How do we balance the needs of people who use and depend upon an infrastructure asset with the needs of those who live in that asset’s immediate vicinity? That question is central to the future of pipeline development as the growth of hydraulic fracking has caused pipeline projects to proliferate. Nowhere was this tension more visible than at Standing Rock, where the indigenous community, concerned about the local impact of the Dakota Access Pipeline, fought the construction of a section they believe threatens their water and quality of life. Exploring this issue is Julian Brave NoiseCat, a writer and policy analyst at 350.org. He takes us through local concerns about the pipeline, while illustrating the consequences of development that excludes local communities from the building process, and identifies the signals of change that herald fundamental shifts in both the demand for pipelines and the way indigenous people are consulted in matters related to infrastructure, construction, and land use.

Demonstrators assemble in opposition to Dakota Access.

A Land of Stark Contrasts

Forty-one percent of Standing Rock citizens live in poverty. That is almost three times the national average. The reservation’s basic infrastructure is chronically underfunded. Schools are failing. Jobs are few and far between, and 24 percent of reservation residents are unemployed. Healthcare is inadequate. Food is insecure. Many depend on unsafe wells for water. Roads are often unpaved. Housing is in short supply, substandard, and overcrowded. If the people of Standing Rock did not take in their beloved family and friends, there would be mass homelessness.

Meanwhile, Energy Transfer Partners’ Dakota Access Pipeline has a price tag of $3.8 billion, bigger—by almost a full $1 billion—than the entire budget of the Bureau of Indian Affairs, which serves 5.2 million citizens representing 567 federally recognized tribes across the United States. The most expensive piece of infrastructure in their community will not be the schools, homes, or hospitals they desperately need. Instead, it will be a pipeline that they have vehemently opposed.

Energy Transfer Partners failed to consult with the community before commencing construction, defying domestic and international precedents embedded in treaties dating back to the 1800s and legislation dating back to the Indian Civil Rights Act of 1968. Had Standing Rock been consulted properly, they would not have given their consent for a pipeline that desecrates sacred ancestral remains, violates their treaty rights, and leaks petroleum into their water supply.

In the short term, Dakota Access threatens the indigenous nations, ranchers, and communities downstream of the pipeline route. Over the long-term, Dakota Access endangers people far beyond. The pipeline will dramatically decrease transportation costs for fracked Bakken shale oil, locking in an estimated thirty coal power plants-worth of emissions per year amidst an imminent global climate catastrophe.

How can pipelines be hammered through Native communities in blatant disregard of treaties signed by the highest government officials of these lands? How can a multi-billion-dollar pipeline take precedence over long-needed basic infrastructure? How is any of this acceptable?

Dakota Access Pipeline protest at the Sacred Stone Camp near Cannon Ball, North Dakota. Photo by Tony Webster.

The Colonial Present

The totality of this picture can only be captured in a word rarely if ever used in contemporary politics—colonialism. Indigenous presence is contained, erased, and then forgotten, so that the United States can continue to live upon and profit mightily from lands taken from indigenous people. Erasure is a double-edged sword. It leads the powerful to underestimate indigenous resistance, opening pathways to victory precisely because indigenous people have been written off.

In a special message to Congress, Richard Nixon inaugurated the current era of Native American self-determination in 1970. Politicians like Nixon saw self-determination as an opportunity to reduce bureaucracy and limit government spending, but it also empowered indigenous people to parlay minor gains in self-governance into a powerful global movement. Indigenous movements from the United States to Canada and Australia to New Zealand won paradigm-changing victories pushing states to forego assimilationist policies and recognize indigenous rights to self-determination and self-government.

These too often forgotten victories laid the political, legal, and institutional groundwork for indigenous people to turn front-line resistance, politics, law, and media into a potentially transformative movement at Standing Rock and beyond. Today, indigenous people stand at the forefront of political action and thinking, fighting for a democratic, pluralist, and post-colonial framework that recognizes robust indigenous sovereignty as essential to the global fight against racism, inequality, environmental degradation, and climate change. In an era of growing concern about these issues, indigenous people can call thousands and even millions of local and global allies to their cause.

Local and Global Allies

Local landowners who don’t want pipelines in their backyards created an unlikely but powerful coalition called the Cowboy Indian Alliance, which played a crucial role in persuading President Obama to reject Keystone XL and will stand against its reincarnation under Trump.

The labor movement is another potential ally for the indigenous movement. While laborers have little choice but to take work where it’s offered, the unions that represent them might be mobilized against the industry and in favor of emerging and promising job-creating industries like renewable power and resources. Unions were divided in their support for Dakota Access, but with dialogue between the indigenous and environmental movements and the rise of alternative energies, they may yet be persuaded to oppose pipelines in the future.

Far away from oilfields and pipelines, the indigenous movement has allies who can help fight developments that violate indigenous rights. Many investors, including prominent banks, cities, and pension funds have divested from Dakota Access parent companies. Movements to divest from fossil fuels can target companies seeking to exploit indigenous lands. Progressive environmental and financial regulations could discourage risky natural resource speculation and divert and diminish returns on capital flows to these industries. In response to the opinions and demands of their citizens and lawmakers, cities like San Francisco, Seattle, and Davis are withdrawing their money from banks that support Dakota Access.

Foregoing a fully inclusive approach to stakeholder engagement and indifference to indigenous concerns came with serious consequences that are still unfolding even now as oil begins to flow through the pipeline.

A November 2016 protest against DAPL in front of San Francisco City Hall.

Disrupted Production

Fracked oil costs more to refine and transport to market than other forms of crude. This makes it a more risky—and more dangerous—business.

The decision not to consult Standing Rock prior to construction was surely one rooted in financial expediency. However, given the length of delay and negative attention drawn by the standoff, foregoing a fully inclusive approach to stakeholder engagement and indifference to indigenous concerns came with serious consequences that are still unfolding even now as oil begins to flow through the pipeline.

Investors, bankers, and business partners are risk averse. They don’t like delays, and they don’t like bad headlines. Standing Rock produced both—and similar acts of resistance are increasing in number. Engineering consultants Black and Veatch noted in 2015 that the delay caused by opposition groups was the biggest source of concern among industry executives. Litigation against indigenous claims is costly and can impede and even halt natural resource development on and across indigenous lands.

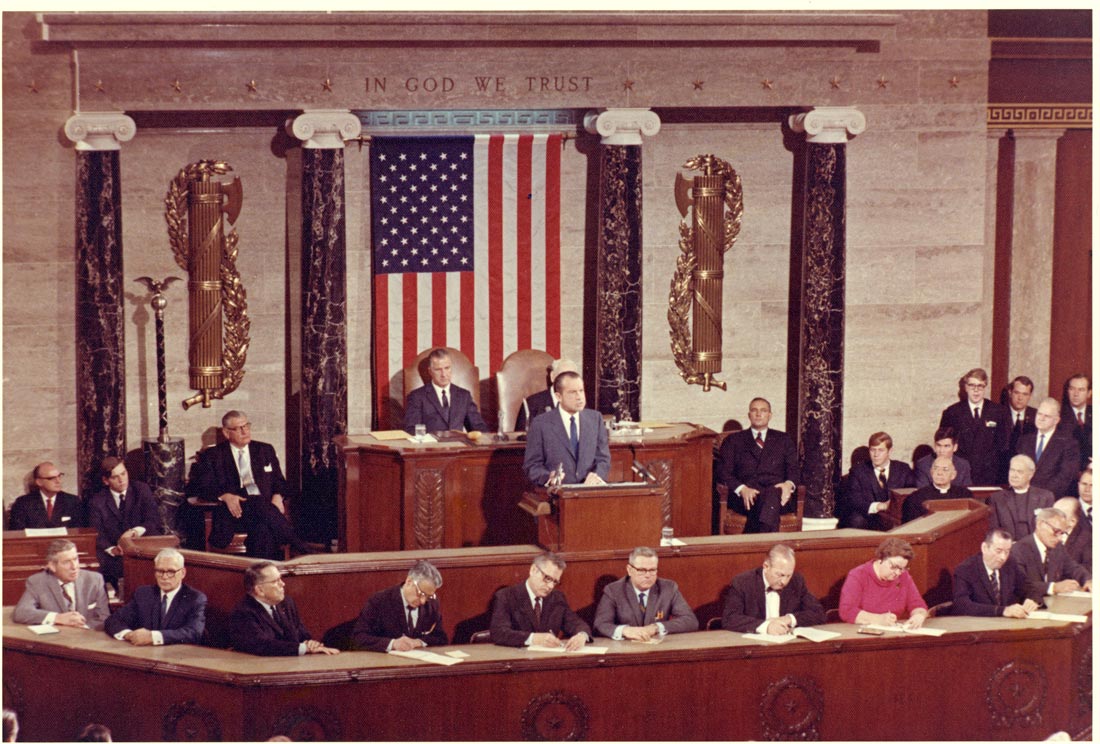

Richard Nixon delivers his 1971 State of the Union Address. Photo via NARA.

Infrastructure in an Indigenous Century

The United Nation’s framework of Free Prior Informed Consent is the starting point for indigenous movements and progressive parties seeking to reshape infrastructure and policy and achieve more just outcomes moving forward. Examples of effective progressive models and policies around the world that might be emulated include the Waitangi Tribunal and Settlements in Aotearoa/New Zealand, the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples in Canada, the plurinational constitution of Bolivia, and the White House Tribal Nations Conferences hosted by the Obama Administration.

One promising precedent on the path to a post-imperial future has emerged in Aotearoa/New Zealand, where, through the Waitangi Tribunal, the Whanganui iwi Maori recently won a 140-year legal battle to recognize that their ancestral Whanganui river has legal rights equal to those of a human being.

The Whanganui settlement, which was signed by the Whanganui iwi in 2014 and enacted into law by New Zealand parliament last week, established two guardians to act on behalf of the river, one from the crown and one from the iwi. In addition to legal recognition of the personhood of the Whanganui river, the settlement provided financial redress to the iwi of NZ$80m, and an additional NZ$1m contribution to establish the legal framework for the river. While the implications and effects of this legal experiment are yet to be seen, this is a potentially revolutionary precedent that offers a path forward for redefining relationships between governments, indigenous peoples, and the land in the 21st century.

This more equitable future springs from dialogue with indigenous leaders and communities. It is rooted in recognition and respect for indigenous sovereignty.

Instead of building pipelines that threaten water, land, and life, we must invest in schools, homes, hospitals, transportation, and cultural centers that enable indigenous children and nations to flourish. We must return lands and resources to indigenous control and include indigenous voices in decisions that shape the infrastructure of tomorrow. We must recognize what indigenous peoples have believed all along: that land and water are sacred living ancestors whose well-being humanity depends upon for our continued health and existence upon this earth. This planet’s greatest resource does not lie in the ground. It lies in the people, places, and communities who lead the way forward to a more just, equal, democratic, and pluralistic future for the first people of this land and all who share it with us.

Many, with good reason, have declared this the Chinese century. But in the wake of Standing Rock, growing support and strength of the indigenous movement and emerging local and global trends suggest that, when we envision a more just, equal, and green world, this might also become the indigenous century.