energetic resources explained before.

To exploit the solar radiation, the devices that perform more adequately are transparent solar panels, photovoltaic panels and solar thermal panels, which can produce 3,711 KWh per day; these panels will be deployed towards the city based on the solar radiation analysis and the amount of square meters that represent the built space of the territory. After defining the five poles with the greatest water flow and with the capacity to perform as hydropower plants, the amount of energy that could be achieved is around 5,000 KWh per day. The speed of the wind flow is not adequate to gain energy with conventional systems such as the wind turbines; nevertheless, its flow its constant during the entire year. The obtainment of this resource lies in the capacity to harvest the low frequency waves that it produces. With this technique, it is possible to obtain around 54,000 KWh per year according to the wind analysis measurements, almost the same amount as the conventional systems.

With these three systems working as a network, it is possible to produce around 40,749 GW per year, the sufficient amount of energy translated into electricity and heating to supply a growing population (up to 1 million people) for an entire year.

Production Diversification

70% of the population in Cajamarca works in agriculture, which represents 21% of the annual GDP. The issue with this productive system lies in its chain of production; 100% of agricultural workers dedicate their full time to seeding and harvesting, squandering the opportunity to add value (transformation into goods) to the productive chain. The transformation of these crops into final products demands proper infrastructure, trained professionals, technology and a complex distributive system that the city is not able to provide yet. The deficiency of the water policies, drought in the seeding periods and flooding in the harvesting period, jeopardizes the capacity of the citizens to perform their labor, upgrade its quality and diversify its applications. The proposal for the production diversification lies in understanding its logics and the social affections that came within. I do not intend to propose a perfect cropping system, but to implement a production network that synergistically converges into a system that associates the seeding, harvesting, and processing (transformation of goods). The agro production should not be segregated or isolated in the countryside or in the peripheries of the city. On the contrary, the different techniques should be deployed towards and within the urban fabric. For the agricultural diversification, I propose two different cropping systems that converge in the processing of the later two.

The first one consists in a network of aquaponic centers that are located in the natural avulsion of the rivers within the city. The only requirement for the system is a control perimeter that can host the fish, the crops and the water cycle. These demands are naturally met via the hydro morphology of the rivers and its natural bifurcations. The aquaponic network will deploy 22 new productive poles upon the rivers, which at the same time play the role of linear public spaces, resulting in a series of productive public spaces. The second system seeks to consolidate and upgrade the current crop fields, taking into consideration the problematic of flooding and drought. The proposal envisions a network of micro-flooding units that, during the flood season (January-March) will redistribute and store the water through vector fields and reservoir poles, respectively. On the other hand, when the water becomes scarce (October-December), the reservoir poles will redistribute the water through vector fields, providing a permanent water flow network throughout the entire year. The integration of these two cropping systems and the processing center will be able to produce 350,000 tons of food for the growing demography of the city (up to 1 million people) and a surplus of 124,300 tons for trading purposes.

Agro Productive Morphogenesis

This strategy attempts to challenge the water polices by the implementation of management logics that not only act as mechanic systems but also as way of city governance and to replace the monotonous and inconsequential labor work with a skilled and challenging one.

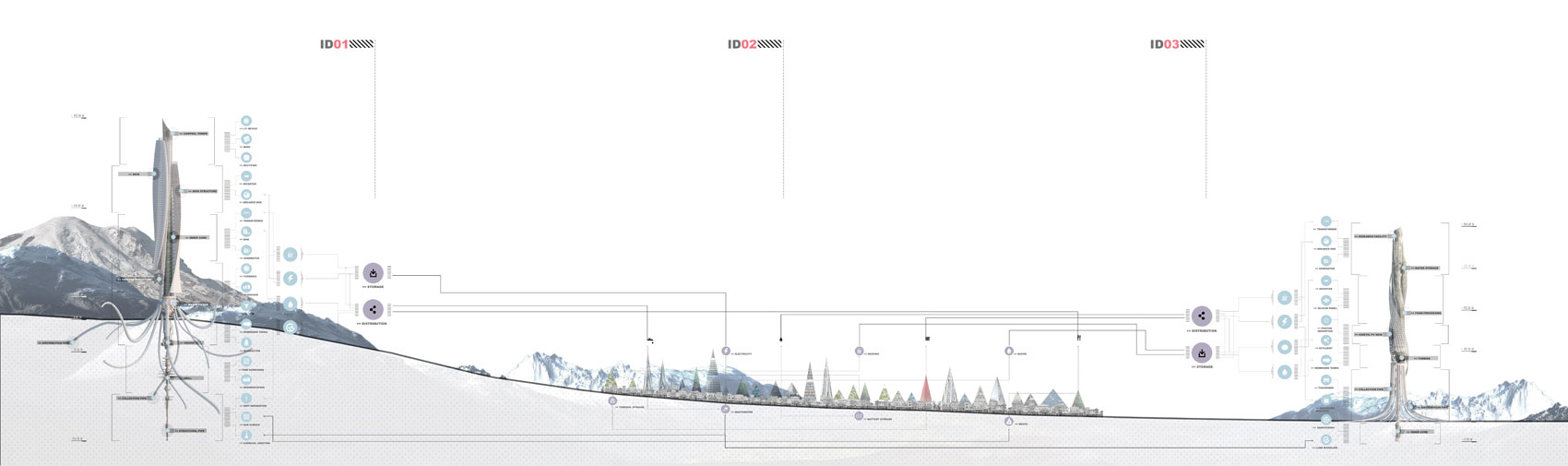

The Paradigm of City Architecture

The economic reconversion of the city and the deployment of the new logics will derive in a morphological alteration in the urban fabric of the city. These new logics can perform as predicted and produce energy, food and economic complexity in the productive system. Nevertheless, the question that arises lies in the conventionality/intentionality with which these artifacts will be deployed towards the city. For the hydropower, do we need conventional hydropower plants? And in the case of the water management, should we store and distribute the water in a conservative way? I believe not.

Paradigmatic Scenario

The metaphysical definition of a Machinic Assemblage refers to a system or body where its multiplicity and association with others defines its being. That this embodiment (system) should be valued for what it can do rather for what it is. (Deleuze: 1988) The hypothesis for a non-figurative architectural aesthetic for the city fights back the drama of newness with conceptual clarity and formal exemplarity. (DOGMA: 2008) The machinic archetype does what is meant to deliver.

Machinic Assemblage

The primary network of prosthetic devices will emulate the logics of a hydropower plant and will be located in the Andes Mountains. They will reinterpret the logics of a dam to obtain energy from the waterfall, pumping the water through the tower and realizing it without the detriment of destroying the mountain or changing its natural ecosystem by slightly standing on them.

Andes Defender

The secondary network of prosthetic devices will be allocated in the crop fields and will store and distribute the water in the intertwining seasons. It will store the water during the flooding and distribute it during the drought. It will also serve as the processing center for the transformation of goods, shifting the labor occupancy from harvesting and seeding to management and processing.

High-Tech Crop Field

The Autonomy Project seeks to envision the paradigmatic scenario in which the deployment of economic and productive logics becomes materialized towards and within the city.