Even today, departing and arriving is no small deal when it comes to Iceland. It was quite a feat in the ninth century to even find the country, lying as it does hundreds of kilometres from anywhere across rough seas. The settlers nevertheless managed starting a whole new life and keeping contact with the civilization they left behind for a few centuries. In the early thirteenth century, internal conflict weakened Iceland and it eventually became subjugated to Norway, which in turn was united with Denmark. Colonized and poor the locals got pretty much isolated on that island for a long time. Iceland finally regained sovereignty after World War I, on 1 December 1918, and it was not to achieve full independence until 1944.

Hallgrímskirkja

Despite the distance, more people are visiting Iceland now than ever before. The number of tourists has increased from 493,000 in 2009 to 997,000 in year 2014. According to Arionbank’s estimates, 1,5 million are expected next year and 2 million in 2018 already. Until this newfound status as a “destination” arose, the biggest group of foreigners in Iceland at any one time were probably soldiers at the American military base in Keflavík. At the height of the Cold War there were almost 5,000 of them. The Icelanders, fearing too much foreign influence, imposed rules to limit mingling with the locals. At first, just 100 people were allowed to leave the base at a time – and only on Wednesdays: the one day in the week when the bars in the Reykjavík city centre were closed. Nevertheless, the post-war Allied military presence still had tremendous effect upon the built environment in Iceland: importing technologies, building airports and other infrastructures, and providing jobs – until the base was shut down in 2006.

Iceland T-Shirt

Of course there have been many other visitors to Iceland before and since. Some of them, such William Morris and W. H. Auden, even found the experience worth chronicling (in Icelandic Journals and the poem Journey to Iceland respectively). Likewise, we Icelanders like to travel abroad, not looting and pillaging like our Viking ancestors (although Icesave victims might think otherwise), but often just for holidays on warm beaches – like the hordes who visited the Costa del Sol for sangria parties in the 70s. We also travel for work and for higher education, options for which are limited on the island.

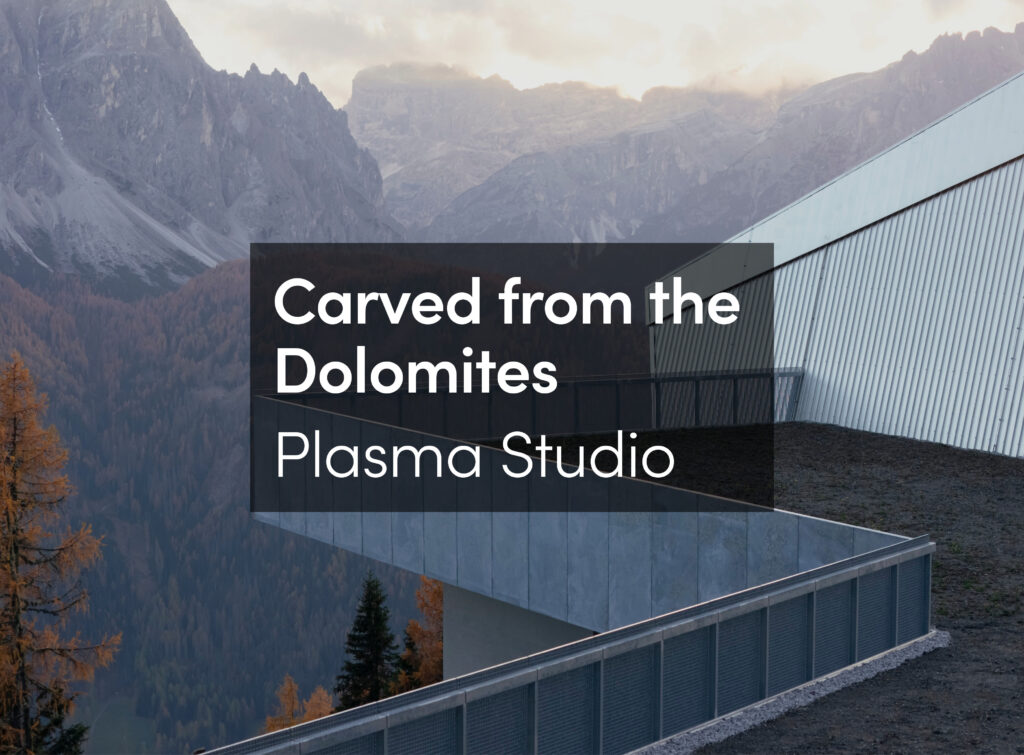

Recently I listened with interest to a Norwegian architect describing his first visit to Reykjavík and how he hadn’t appreciated it until he’d driven around the entire island, experiencing the way the buildings clung to the hillsides, turning their backs to the northern winds, engaging in just enough dialogue with each other – but not too much. Only then did Reykjavík start to make sense to him standing out as a special and fascinating type of urban fabric.

But that was before the building bubble, which led to financial meltdown in 2008, which in turn led to all the island’s banks having to be restructured from scratch. It was a boom fuelled by a finance sector pushing loans for expensive buildings and infrastructure, and shaped by 90s global dreams of cities competing to attract creative, mobile populations who would come to live in shiny new high-rises and pay to enjoy culture in slickly designed objects like the giant Harpa music hall. For Iceland’s modest population of just 350,000, this also meant the costly expansion of infrastructures, such as a new highway system in the Reykjavík capital area (pop: 200,000). For some reason there was a particular emphasis on clover-leaf interchanges – nine of them were built before the Ponzi scheme collapsed. In the parliament there were even discussions at one point about how the next (and most central) interchange should have at least three levels and demonstrate some serious spaghetti style. It was intended to make the arrival for visitors smooth and grand into a centre of gravity of what was planned to a new tax haven; a capital of global finance!

Remote, small communities like Iceland make perfect testing grounds for new fashions. Indeed clothing companies often try out new lines here a year or two before the global launch. Little did we know, we were not ahead of the world with the latest fashions – we were just guinea pigs, canaries in the coalmine… in finance acrobatics and development of the built environment alike.

The urban transformations of the noughties went hand in hand with a new influx of foreign nationals, though this didn’t play out entirely according to theory either. Instead of creative workers occupying sleek buildings, the new residents were mainly construction workers from the Baltic countries and Poland who came to participate in the boom and then chose to stay on despite the recession that followed the crash, albeit in less glamorous neighborhoods. Some ideas can be exchanged for others if they don’t work out, but newly built buildings tend to stay put. One of the remnants of the “global city” strategy that was already realized before the crash is a series of apartment towers by the waterfront hovering dozens of stories above the old(ish) low-rise city centre (only a handful of the buildings in the centre are more than 100 years old); blotting out the views to Esja mountain in the north.

As the crash fades into the past the “corporate subjects” (individuals or groups organized in holding companies) ; people who invest in domestic architecture, not to live in themselves, but for speculation and profit alone, so towers keep getting built. Judging by the level of public outcry many Icelanders, architects in particular, grieve for the loss of the character of the old city as they once knew it. Even if prerequisites have changed after the crash, obsolete masterplans set the premises for new ones because developers threaten with court action to secure compensation for their “theoretical” losses if the new plans are not as lucrative for their purpose to profit. The city’s lawyers advise local politicians against conducting a test case to attempt doing away with the repeated absurdity, so despite some helpless attempts from the city administration to negotiate a better deal for the community as a whole, the developers continue to more or less get their way.

The exceeding number of tourists is a special challenge in this context. Since 2005 the number of overnight stays by guests, increased by 146 per cent (up to 5.4 million in 2014 from 2.2 million). The city centre is rapidly being transformed into a hotel haven.Even if many existing buildings have regained a new life, others are being extended or suggested torn down in order to hike up the number of rentable square meters in new buildings. Currently, hotels are run in 15% of the building mass of the city centre and the city administration is planning to impose an unprecedented limit to maximum 23%. Hotels in the Reykjavík capital area are among those with the highest utilization ratios in the whole of Europe, or 87% on average.

Accommodation supplied by shared economy websites such as Airbnb, a popular option amongst tourists and backpackers alike, is also increasing sharply. It was estimated this June that some 4,100 private rooms in the capital were listed on such sites – the equivalent of all guesthouse and hotel rooms combined. This taken into account, some 4 per cent of all apartments in Reykjavík (compared to 0.4 per cent in Berlin), are rented out to tourists. Thanks to the publicity generated by recent natural and economic catastrophes it seems as if the whole world has found a comfortable and comparatively safe resting place in Icelandic living rooms.

Airbnb Logo

That occasional pedestrian alluded to earlier has now been replaced with lively hordes of selfie-stick-wielding travelers dressed in brightly colored outdoor clothing, drifting further and further across the delicate landscape of the island in search of the ever more exotic experience. Some locals see this as a sign that the world has finally realized how fantastic Reykjavik’s city centre is. You might say that was naïve, after all tourists are primarily coming to Iceland because of exotic landscapes and while organizing transport out of town they stay in the hotels in the centre, because that’s where the hotels are. In any case the claim is a bit of a contradiction when the city centre is starting feel more like a northerly version of Costa del Sol than old Reykjavík.

Spurred on by government branding campaigns, whoever wants to come to Iceland is courted and welcomed with open arms.

One would think that in principle it came down to a hope that any cash brought from outside can be used to pay off the debts, which are to a large extent rooted in the urban environment built up until the crash. And now that very same environment has to be expanded to house the tourists bringing the cash.

Even if the tourists make it easy for some to make profit, there are fundamental disadvantages for others. The municipality suffers because tourists represent little direct income for them, while infrastructural burdens like waste disposal increase. In addition the hotels stifle one of the main aims in its new masterplan, which is to house as many Reykjavíkians as possible as close to the centre as possible. The businesses profiting from overnight stays of tourists come at the expense of a desperately needed rental market. There is no way that ordinary local long-term tenants can compete with travelers paying by the night, and rental prices have increased over 29 per cent since 2011. This comes in addition to the speculation in residential space, triggering a real-estate bubble which has driven up the prices by 23 per cent in the same period.

The losers in this game are the young and those who came badly out of the financial crash in the first place. Despite tourism’s direct contribution GDP is close to 5%, many locals are embarking on yet another set of travels. They go to neighboring countries in order to work and earn enough to pay their mortgages back home. Meanwhile, the need for increased workforce in the tourist industry, 5.000 people in the next 3 years, is estimated to be fulfilled with guest workers from abroad.

Iceland has 7 times fewer refugees in relation to size of population than the average in the EU, a fact hardly having to do with geography only. The refugee policies and the way in which the American troops were displaced from the centre of Reykjavík stands in striking contrast to choice of urban strategy dealing with accommodating tourists. But it also reminds us on the former military base by Keflavík airport, which stands more or less empty. So are underexploited accommodation facilities many other places in the greater capital area which could be retrofitted for the purpose. Running hotels might work many places on the fringes, and they have the advantage of being very well connected to the surrounding nature. However, retrofitting housing into hotels on the fringe of Reykjavík would not work in because the recent masterplan doesn‘t allow that.

Alþingi

Alþingi

Considering the EE on the Reykjavík city centre, a large portion of the population and the sensitive ecology of Iceland (an urgent topic not discussed here) one wonders if alternative overarching strategies the have been considered.

Why chose to drastically change infrastructures to meet whatever demand turns up if it is not necessary? Examples from other scarcely populated alluring destinations could be helpful., The Kingdom of Bhutan, for instance, only allows a handful of heavily taxed tourists to enter at any given time, allegedly because the infrastructure can only support limited numbers and the cash harvested with the help of the tax is needed to expand it. While the Bhutan policy is based on the idea that gross national happiness is more important than gross national income, one could ask if the heavily indebted Iceland has come to the conclusion that it simply cannot afford not to do whatever might refill the coffers right away – no matter the long-term price.

The question is whose coffers are being filled. Your choice of host and produce you buy the next time you visit Iceland will decide.

Harpa

And when you are there and you look out from the city centre towards the old harbor, you will notice a rather unpleasant gaping hole in front of the most elaborate and well-proportioned façade of the the Harpa concert hall, designed by a world famous artist. Consider now exchanging the view of that Ólafur Elíasson façade from the same vantage point for a generic Marriot hotel and shopping mall, intended to cover 15.000.000.000.- ISK of the debts left behind from the construction of Harpa. Welcome to Iceland – enjoy the view!