Today, urban environments face ever-increasing flows of human movement as well as an accelerated frequency of natural disasters and iterative economic crises that dictate the allocation of capital toward the physical components of cities. As a consequence, urban settings are required to be more flexible in order to be better prepared to respond to, organize, and resist external and internal pressures. At a time in which uncertainty is the new norm, urban attributes like reversibility and openness appear to be critical to a more sustainable form of urban development. Therefore, in contemporary urbanism around the world, it is clear that in order for cities to be sustainable, they need to resemble and facilitate active fluxes in motion, rather than be limited by static, material configurations.

Temporary cities have a lot to offer in the study and application of contemporary urbanism. However, given their heterogeneous nature, it is difficult to organize a cohesive terrain of scholarship from which to springboard into mainstream application. For this reason, Andrea Branzi’s prototypes form the first alternative and taxonomic hypotheses oriented to these new configurations, as alternative to the stable cities, and a crucial scientific platform on which to incorporate theoretical work into the rethinking of the urban structure. In this parallelism between theory and phenomena lies the conjunction of our research areas.

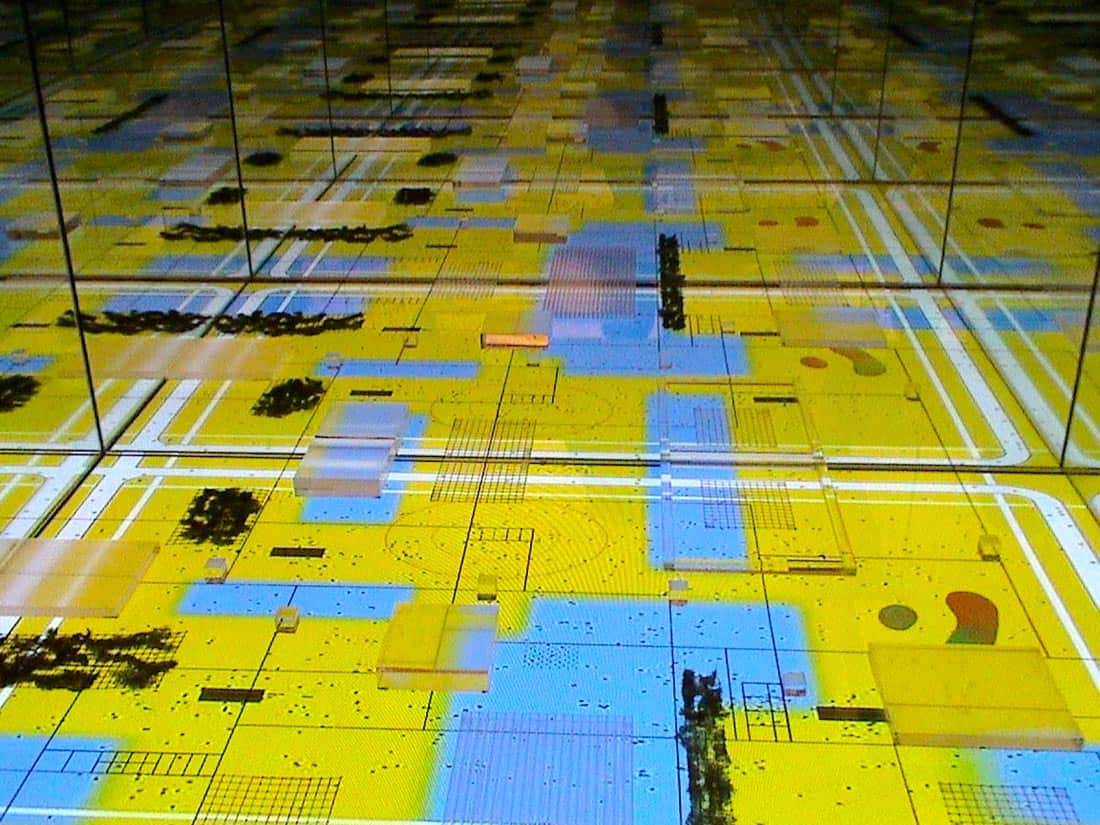

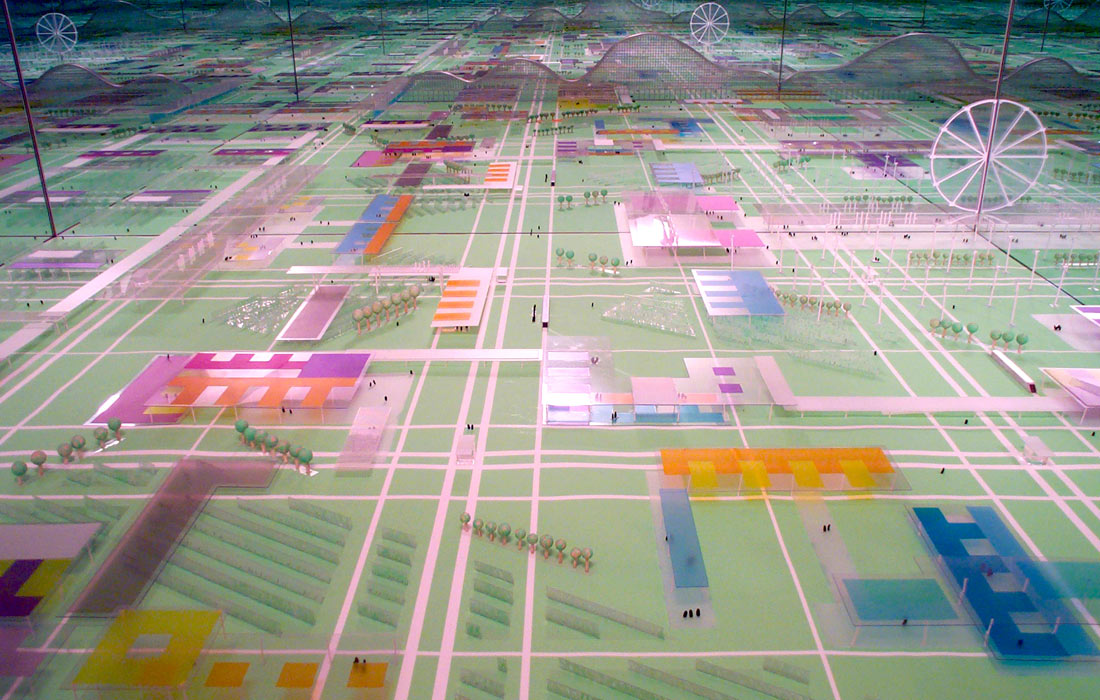

As the contemporary temporary cities, Branzi’s weak urbanization models, and his new principle of universal and reversible urbanism, unlike more permanent ones that have a range of elements that simultaneously support their continuity, are usually structured around one main purpose. This modus operandi is not only the central force that defines an ephemeral city’s dimensions and complexity, but also the life cycle of the settlement, its material composition, and its place in the cultural memory of its society. Following this line of thought, it is possible to categorize ephemeral cities in clusters of cases configured in diverse taxonomies, as Branzi’s definition of a new glossary for urbanization, taxonomies fused by their common characteristics of ephemerality and temporariness.

In their concrete phenomenology, these varied taxonomies could be a useful way to organize cases that are differentiated through variables such as length, size, metabolism, generated levels of risk, patterns of spatial use, grid morphology and complexity, technology, logistical implementation, et cetera. They respond to particular conditions and contexts while sharing the certainty—or at least the expectation—of a date of expiration. Thus, they challenge us to develop tools for intervening and thinking about impermanent configurations as a legitimate and productive category within the discourse on urbanism. In fact, they represent an entire surrogate urban ecology that grows and disappears on an often extremely tight temporal scale. When temporary urban landscapes are seen as the expression of a distinctive form of urbanism, then a potentially productive dialogue is established between ephemeral settlements. These settlements span a diverse range, from refugee camps to weekend-long festivals, along with other temporary urbanizations meant for celebration.

Andrea Branzi’s ten recommendations for the construction of a New Athens Charter offered critical provocations for the radical rethinking of the urban as a more inclusive and less Eurocentric project. Of his ten recommendations, the third seems to point directly to the construction of a new concept of time in a city that should be thought of as a place for “cosmic hospitality” in which designers could encourage “planetary coexistence” between “man and animals, technology and divinities, living and dead.” In doing so, a model for the city could be found that is “less anthropocentric and more open to biodiversity, to the sacred, and to human beauty.”[1]

Religion as a taxonomy of ephemeral urbanism—as Branzi’s expresses it in his texts and project on new Fundamentalisms—seems to advance this line of thinking, reactivating the contents forgotten by the Modern Movement, and proposing temporary reconfigurations of the urban that are, in a way, short glimpses of this very city model. In this sense, ephemeral landscapes of religion are constituted by cases in which the urban space is modified, totally transformed, or even created in order to facilitate the practice of faith. These cases present thoughtful strategies for ephemeral configurations deployed to celebrate religious beliefs. Some of the cases, such as the Qoyllur Rit’i in Peru, go so far as to generate temporary megacities from almost nothing. Others convert streets into open temples, such as the light constructions made annually to host the Durga Puja in Kolkata, while others transform massive regional infrastructures into a procession path, as in Lo Vásquez, Chile, to demonstrate an alternative urbe of the stable stateof the city.

As deeply expressed in his Models of Weak Urbanization and in his most recent research, the ephemeral city is often constructed out of light materials, which allows it to adapt to a range of contexts, to be transported, and to colonize all sorts of spatial conditions. In many cases, an ephemeral city is constructed outside urban centers, as in the case of Burning Man, which is assembled in the middle of the Nevada desert. In the Qoyllur Rit’i (translated as the “Snow Star Festival”) in Peru, an ephemeral settlement is deployed in the once vacant valley near Mahuayani. For this religious celebration, devotees travel the steep cliffs and long trails of the Andes. People come from all over the region to gather once a year at the shrine of Qoyllur Rit’i to sing, dance, and wear traditional costumes. What makes the Qoyllur Rit’i unique is that it is one of the most physically enduring religious events in the region. It requires participants to carry tents, material for stages, instruments, and other festival gear with them during their journey up the mountain to pay respect to the shrine perched precariously at a great altitude. Given the walking nature of the pilgrimage, all the goods used to assemble the ephemeral city are extremely light. Plastic, fabric, and light, portable structures are used in the construction of the city. The lightweight image of the settlement is juxtaposed with the aggressive and heavy presence of the rock-faced mountains.

In the same way that religious ephemeral settlements are a means for what a society perceives as valuable and memorable, other ephemeral forms play similar but secular roles. Temporal celebratory landscapes are also ways to provide space and place for the conservation of social traditions, enhancing the values of cohesion and allowing for interactions in the form of cathartic gatherings. In this way, in addition to ephemeral settlements fostering the encounter with the sacred, many other impermanent landscapes appear for the support of the celebration of the mundane, inside and outside the city. Sacred ephemeral landscapes open opportunities for inverting hierarchies and making horizontal social relationships in the city. They also transform thresholds, softening them. Both things are achieved by the implantation of a major common purpose that unifies differences.

Celebratory ephemeral manifestations achieve the same effect, as they provide heterotopic spaces in which one can usually see the dissolution of social predetermination and a diversity that is not normally achieved in the everyday city. Nonreligious cultural celebrations have historically been places of social intensity and cultural expression. Many settlements regularly pop up around the globe, creating “contact zones” for groups of people that would otherwise not interact with or even find each other. These structures are well expressed in the softer, secondary layers that penetrate the permanent city, as in the case of Latin American carnivals and street parties or the massive artistic performances that activate urban spaces, or even in the form of discrete settlements outside or adjacent to urban centers all around the world. The increasing scale and frequency of subtle settlements is causing the expansion of more and more erected structures within and outside of urban areas. Music festivals, such as Exit in Serbia, Coachella in California, and Sziget in Budapest, motivate the construction of extended ephemeral settlements that for short periods of time congregate large groups of people. They range from relatively small gatherings, like Burning Man in Nevada or Fuji Rock in Japan, which attract around 40,000 people, to events like Glastonbury in England, the Roskilde Festival in Denmark, and Rock Werchter in Belgium, which draw in around 350,000 people.

As we have seen, temporary celebratory landscapes are disruptions to the “business as usual” condition of the city. They open the way for very intense, short-term interactions that physically transform the urban space, allowing for cultural expression in perhaps its most radical condition. In these contexts, the individual and the community are placed at the center through great strategies for social and spatial bonding. The permanent city becomes secondary to the idea of a shared cultural connectivity.

There are other forms of the temporal in which architecture and urban design work in completely opposite ways to that of ephemeral cities of celebration. This is a neutralizing urbanism that disposes of grids and units, as well as any expression of identity, reducing life to its more basic and “bare” condition.

The refugee camp[2] would offer an exact exemplification, as the new emergent city following natural calamities. As Agamben said: “Today, it is not the city but rather the camp” that is “the fundamental bio-political paradigm of the West.”[3]

Often representing the overturning of ephemeral cities, since they are transformed from temporary encampments to real consolidated cities, camps connect directly to another prototype, one that is linked to military needs, through the construction of removable and temporary infrastructures.

As Branzi pointed out through the idea of reversible urbanism and weak infrastructures, military settlements seem to offer an exact example, closer to the dynamics and structures of the cities destroyed because of natural disasters.

Also the global problems provide an expression of the ephemeral city on the rise. Changes in climatic conditions are increasingly making evident the importance of temporary shelters as holding strategies or short-term solutions. In the Philippines, Haiti, Chile, and several other afflicted nations, temporary cities are built in the context of disaster.

Today, the planet is facing unprecedented uncertainty, as climate change is rendering once stable areas of the planet vulnerable. The ecological uncertainty and the growing challenges tied to climate change bring notions of space, occupation, and public health to the forefront. Moreover, social inequality unveils urban and rural settlements as we are pushed to seek alternative methods for dealing with the current conditions. These landscapes of disaster create camps all over the globe.

Or, mentioning another term of our glossary, the ephemeral city is shaped where there are some natural resources.

In these cases, the life cycle of temporary cities aligns with the duration of the extractive activity and the presence of the resource. Therefore, most of these settlements are developed knowing that they have a predictable expiration date.

In the ephemeral landscapes of extraction, the structure of the camp, rather than a biopolitical management artifact, often becomes a productive engine for the profitable management of the territory, subjugating every aspect of life to that purpose. This is a form of urbanism at the service of global economic flows, which determine the patterns of growth in relation to the demand for commodities based on access to natural resources. In this sense, ephemeral landscapes of extraction are a by-product of the extractive activity that, being local in its operation, is determined by global needs and aspirations. They emerge as highly efficient systems that maximize productivity, optimize processes, and produce automated and standardized results. It is the perfect embodiment of the paradigm behind every extraction activity: efficiency. Indeed, it is efficiency that drives the layout of the site, the organization of logistics, the spatial configuration, and the processing of the resources once they are extracted. It is the same efficiency that constructs the conditions for bare life to be predominant, for “action” to retreat as secondary human activity.

David Harvey’s continuation of C. Wright Mills’s notions of sociological imagination coalesce with Louis Wirth’s ideas of urbanism as a way of life in order to provide contexts of extraction that act in the service of efficiency. They are therefore “deprived” of their “cityness” in order to fulfill their main purpose of accommodating people for a limited period of time, providing minimum levels of comfort and human interaction.

Conceptually speaking, in ephemeral landscapes of extraction the structure of the camp is recognizable not only in those that are set up explicitly as encampments but also in other layers of the urban—as the camp is the thinnest expression of a settlement. Such thinness is not only material, but it also impacts the social and political aspects of the camp, creating a constant tension between both paradigms of space production. On the one hand, referring to its material conditions, the camp operates in a similarly fluid way to that of the city. Despite its seemingly fragile appearance, it incorporates systems embedded with a great degree of elasticity and flexibility, which are able to adapt to transformations within the environment. Like other ephemeral settlements, the extractive camp has the capacity to be constructed within a short period of time. It can also be deconstructed at the same speed, simply by inverting the construction process.

As well expressed with great power of anticipation, Branzi’s prototypes of weak urbanization, the mentioned cases make us think about urbanism is a nuanced way. The city clearly needs to find alternative ways to give space to a more pluralistic economy, allowing flexible functional occupations to generate micro-operations that activate the urban landscape. Referring to this, Martha Chen advocates, “What is needed, most fundamentally, is a new economic paradigm: a model of a hybrid economy that embraces the traditional and the modern, the small scale and the big scale, the informal and the formal. What is needed is an economic model that allows the smallest units and the least powerful workers to operate alongside the largest units and most powerful economic players.”[4] In this way, acknowledging the contributions made by the range of different cases included in this book might help us to find the agency of urban design and planning in the design of such conditions.