Throughout history, cities have often been compared with living organisms. The analogy between the city and the human body has been explored in depth by figures as varied as Plato, Vitruvius or Leonardo DaVinci. Urban tissue, a city’s heart, arteries and lungs are some of the terms that comprise the extensive urban planning vocabulary that has been created by comparing fragments of the city with organs or elements of the human anatomy. While the human body has served as a recurring metaphor to describe the complex functioning of cities, sickness has often been the allegory used to illustrate urban dysfunction. Above and beyond anthropomorphic conceptions of the city, statements like “Paris is sick”, proclaimed by Le Corbusier [1] in 1929, or Frank Lloyd Wright’s comparison, from 1958, between the cross-section of any city plan and the section of a fibrous tumor, [2] highlight the city’s metaphorical capacity to fall ill. “Sickness”, in this context, is not understood as intrinsic to the natural functioning of any organism, but rather as an evil that must be combated.

Le Corbusier, Frank Lloyd Wright, and many other architects and urban planners at the time, compared traditional cities with sick organisms in order to justify the need for undertaking large-scale urban interventions in keeping with the historic moment they were living through, thus promoting the functionalist utopia of the modern city. In many cases, an incomplete diagnosis of urban pathologies was used to argue the need to apply drastic therapies, which consisted in amputating affected tissues and substituting them for entirely new ones. The striking image of Le Corbusier’s Plan Voisin for the center of Paris perfectly summarized how a new “artificial organ” was implanted onto an amputated fragment of the ailing city. At the time, this image became a provocative icon that represented part of the Modern Movement’s approach, which had a broad influence on numerous projects for urban renewal across Europe and America.

Acupuncture

In the 1970s and 1980s, serious questions emerged concerning the Modern movement’s model for urban planning and large-scale urban renewal in particular. The shocking image of the demolition of the enormous Pruitt-Igoe housing project, which was an icon of modern urban planning for the city of St. Louis, on March 16, 1972, became a powerful symbol, comparable with the image of Le Corbusier’s Plan Voisin from 1925. It represented the end of an era and a changing sensitivity toward how our cities should be regenerated. Charles Jencks referred to its demolition as “the day Modern architecture died,” [3] and at the end of the 70s and the beginning of the 80s a new way of understanding cities emerged, along with a new way of diagnosing their pathologies and implementing the proper therapy.

This new way of understanding urban regeneration catalyzed in Barcelona in the 1980s under the name Urban Acupuncture. Just as Le Corbusier’s famous black-and-white image of the Plan Voisin transmitted, in a precise yet closed-off manner, one way of understanding planning in the Modern movement, the term “urban acupuncture” became a powerful abstract metaphor to evoke numerous images and mental associations representing an alternative way of understanding urban planning. The term was coined and spread by a series of urban planners, architects and politicians who participated in Barcelona’s urban renewal in the 1980s, such as Oriol Bohigas, Manuel de Solà-Morales and Joan Busquets, among others, and was later used by many other professionals, including the Brazilian urban planner and mayor of Curitiba, Jaime Lerner, author of the book Acupuntura Urbana, published in 2003. [4]

From that point on, the term Urban Acupuncture has been incorporated into the urban planning vocabulary to describe strategies based on a series of independent interventions applied in the urban fabric that have a direct impact on their immediate surroundings, but since they are coordinated they also produce a larger-scale effect. Manuel de Solà-Morales highlighted the “strategic, systematic and interdependent” character of the term Urban Acupuncture, and emphasized that its field of action is what he called “the urban skin” or the “epidermis”, understood “as a rich, complex, and enormously influential membrane” that constitutes a system in itself. [5]

Public space is part of this “urban skin”, where most of the urban acupuncture strategies were developed in Barcelona, which focused on reinforcing the role of small squares, boulevards and parks as elements that articulate public life. In his book Barcelona: The Urban Evolution of a Compact City, Joan Busquets points to Oriol Bohigas as the originator of this strategy, which led to the creation of hundreds of interventions in the city’s public space during the 1980s, classified into four different types: inner-city parks, squares and gardens, parks with facilities, and urban axes. [6] As a result of these strategies and the subsequent urban plans to open the city to the sea for the 1992 Olympic Games, public space in Barcelona acquired international fame, highlighting the political importance of promoting a vibrant public space capable of activating public life, while serving as a symbol of urban quality.

Public Space

Three decades after the urban phenomenon of Barcelona in the 1980s, public space is again in the spotlight since, according to many sociologists and urban theorists, it is gradually becoming a lifeless space that is also losing its public role. Martin Pawley anticipated this phenomenon in the 1970s in his book The Private Future, where he maintained that, in our consumer society, “the decline of public life is both a result and cause of privatization.” [7] More recently, the sociologist Richard Sennett described dead public space as the space devoted to the circulation of vehicles and people, claiming that it has lost its character as a place to remain, arguing that “the erasure of alive public space contains an even more perverse idea – that of making space contingent upon motion… the public space is an area to move through, not to be in.” [8]

Different factors contribute to the spread of this phenomenon. On the one hand, new commercial tendencies based on the concentration of commercial activities in shopping centers and department stores, combined with the current rise in Internet sales, are causing the gradual disappearance of small shops along our streets and, therefore, the decline of street life. On the other hand, the development of new technologies and the Internet has led to the birth of new media and virtual social networks, as well as new kinds of leisure activities like videogames and in-home cinema, which have changed our social behavior. The direct repercussion has been that numerous group activities that were traditionally held in public space have moved into the private sphere, so that parks and public squares have lost part of their function as meeting places.

One of the consequences of the lack of use of public space is that it can sometimes result in a generalized perception of insecurity among citizens. This, in turn, creates a nocebo effect, making citizens afraid of using public space because they consider it to be dangerous, which in some cases can actually end up coming to pass. In other cases, although public space may still be used, it no longer operates as a collective space for sharing activities, or as a place to connect and meet new people. In short, public space’s tendency to lose its public function deactivates part of the city’s socializing capability, which is especially important in an era that is characterized by a steady rise in cultural diversity among the inhabitants of our medium-sized and large cities. Public space, as a setting for cohabitation, contributes to teaching citizens to be tolerant with the unknown. On the contrary, the loss of its public facet can erode social cohesion and urban cohabitation.

Although the pragmatic vision of certain theorists and professionals defends that this change in the role of public space is part of the inevitable natural evolution of our contemporary society, many others have warned about the negative consequences that these changes can generate in our cities. The sociologist Zygmunt Bauman defends the fundamental role played by public space as a regulator of social relations with the phrase: “Public places are the very spots where the future of urban life (and given that the growing majority of the planetary population is made up of urban dwellers, also the future of planetary cohabitation) is being at this very moment decided”. [9]

With more than half of humanity living in cities and growth predictions for a worldwide urban population of 70% by 2050, Bauman directs our attention toward the importance of the role of public places, among them public space, for urban cohabitation and alerts us to the transcendence of our present moment. But, what role can public space really play today in reviving urban life? How can public space effectively contribute to improving cohabitation among citizens? And lastly, what kind of mechanisms or tools can be used to achieve these aims in the present?

Acupuncture + Public Space = Public Space Acupuncture

The growing awareness of the importance of public space as a regulator of urban cohabitation has led some cities to look for new ways of understanding its creation, design and management according to what might be called public space acupuncture strategies, born from applying urban acupuncture strategies exclusively to the sphere of public space.

Public space acupuncture is defined as a set of urban strategies applied exclusively to public space based on independent and catalytic interventions that can be realized in a relatively short period of time. These interventions are not only capable of creating a direct positive impact on their immediate surroundings, but even more importantly, they are also coordinated with the aim of activating the use of public space on a larger scale and of balancing, revitalizing or renewing urban life.

Although, as Milan Kundera said, “metaphors are dangerous”, the simile that compares acupuncture with a strategy applied to public space helps to understand an alternative approach that is based on a greater sensitivity in terms of the analysis of symptoms and the diagnostic methods used. To that end, it is important to take into account all kinds of urban and social symptoms that indicate a deterioration of urban life, such as a lack of use of public space, a large presence of run-down vacant lots, high crime rates, widespread unemployment, social segregation or a socially excluded immigrant population. However, it is also important to detect positive symptoms, weak as they may be, of urban activity, such as the areas in public space that receive the most use and where citizen interaction is greatest, the common ground among different social groups, and the collective or public activities that have the potential to be enhanced.

The metaphor of acupuncture as urban therapy in public space also suggests using solutions that stimulate or complement existing urban activity, avoiding drastic or traumatic changes. The city, like the human body, has its own defense mechanisms, and sickness can be understood as a mere imbalance so that therapy is only an aid to recover the lost equilibrium. This approach leads to minimizing each action, working on the existing foundation and devising new ways of solving problems that do not necessarily need to be based on permanent physical interventions in public space, but that can also consist of temporary interventions, or even actions without any physical component.

As a part of traditional Chinese medicine, acupuncture is also a thousand-year old practice of preventive medicine. Paradoxically, in antiquity, when Chinese doctors applied this practice, they only charged for keeping their patients healthy and received no pay if their patients fell ill, which also represented a serious loss of prestige for the doctor. The term “preventive” is destined to take on greater importance in present-day urban planning, especially in urban contexts where an increase in social instability has already been detected, in neighborhoods with large, socially excluded immigrant populations, in city centers where public life is disappearing from the streets, accompanied by a rise in urban insecurity, or in new urban developments where there is a lack of social cohesion.

Public space acupuncture is an especially useful tool in contexts that have been affected by economic recession in the wake of the global financial crisis. Given that many urban development projects funded with private capital, which could help revitalize our cities, have been halted and that it is also difficult to put through public initiatives because of the austerity measures that are in place in an attempt to reduce the public deficit, numerous city councils have been forced to look for new, low-cost or temporary strategies that have the ability to create a positive impact on the urban habitat.

In parallel, in recent years public space has also become a focal point for municipal authorities in many developing countries. The strong economic growth and rapid industrialization process that have taken place in many countries have given rise to migratory waves as workers have moved from the countryside into the city, leading to dramatic urban growth in a short period of time. These still-expanding cities are now assessing the quality of the recently created public space, as well as studying new strategies for supplementing and enriching it, to be implemented in coming years. The aim is to create a vibrant public space with a rich public life, which also prevents segregation, promotes citizen interaction and helps toward the development of social cohesion. Public space acupuncture strategies can be an effective working tool for this type of rapidly built urban structures because they can offer flexible and quick-effect solutions that can be adapted to any urban and social context.

On the other hand, both in the case of invertebrate cities characterized by a less visible nervous system of public space and in the case of generic cities where the design, program and quality of public space have not been considered a priority in urban planning, public space acupuncture strategies stand out as the ideal tool for helping to improve many aspects of urban life.

In conclusion, different kinds of strategies that could be classified as public space acupuncture have emerged in very different contexts. Despite the fact that, at the moment, these strategies are still in the pioneering stage and they tend to emerge as isolated actions, they share many common factors and could eventually constitute a new tool which municipal management bodies could use systematically. These initiatives might become a specific branch of urban planning in the future that would serve to complement traditional planning approaches, but which would have its own mechanisms for analysis, strategy development and process management.

Strategies of Public Space Acupuncture

The origin of the term “strategy” can be found in military discipline since its etymology goes back to “stratos”, the Greek word for army, and “agein”, which means leader or guide. Strategy, then, is defined as a set of actions that are systematically planned over time, which are undertaken to achieve a particular mission.

Based on this definition, it can be deduced that the word strategy implies a purpose. Public space acupuncture strategies don’t have an aesthetic purpose, such as beautifying public space, nor do they have a merely functional end, but rather they tend to respond to social needs or to the desire to improve specific aspects of urban life.

Systematic planning over time, which is implicitly associated with public space acupuncture strategies, suggests the possibility of an implementation by phases, as well as close monitoring of how the strategy evolves and the evaluation of the results obtained. This allows for the possibility of correcting the strategy during the process to achieve the desired goals in the end.

Each public space acupuncture strategy is made up of a set of actions or interventions that can be executed independently, but which are coordinated under a series of guidelines that dictate the precise place and the right time for each one to be carried out, so that all of them together can produce a broader effect than if they acted separately.

The term “strategy” suggests that there are generally a limited amount of resources available for achieving the desired objectives. That is why public space acupuncture strategies are sometimes, though not always, based on low-cost interventions that attempt to achieve maximum impact using a minimum of resources.

Different actors tend to intervene in public space acupuncture strategies, including politicians, municipal managers, urban planners, landscape architects, architects, artists, urban sociologists, citizens’ groups, residents’ associations and independent citizens. The strategies may be initiated by different entities, from municipalities opting for traditional top-down strategies, to citizens’ groups promoting bottom-up strategies, as well as all kinds of hybrid combinations between private entities and public bodies. A strategy that is understood as an open creative process provides a broad field for experimenting with a vast number of collaborative models, both in creating and developing the strategy and in its management.

Interventions

The term “intervention” designates the specific actions that make up the strategies. An intervention may have a temporary or a permanent character and it may be material or even immaterial. An intervention may consist in temporarily installing street furniture elements in existing public space, building a new square, organizing a resident participation day to plant community gardens, developing an artistic action, or even staging an event that invites residents to use public space on a massive scale. Sometimes, material interventions are combined with immaterial actions, and permanent interventions are combined with other temporary ones, generating an ample catalog of hybrid interventions.

In most cases, the interventions act on existing urban and social structures. Material interventions complement the existing public space with new additions that act as overlapping layers. These layers add new uses and meanings to public space, generating places for citizens to meet and interact that did not exist before. When the interventions are immaterial actions, they are applied to existing social relationships in order to reinforce them or to generate new, more complex and profound ties among people.

“Intervention” often implies an action that can be reversible, modifiable, expandable or repositionable. Working with the time factor, the intervention can acquire enormous versatility, becoming a temporary or ephemeral intervention, a test intervention, or even a mutating intervention with the ability to transform over time. This characteristic provides the strategy with immense flexibility, allowing for freer experimentation with the unknown, so that an unsuccessful intervention is not considered a failure if it provides a learning experience that allows for correcting the strategy in order to move forward toward the final objective.

Finally, the interventions can also be conceived as tools for experimenting with a variety of models for citizen participation during different parts of the process: in making decisions, in the design process or even in the tasks of realization and maintenance.

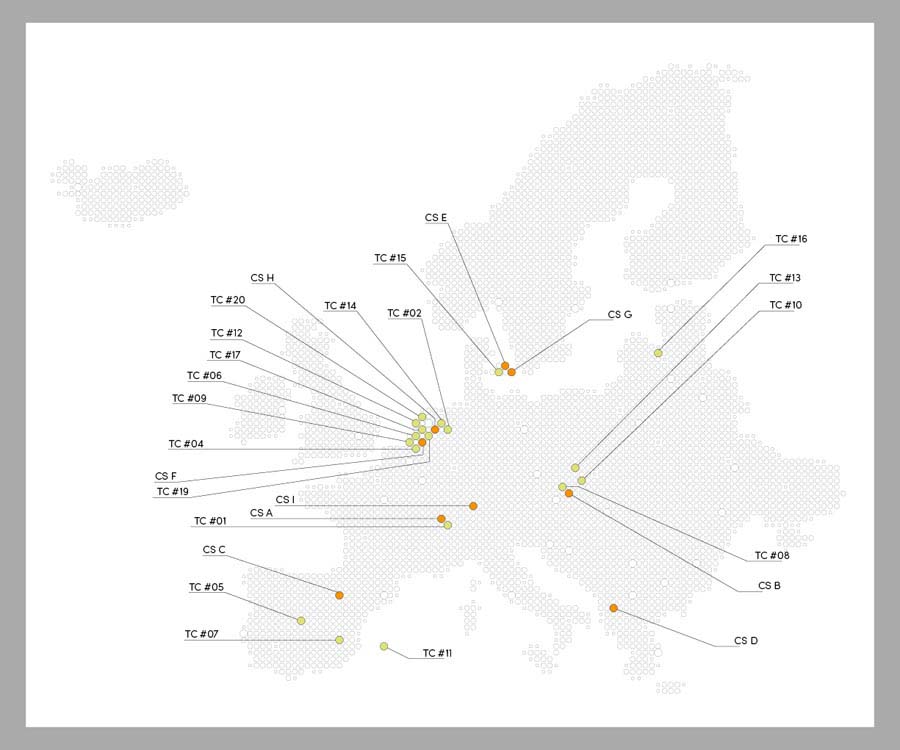

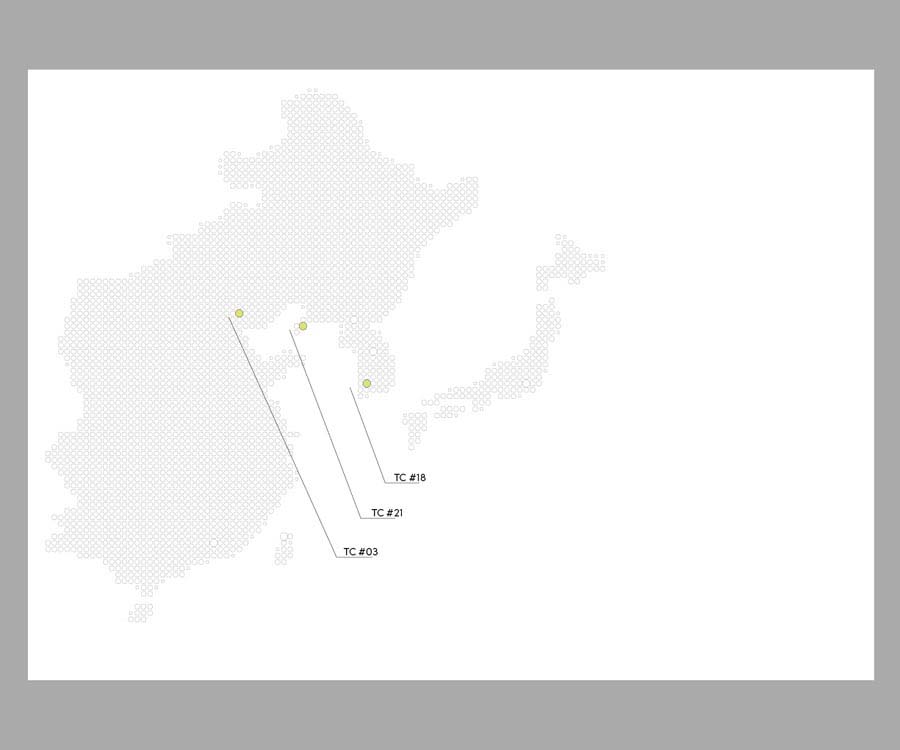

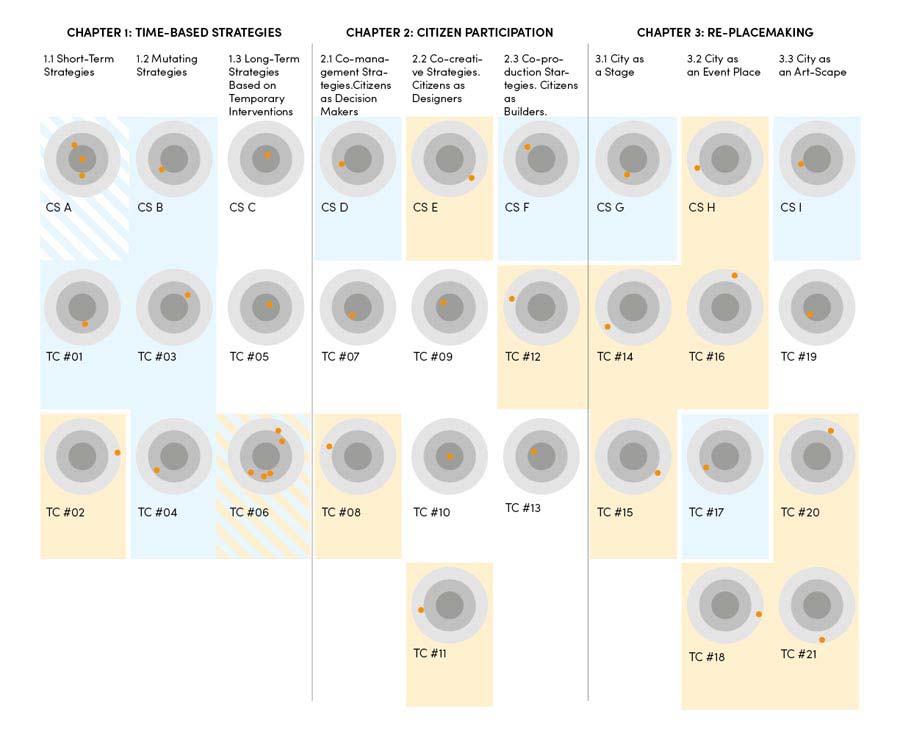

Public Space Acupuncture, the Publication

The publication Public Space Acupuncture analyzes nine case studies realized in eight European cities by different designers in collaboration with different stakeholders. Based on this analysis, nine strategies of public space acupuncture have been defined, which are grouped into three general categories: time-based strategies, citizen participation and re-placemaking. The characteristics of the different strategies and how they work are illustrated using 21 projects or test-cases developed by Casanova+Hernandez in collaboration with a number of municipalities, public and private clients, as well as universities and cultural institutions. In this way, the theoretical investigation is complemented with examples of its implementation in the fields of urban planning and landscape architecture, as well as with the diffusion of the built knowledge through educational activities and thematic lectures held at several universities and cultural institutions worldwide.