Outside territory?

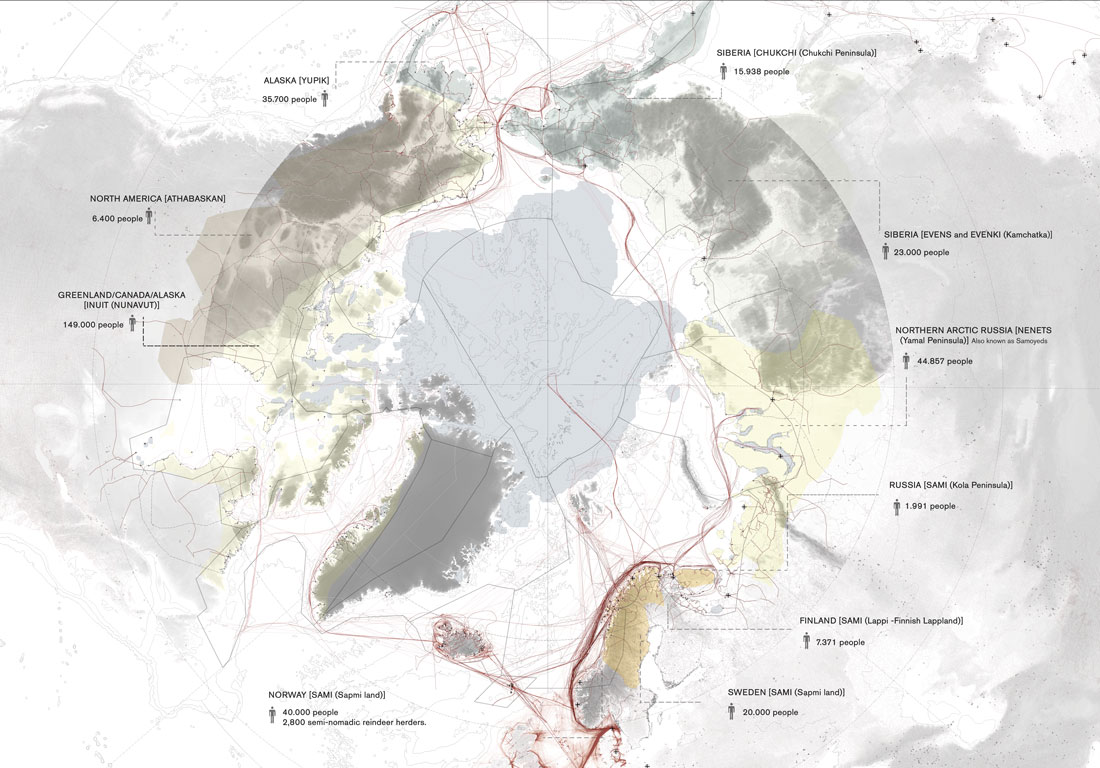

Climate-change narratives are re-shaping the way in which we see the world. The Arctic and the Antarctic have been historically left out of conventional world maps or unproblematically distorted in such maps. Unfortunately, we are growing more and more accustomed to semi-apocalyptic polar projections, such as the North Pole atlas (Figure 1), due to rapid climate change fuelled by the common (global) denominator of excessive fossil-fuel consumption. The melting of the polar ice fields, the collapse of glaciers, and the resultant alteration of the attendant ecosystems (e.g., tundra and fisheries) has led to economic and military competition over the control of these once-buried resources, once-frozen polar sea routes and once-ignored international borders.

Figure 1: Seasonal North Pole atlas projection showing clashing interests between indigenous communities, resource extraction, shipping routes and states’ borders. © Nataly Nemkova & Penny Fyta

The relative stasis of Figure 2 contrasts with the actual restless or ceaseless movements of native peoples and interlopers in the arctic region atlas. Despite the apparent white calmness of the icy environment, this is an inhabited, dynamic and fragile environment deeply conditioned by the materiality of watery states (Elden, 2017, p. 215). It is busy with migratory patterns, nomadic movements, shipping routes and shifting borders. In these flows, ice connections and discontinuities, at the mercy of climate change, play a crucial role, which can be advantageous or detrimental for particular interests and needs. The seasonal versions of the atlas show the ice disruptions or continuities depending upon which perspective one might take (Aporta, et al., 2018).

Figure 2 © Nataly Nemkova & Penny Fyta

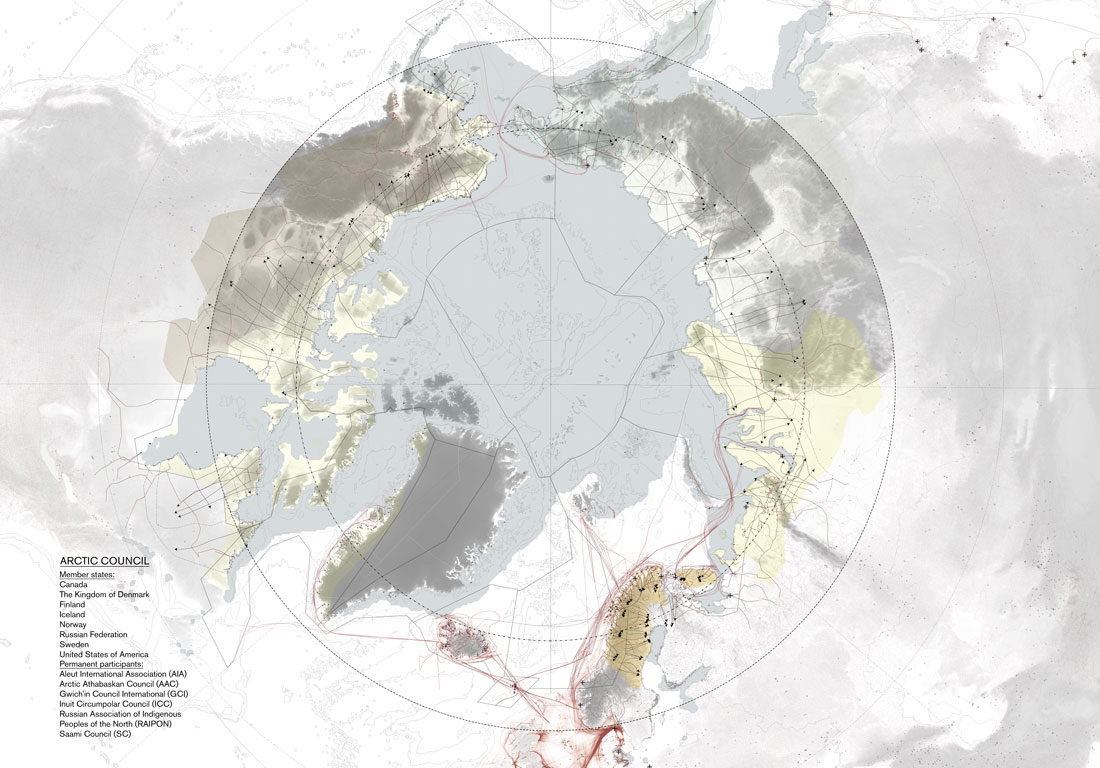

The atlas put forward by Nemkova and Fyta encompasses questions regarding how to deal with emergent year-round or new seasonal sea routes (and the port infrastructures required to exploit them), the migratory flows of caribou or reindeer herding and the nomadic livelihoods of indigenous people, plus the conflicts between nation-states claiming rights to resources. Attracted by previously ice-bound resources, new transport infrastructure, including large strategic ports, is being rapidly projected and constructed in preparation for the ice melting. This epochal shift in fortunes might eclipse the Suez Canal route between Europe and Asia, opening new trade routes. Similar to the Panama Canal, the new arctic shipping routes are examples of ‘material outcome[s] of […] globalisation’ (Sigler, 2014, p. 887). Despite playing a decisive role in globalisation and the supposed liquidation or ‘liquefaction’ of borders, nation-states with stakes in the region are now poised to fix borders and secure the control of these transport routes and the attendant natural resources. States are represented in the atlas by linear borders, while the nomadic indigenous people are represented by dynamic arrows, spatialising the Arctic Council’s member states and ‘participants.’ Founded in 1996, membership in the Council includes: Canada; Denmark; Finland; Iceland; Norway; Russia; Sweden; and the United States.

Since they were never ‘cartographically authorised’ in maps of the region and did not practice ‘(nation-)state territory’ (Elden, Forthcoming), indigenous populations who have inhabited the Arctic Circle for thousands of years do not have territorial rights. Ice melting and a new wave of Western colonisation are deeply affecting their seasonal and nomadic livelihood and their relationship to nature and water in its various states, especially ice. Indigenous nomadic inhabitants have been assimilated into the Arctic Council as consultation ‘participants’ to claim their ‘territorial rights,’ but what does this mean? If we understand territory in Elden’s terms as a practice, historically and geographically specific, and if it is a Western relationship between place and power (i.e., a bundle of political technologies for the control and measurement of terrain and land) (Elden, 2010, p. 811), would not the question of territorial rights, or the granting of the same, constitute a form of colonisation in itself? To address the ongoing conflict of interests in the region on the grounds and terms of one of the mentalities involved seems to be a form of imposition rather than participation.

Two clashing mentalities, livelihoods, relations between place and power, ways of seeing the world and relating to nature, are embodied in the disputed borders and movement arrows, both geophysically mediated. Not to romanticise the primitivity of this state of things, these lands are nonetheless some of the last bastions on Earth more or less outside of or beyond Western territorial ambition. Notably, the process of transformation and assimilation has already begun with the marketing of reindeer and the use of GPS. The latter technology is quite telling because it is literally a Global Positioning System; a way of locating oneself in the world system. In this conflict, fading signs of what it means to think ‘outside territory’ can be glimpsed. However, territory is taken for granted or assumed as a natural condition in the negotiation. In this way, the territorial apparatus does not acknowledge the existence of other mentalities or relationships towards nature, making itself the only way and obscuring its existence. Our idea of territory is so ingrained, that we take it uncritically and we see its practices, such as the violent drawing of boundaries as the only way forward. Indigenous people are represented and measured with territorial political technologies: e.g., maps and GPS. In Elden’s words: Why is it we cannot think beyond or outside territory today; ‘relations between power and place that are not territorial?’ (2018, p. 218).

These territorial fixes are further challenged by the geophysical dynamism. Rapid ice melting processes and seasonal transformations alter conventional land-water distinctions on which some of the territorial assumptions rest, questioning our static understandings. As the ICE LAW project puts it (under Elden’s Territory subproject leadership): ‘What is the relationship between the standard land-water division of territorial regimes and the construction of state territory, and to what extent do emergent social systems based on recognition of more complex geophysical systems challenge modern notions of statehood?’ (Steinberg & Coddington, 2014).

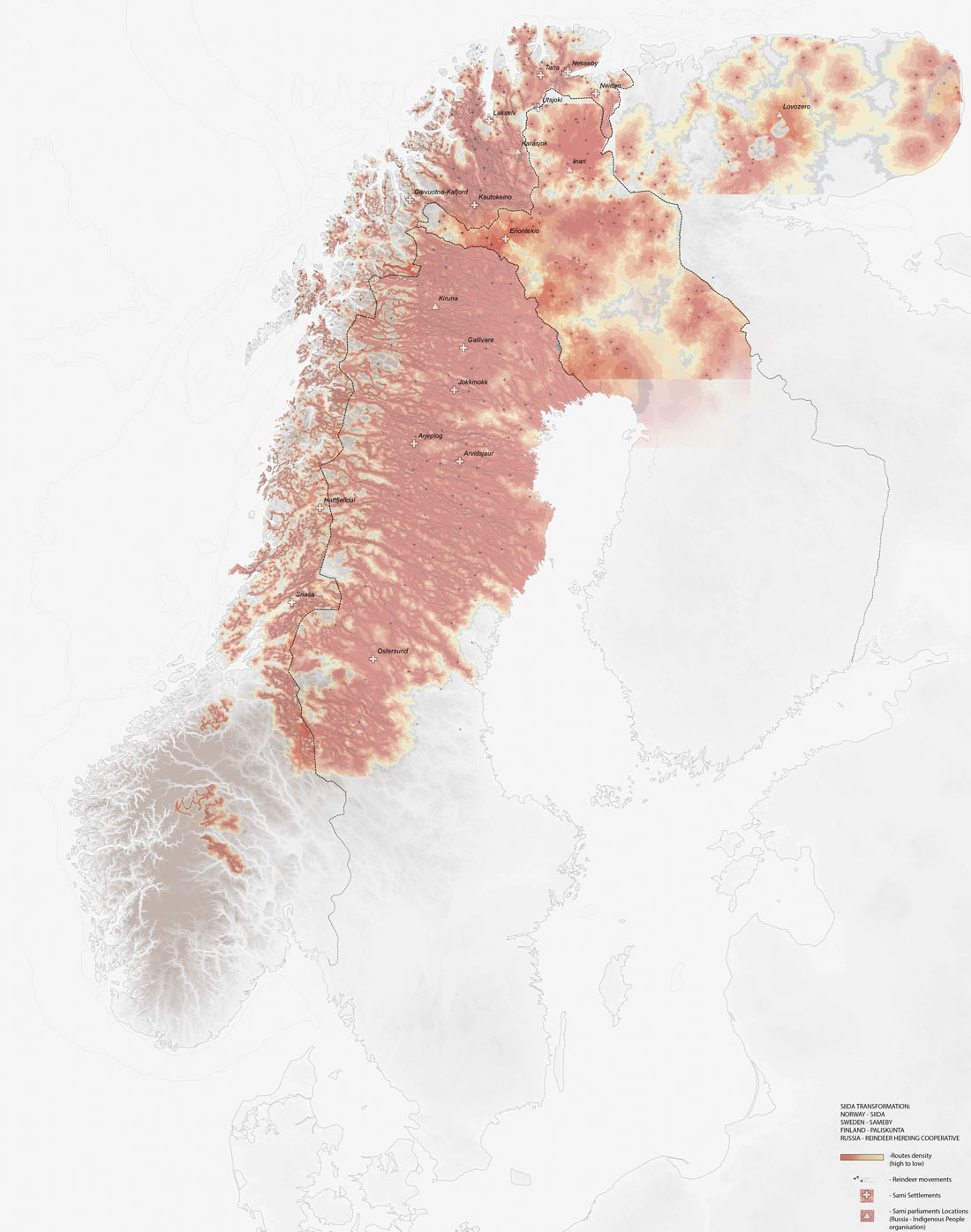

Figure 3: Clashing interests between reindeer movement and state borders. © Nataly Nemkova & Penny Fyta

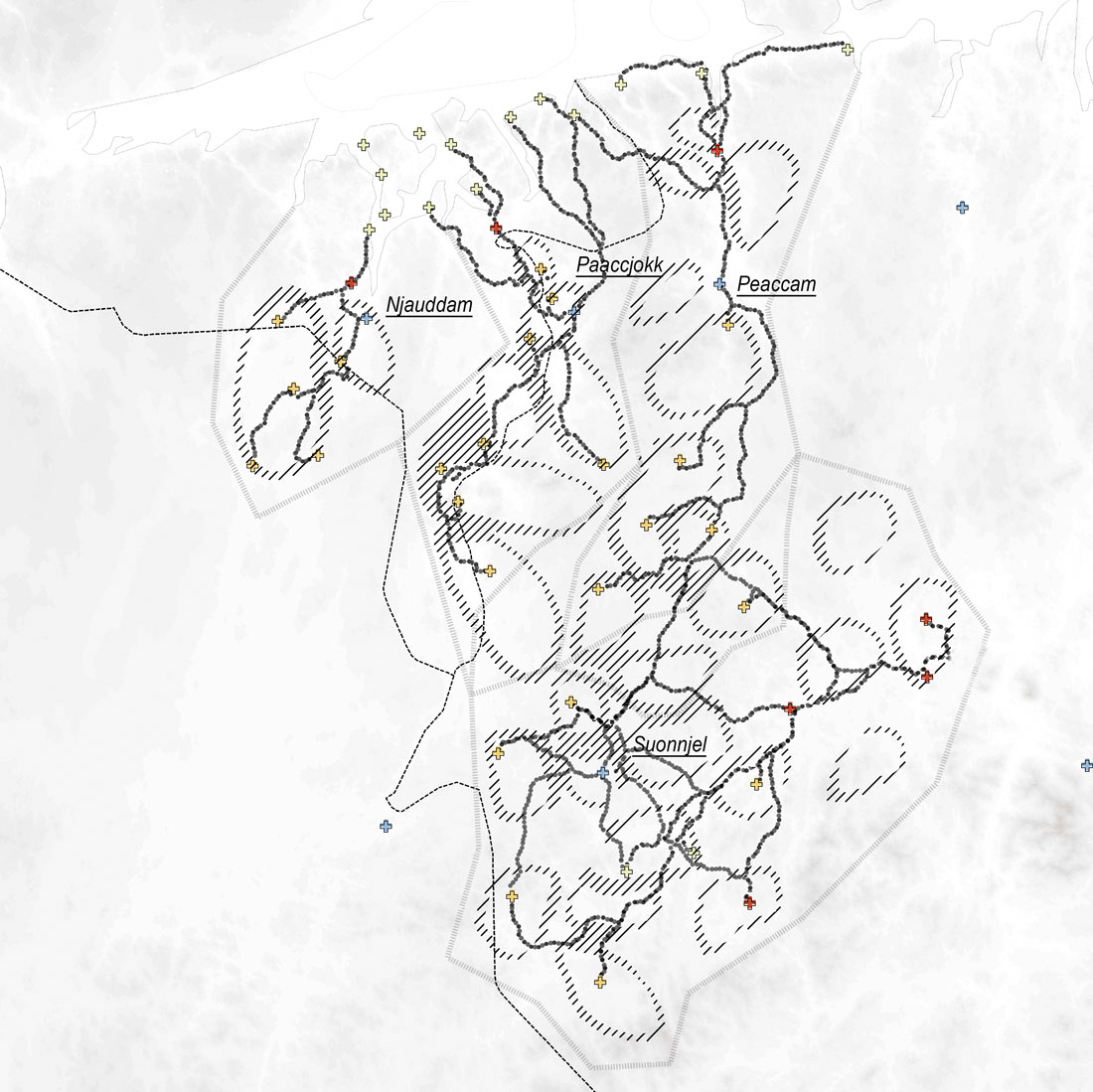

To explore these conflicting forms of power from the atlas, the project focuses on the Sámi people of Northern Europe. The country divisions of Norway, Finland, Sweden and Russia in Figure 3 overlap with their semi-nomadic way of life, which depends on trans-national reindeer herding, calving, breeding and grazing areas. The movements of their Siida organisations, a group consisting of several families and common lands (Nemkova & Fyta, 2015-16, p. 32), intersect with and overrun national borders. Transcending borders, their knowledge of reindeer,[1] their understanding of the Earth’s surface properties and their relationship towards nature [2] conflict with normative Western mentalities. Figure 4 and the maps from artist Nils-Aslak Valkeapää [3] offer an alternative vision to territorial thinking to claim different rights. This historical ‘map’ of the Skolt Siidas attempts to diagram – with Western cartographic tools – seasonal settlements, movement, common areas and the super-imposition of state borders in the 19th century (Mustonen & Jones, 2015).

Figure 4: Family distributions in Skolt Siidas. Re-drawn from Mustonen and Jones (2015).

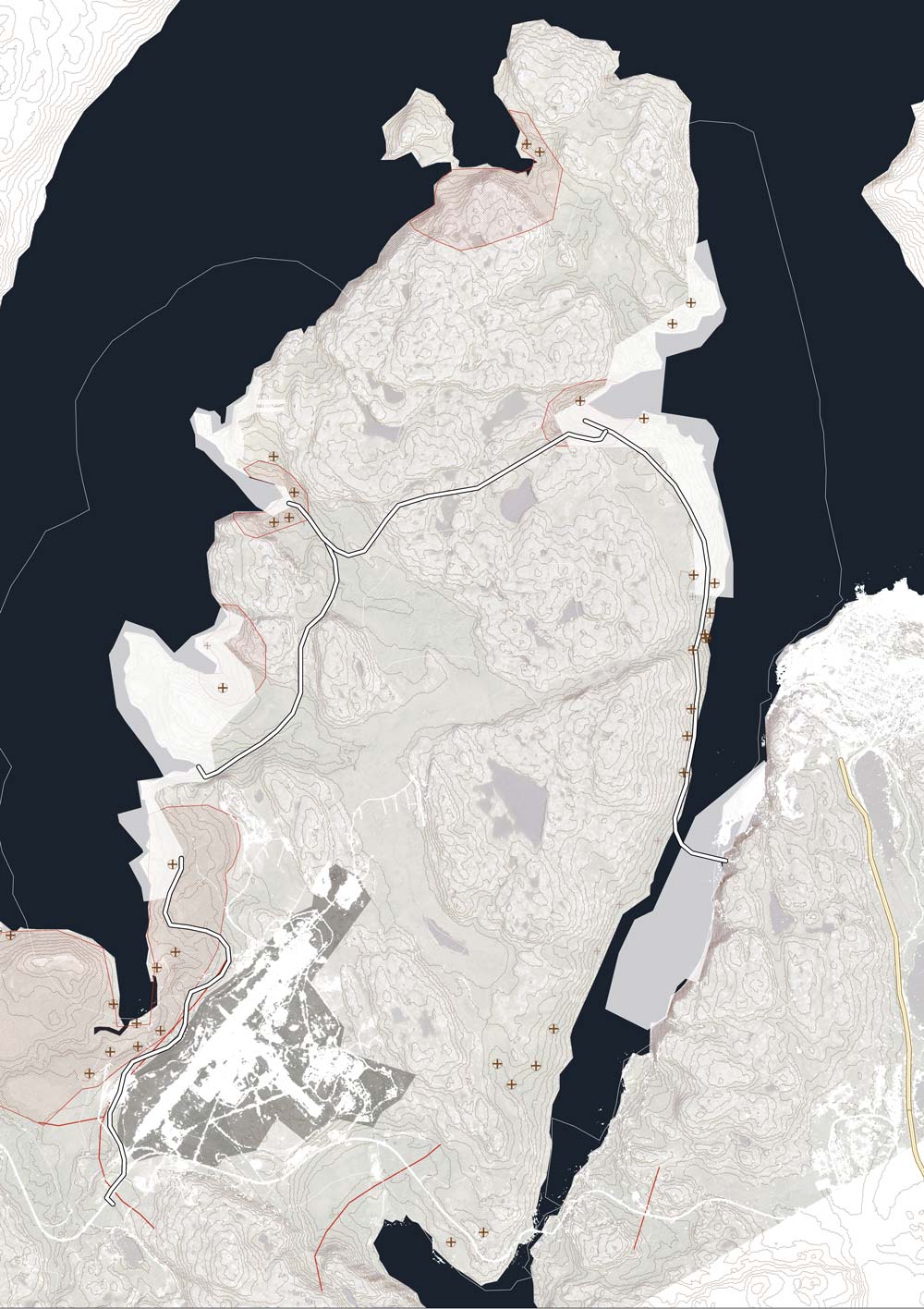

In the multi-scalar conflict, Nemkova and Fyta focus on the peninsula of Tommeneset, where four new ports – a form of infrastructural re-territorialisation (Introduction) – are planned to support the Barents Sea oil exploitation near Kirkenes (Figure 5). This strategic point, connecting land and sea, houses military activities in summer, tourism in winter and an airport, together with two Siidas in summer and winter (Nemkova & Fyta, 2015-16, p. 58). The project thesis explores the seasonality and the mutual effects of these activities, conditioned by the geophysical states of water. These include a simulation of reindeer flows, movement corridors and feeding areas.

Figure 5: Four new ports planned in Tommerneset Peninsula. © Nataly Nemkova & Penny Fyta

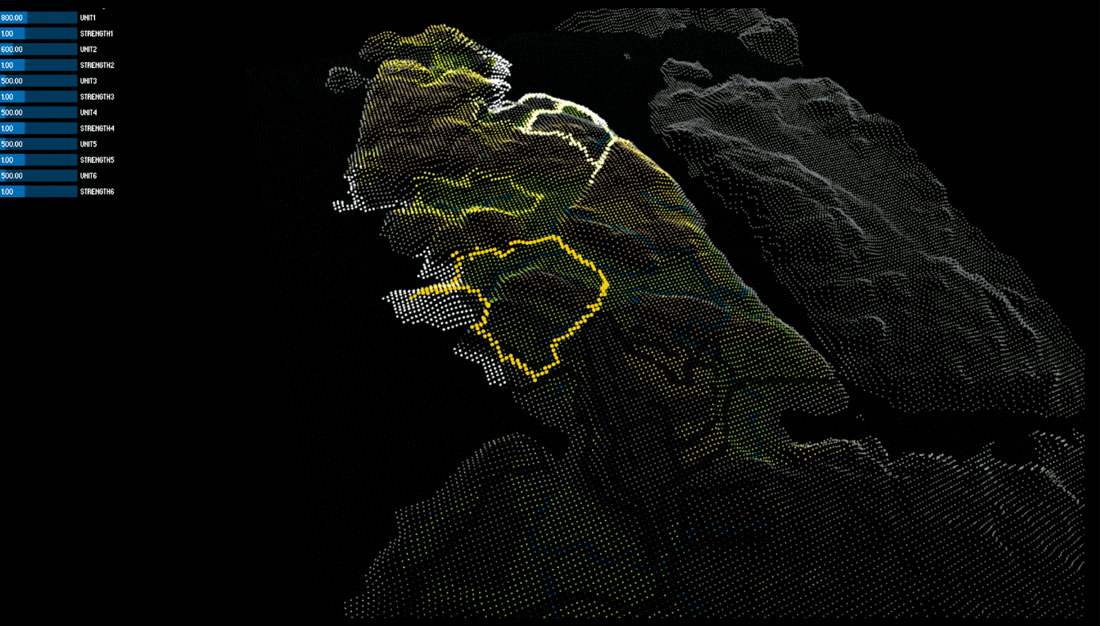

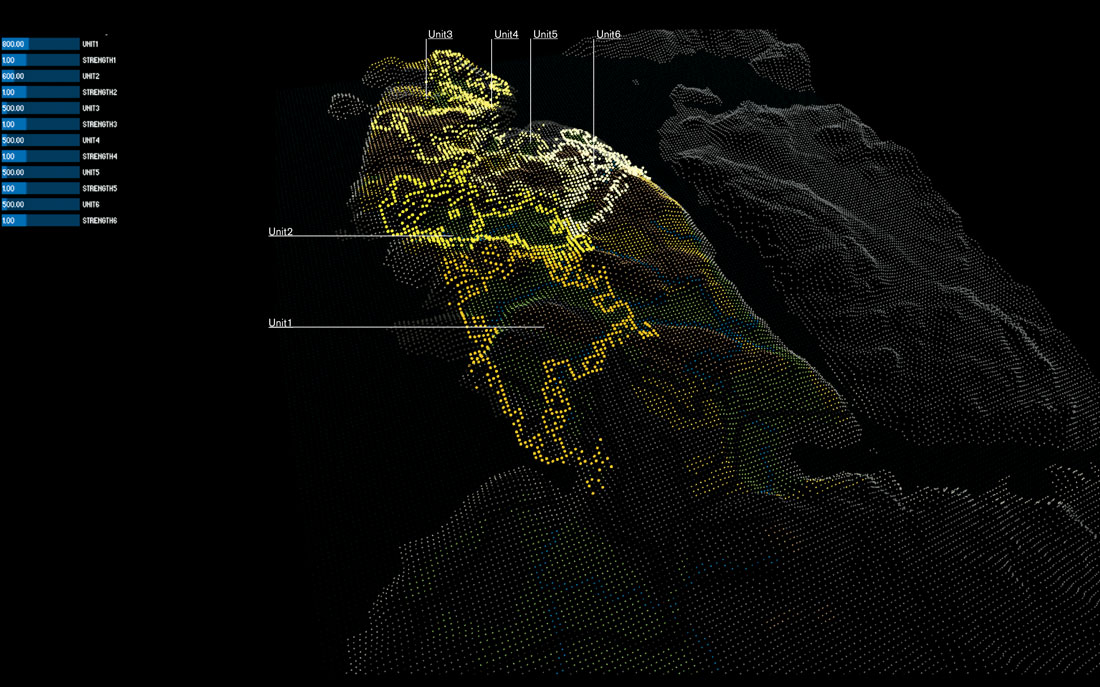

To negotiate the conflicts among the various interests, the project authors propose a tool where the border areas are shifted, according to time, seasons and physical conditions, challenging fixed land rights. It is interesting to note that to understand the complex and subtle material conditions, this tool is sketched and manipulated in a physical model where movable and stretching borders are woven and re-deployed through time (Figure 6), emphasising the materiality and volumetry of this terrain. The growing and shrinking of border widths varies according to reindeer landscape features. This mechanism is then translated into a series of digital policies that, according to the authors, show the consequences of decision-making processes and the shifting of the conflicting interests. This tool attempts to propose an alternative to conventional management – and to some extent Western thought – influenced by Siida rights, land share and flexible boundaries.

Figure 6: Physical model of the peninsula to articulate the conflicting borders according to the physical terrain. © Nataly Nemkova & Penny Fyta

In the tool, six family units are identified. With the introduction of the ports, the borders start shifting pixel units according to landscape and topography. Land is intentionally not shown as a bounded area. More intricate borders distribute the activities, reserving land for winter and harsher situations, according to the authors. The tool also controls the regeneration of areas by restricting some movements to prevent overgrazing. Where the areas start overlapping, common land is defined to be shared. The proposal also includes a reconsideration of port infrastructure so that it can shrink and shift with the decrease of seasonal activity. Road infrastructure is also designed to ameliorate their impacts and disturbances with vegetation, topography or land bridges. The negotiation is based on a series of regulations that shift borders if new infrastructure is introduced. It implies the re-thinking and constraints of each of the agendas. In turn, this produces various scenarios, contingent on the decision-making of intersecting interests and mediated by designed regulations. When necessary, the borders are materialised through wooden fences that serve as living and productive support for Sámi herding. These measures also include both corrals and tourism cabins, as detailed in the thesis booklet.

The promise of agency distribution

The challenge in this project is not so much to give a solution to the conflict, but, instead, to design the mechanisms that can challenge the Western concept and practice of territory to create the instruments where Sámi rights are acknowledged based on alternative customs. This is not so much about negotiating land, because that would presuppose the terms of the conflict, but two ways of understanding the relationship between place and power, between society and nature; two ways of representing and navigating it. As Sara claims, ‘(t)he recent legal acknowledgement of Siida must imply self-management based on Siida land rights, customs, traditions, and autonomous processes of knowledge’ (Sara, 2009, p. 176). For example, attempting to produce a map of Sámi livelihood is in itself a form of imposition, cartography being ‘actively complicit in the production of territories’ (Elden, 2010, p. 809); but, at the least, the very attempt makes us re-think political technologies of territory such as the practice of cartography and the production of knowledge.

To account for the clashing mentalities, the complex temporalities and dynamic materiality, the thesis proposes an interactive tool as a design mechanism. Its purpose is to simulate, visualise and understand the intricate consequences of shifting and re-designing borders; but it is important to question the forms of interactive participation that are offered to Sámi [4] and the grounds on which their agency is understood. Up to now, the questions raised by this project would fit better in the first section of this book on territory. However, these interrogations bring us back to the question of how overlapping forms of agency become operative in the design of the interaction of conflicting agendas and interests. In turn, this foregrounds the role of the designer and the forms of control behind the seemingly genuine and egalitarian participatory tools.

Figure 7: Tommerneset Peninsula interactive shifting borders tool. © Nataly Nemkova & Penny Fyta

Interactive distributions of agency and relational agencies are often cloaked in an inclusive and ‘vaguely egalitarian fashion’ (Malm, 2018, p. 1430) or with a design morality of apparent humility, where the designers’ reflective capacity (Spencer, Chapter 11) is held back for more equitable forms of agency – including that of objects. This needs to be openly addressed and ‘re-politicised.’ [5] Otherwise, the participation process risks becoming a path to renouncing human agency for that of computer systems – or whoever controls them – due, in part, to human slowness to calculate [6] the required complexity. These design mechanisms promise a democratic participation in the complex overlapping of the interested parties. But to do so, they require the design of a simplified comprehensible image of ‘interactive parametrics’ whose scenarios can be controlled by the user through the ‘graphic-user interface.’ This implies that a ‘political iconography’ (pace Pias words, and apropos of simulations) is necessary for participants to get involved. Inevitably ‘subordinated […] to the hegemony of images,’ [7] states Pias, the simulation entails the artifice of the – often interpreted and simplified – interactive mechanism.

Here, the designer’s agency rests not only on the articulation of interests according to bordershifting policies that arbitrate potential scenarios, but on the design of an ‘interface’ image for user participation to take place. The interface simplifies the calculation of complex interrelationships to support negotiations; but if this visual mediation is not critically acknowledged, participation is veiled and given up to the systems’ design and obscured power hierarchies. This is not to dismiss the relevance of thinking or developing alternative territorial technologies but to acknowledge the artifice of interactive policies, putting them forward politically ‘so that certain social and political values do not succeed in closing controversy in a way that is invisible to society.’ [8] ‘User-driven’ political technologies to measure and control land and terrain can be interpreted as a participatory re-branding of territory’s powers, but can this approach critically address the idea of territory from within its practices or ‘outside territory’ (Elden, 2018, p. 218)?