Liam Young calls himself an “architectural storyteller.” He uses fiction and film to explore visions of the future that amplify trends and technologies already present, challenging viewers to confront a not-so-distant reality. Young, who often collaborates with science fiction writers, technologists, and urbanists, casts a wide net: In addition to his London-based think tank Tomorrow’s Thoughts Today (cofounded with urbanist Darryl Chen), he helps run Unknown Fields Division, a roving global research studio that scours little-explored parts of the world for hints of future technologies and alternative narratives, and helms SCI-Arc’s Master of Arts in Fiction and Entertainment program. AN asked Young about his practice, his recent films, and the power of storytelling.

The Architect’s Newspaper: Let’s start by talking about Tomorrow’s Storeys, the film you produced for the Documenta exhibition in Athens this year.

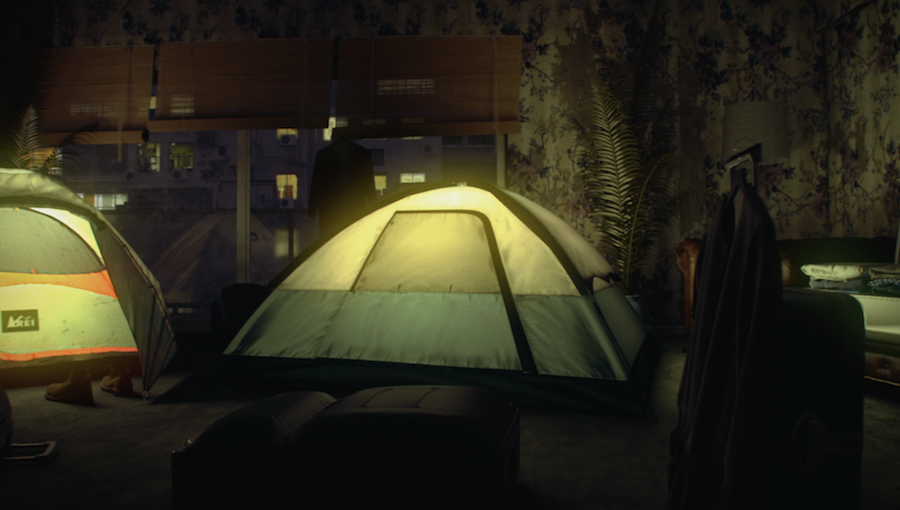

Liam Young: Basically, the setup is that the evolution of Airbnb and other smart city systems has created a condition where ownership as we know it has been totally rewritten and we now just lease a full area or volume. It’s an animated film where you drift through a building, eavesdropping on conversations that were written as part of a public futurist think tank. The Athens apartment blocks [in the film] are based on the dominant building form in Athens, this housing block that’s almost conceived like Corbusier’s Dom-Ino: a concrete frame with flat slabs that are infilled across time. The film imagines a fleet of builder bots that remake, demolish, and build partition spaces and volumes as they are required. So you no longer own a piece of property, you just own volume—but that volume might shift or reform itself at any time as needed. So cities are remade based on networking technology.

Still from “Tomorrow’s Storeys” (Courtesy Liam Young)

And what’s the premise of your film that’s premiering at the Seoul Biennale of Architecture and Urbanism?

It is an abstract, non-narrative sequence of vignettes, fragments, and moments of a future Seoul, a city in which all of the hopes and dreams, fears and wonders of emerging technologies have come true. Scenes of contemporary Seoul are overlaid with seamless visual effects depicting a world where the sky is filled with drones, cars are driverless, the street is draped in augmented reality, and everyone is connected to everything. It is narrated by the disembodied voice of the city’s operating system, who tells us its story and how it produces and manages the environments we will soon all occupy.

Right now, it seems like tech companies are really driving the development of smart cities like the ones you depict. But what role do—or should—architects play?

The issue is that, for the most part, these technologies have supplanted the traditional forces that define and shape cities. The [digital] network is now a more significant infrastructure for affecting change within a city than physical public space or traditional infrastructures like road networks and water grids. So the role of architects and urbanists is rapidly diminishing. We’re interested in exploring where new forms of agency for the architect might exist when so much of what defines cities is being outsourced to large-scale tech companies.

The role of the storyteller is certainly one that I’ve kind of fashioned myself around. However, I think it goes deeper. I’m looking at [technologies that] have evolved faster than our cultural capacity to understand what they mean or what they might do. In that sense, it’s really important to imagine the implications of these technologies before they’re actually implemented. We try to explore the role of the architect as a speculator, as someone who can prototype those implications in visual and spatial mediums.

Still from “In the Robot Skies” (Courtesy Liam Young)

Take something like driverless car technology. A number of architecture studios are asking, “What happens to a city when the driverless car comes into being?” The problem is that car companies have already spent billions and billions of dollars developing this technology. They’ve invested so much in it that this future is going to happen whether we want it or not. [Architects] should have been running these design studios, we should have been involved in the planning meetings of Ford and General Motors ten years ago, but we weren’t. For the most part we sat by idly waiting for it to happen. If we were in those rooms $15 billion ago, we actually might have been able to make a difference in the way that these car companies are thinking.

I think that’s one of the urgent projects of our current generation of designers: To tackle imminent tech, play it out in multiple scenarios that explore desired consequences as well as unintended consequences, then feed those stories back to a general public and to the tech companies that are developing them so that we can make more informed choices about the future we want to have.

What about the traditional role of architects, even in just advocating for housing or basic infrastructure?

I don’t think the necessity for architects, as we traditionally define ourselves, is going to cease to exist. There are still going to be architects designing houses and talking about space as service infrastructure, but the role of those architects is going to fundamentally change or it’s going to rapidly diminish. I’m not advocating for the total dissolution of traditional architecture; I can’t claim that every architect should be a storyteller, but some of us need to do that in more systematic ways than we currently do.

Still from “Where The City Can’t See” (Courtesy Liam Young)

Your film Where the City Can’t See presented a way for people to use technology to fight back—become hackers. Smart city technology is usually very top-down: even when tech companies are supposedly giving you choices, those choices inevitably benefit their business model.

That’s essentially what we are focusing on at the moment: the way that technology generates new forms of subculture. These technologies become the most interesting when they’re no longer in the hands of the companies that developed them, but when they get democratized and people start inventing their own uses for things, and we start seeing the unintended consequences of these technologies. That’s when they become really exciting.

[Another] big part of our practice is talking about the consequences of smart technologies. In order for everyone in a first-world city like New York to be running around on the latest smartphone, a whole lot of kids in Africa are going down the bottom of a mine with a gun to their head to dig out rare-earth minerals needed to make that smartphone. It’s no longer sufficient to describe those contexts as being pre-technology or pre-urban, because they’re part of an urban system, they’re part of the supply chain that produces the smart city.

So the people on the other end of the fiber-optic cable, they don’t have the latest smartphone, they’re not hooked into Nest adjusting the thermostat in their homes or uploading their data to the cloud, but they’re a consequence of the system that generates all those things for us in New York. We’re trying to tell these different kinds of stories, which all are part of the smart city—just not the smart city where we choose to point the marketing lens.