At this year’s Venice Architecture Biennale, entitled ‘Reporting from the Front’, that focused on ‘humanitarian architecture’, Sir Norman Foster presented a ‘Drone-port’ for Rwanda. Speaking about the project, Fosters eluded that the drone-port emerged from the practice’s canon of airport architecture, but likened less to a building rather as ‘social infrastructure’. This will be the worlds’ first drone port with Foster’s architectural design complimenting the Jonathan Ledgard’s think-tank Redline Afrotech-EPFL, focusing on the application of advanced technologies in and across Africa. The drone-port intends to service difficult to reach hospitals with medical supplies across rurally remote parts of Rwanda.

Vision City, Gasibo, Kigali 2016

Foster’s drone-port is a simple array of structural arches that are formed out of compressed earth-cement ‘Durabric’ tiles. Tiles that prioritise local soil over cement reducing construction costs, where materials imported into Rwanda have increased transportation and a carbon footprint. In fact Fosters suggests that the drone-ports can cost less than the construction of petrol station. Stability is given to the tiles through the hand-machine presses, omitting the need for stability from the wood-firing processes that contributes to deforestation. The elegant catenary vaulted form constructed from earthen tiles laid and bonded over a pre-fabricated formwork that can be quickly assembled onsite. The construction technology builds historically upon the work of Rafael Guastavino, Antonio Gaudi and Eladio Dieste and is redolent of recent work by Peter Rich in South Africa and Light Earth designs in Rwanda, marking a renewed interest in structural vaulting as ‘appropriate technology’ within a recent ‘social architecture’ across Africa.

The drone port follows a number of western-based architectural practices behind MASS Design, Sharon Davis and Architecture for Humanity amongst others who have designed and completed buildings in Rwanda – a number of other African-British notables such as David Adjaye have designs pending. Social architecture has contributed significantly to the positive narratives surrounding Rwanda’s post-war physical and social reconstruction. ‘Development’ in Rwanda is an all-embracing process captured by the government’s integrated development plan called ‘Vision 2020 Umurenge Programme’. National unity and a desire for a globalised economy are at the root of much of the intentions behind President Paul Kagame’s vision that intends to reduce poverty through rural growth and social protection. This vision is indeed a supported one in the universal sense that it is the logical antecedent to the 1994 Genocide. Yet it is not entirely clear as to how democratic this vision is and who will benefit as scholars such as Andrea Purdekova suggest that fear, suspicion and distrust are internally rife within the political system as compounded by the Genoicde (Purdekova 2011). Rwanda’s power-struggles rarely play out in the public sphere with international human rights groups suggesting fear is capitalized upon as a regime to maintain administrative control towards this vision.

So how does this drone-project, advocating for technology usually with negative connatations, contextually sit within the political context of Rwanda’s heavily governed and monitored view of development?

Rwanda Social Security Board Buildings, inner city Kigali, 2016. Identical towers stand on land expropriated from low-income community of ‘Poor Kiyovu’ between 2008-2010

Rwanda is the smallest most densely populated country in sub-saharan Africa, with land shortages presenting a massive challenge for food supply, industry and infrastructure. Collective claims to territory are inseparable from the history of conflict across the Great Lakes region. The extent of which has played out since pre-colonial times with the entrenchment of ethnic territories under Belgian colonial rule. The vestiges of these territories are indistinct yet remain embedded within Rwandan society and as such politically inform and influence all post-war redevelopment. In Rwanda ‘development’ is otherwise referred to as President Paul Kagame’s ‘‘Vision 2020 Umurenge’. President Kagame having liberated Rwanda by military force in 1994 ending the Rwanda civil war was officially elected into public office in 2000.

The Presidents ‘vision’ draws from the redevelopment template for Singapore, hoping to economically transform a predominantly low-income agricultural base into a middle-income knowledge based society. Kagame’s vision has elicited reform across all government sectors in tandem with innumerable reconstruction projects across Rwanda.

The growing capital city of Kigali has been remodelled with a new inner-city dense core with financial facilities giving a rather generic CBD quality to what was small provincial town that sprawled over hills and valleys. Rwanda’s countryside of scattered settlements and rich, yet limited, natural resources have been collectivized, reorganized and intensified through economic development policies and programming.

Kagame’s transition from a country that was decimated from war to the vision, and the rapid ease within which modernisation unfolds have made Rwanda the paragon of African development. Responding to the visual immediacy of clean streets and social welfare reform, Rwanda is continually likened by to Switzerland – ironically where the EPFL drone project itself originates. Yet within Rwanda inconsistencies between the discourse of development and realities of the everyday, the vision begins to appear as a desperately held together simulation.

Such contradictions are most visually disparate between how much of the urban poor in Kigali live and the land cleared for new mono-functional building developments. Several high-rises do indeed stand, yet they are often surrounded by empty land parcels that urban farmers have reclaimed, albeit temporarily. Many informal practices of farming and trading within the city do not project the trajectory of development and forbidden. In 2015 Human Rights Watch discovered the ‘unlawful’ detention of homeless, street-children, sex-workers and informal vendors that were systematically rounded up by the Rwandan police and held in what the government refers to as a ‘transit centre’.

This year President Kagame amended the local constitution extending his second term to a third, and potentially up until 2034. The extension of the presidency was suggested to respond to the peoples desires. A view of public opinion gathered by government petition the President stated he was unaware of, that has been contradicted by reports of intimidation and coercion. In 2012 the Rwandan government passed a law allowing it to monitor and intercept email and telephonic exchanges. Since then several journalists and musicians have been jailed based on the content of private conversations (over skype and whatsapp) that were intercepted and construed as collusion against the government. Such accusations against the Rwandan government sit alongside a host of reports, in country and beyond, of assassinations, disappearances and incarceration to political opposition to the ruling government. Open criticism of government politics itself is taboo within Rwanda. Journalist and author Anjan Sundaram’s recent book ‘Bad News’ refers to Rwanda under Kagame as ‘an Orwellian regime’, where a lack of open and criticism of the government is contained through government’s reign over open speech and debate.

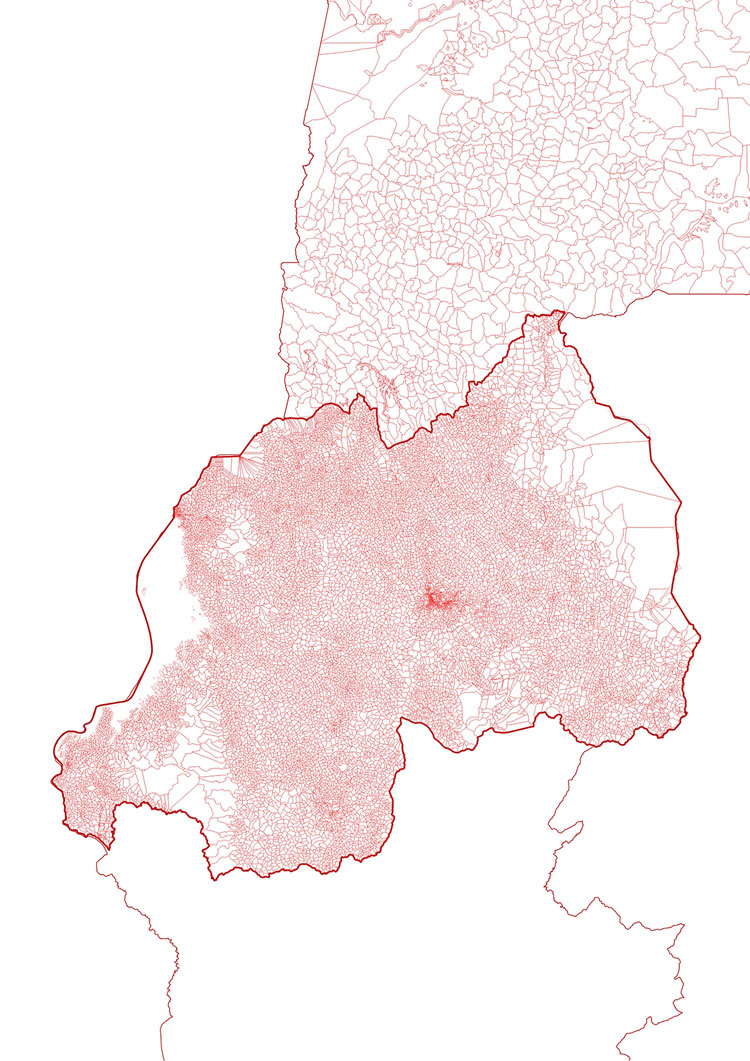

A complex network of surveillance and communicative control has long operated in Rwanda through a system of broadcasted bureaucracy passing through a hierarchy of socially administered units. During the pre-colonial days of Rwandan kingdoms, the hill was regarded as the basis for socio-political unit, divided into neighbourhoods with a sub-leader, under command of a hill chief (Musahara, Huggins 2006). Today the village is the smallest administrative unit in Rwanda, yet an undeclared smaller unit of 10 households overseen by non-salaried yet official representatives unofficially exists (Purdekova 2011). There are an estimated 14,876 village across a population of 10.6 million people in Rwanda. By way of comparison neighbouring Uganda, a country nine times the size with a population of 40 million people has 6,255 village units. The administrative atomisation of social space Purdekova suggests in part ensures ‘Vision 2020 Umurenge’ policy or well-being is effectively implemented, yet permitting the government a panoptic view of all events, across scales of the province to the private space of households with the ability to spread a form of despotism that disempowers (Purdekova, 2011). The english translation for the Rwandan word ‘Umurenge’ translates ‘administrative sector’.

Village Administrative boundaries in Rwanda and section of neighbouring Uganda

I should emphasise, that criticism is not being directed at Foster’s project as it responds to many physical and social challenges that Rwanda presents architecturally. The vaults depicted in the rendered images seem to forge a visual identity with Rwanda’s physical geography and the project has many social advantages of using drones, not least of all increased access to healthcare. Foster’s drone-port is also one of a number of drone projects planned within Rwanda. Nor is the role of drone technology itself being dismissed. Reservations about drone technology are clear, reified recently by Forensic Architecture’s devastating simulation of a Syrian drone strikes on a living room, also exhibited at the Venice Biennale.

Rather this is about the muddy spaces of humanitarian architecture that are paradigmatically prone to being heavily narrated and represented, excised out of socio-political contexts. The resultant effect is a universally positive and distorted view of spaces of development as neutral.

Humanitarian architecture emerges from the same dichotomy development faces; a philanthropic base of empowerment and emancipation that a disembodied process of intervention and imposition. The Congolese philosopher Valentin-Yves Mudimbe considers the African continent as a perpetual space of improvement, and as an invention of the west in which the colonial gaze becomes concentrated. Colonial history as much as we don’t like to talk about it, is linked to development and informs the manner in which we perceive and relate to ‘Africa’. Cultural distance is built-in to the processes of intervention and therefore how context is evaluated, responded to, reflected and re-represented. The origin of the drone-project as described by Foster at the Biennale, emerged from ‘a concept of the continent’ of suffering from a lacking of infrastructure, a high population growth and with ‘little hope of catching up’.

A reduced context is one where architecture disengages from the political and is an on-going crisis that the architectural practice faces. Architecture rarely can bite the hand that feeds it. Kim Dovey call’s this contradiction ‘the silent complicity of architecture’ where real control of the programme is ‘ceded to the commission of the client’. Yet the humanitarian spaces of intervention are fraught with more power-struggles with interests displaced across many’ stakeholders’ and ‘beneficiaries’, less invisible than visible, more remote than proximate.

Drone-ports are planned for 3 locations to give coverage to 44% of Rwanda. One of these locations is the Rwanda-DRC border town of Cyangugu. An area where human life is enmeshed between rebel (pro-Kagame) fighting and the illegal trafficking of high-grade mineral resources, much of which passes through this Cyangugu itself. As binding matters of law can be circumvented declared in the interest of the public good, there is little to suggest that the aviation laws governing drone-technology are beyond reach. In neighbouring Kenya test drone-flights project by Redline were postponed in 2014 due to local government fears following recent terrorists attacks.

Critiques of development are particularly difficult to raise and engage within, as to do so assumes a cynical viewpoint of good intentions. To take up a critical view of social architecture, that invariably manifests from a politicized spaces of development, is rare perhaps silenced by the moralizing dualities of good/bad, development/regression that are crippling and self-perpetuating.

The Rwandan genocide creates a prevailing narrative of hope that indeed captures a universal notion of human desire to overcome the legacy of human conflict. This narrative inseparable from the modernising aspirations of development, creates the grounds in which, most if not all, humanitarian or social architecture emerges in the Global south. Rwanda’s transformation captures the contradictions of development, moreso the Janus-faced paradox of modernity that structurally underpins it – progress appears always out of reach and there are both winners and losers. Architects working in ‘development’ should not give up on the Biennale’s suggestion that beauty and craft is pitted against the challenges humanity throws at us. But to do so we have to come to terms with the profound contradictions that exist within the political contexts such architecture invariably finds itself tangled up within.

What is most seductive about Foster’s project is how narratively architecture is coupled with the positive use of drone-technology towards human goals. Yet when the drone-port is resituated within the political context of Rwanda’s atomising and opaque system of governance the use of the technology, and therefore the architectures grounded claims of good intentions become unstable.

Architecture, like any form of reportage and representation, when excised from its socio-political context, reflects back the ideal scenario into which we gaze. Despite best intentions such decontextualized representations simply depoliticize and dehumanize otherwise much more complex subjects and life-conditions. In Rwanda such complexities are already screened from our view, and ‘the social’ in humanitarian architectural practices, if anything it does, needs to bring these back into view.