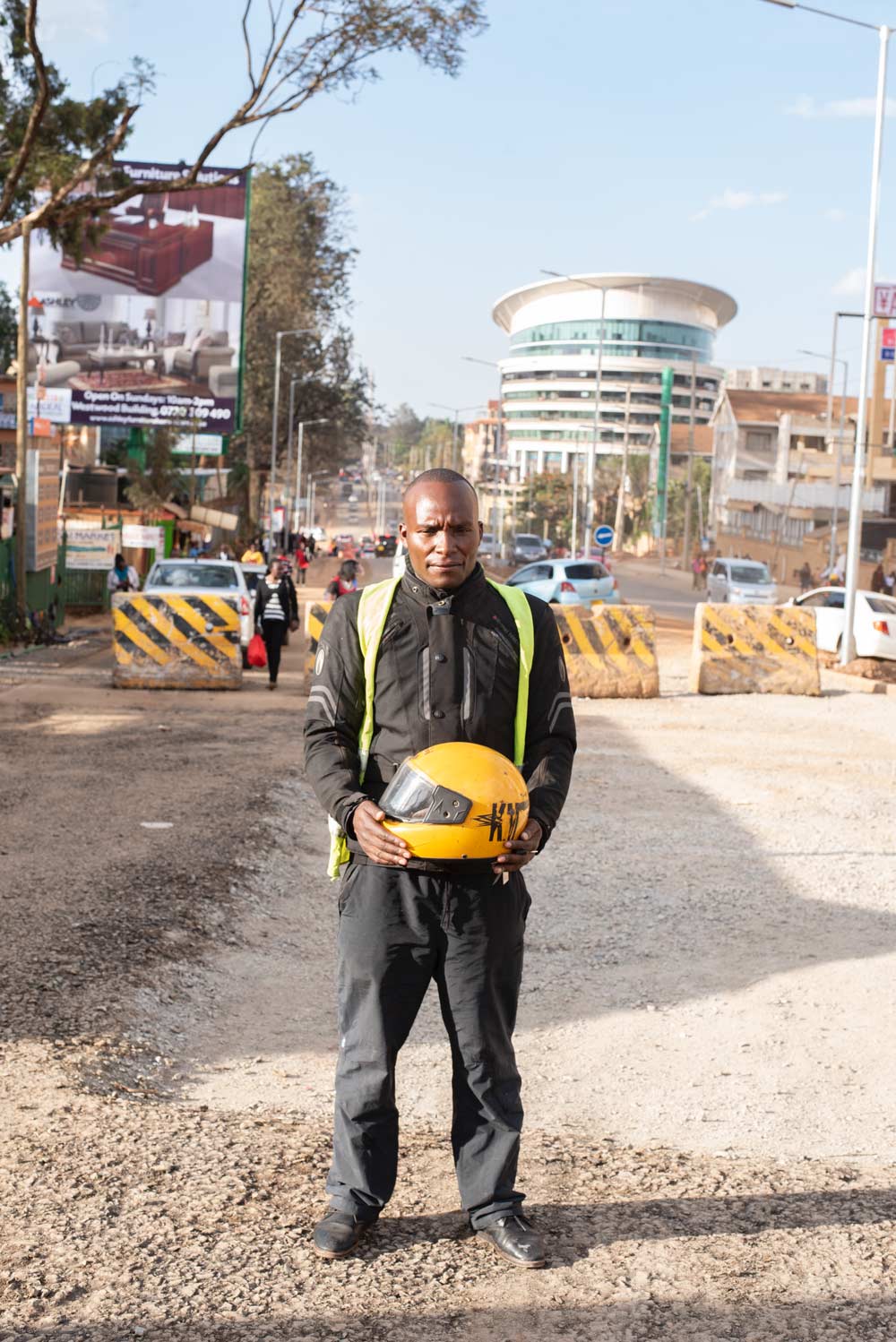

This is the third in a series of articles which highlights the complexities of Moving in Nairobi through the eyes of four commuters as they walk, ride motorcycles (boda boda), take buses (matatu), and hire Ubers from the wealthy neighborhoods adjacent to the United Nations to the low-income communities in the city center. Three and a half million people move through this East African capital every day, and the lack of coordinated transportation planning often causes the city to grind to a halt. Our third story is from Nelson Mangwali, who has one of the most dangerous transportation jobs in the city: driving a boda boda.

Nelson is among the city’s hundreds of thousands of boda boda drivers who ferry passengers to work and around town. He works particularly in Nairobi’s wealthy neighborhoods of Gigiri, Runda, Westland, and Parklands. Nelson owns his boda boda outright and is always prepared: he carries a small toolbox with wrenches and screwdrivers to immediately fix any issues his motorbike might have.

Riding a boda boda is the best way to beat the infamously brutal congestion in Nairobi: while buses and taxis can sit in gridlock for hours, boda bodas can weave between lanes and travel more easily on narrow or unpaved roads. Some of Nelson’s customers are UN officials, who rely on his driving to get to work on time each morning. Because Nelson is known for his safe rides, he has standing daily pickup times and monthly salary arrangements with some of his customers. A typical ride on Nelson’s boda boda costs about 200 Kenyan Shillings, or $1.94.

“My highest priority is to get customers to their destination both safely and on time.”

But work is not that stable for all boda boda drivers. In 2017, boda bodas accounted for a shocking 70% of newly registered vehicles in the country, and because of these ever-swelling numbers of boda bodas on the road, competition for passengers is stiff. Some drivers stand out from the crowd with vibrantly painted bikes and gear, and for a steady stream of passengers, most are increasingly relying on ride-hailing apps like Uber and Taxify, through which passengers can hire a boda boda instead of a car.

Though riding a boda boda is certainly the fastest way to get around town, it is also one of the most dangerous: data from 2017 shows that 1,177 people died in motorcycle crashes in a 12-month period. Often, fatalities and serious injuries occur because the driver and the passenger are not wearing enough protective gear, such as biking jackets or – more importantly – helmets. There is also a new app called Safeboda that is meant to do a better job at checking drivers’ safety records, providing helmets, and ensuring the vehicles are well maintained. Nelson always provides a helmet for his customers.

There have been recent efforts to regulate the boda boda industry, due to the increasing use of boda bodas by gangs in the city center. With hundreds of thousands of boda bodas on the road there was no easy way to recognize or identify the vehicle or driver; gangs have taken advantage of this industry-wide anonymity and have begun using boda bodas as getaway vehicles. Gang members are known to drive alongside pedestrians and grab their bags before speeding off with no way to be identified or caught.

In 2018, the Boda Boda Association of Kenya introduced an effort to defeat this criminal activity by establishing a boda boda registration system. In this new system, boda boda drivers wear a yellow reflective vest with a registration number on it. Riders and other drivers can then type this number into the Association website and get the boda boda driver’s name and motorcycle registration number.

Another effort to regulate boda bodas, spearheaded by the Nairobi County Government, was more extreme. In January 2018, the government announced an immediate ban on boda bodas in the city center. Boda boda drivers had to drop their passengers off at locations around the perimeter of the city, from which the commuters could catch buses to work.

The effect of this ban on boda boda drivers and the passengers who rely on their service has been mostly negative. In the first year of the ban, many motorbikes were impounded, and their drivers had to pay a steep fine; passengers and drivers alike have complained that the sanctioned dropoff stations, which are few, become overcrowded at peak commute times. Because of this overcrowding, more and more boda bodas are trickling back into the city center, where drivers still face fines and vehicle impoundment if caught by the police. As of summer 2019, the government had released 800 of the impounded motorcycles back to their drivers, encouraging them to follow the rules of the ban.