In Siloé, entire generations grow up without comprehensive early childhood care, without pedagogical innovations or arts education, without recreation or sports, cultural activities or citizen participation to keep them away from violence.

Here, children are statistical improbabilities who are born into poverty, grow up in insecurity, and then become young people with a genuine, daily feeling of injustice, who demand the recognition of their rights with violence. They know that there is no future for them in a society where they are kept invisible and where the greatest shortfall is not in a lack of talent, but a lack of opportunity.

The uprising in 2021 revealed government neglect, a dearth of social investment and the stigmatization of a community that has created a strong social fabric despite not even having public deeds to their homes. People have built the neighborhood with their own hands, and they have managed to improve their living conditions through work groups. However, the lack of urban quality, effective public spaces, and green areas to support children’s development and enhance their abilities at all levels has been a historical social debt.

The Jaime Rentería child development center is located in Siloé, a popular neighborhood in the city of Cali, Colombia with more than 100 years of social and cultural history. The neighborhood’s informal origins date back to the settlements built by mining families when coal exploitation was predominant in the area.

It is located in front of the cemetery, at the convergence of roads belonging to an irregular urban fabric that has occupied watercourses, growing densely across high-risk and difficult-to-access slopes, and leaving few public green areas. In this context, the child development center is an example of how public architecture is a political tool in Colombia, of how leaders manifest their positions on social welfare through buildings.

With this center, also called the “Cradle of Champions”, the municipality had the opportunity to show how education can be constructive, recognizing the value of a community that has made significant contributions to the city. It was a chance to rebuild trust and a sense of belonging in Siloé, the only neighborhood in Colombia that has produced two Olympic medalists, athletes who grew up playing on its intricate streets, stairways and passages.

The project is an urban intervention intended to foster active citizenship, while recovering the environmental values of the site and offering a new support to community life, connecting people through an inclusive public space with an ecological and environmental potential, centered on a building for children with an institutional image that represents a powerful commitment to the neighborhoods’ ongoing formalization.

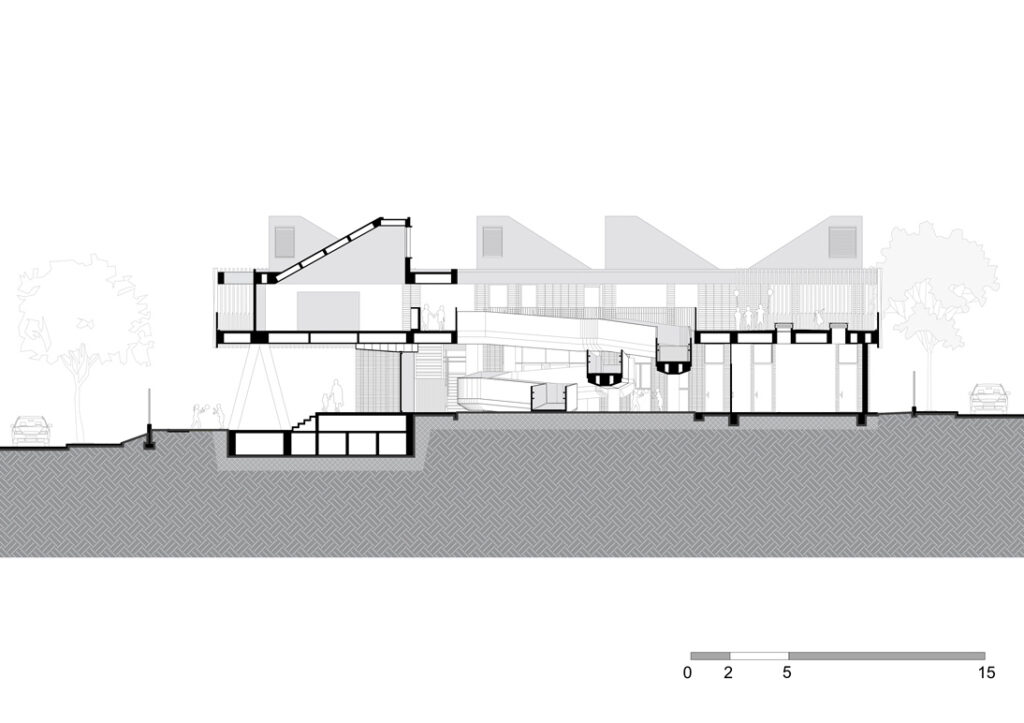

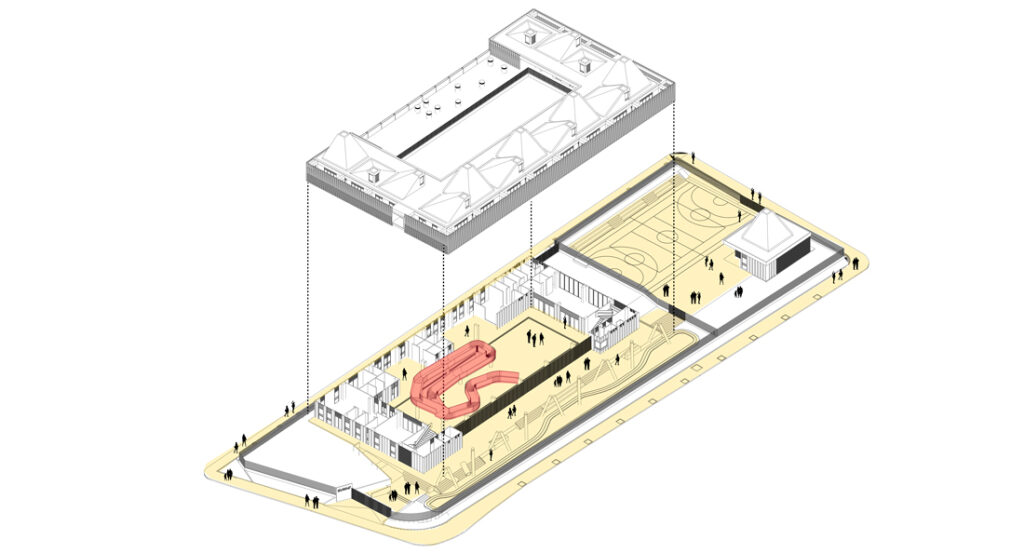

Since the users are the youngest children in the community, the design isolates them from the intense surroundings, situating the classrooms at a safe height, like a nest. This double phenomenon – the need to generate new areas for social contact, while also providing protection and isolation for the children – was decisive in the building’s architecture. The decision to segregate the classrooms away from the public access activated the urban effect of the building.

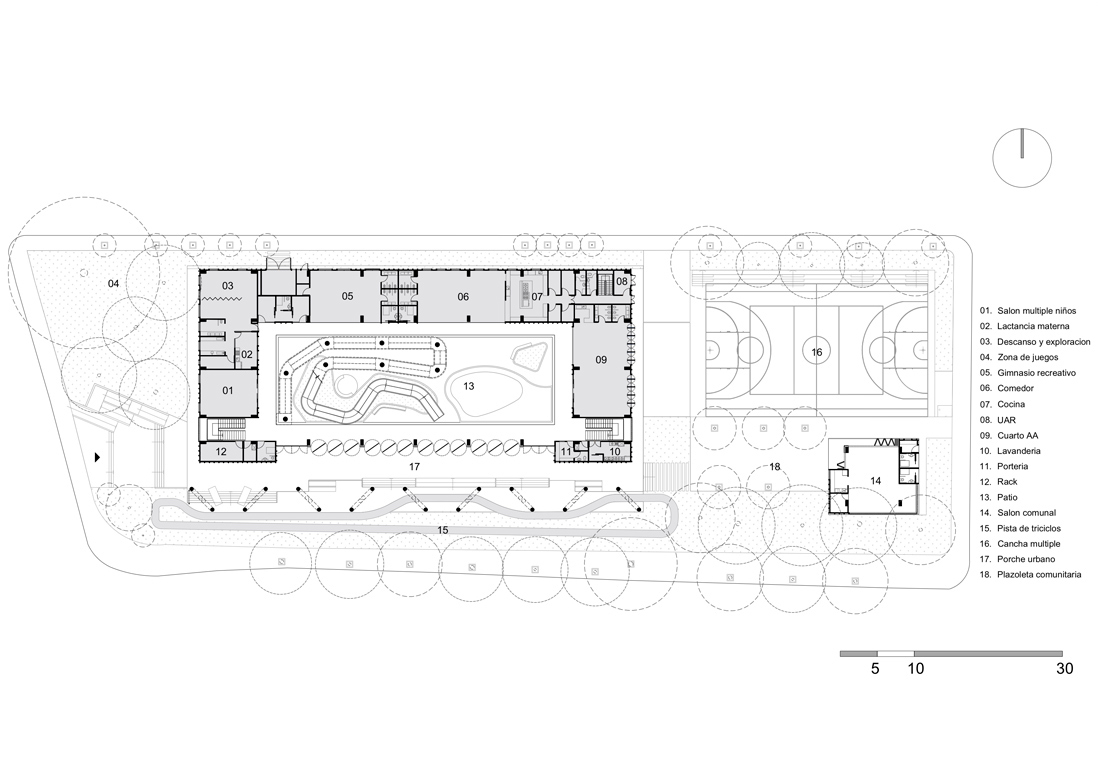

A simple volumetric strategy connects a porch to a play area. By creating an open floorplan, pulling the wall back, and supporting the volume atop a colonnade, a threshold is generated that resolves the transition between the public space and the common areas. This mediation space between the building and the city has a scale that provides spatial quality, sun protection, and a welcoming atmosphere for the people coming to pick up their children.

“A child can only learns when there is emotion.” – Francisco Mora.

Some of the architectural elements highlight the informal quality and lend meaning to the building. These conceptual transfers anchor the building in the neighborhood’s specific circumstances, where each element fulfils a function.

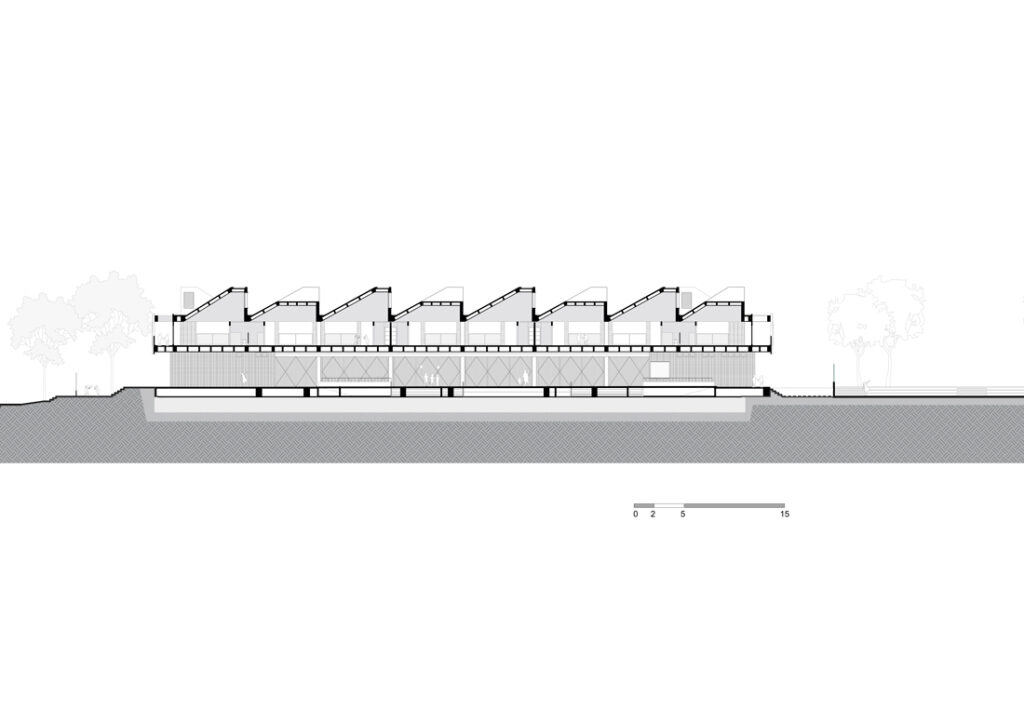

The porch can be used as an extension of the courtyard when the gates are open. A “buttress”-style colonnade supports the volume of classrooms, giving the sensation of both weight and lightness, movement and stability, typical of hillside stilt constructions. An attractive ramp/slide adds dynamism to the playground, while recalling the paths, stairs, galleries, and organic passageways that connect the houses in the neighborhood. The independent skylight roofs are staggered and form a changing profile for the volume. They are clad in blue to create an effect inter-visibility from afar between the neighborhood and the building.

The use of primary colors compensates for the external hardness of the volume and its concrete. A patio around the perimeter is an extension for the classrooms, while housing the gardens and serving as a buffer from the street. The vertical screen made from prefabricated concrete elements serves as sun protection, and at the same time, is a shield against stray bullets in an area of frequent clashes between gangs.