New Conditions, Old Solutions

Cities today are being made and re-made at a faster pace and at a larger scale than ever before. Since its inception, the Urban Age project has captured the varied dynamics of these changes. The diverse voices in this book give some texture to the impacts of such changes on people, places and the environment in cities across the globe. Yet, despite the increasing complexity and specificity of the urban condition, there is a generic uniformity in the spatial, architectural and planning realities that are being built on the ground. This essay explores the origins of these models, offers a critique of their rigidity and lack of complexity, and sketches an outline for a more incremental, flexible urbanism that engages with the indeterminacy of urban change.

Regularly spaced high-rise towers, separated by dead space and wide roads, divided into rigid functional zones – Central Business Districts, industrial zones, retail and leisure parks, government districts, residential quarters – define many of the emerging landscapes of new or existing cities. Songdo in South Korea, Gurgaon in India and Kigali in Rwanda possess many of these characteristics, as do the dormitory towns on the edges of Istanbul, Mexico City and Kuala Lumpur. Even the centrally planned metropolitan uber-region of Jing-Jin-Ji – 120 million people around Beijing – borrows from a visual, spatial and functional language that has become familiar, even commonplace.

So where do these ideas come from, and why do they matter? Their origin goes back to an ideological and spatial model that is at least 80 years old. Outside the architectural profession, the Charter of Athens is a relatively obscure document. Conceived in 1933 on the SS Patris cruise liner en route to Athens, by the Congress Internationaux d’Architecture Moderne (CIAM) – an elite group of predominantly Western male Modernist architects and planners who met regularly between 1928 and 1959 – the Charter is a manifesto for the functional city. Strongly influenced by Le Corbusier’s earlier treatise on the Radiant City and his proposals for the Plan Voisin in Paris, its 94 recommendations were not published in English until the end of World War II in 1946.[1]

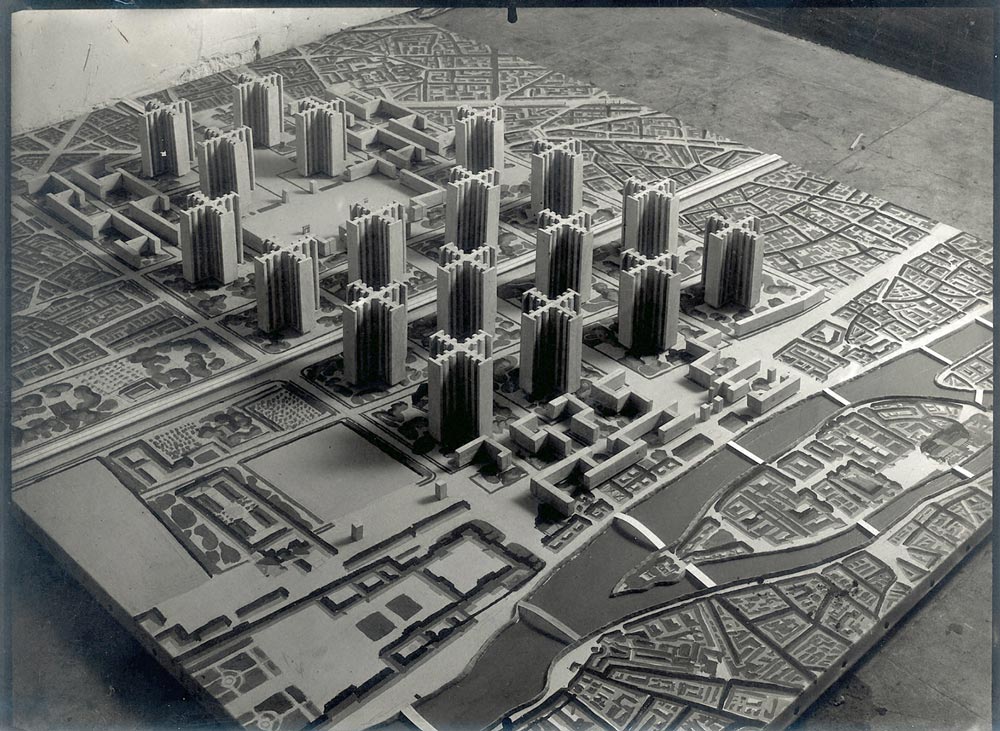

Plan Voisin, Paris, France, 1925

Le Corbusier’s technocratic vision of equally spaced towers that benefit from daylight and fresh air, clear zoning of functions and the separation of cars and pedestrians, has had a pervasive impact on the language and form of late twentieth- and early twenty-first century cities.

The Plan Voisin was designed ‘to save the industrial city from disaster’.[2] Like other major cities in Europe and the United States, Paris had grown into an overcrowded megalopolis. Its peak density in 1861 was similar to some of Shanghai’s inner-city districts today. The speed and scale of the nineteenth-century wave of urbanization was less pronounced than the one we are witnessing in the early twenty-first century. The expanding industrial centres of London, Liverpool, Glasgow, Chicago and New York concentrated the new urban working class into poorly serviced neighbourhoods where entire families lived in one room, child labour was common, life expectancy among young men was well below the age of 30 and belching coal fires poisoned the atmosphere. Different times, location and scale, but not dissimilar environmental and human conditions to the slums of Mumbai, Nairobi or Jakarta today.

By the 1920s, inner-city neighbourhoods such as the Marais in Paris had become congested and ridden with disease. Public health was a major concern. The emerging generation of architects and planners responded with radical new solutions inspired by the Machine Age: mass electrification, the motor car, industrialized construction and the elevator. Le Corbusier’s vision made the most of new technologies in order to improve the quality of life of city inhabitants. He replaced a large section of dense, pre-industrial city blocks with a gridded phalanx of 18 cruciform towers, equally spaced in a vast green urban field. Fresh air could circulate through the open windows. Each inhabitant had a view and access to daylight. Cars and pedestrians circulated efficiently at different levels, freeing up the ground plane for fast-moving traffic. People would live in peaceful, well-lit, modern apartments away from the noise and smells of industry and heavy traffic.

While Le Corbusier famously called for the ‘death’ of the dark, unhealthy two-sided corridor street that epitomized the shortcomings of the pre-industrial city,[3] the Charter went much further. ‘Chaos has entered into the cities’, it declaimed, but it could be tamed. By deploying a set of technical instruments and imposing strict planning laws, the new, regulated, efficient urban order would lead to healthier, more efficient and productive urban systems. This message appeals as much today as it did to the planners and policy makers of the mid-twentieth century.

Ideology and Form

The Charter was written in an accessible, manifesto-like style. Its technocratic paradigm was clear and unambiguous. It argued that the ‘four keys to urban planning are the four functions of the city: dwelling, work, recreation [and] transportation’ and that all new cities should be zoned accordingly, removing at one stroke the complex layering of multiple activities that define urban life and transactions. In stipulating that ‘high-rise apartments [be] placed at wide distances apart [to] liberate the ground for large open spaces’, it eliminated the street and all the associated human interactions that support trade and social cohesion and give a sense of connection. To be properly modern, the Charter recommended, ‘roads should be differentiated according to their functions: residential streets, promenades, through roads, major highways’ and ‘heavily used traffic junctions should be designed for continuous passage of vehicles, using different levels’, prioritizing the needs of fast-moving vehicles over the human individual. Despite their collective belief in social progress and improvement, the authors of the Charter were unambiguous in their attitude towards concentrated poverty: ‘unsanitary slums should be demolished and replaced by open space’.

Taken as a whole, the Charter’s 94 recommendations add up to a synchronous vision of the city, where form equates neatly with function, where social problems can be resolved with technical solutions, where people living in cramped and overcrowded conditions – devoid of basic services – are (willingly or unwillingly) accommodated in decent conditions with running water and electricity supply. It is an attractive, easily digestible and optimistic vision of the efficient city, devoid of its messy contradictions and open to the future. But cities are not machines. They are the products of human society: indeterminate, unpredictable and fragile.

It is the one-dimensional certainty of this approach, its ‘solution-oriented’ formula, applicable everywhere, at any time, which appealed then and appeals now to urban leaders, investors and planners. It is much easier for a mayor to redesignate agricultural land as a business park or housing project, say, than to retrofit new functions into existing, built-up areas with established ownership patterns and vested interests. It is technically less cumbersome to lay electricity cables and sewers in virgin fields even though they may be remote and inaccessible from jobs, schools, hospitals and shops. It is more convenient for contractors to place their ‘cookie-cutter’ designs for apartments and offices in locations that are not constrained by existing legislation, rights-of-light, density restrictions and NIMBY interests.

Nearly a century has passed, but the Charter’s spatial prescriptions define much of the built reality of contemporary cities. Istanbul and São Paulo are still building dormitory towns on the periphery; many Indian cities encourage out-of-town shopping centres, business parks and call centres; flashy new CBDs are imagined for New Cairo, Kigali and the new towns of Kazakhstan and Vietnam. And Mexico City and Mumbai are still building flyovers to connect new monofunctional districts. Despite the significant investment made in China and South Korea in housing and public transport infrastructure, the character of hyper-dense residential districts remains disconnected, anonymous and devoid of everyday urban life. In addition to their functional separation, many of these projects are designed as enclaves, closed urban systems incapable of incremental change, inflexible building types bounded by lifeless public spaces.

A by-product of this functional reduction has been the erosion of the public realm. As a consequence, the potential for everyday transactions and unplanned encounter has diminished, often sucking the essence out of city life and deadening everyday urban experience. The strict separation of functions, prioritization of the car and elimination of the indeterminate and unexpected has resulted in a generic urban genre which indeed imposes a degree of order, but an inflexible and brittle one that reduces the level of complexity and negates the very sense of urbanity and the potential for cityness.[4]

While the Charter ends with the exhortation that ‘private interests should be subordinated to the interests of the community’,[5] its application has encouraged land speculation and increasing ghettoization. For example, the oversized 1980s office complex of Canary Wharf in East London was conceived as a zoned enclave that provides jobs but is severely cut off from its surrounding communities. Puerto Madero in Buenos Aires follows the same exclusionary spatial principles, while Rio de Janeiro’s Olympic ‘legacy’ project is ending up as a segregated development (concealed behind walls) rather than an open, connected, mixed piece of city.

Many of these typological interventions, especially those in rapidly urbanizing regions of the world, result directly from planning legislation rooted in Charter of Athens ideology. Zoning regulations, which determine the quantum and type of development, actively promote the designation of segregated industrial zones, education zones, leisure zones, commercial zones and tax-free zones alongside the ubiquitous Central Business Districts, residential quarters and shopping centres. Entire urban districts in or around Kuala Lumpur, Jakarta, New Delhi and São Paulo are planned in discrete functional sectors, often separated by wide freeways, heroically scaled traffic roundabouts and large expanses of surface car parking. While new residential suburbs of Shanghai, Shenzhen and Guangzhou provide modern accommodation for the emerging Chinese middle class, the wide spacing of repetitive towers creates a lack of active edges along oversized roads, and their lifeless daytime character is determined by municipal regulations hatched in the post-World War II era.

Shanghai, China

Like many new districts in rapidly urbanizing regions of the world, this development in Shanghai adopts a ubiquitous tower typology that neutralizes the relationship between the buildings and the ground and divides the city into distinct functional clusters surrounded by impermeable freeways.

Reframing the Urban Debate

The conditions and the forces that shape the urban environment have changed dramatically since the mid-twentieth century. The exponential rise in urbanization and globalization, the steep rise in migration and informal growth, the transformative effects of new information technologies, the impact on climate change and awareness of resource scarcity, and the profound increase in inequality have impacted the dynamics of urban growth. In the face of such a complex, interconnected set of causes and effects, a reductionist paradigm appeals to anyone concerned with ‘getting things done’. In this ideology, cities are seen as ‘problems’ that have to be ‘solved’, rather than fragile metabolisms that need to be shaped, steered and nurtured. It is the paradigm and not just the solutions that need to be reframed.

Time is critical to urban growth. It takes generations to build up the spatial, social and cultural depth and richness that make cities attract flows of people, goods, money and ideas. Equally important is the ability of a city’s built fabric to adapt and absorb urban churn. Since its conception in 1811, New York’s Manhattan grid and building typology has sustained a variety of activities, from industrial warehouses to housing projects, artists’ studios, bankers’ lofts and fashion houses. The transformation of the city’s waterfront owes as much to the resilient design of the building stock and urban form as it does to Mayor Bloomberg’s rezoning policies.[6] The commercial and popular success of the High Line relies on a relatively simple intervention of retrofitting a disused railway line. The democratizing effect of Manhattan’s street layout has been instrumental in increasing the city’s capacity to react to radical shocks to its economic, social and structural systems over a period of time. Yet, despite the challenges of gentrification and the exorbitant cost of real estate, New York is not divided up into inaccessible gated communities. It remains, spatially, an open city.

Barcelona’s famous diagonal grid with chamfered corners, implemented by Ildefons Cerdà in the mid- to late 1800s, has also stood the test of time. Developed by an engineer to support the city’s expansion and to house the emerging middle class, the urban structure has become intensified and enriched over the last two centuries, but the basic streetscape has remained the same, endlessly adaptable to change. At the time of writing, the city’s mayor is exploring ways of transforming sets of nine Cerdà blocks in central Barcelona – three blocks by three blocks – into car-free zones, adapting the nineteenth-century city conceived for horses and carts into a contemporary model of urbanism that reduces car traffic and pollution, and maximizes sociability.

Kings Cross, London, United Kingdom

The tensions between public and private interests will continue to dominate the evolution of cities in the developed and developing world. Managing the interface through enlightened stewardship and design vision can, as in the case of the King’s Cross development in London, provide an incremental and flexible model on how to shape cities and the lives of their citizens in the next decades of the twenty first century.

London has followed a similar process of metabolic adaptation over time, but from a different starting point. The world’s first megalopolis was never planned. It grew organically from its ancient Roman core, first connecting rural villages and then absorbing the great estates of aristocratic landlords in the Georgian period before reaching over 8 million people by the start of World War II. Behind London’s urban ‘disorder’ lies a spatial structure that bends and bows in response to a very British cocktail of market pressures, collective ambition and sense of justice. So much so, that some of the Mayor of London’s planning policies[7] have been described as ‘catch and steer’: a design approach that maps and values existing urban assets (pubs, housing estates, rivers, canal walkways, disused industrial structures) as the starting point of a collage-based approach to urban retrofitting championed by emerging design practices such as Assemble, Witherford Watson Mann and East architects.[8] At the same time, though, London has been the subject of heavy-handed interventions, fuelled in part by overseas capital, that have literally disfigured the scale and character of some its more fragile urban communities extending from the Isle of Dogs to the bulging riverfront along the south bank of the River Thames.

In this context, the ongoing redevelopment of a large area of East London – galvanized by the 2012 Olympic Games – offers a more malleable approach to master planning, in effect an ‘anti-Charter’ model.[9] Driven by the political ambition to cure one of the city’s most enduring spatial inequalities – the deep imbalance between London’s relatively affluent West and deprived East – the vision for the project was framed in a long time horizon (25 to 30 years) with an open, flexible plan that could – and should – adapt to different uses and building forms as circumstances changed and evolved. From the outset, this US$10 billion publicly funded project was designed to be incremental, not a static piece of rigid urbanism where, as in the Charter, form equates neatly with function.

With more than 35 new links – bridges, cycleways, pedestrian routes and canal towpaths – the former railway goods yard, which had for decades been cut off from the city, has been grafted back into the fabric of East London. The new piece of city – like much of London – is intentionally not divided into separate functional zones. Today, it is possible to walk, cycle or drive across an extensive part of the city that historically turned its back on its surroundings. Only a few of the Olympic sports venues were kept – the Aquatics Centre, the velodrome and the main stadium – and repurposed for community and non-Olympic events. The cavernous Media Centre complex, which would typically be abandoned when the Olympic circus leaves town, was transformed into a tech employment cluster offering several thousand new jobs, many available to local residents. All other sports venues were designed as temporary structures, sold and removed to other locations or recycled after the games ended, avoiding wastage of money, materials and land.

Retrofitting was a driver at many scales across the project. Oversized pedestrian bridges designed to carry hundreds of thousands of visitors during the few weeks of the Olympics were constructed to be dismantled, reduced to an urbanistically more friendly scale for the new inhabitants of the area. The Athletes’ Village was converted into affordable and private rent units that now provide homes to more than 10,000 people in a part of London that lacks housing. The terraced houses and courtyard apartment blocks have been arranged along streets and dispersed into different clusters – not concentrated in a single residential zone of uniform towers – mirroring the organic nature of London’s urban DNA.

More than 50,000 people will eventually live in the wider site by the time the development is complete, in around 2030. Each neighbourhood has – or will have – a local school and new health and community facilities as well as access to London’s first new park in more than century. To confirm the resilient and flexible nature of the plan, an attractive canal-side area initially designated for commercial offices has been reconfigured as an arts quarter, bringing universities, museums and performance spaces to an unloved corner of East London – a development that would have seemed inconceivable a decade before the 2012 games.

The Olympics legacy in London is a project in progress, still open-ended. This may be one of its strengths. But, the project has its strong critics.[10] Gentrification and increased land values have clearly had an impact and, despite favourable numbers, the debate around who has gained in terms of employment, health and well-being still rages on.[11] From a planning perspective it constitutes a marked shift in the paradigm of city making. It is an example of planning by accretion rather than rupture, providing a framework for growth without being overly prescriptive, building on London’s Londonness just as the Manhattan grid and Cerdà’s Eixample interpreted and shaped the dynamics of change in New York and Barcelona for many generations.

These examples are matched by initiatives in cities across the world. In Europe, the extension of Hamburg into the disused harbour on the River Elbe has given rise to the new neighbourhood of HafenCity, where a mix of building uses – residential, cultural and commercial – opens out on to traditional streets and well-designed public spaces. The Orestaden quarter in Copenhagen is bringing high-density and varied development to a peripheral area now well served by public transport. Both projects are founded on relatively open master plans, where building types, uses and densities are not predetermined but revised and modified according to shifting economic, social and environmental realities. Building on the positive experience of many Latin American cities since the late 1990s, the recent Reinventer Paris initiative is an imaginative exercise in urban acupuncture where individual projects – a migrant hostel, craft workshops, sheltered housing and public spaces – are placed in strategic locations to address the French capital’s enduring social divide between the affluent central core and the more deprived periphery.[12]

The authors of the brave new world of the Charter of Athens would have found these projects unimaginable. The lack of an all-embracing, form making, transformative modern vision, where the old is swept away to make way for the new, would have been seen as a sign of weakness on the part of city leaders to grasp the once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to implement lasting change. In effect, they needn’t have worried. The more subtle, flexible examples of urban intervention still make up a small percentage of what is actually built. The one-size-fits-all model is still dominant, providing simple solutions to the pressures of urban growth and churn.

Designers, developers, investors and policy makers are faced with increasingly tough choices as to how to intervene in changing urban physical and social landscapes. How do you maintain the DNA of the city when it undergoes profound transformations? Who is the city for? How do you reconcile public and private interests? Who pays and who gains? The city planners of London, Paris, Barcelona, Hamburg and New York are grappling with the same questions as the urban leaders of African, Latin American and Asian cities, even though the levels of deprivation and requirements for social infrastructure may be of a different order of magnitude. Yet, the design and planning solutions – often imported via international professional offices and consultants – offer remarkably similar solutions whose roots can be traced back to the mid-twentieth century.

Since 2005, the Urban Age project has provided a specific lens on the way cities are changing, focusing on the interactions between the physical and the social. Through this perspective, the process of urbanization appears incomplete, messy and organic. None the less, many solutions implemented on the ground are prescriptive, finite and rigid. To address this imbalance, there is an emerging consensus among urbanists for the need to re-examine and reframe the assumptions that underpin planning practices worldwide. The strict functionalist separation of activities should be questioned in favour of clustering multiple activities at higher densities in well-connected places. Formal solutions that promote segregation and isolation should be revisited in favour of more elastic environments that tolerate heterogeneity and accept change. City making should embrace a broader time frame, with an openness to the past and the anticipation of an uncertain future.

Ultimately, the Urban Age project recognizes that urbanization is a necessarily open process that is both iterative and incomplete. The understanding of current urban practices suggests that we need to move away from the rigidity of the technocratic, generic Modernist model inherited from the Charter of Athens, towards a more open, malleable and incremental urbanism that recognizes the role of design, time and space in making cities more liveable.