We believe that cities need both city planning and city making. While city planning addresses the physicality of the ville, city making addresses the sociality of the cité. But both processes should also address the need for a cohesive and political understanding of the urban phenomenon as a whole, therefore assuming its role as polis. City planning has consolidated, well-established methodologies, expertise and regulatory frameworks that are constantly being updated. City making, on the other hand, takes a less structured, more flexible, and more fluid approach, both due to its relatively short history and to its nature – as it relies intensively on an open-ended collaboration between organizations and citizens. We define city making as those processes that result in the social and material construction of the city by means of specific projects or initiatives. Design for city making mobilizes disciplines that traditionally have dealt with the city (architecture, urbanism, landscape) but also includes all other design areas (service, product, graphic, interaction) that only recently have begun to consider the city as their natural terrain.

These two approaches are radically complementary and should be used simultaneously. Moreover, we are beginning to have novel conceptual and instrumental frameworks, such as ecosystemic urbanism, superblocks, or plug-ins, that help us (even compel us) to relate city planning with city making to form a richer and more complex approach to the combined physicality, sociality and polity of contemporary cities.

Of course, neither city planning nor city making processes guarantee desirable outcomes per se. Social oversight and scrutiny are necessary. City planning and city making projects have different social and political motivations and implications. They can produce inequalities, segregation and urban commodification, or they can promote equality and create a diversified and vibrant urban fabric. The first kind are driven by the interests of those who consider the city, in all its aspects, as a marketable good. The second, which we espouse, posit the city as a common good. In consequence, we advocate city-making initiatives that are situated practices, in which spatiality in general, and the notion of collective spaces in particular, play a crucial role. Complex and evolving forms of spatiality work to articulate social, political and cultural concerns and ground them in specific hybrid physical and digital milieux where rich urbanity unfolds.

Design is an agent that affects the state of things. By adopting a point of view internal to the system on which it operates, it construes visions, proposes solutions and produces meanings. In other words, it generates transformations that are both symbolic, operative and semantic. In turn, this action on the world can be seen as a process and as a product. In the first case, we are referring to the interactions between a group of people that generate a result. In the second, the result of the action is considered. In turn, the result of the design process can present itself in very different forms: from industrial products and architectural structures to the products of contemporary design, which include services, places, events, communication strategies, digital platforms and applications, and different combinations between them.

It follows that the times and ways in which design participates in city making are also varied and articulated. Nonetheless, they share some common features that derive from the very nature of design: they look at the city from within (i.e., they take the point of view of the actors involved); they connect the built city with the lived city (i.e., they bridge technical-material dimensions with socio-cultural dimensions); and they tend to operate “by projects” (i.e., transversal undertakings collaboratively carried out to achieve a particular aim, which makes it possible to account for the complexity of the city without reducing it). These characteristics of contemporary design make it, for better or for worse, a powerful actor in urban transformation.

In fact, design has many responsibilities in the current evolution of the city towards socially and environmentally unsustainable forms. However, for the same reasons, it can, and indeed should, actively participate to shift these undesirable dynamics in the opposite direction: that is, towards collaboration, resilience and sustainability. We promote an approach to contemporary design that involves discussing its products and how they can help in the ongoing process of city making, and, in particular, how they can act as a bridge between the built city and the lived city.

Plug-ins and Complex Systems

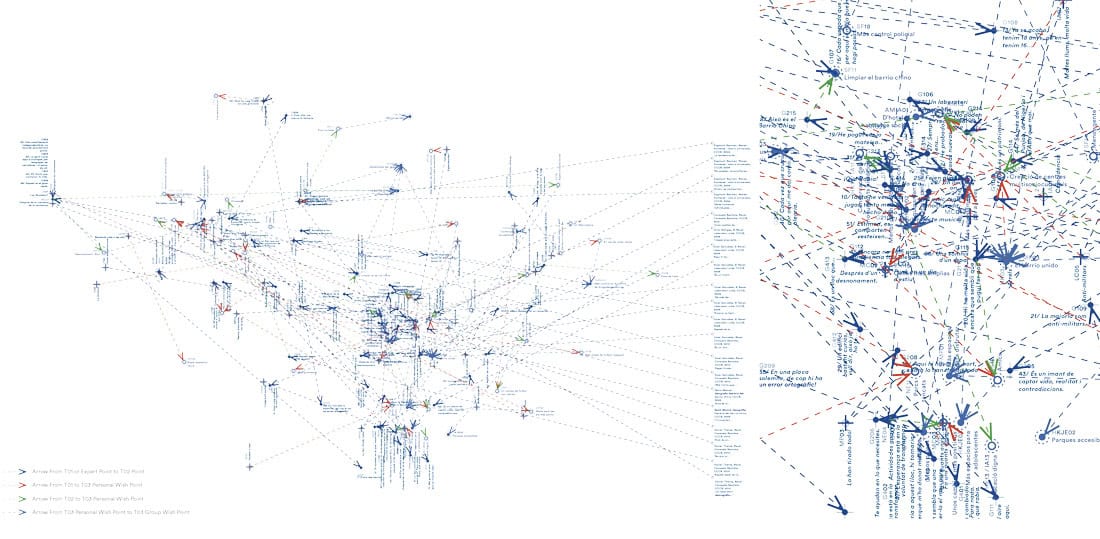

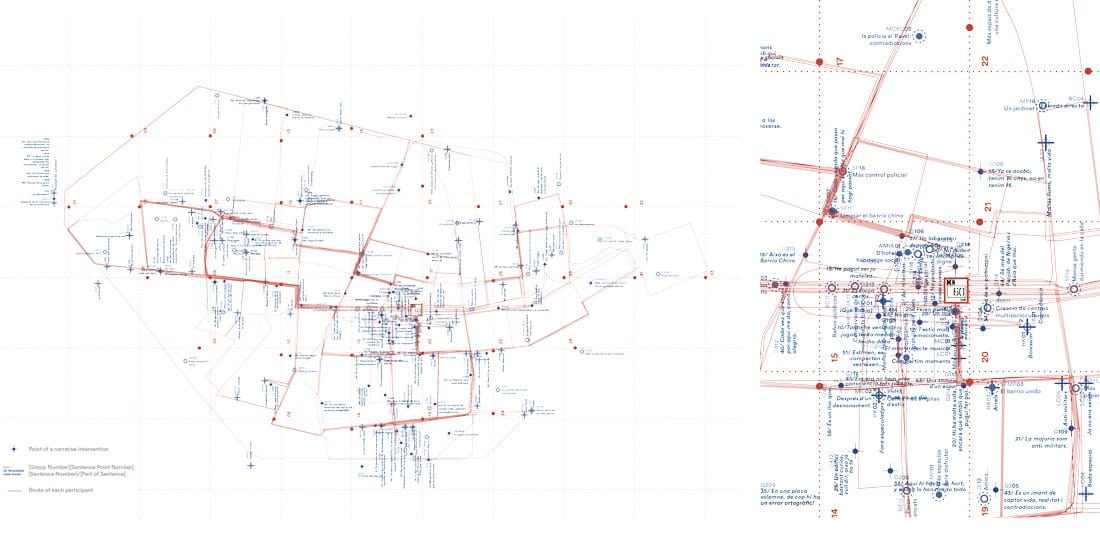

In this book, plug-ins are understood as agents that unveil the multi-layered essence of the city. And by unveiling this essence, they help reflect on the physical, social and political assumptions that cities inherit because of their high complexity. Plug-ins, as active, performative and material intersections of reality, become stepping-stones in the potential re-configuration of the material, relational and semantic assumptions that shape the city.

In a literal sense, a plug-in is “a small device or computer program that is designed to be used with and fits into a larger one” (Cambridge Dictionary). This definition can easily be applied to our discussion: the design outcomes we refer to here (which have been conceived and developed in the Design for City Making platform) are plug-ins because, as anticipated, they are physical, digital and/or relational assemblages designed to fit into an existing system of structures and relationships (the city), changing it in the desired direction.

It seems to us that the image of design as a plug-in is useful because it helps to focus on three very relevant issues: (1) design is a part of a larger system: in this case, the city; (2) design is a subsystem to be used with and fit into a larger system; (3) its raison d’être is to modify the system to which it refers. These three points are important because they offer a guide for designing in complexity. Not only do they remind us of the systemic nature of the reality we are confronted with, they also remind us of our limits and the limits of what can be designed. Moreover, they tell us that, whatever the limitations, there is always something that can be done, something that can be plugged into the system to engender new urban realities.

Additionally, the image of a plug-in highlights the possibility of designing artefacts that are endowed with their own autonomy (definable through a set of features), the actual value of which can only be assessed by observing the change they generate in the larger systems into which they are inserted. In that sense, considering our experiences with design for city making, what are the effects on the urban system that, as a whole, the proposed plug-ins aim to achieve? Is it possible to sketch out the components that make up these plug-ins based on their different operational contexts and the specific effects they pursue?

The plug-ins that were conceived and developed as part of Elisava’s Design for City Making platform have a common characteristic: they aim to enrich and strengthen the fabric of both the built and the lived city. In other words, even in the case of a dense city, like Barcelona, it can be useful to work toward increasing its relational density. There are several reasons for this: because the city may be physically dense, but socially deserted; because some relational possibilities cannot be transformed into collaborative practices; because a social fabric may exist but may have degraded; or because the fabric of the built city has become inadequate and needs to be regenerated.

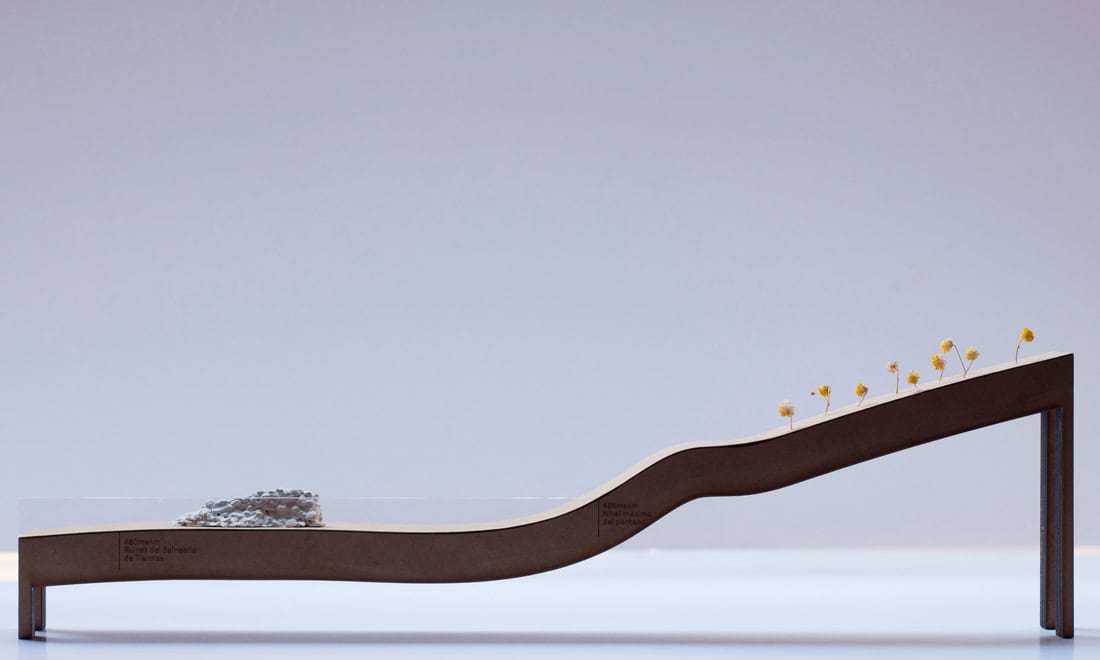

The existence of these different contexts requires different city-making interventions and therefore different design plug-ins. Based on the experiences we have accumulated, we have deduced that every plug-in has three basic components, which we call generator, mediator and identifier. Just as the four basic nucleobases (cytosine, guanine, adenine and thymine) make up DNA molecules that carry genetic instructions for all known organisms, so all design for city making design initiatives are made up of these three basic components. Different proportions of these components correspond to different roles the plug-ins can play in the urban system.

Identifier describes the symbolic, mnemonic or consolidating component of a plug-in. By recognizing, visualizing and labelling spaces and practices that prompt a collaborative city, identifiers contribute to building or maintaining a level of conscious awareness of design for city making initiatives.

Mediator describes the bridging, negotiating or conciliating component of a plug-in. As social condensers that distill existing practices into new relational landscapes, mediators reinforce existing dynamics by producing new relationships that activate the urban system.

Generator describes the creative, transformative or founding component of a plug-in. As game-changers that introduce new elements into a pre-existing context, generators transform the initial conditions by adding another layer into the mix that reshuffles the urban system and opens up new expectations and possibilities.

It is important to clarify that generators, mediators and identifiers are not mutually exclusive taxonomies, but rather dynamic indexes that allow us to characterize, relate and compare all design for city making initiatives.

Let’s consider, for example, a group of wooden chair prototypes designed by first-year design students and installed along La Rambla. They act as a generator because they change the normal setup of public space, interrupting the habitual flow of people and offering a space to linger on a highly dynamic street. They also act as a mediator inasmuch as they create opportunities for conversation between residents and tourists, breaking the normality of their mutual indifference. Finally, they act as an identifier because they emphasize both the tourist-local conflict and its potential solution through enhanced interaction, and a design school’s contribution to enriching La Rambla’s social makeup through a yearly event that ties curricular activity with social impact.

Therefore, the plug-in components overlap with disciplinary niches (space, service, event, product, interaction, etc.) and design tools (triggering, direct action, mapping, concept generation, prototyping, storytelling, etc.). In conclusion, the definition of generators, mediators, and identifiers is an attempt to describe the three different performance poles that articulate any specific contemporary design initiative when applied in design for city making, especially when cities are considered as a mesh of interactions between inanimate and animate natures and between human and more-than-human entities.