Complexity often defines the density of the interactions between the elements of one or more systems. The more interaction there is, the more the complexity increases in some way. However, we must be careful not to confuse what is complex with what is complicated. Where the complex is a density of interactions, the complicated is just an accumulation of simple elements.

The world in which we evolve leads us to have a simple vision: we “analyze” a phenomenon in its instantaneity without invoking all the interactions that are linked to it. We live and see in the short term; we flee the long-term, and we end up stacking and never connect. Because it generally favors the short term, design for industry (design, production, communication, consumption) is a tool that promotes this simplification of the world. The current designer creates experiences, products and services that, at best, hide the complexity or, at worst, show disgust. Yet it seems more than necessary today not to be disgusted by the complexity of our world but rather to embrace it as best we can. It is through the personal attempt to understand the complex that we move away from the frenzied ignorance of those who think they know, and we leave behind the shores of superficiality. In short, to embrace the complex is to invite oneself to the journey. In this perspective, the practice of design can become an incredible tool for mediating complexity, because it naturally embeds one of the most complex (and thus most disturbing) elements of our world within its reflection: humanity.

Simple Thinking in Design

Before embarking on any notion of complexity, it seems relevant to define simplifying thinking (called disjunctive). It seems reasonable to begin our exploration in the 17th century: the thought of Descartes had a fundamental influence in the construction and organization of our knowledge, i.e., an organization by discipline. This thought is found in his Discourse on the Method in the form of precepts:

1. Do not receive anything for true until your mind has clearly and distinctly assimilated it beforehand.

2. Divide each of the difficulties to better examine and solve them.

3. Establish an order of thoughts, starting with the simplest objects to the most complex and diverse, and thus keep them all in order.

4. Review all things so you do not miss anything.

So, the chemistry of physics was separated from the chemistry of biology, the atom was separated from the molecule, the molecule from the cell, etc. The complex organization of the world and living things was thus separated or disjointed; in other words, each thing became an object of study, independent of its environment or context. Cartesianism (the interpretation and application of Descartes’ thought) has reached certain limits: by separating everything from its whole, we also cut off a part of reality. This reality that we have truncated can hardly be ignored when it comes to understanding phenomena that can not be reproduced or isolated in the laboratory without fundamentally changing the nature of the object being studied.

Simple thinking is a tool for mastering the real and not a tool for understanding the real. It isolates, divides, compartmentalizes and tries to provide a simple answer to all things and all phenomena. This approach seems so logical that we do not even question it anymore. Here are the principles of simplifying thinking as identified by Edgar Morin, what he calls the “paradigm of simplification”:

1. Disjunction means separating the studied thing from everything connected with it. One chooses the domain to which the thing corresponds, and one eliminates all the other fields from the study. For example, “I have a stomach ache” implies that the diagnosis will be established based solely on our knowledge of biology. Other disciplines and fields of knowledge are revoked.

2. Through reduction, from complex to simple, a hyper-specialization is formulated within the chosen discipline. What causes stomach pain can be related to the liver, the intestine, the stomach. One imagines an arbitrary division of the real, resulting in the apparent idea that there is a simple order to everything.

3. In abstraction, we abstractly unite causalities. Diversity is juxtaposed without conceiving unity (Edgar Morin, Introduction to Complex Thought, p.19). Stomach pain can be caused by overeating, or perhaps stress, or you have to pay attention to the liver.

Design and Complexity

From every point of view, design can become a complex practice. It is a transversal practice whose purpose is to intersect knowledge to reach a “humanly intelligent” resolution in a given context. It must now succeed in bringing together, linking and communicating different and sometimes even opposing disciplines and fields of knowledge. In short, can design work outside the subjective divisions of our knowledge and preconceptions? However, design practices used for commercial purposes rarely allow the mediation of complexity; instead they encourage an over-simplification of the world for consumption purposes.

Before going further, it is necessary to return to the definition of “complexity” and “complex thinking”. Edgar Morin defines it thus: “What is complex cannot be summed up in a master word; it cannot be reduced to a law; it cannot be reduced to a simple idea.” He continues: “It does not follow the ambition of the simple thought, which was to control the real. It is about exercising a thought capable of dealing with the real, to dialogue with it, to negotiate with it.” Therefore, design needs to situate its practice in a relationship of dialogue and negotiation with the real. In that sense, the humanities and social sciences are obvious allies which, despite their shortcomings and challenges, provide essential exploration methods. For example, the work of the anthropologist Philippe Descola proposes an ecology of relations that opens an alternative path to the classical dualism between nature and culture, which ultimately reveals a powerful anthropocentrism and Eurocentrism.

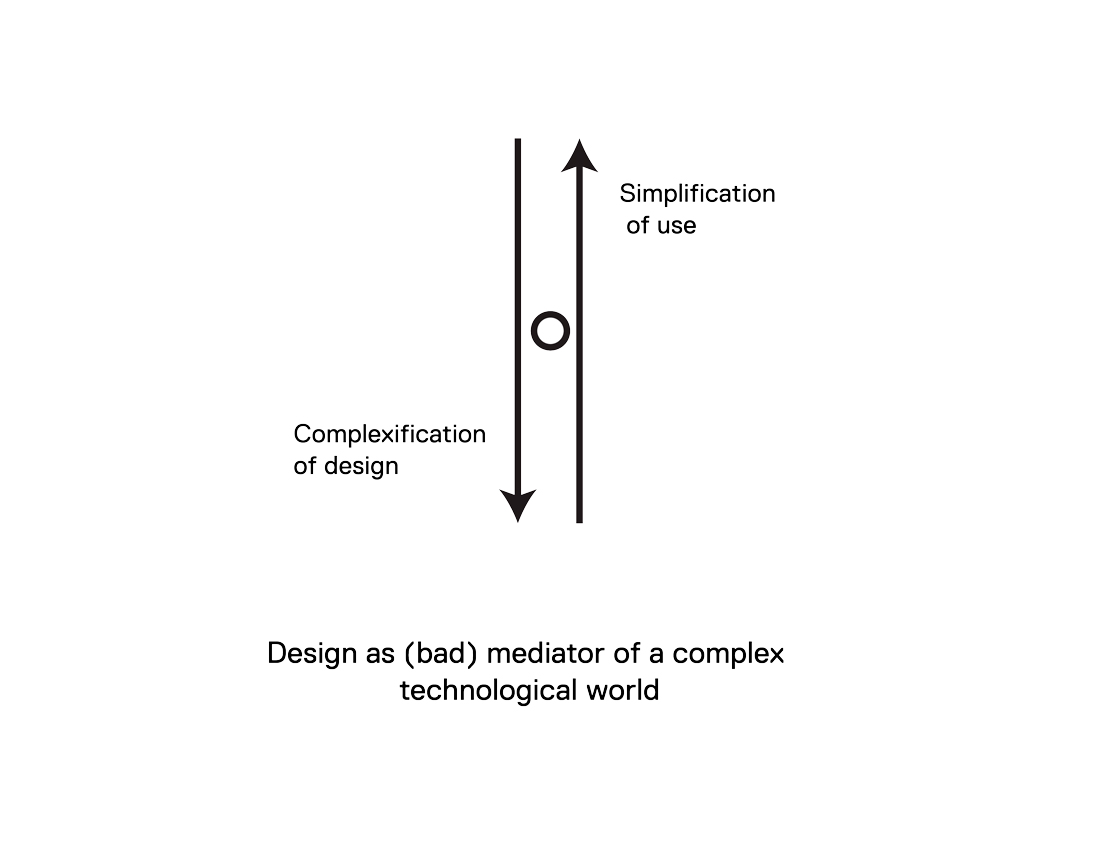

Having defined the terms and the stakes, I would like to dwell more on a phenomenon of design which seems to me notable in our societies – not because it is singular or new, but rather because its acceptance without any form of criticism seems to me dangerous. This asymmetrical phenomenon could be called “over-simplification by design” involving interactions with a world that is increasingly complex. This phenomenon describes the current of thought and the practice of the designer that aims simultaneously to simplify the interaction and the interface between the user (human) and his environment (world) – the same environment that becomes more complex because of the new techniques that modify it. In other words, as the techniques used become more and more complex (advanced electronics, new materials, programming including self-learning algorithms, etc.), the socio-economic structures become more and more complex to organize. And yet, the products and delivered services are always more simplified and minimalist. The question posed in this way is quite simple: Why are the interactions and interfaces of products and services designed by the designer aimed at simplification, whereas the technologies, which allow these same interactions and interfaces to exist are increasingly complex?

Intermediation and mediation sometimes lead to a simplification of what is medieval; in this regard, the phenomenon is not new. What it does is simplify the use of quantifiable complexity linked to rationalized technological designs and globalized practices. Human and social complexity cannot be included, because it is not rational and is even less quantifiable compared to technological complexity. We can therefore agree that any attempt to simplify interactions between humans and societies cannot really be effective, concrete or globalized. Similarly, it would be futile to ask designers to design products or services that could move symmetrically with human and social complexity, since that is probably unattainable with our current designs.

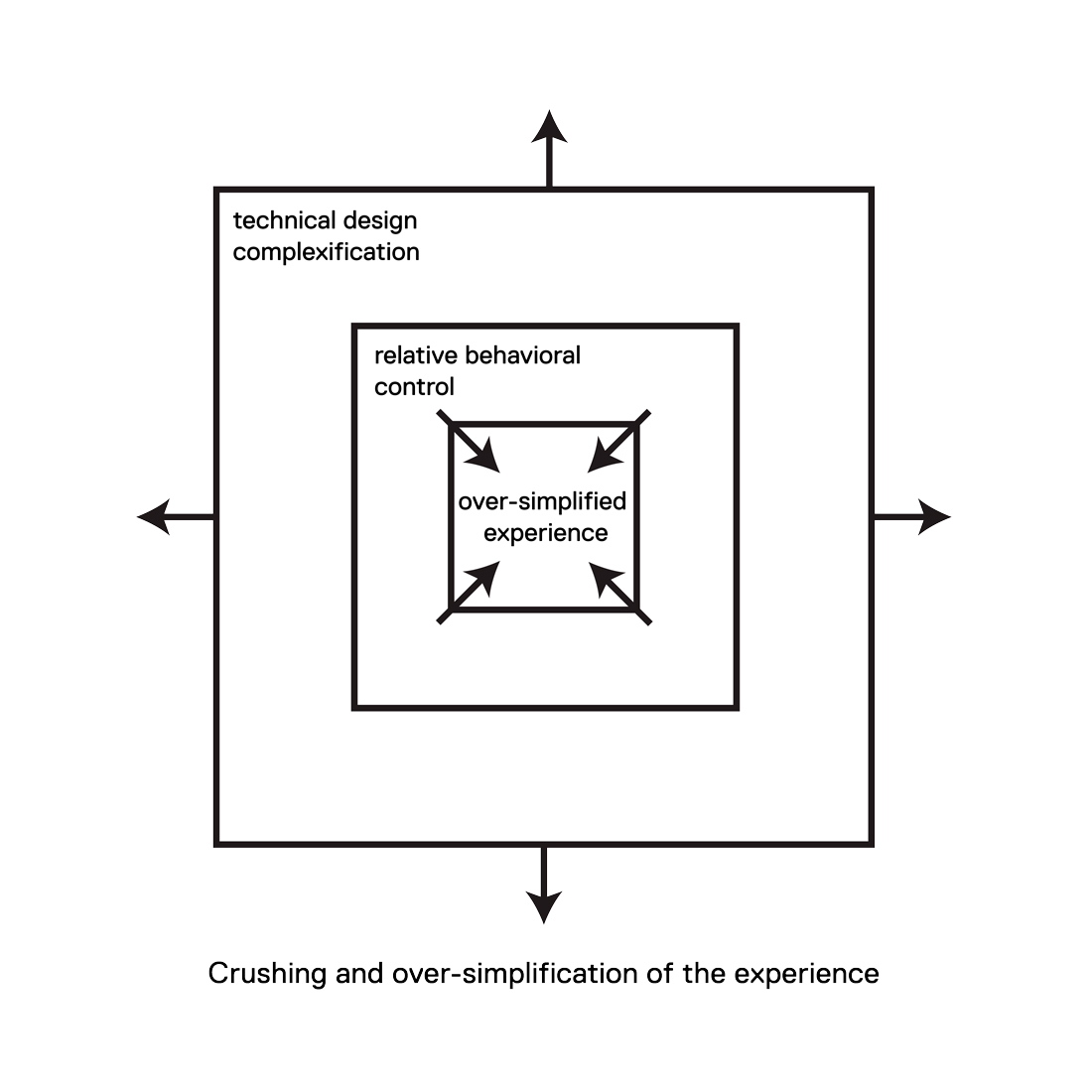

When we come back to technological complexity, which is quantifiable and rationalized, why are we not trying to advance its use in a similar dynamic? When browsing most of the teaching resources that are available to interface and interaction designers (UI and UX) the main goal is to create a frictionless experience, a “clear, flexible, familiar, efficient, consistent and structured interface”. This desire is commendable if we know why we do it. Why should the experience be clear and simple? Is it because the proposed experience is of little interest to the user and should take only a minimum of his time? That would seem to me like a decent reason. However, we now see mechanisms appear in interfaces and interactions (always simple and clear) that aim to maximize the time of the user spent on the service used. Here we see a second dynamic: as the technological complexity grows, the uses aim to become more and more simple, and a relative mastery of “human” complexity (behavioralism for example) is added to maximize the efficiency of the simplicity of use. This is a famous compressor, in which the user of the service is forced into an over-simplification by two complex dynamics.

What I mean exactly by “over-simplification” in this context is the dissolution of the essential elements of an experiment until it offers no reflective potential. In a way, it implies proposing an experiment that aims only to maximize a single result (outcome) rather than to seek a diversity of effects. This practice of oversimplification is what governs today the methods of design when it comes to creating services for the general public with a technological base. The maximization of the economic value of the uses is the only criterion that one seeks. We are therefore being asked to design clear, flexible, familiar, and effective sites for the sole purpose of maximizing the substantial economic benefit of their experience. In this respect, it is interesting to note that in France, for example, the most complicated or complex sites are those of public services whose economic value of use does not need to be maximized.

The Mediation of Complexity

In what way is oversimplification ultimately a matter of concern for me? The main failure of a simplification of use is the simplification of the world of the user. We can assume that the user’s response might be as follows: since it is easy to use then it is easy to do. His world and his presumed knowledge of that world narrows as he is faced with oversimplified experiences. Finally, when he finds himself confronted with complex experiences and problems, he is unable to accept their ability to be solved by complex means, of which he is ignorant. Here we find the disjunctive dynamics of the simplifying thought mentioned above.

Of course, it is not a question of understanding all the techniques used when using a service; it is merely a matter of being aware of the complexity inherent in the use of the service. That is why design must play its role of mediator. Because a complex experience engage social bonds, emotional ties, economic ties, it is ultimately an experience through which one learns about oneself and the world, without necessarily being willing. As such, design mediation should aim to reduce oversimplification by revealing complexity, not hiding it, and creating a framework for accepting the complexity of the world.

It seems to me that a complex un-designed world prevents any attempt at projection in the future and thus condemns the present. To accept complexity and its paradoxes is, in a way, to reconquer the idea of the future.