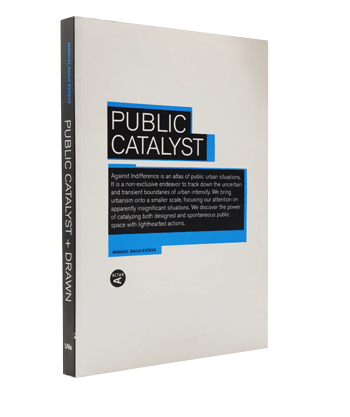

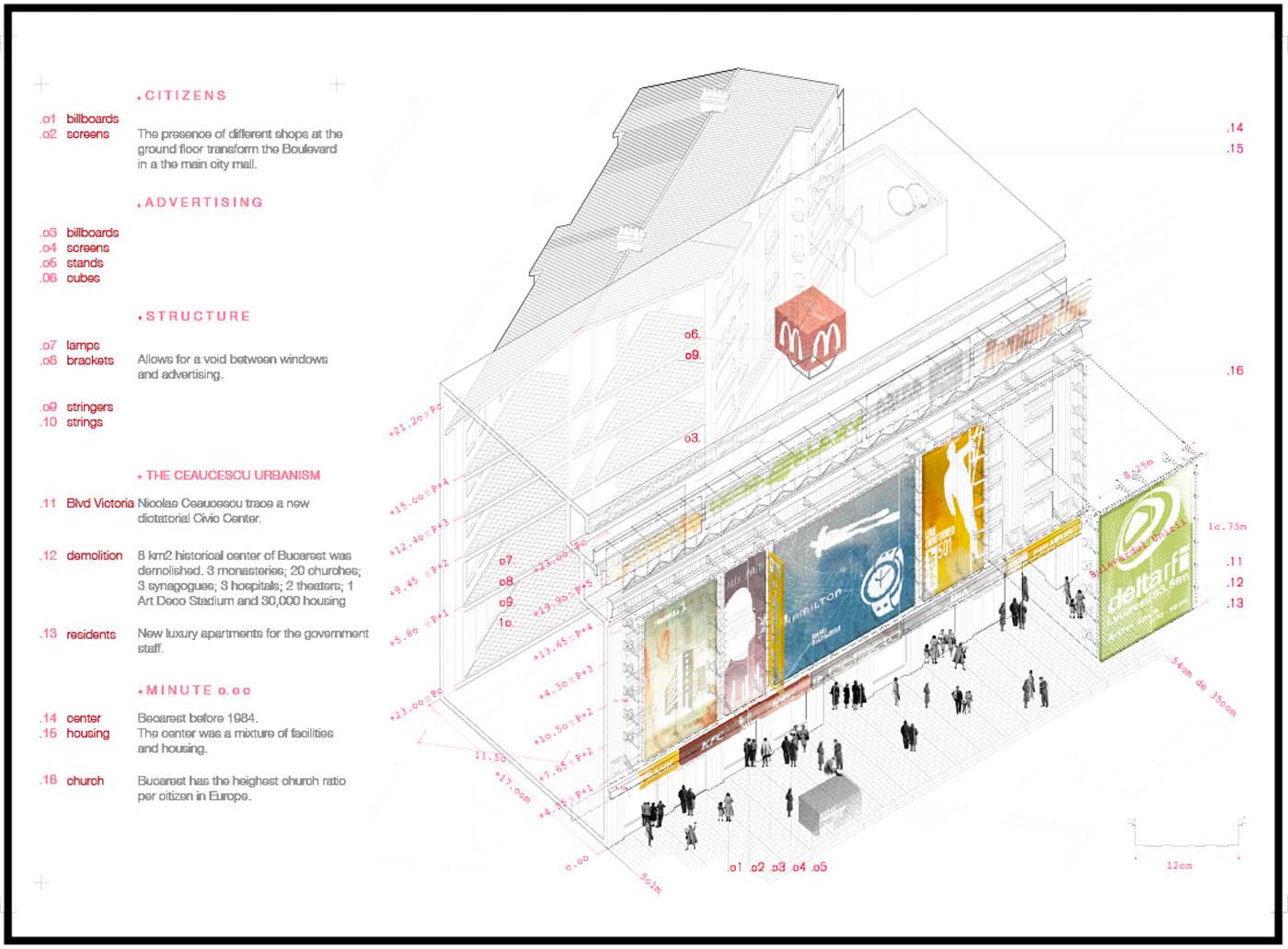

Urbanist Ceaucescu.

It’s impressive “to have a walk” using Goggle Earth over the city of Bucharest. It’s actually quite worrying to discover Ceaucescu’s concrete-curtain buildings, extended indifferently over the city, trying to construct a fake scenery that conceals the reality of its people without freedom. It is possible to imagine the atrocities that this dictator was capable of realizing, just by observing the photomap of the city.

Ceaucescu, a delirious despot, seized power of Romania in March 1974. His political idea of constructing a “socialist society with a multilateral development”. In order to achieve that, he organized a program of homogenization of the population, consistent, in many occasions, of devastating villages and relocating its inhabitants in new “modern” housing estates.

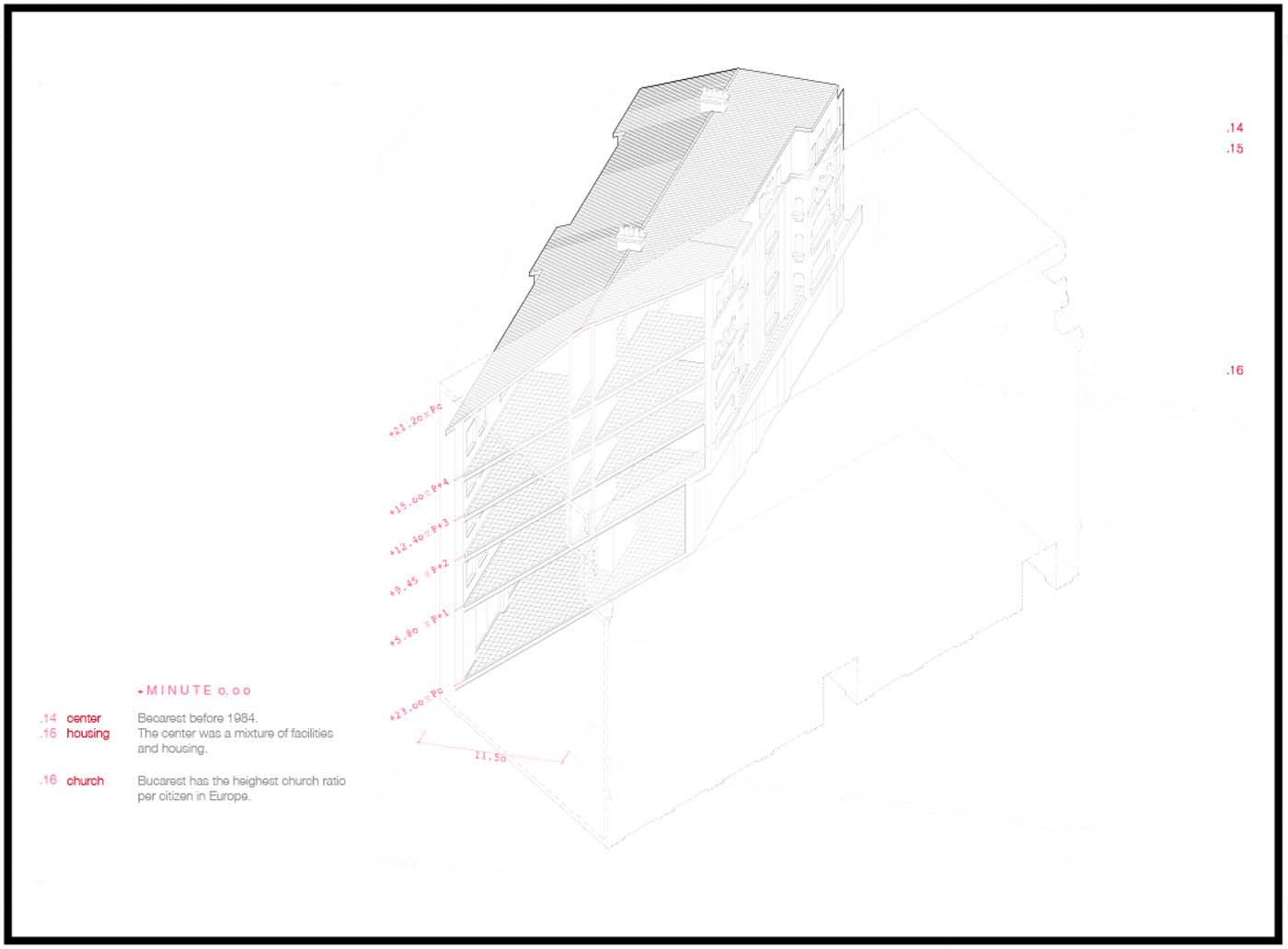

The construction of the Civic Center

His political program also included the reform of the country’s capital, Bucharest. In 1977, after a strong earthquake that destroyed the city, Ceaucescu decided to place his new residence and the new center of the country’s power in the old part of Bucharest, supposedly replacing only the harmed ones. However, influenced by the monumental North Korean aesthetics and with the idea of placing these new buildings in the least seismic zone, or in other words, in the least affected neighborhood; he knocked down more than 40.000 houses, removed hundreds of thousands of inhabitants of the historical neighborhoods and leveled the hill of the central area of Bucharest. The architect Ioana Marinescu, gathers diverse interviews of survivors of that barbarism, in her report on the memory and the identity of Romania. With sadness, the damaged families remember how, in a few days, they were removed to allow that the president Ceaucescu could locate his house, the new Palace of the People, and the avenue of Victory, with three kilometers of length, over their houses.

Concrete Curtains

Richard Sennett, in his article “The new capitalism, the new isolation”, comments that modern society, based on flexible work, has ended up building indifferent cities. According to Sennett, the flexible work has finished substituting the model of long-term work. The idea of being faithful to a single enterprise during an entire work career has been replaced by the execution of sporadic jobs consisting of specific and limited tasks. Sennet puts forward how this new capitalism, that demands flexibility to survive, ended up creating neutral and impersonal areas; areas with the capacity of being modified with ease. Sennet maintains that flexible time is consecutive, instead of accumulative: a project is developed in the first place, then, when finished, another one takes place, even if it’s not related to the first one, and so on.

The arrival of capitalism

In the Avenue of Victory of Bucharest, Ceaucescu tried to erase any track of the accumulative time of the history of Romania. He thought that he could suppress the identity of a whole nation by destroying the architecture of the capital’s historical center. Ceaucescu was trying to raise a new “communist” space of relation, by devastating the history and constructing a few new heavy concrete buildings above it. Although his monumental urban project tried to become consolidated by repeating and extending the model of concrete curtains to other neighborhoods of the city, it was always, from the beginning, a failed urban project. The Avenue of Victory and the rest of the streets that Ceaucescu executed were empty, dead spaces and without any type of activity.

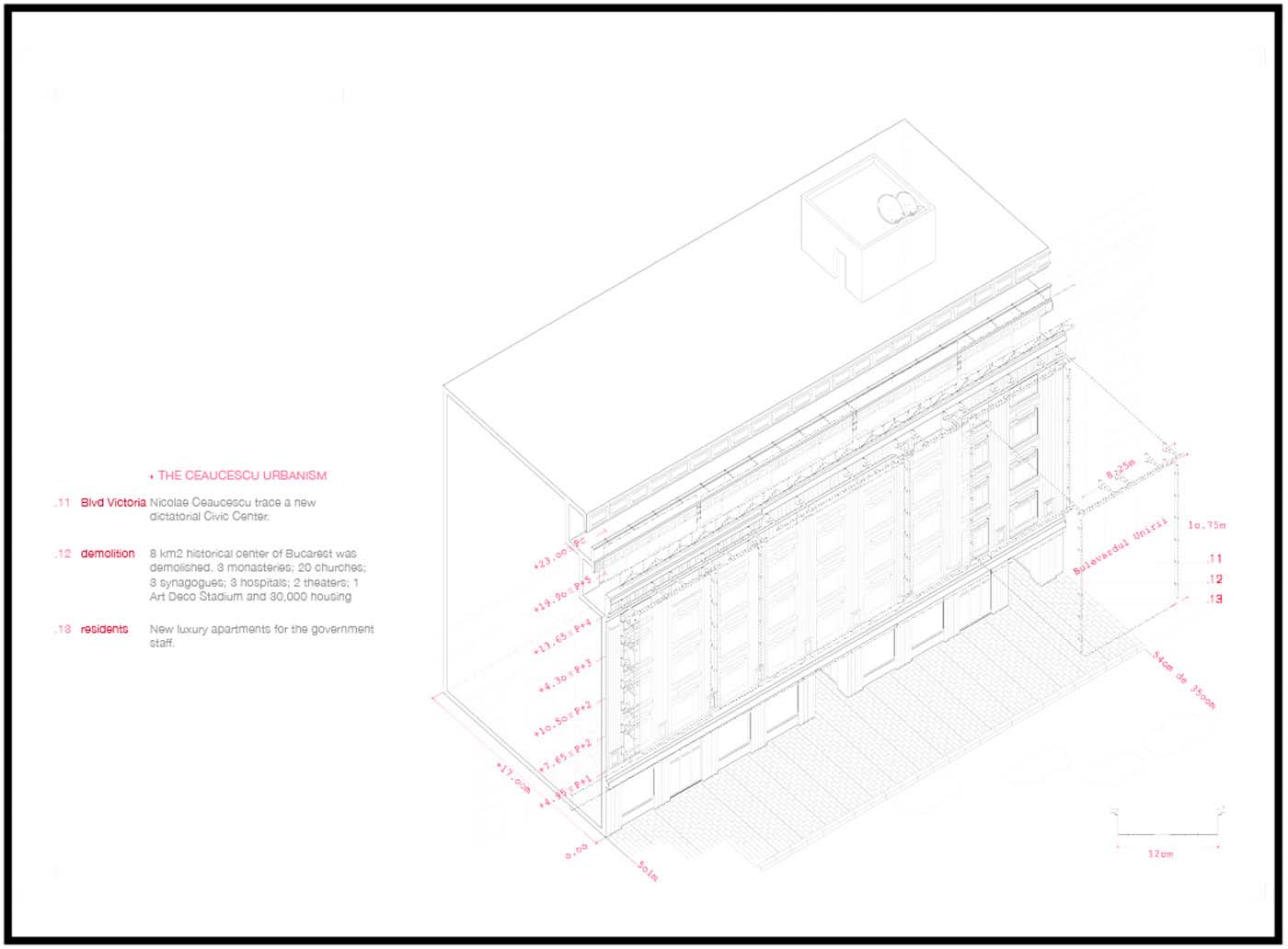

It wasn’t until the arrival of capitalism and trade that a new, light and flexible curtain, support of commercial propaganda, was superposed to the concrete fronts of the streets planned by Ceaucescu; and these have turned those dead spaces into real spaces indeed.

The appearance of commerce has suddenly gathered the presence of the accumulative time, the weight of the history, and the consecutive time of this new capitalism in the same place; magically constructing the most important spaces of relation of the city.