I went to architecture school at a time when the periodic debates about the uses and the ethical qualities of modernism flared up. Our younger teachers taught us that modernism had failed. It had produced dysfunctional housing blocks in which the lower class was imprisoned. It had led to the creation of soulless office blocks. It had wiped out the beauty and mystery of the natural world. It was producing ugly objects and indecipherable messages. What was needed was a return to forms that were recognizable, scaled to the human body, and made out of natural materials. Though we accepted what our teachers wanted us to believe, we soon found that it was impossible to design things as they had been before industrialization. We could not give large-scale projects a human scale; we could not afford to use natural materials; and we could not ignore the technology and the landscape human beings had made in the last century, as it was all around us. We lived in a modern world, and had to act within it.

Robert Venturi, Vanna House, Chestnut Hill, 1963

As a result, many of us began looking back at what not our teachers but their teachers, and their teachers’ teachers, had done to try to give shape to the modern world. Was there a point at which modernism had gone wrong? Was there something about modernism that had led to inhuman constructions, or was it merely the direction modernism had taken in the latter half of the twentieth century that was at fault? As we were casting around for suitable images and forms, something strange happened: many young designers began to mine modernism. They self-consciously adapted the shapes, spaces, and images of early modernism in order to create a collage of possibilities with which they wanted to shape the modern world. Today, many of these designers who were avant-garde in the 19XXs are, in the tradition of modernism itself, successful practitioners who have reshaped modernism into a self-reflexive way of working and are producing buildings, objects, and images across the globe.

What is even more astonishing is that this neo-modernism is everywhere. You see it in everything from Apple products to W Hotels, from haute couture to Zara, and from Shanghai to Santiago. This knowing use of abstraction, clean lines, forms without decoration, and open, fluid spaces has by now has become the new normal, the little black dress of architecture and the default mode of design. Is modernism, after a brief defeat, finally triumphant? Are we seeing a celebration of the brave new world modernity has opened up for us, without guilt but with a critical consciousness? Or are we just living through the disappearance of modernism into a way of working and appearing that cannot be avoided, because it is embedded in how we build, how we work and play, and how things are made? Might that mass production of forms, spaces, and images without human affect be as destructive of humanity as our modern world has in many ways always been?

This book is a part of my attempt to figure out what modernism is and whether it is still viable or meaningful. It comes out of my engagement with architecture and design and my belief that we can and must act in a modern world, with a full realization of all the horrible mistakes that have been made in the very attempt to do so. I am still a convinced modernist, and this book attempts to show why.

The very terms I use to ask the questions above raise the question of what modernism is. I believe that question is easy to answer: modernism is the representation of modernity. Any attempt to give shape to, represent, express, or otherwise allow us to experience our modern world—or, more precisely, that which makes our world modern—I would call “modernism.”

This definition instantly begs the question, What is modernity? That is an altogether more difficult question. The earliest uses of the term “modern” date back to the twelfth century, when arguments first arose about whether you could invent something new, and whether that new poem, in this case, could be representative of the world the poet was living in, or whether his task was merely to copy and interpret the wisdom handed down over the ages. This long-simmering debate did not erupt in full force until the seventeenth century in the French quarrel between the ancients and the moderns. By then, the “modern” was the French, the innovative, and the reflection of contemporary language in theater, whereas the “ancient” was the dramatic tradition imported from Italy. An invisible boundary had been crossed, as the Italian tradition was itself a fairly recent import. That the making of a cultural artifact was a conscious choice between various modes of representation which in themselves stood for a host of political as well as aesthetic structures (native or foreign, different parts of the ruling class) meant that the “moderns” had won the argument: making a play was something a free individual did as a deliberate act, not as an automatic transcription of some unquestionable truth. Modernism had been born, and the modern world was the one both the writer and the viewer inhabited. It was the here and now.

Yet, modernism is not just a matter of what style you choose and in what manner you thus ally yourself with a particular movement. Nor is modernity merely the consciousness of being alive at a certain time and space. At its root, modernism is a question of having something to represent that is of the moment. In the most radical interpretation of the term, modernism always comes too late. The modern is that which is always new, which is to say, always changing and already old by the time it has appeared. Modernism is always a retrospective act, one of documenting or trying to catch what has already appeared—an attempt to fix life as it is being lived. Modernity is just the very fact that we as human beings are continually remaking the world around us through our actions, and are doing so consciously. Modernism is a monument to or memory of that act, which in its own making tries to remake the world it is pretending to represent.

These philosophical definitions, however, ignore an evident truth: something changed in our world at the end of the eighteenth century, accelerated in the nineteenth century, and completely altered all reality as we know it by the twentieth century. That thing was a combination of the so-called Industrial Revolution, real revolutions in France and the United States, discoveries in science, and large social movements that led to an explosion not only in the sheer size of the world’s population but also in its mobility. That movement of people and peoples, paralleled by the increasingly frenetic movement of goods and ideas, meant that our reality was increasingly in flux. You can–and many people continue to—argue about which of these phenomena came first, what was the underlying root cause, or what caused all others to appear. I will leave it to others to try to answer those questions. I will instead attempt to engage in a modernist act: to describe the particular reality of that phenomenon of modernization—exactly what kind of world, physical and around us every day, those forces produced. That leads to other questions. What exactly are the contours and what is the character of modernity as we can experience it as all around us, as a fact? How has it been made, by whom, and for what reason? How does it function?

You can ask these questions in an abstract manner, through numbers and statistics, or through narratives. For instance, economic developments and political actions certainly caused cities to appear, changed the nature of the spaces we inhabit, and led to the refashioning of vast territories. But I want to approach that apparent reality in another way: by looking at it as a continually evolving reality. I want to examine the images, forms, and spaces modernity has produced, and analyze the ways in which we have tried to give shape to them. I believe that this approach will allow us to begin to understand that modernity is what we make of it, how we find our way through it, and how we make ourselves at home in it. Modernism is a way of consciously making the modern world; a way of figuring it out in form, space, and image; and a way of transforming it into a container in which we feel we belong. Modernism thus can act in parallel to analytic attempts working within our modern world while at the same time constructing or reconstructing that world. It is, to misquote one architect, that which is always present at the same time that it represents.

The task of this book is to try to describe the phenomenon of modernism in the field of architecture and design, where conscious makers have tried to answer exactly those three questions of how we can find our way through, figure out, and be at home in the modern world. I would argue that they have done so in this particular field because of the impetus of something strange, a derived phenomenon that is difficult to define. Something new appeared to them, something called space, and the forming and representation of that space stood at the core of modernism in this field. Space was not place but its derivative, its forming, its representation. It was, like such other engines of modernization as the zero (which allowed for advanced mathematics as well as interest calculations), invisible, but crucial in making the world operative, productive, and usable. Like modernism itself, space had very old roots, but in the nineteenth century it suddenly took on a scale and presence that was startling to many observers. Its definition became the justification at the core of most modernist design.

This space was the natural habitat of the modern human being, a being that we would in economic terms call a middle-class individual. It was the middle class who stood at the core of the changes that made the world thoroughly modern, and modernism made that class at home in modernity. Further, I would argue that the tools for the production of the modern world—namely, technological artifacts—became the second arena in which modernist designers acted. They worked to utilize, house, contain, and represent that technology. Finally, the methods they used to understand, shape, and represent space and technology tended toward abstraction, the use of geometry, a tension between revealing and framing technology and space, and an attempt to extend that modern world through this abstraction, geometricization, revelation, and framing toward something postulated as perfect. In this, modernism is plastic–it molds and melds everything continually toward an unknowable purpose.

The Industrial Revolution and the political movements that paralleled it, as well as the developments in science and general thought, were led, or produced, by a particular class of people. These were men and women who were not dependent for their survival on agriculture, nor did they support themselves by controlling the work of those who did. They generally lived in cities, which were in themselves places made by humans and set apart from nature. You could argue that this class of humans inhabiting an artificial world and surviving by the manipulation of derived value (the finishing of goods, the trading of those goods) had existed since time immemorial. By the eighteenth century, at least, their numbers and the sophistication of their activities had reached a stage such that this class had a significant impact on the world around them. There is no one moment or occurrence that marks the emergence of the middle class, and you can find middle-class spaces far back in history. But there are moments when the middle class developed the power to control their environment at such a scale that urban places changed in a radical manner. The extension of Amsterdam through its semi-hexagonal rings of canals starting in 1613, at the same time that the first stock exchange appeared there, is certainly an early version of such a new kind of space. The space of the trading ship, an artificial community floating freely around the globe and moving people as well as goods and ideas, is another early prototype. The marketplace, an open square with temporary stalls made out of more or less mass-produced wooden elements that had a modular character, might be a third prototype.

All of these spaces shared characteristics. First, they had been made by human beings and had few, if any, traces of the nature they replaced or on which they floated. Second, many different technologies came together in their production;.they were constructed of elements that were modular and usually mass-produced. Third, they appeared as figures of abstract geometries that ordered and organized their various components. Fourth, there was something at their core that was difficult to define, but around which they existed: space. It was merely an empty place, one that allowed for trading, communication, and movement (such as the canals of Amsterdam), and that was free. It was what had always defined cities: the free space in which you were not bound by the rules of the land and its lords, a space that consisted of the streets, alleyways, and squares between the dwellings and churches, but also of the property in which you dwelled—or, more exactly, in the fact of property (one’s “proper” place) itself.

This space was the place of the middle class. If peasants lived on and were of the land in hovels that were of the earth, and princes lived off of and above the land in castles and palaces, the middle class lived exactly there—in the middle. They were on the ground, in the stores below the piano nobile (noble floor) where the aristocracy lived, crowded together below the castle, and yet outside of and separate from the land itself. They were in a space that they had made and continually remade to suit their lives. The middle class appeared in a space they could use, but where they could also appear as themselves.

The attempt to shape that space in a conscious manner began in most cases not through the agency of the middle class, but through the needs and the desires of the aristocracy. The first consciously designed open spaces that were left open, organized and paved, or ordered with surrounding gateways and facades so that they could be used and would have a clear frame, were made not by the middle class but by princes as parade grounds and by the church as places for ritual gathering. Streets that were straight and efficient were usually made for marching, not merchandise. Space was opened up from the top, clearing out the messy vitality of middle-class life.

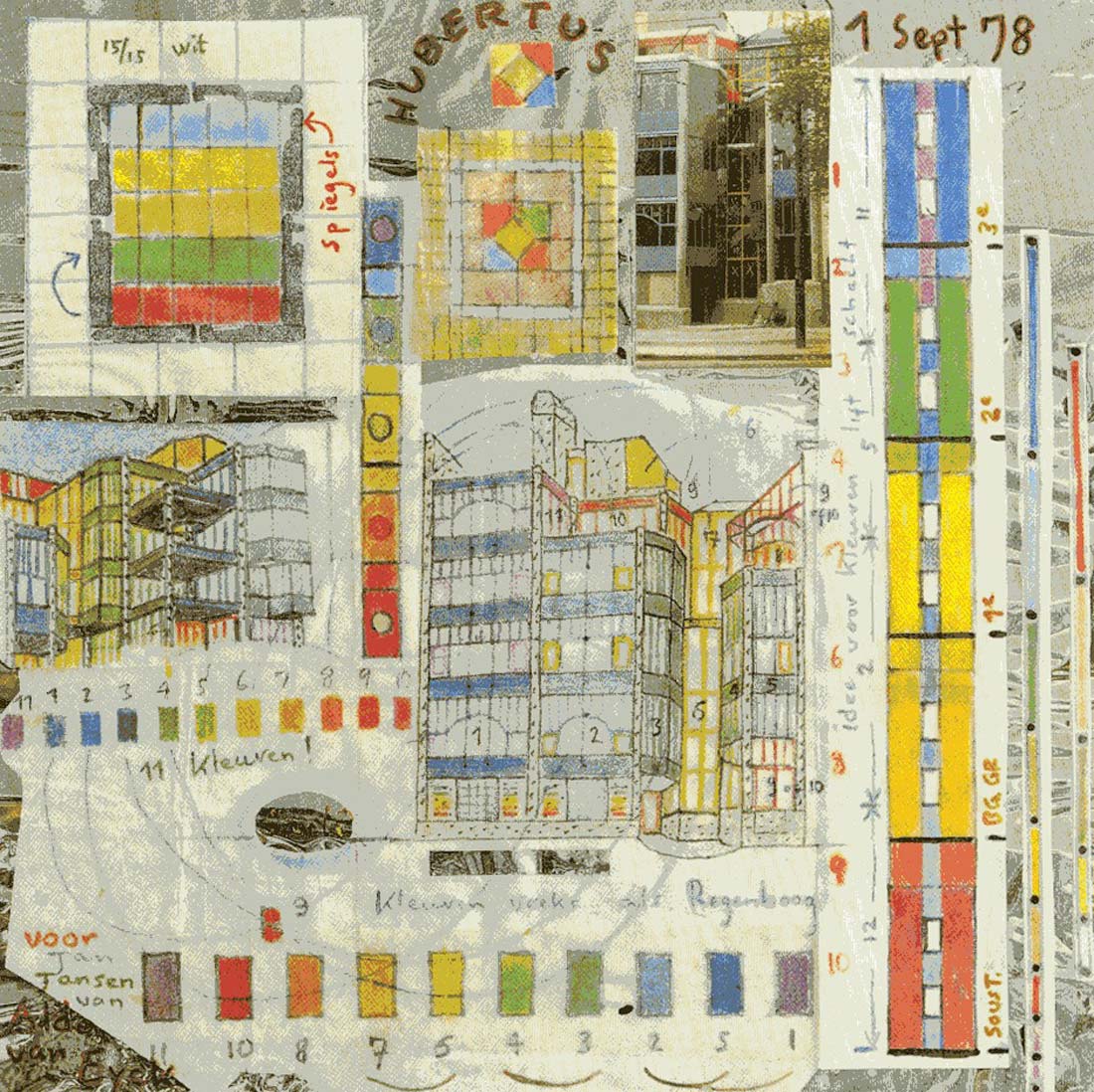

Aldo and Hannie van Eyck, Hubertus House, Home for Single Parents and their Children, Amsterdam, 1973-1981

The story of modernism starts with the appropriation of this space. When the open parade grounds and church squares were turned into avenues for circulation and empty spaces where the middle class could appear, a new kind of world opened up. It was a place organized according to the needs of the middle class and where they could show themselves or show off. Building on some of the earlier prototypes where the middle class had controlled space, as in the Netherlands, these new middle-class places began to take over more and more of the city. Appearing first on what was the edge of the city, they gradually became or took over the city’s center. Along the way, places were produced in which the middle class could literally be at home: storehouses for human beings called apartment buildings. These were efficient grids for living that still cloaked themselves with a thin veneer that made them look like the palaces of the rich, but which dissolved on the inside into modular spaces inhabited by different families at different times.

This public space was not the only one to appear as the place of the middle class. At the edges of daily life, new kinds of spaces made possible by technology rose up. Their basic elements were glass windows and their frames; their basic space was that of the grid. Their prototypes were not only the factory or workshop, with its rational and empty space, flooded with light that allowed for the most efficient production of goods, but also spaces for commerce and social mixing that opened up starting in the eighteenth century in the city itself. The gallery and arcade, the rows of shop windows with their glass facades set in a gridded frame, and the temporary framework of the stall or fair all set the stage for a new kind of space that finally came on its own. It developed after new technologies appeared that enabled the production of large plates of glass at an affordable price, as well as the thin frames made out of metal that could contain them. First used in exotic locales such as greenhouses, these spaces showed themselves off in exhibition halls and other temporary celebrations before becoming part of the city’s fabric. Designers used the methods of abstract thinking to plot rational and logical organizations of space, first for military and ritual uses, and then for production, consumption, and eventually living. New technologies made construction of these places of consumption and production affordable to the middle class and easy enough to adapt to meet their continually changing needs.

When these spaces revealed the gridded reality out of which they were made, they also revealed new materials. At first, designers treated metal and the grid of wood, or later steel or concrete, as something to be hidden, but soon these materials were flaunted and became the way to instantly tell that a building was new and belonged to the world controlled by the middle class. These spaces also were at their grandest when they contained the engines of the transformation of reality. The train stations and the exhibition halls at the edge of town, as well as the department stores that appeared in the heart of the city, replaced the churches as the largest structures around, and developed their own cults of objects and rites of adoration and consumption. Over time, these objects became smaller and were integrated into the life of the middle class. They became the implements of daily life, from sewing machines to toasters to, eventually, cars and televisions.

A third phenomenon appeared along the way: embedded technologies. A hidden space began to appear in the city, one inhabited by and connecting machines. Tunnels were dug for underground railroad systems and for the sewage lines that made the inhabitation of public space really possible. Gas lines and later electrical lines coursed through the city, transforming space from something you experience only during the day to a completely artificial place liberated from nature by human-made light. Eventually, even more invisible rays and emanations turned almost the entire world into a place of middle-class habitation, allowing you to be wired to information or trade goods even in a cabin in the deepest woods. These hidden systems, snaking out into the area beyond the city and eventually across the globe, spread middle-class space and made it ever more abstract.

Giving shape to space and technology was a challenge that designers confronted in the middle of the nineteenth century when they became clear and evident realities. At the same time, design turned from the hobby of aristocrats or a collective activity into a profession. Spurred on by the rationalization of all cultural activities initiated by Louis XIV and his ministers at the end of the seventeenth century, schools began producing trained designers, and the state began regulating their activities. The teachers at these schools used the same tools that had produced space and technology to discipline activities. Geometry, invention, rational thought, and the fact that you could make your living by trading in such abstractions all led to the formalization of architecture and design into viable trades. In architecture especially, however, there was always a nagging problem with this newfound definition of design. The schools used ancient models, and designers had to build what had been made in the past. They had to work in cities that were never quite modern, using existing building trades and materials, as well as artistic and legal conventions, that lagged far behind the ideas and technologies they knew to be available.

This uneasy position was not particular only to the design fields, though it was especially evident there. The middle class had few models on which to base their space and their appearance, other than those established by the aristocrats. The history of the nineteenth-century representation of space and technology is, like that of painting, sculpture, literature, and music, one of the acceptance, deformation, and finally undressing of these inherited modes. That has become the canonical tale of modernism: how the past was abstracted, rejected, or deformed to such an extent that something appeared that the new class of people, whether they were artists or the bourgeoisie, could call their own.

As a result, modernism took on the quality of representing not what was but what should be. It became a prospective movement, digging down through reality with the tools of abstraction and geometry to discover some form that it could posit as a rational truth which it could then reveal and extrapolate over all of reality. Modernism became a “movement”—itself a telling phrase, implying that this was a process that was never quite finished, as there was an ever-purer truth to be found somewhere in or beyond modernity. The search was one for pure space, pure technology, and the pure representation of those phenomena. A completely open space made possible by technology became the goal.

Modernism articulated these goals in contradictory and halting ways in the second half of the nineteenth and first half of the twentieth centuries, producing experiments along the way that produced startlingly new objects, images, and spaces within the city. This period was the most self-conscious moment of modernism: a time of fervent debates, manifestos, and a millenary belief in the ability to make a perfectly modern world. As it became evident that a new world was literally rising all around the makers of that world, designers threw off whatever they had inherited with exuberance and even violence, reveling in the destruction of place and the human form as well as in the construction of space, machines, and their representations.

After the First World War, at a time of tremendous scientific and social upheaval, this modernism applied itself to producing the results of its experiments at an ever-larger scale. As modernist space was meted out in apartment blocks and whole neighborhoods, a kind of consensus style, though with many variations, developed across the globe. Modernism in architecture and design relied on glass and steel, concrete, and soon plastic. These were human-made and fluid materials that allowed shapes unknown in nature and unrelated to the human body to appear. Designers now either used grids with pride or, paradoxically, covered their edges, producing forms that were streamlined to encourage the movements of modernity as well as expressing them. At the same time, these modernist designers claimed to look at both nature and the human body, abstracting them into geometry and pure white. They rationalized space into gridded environments and condensed machinery into compact elements. Representing the modern world as nothing but emptiness, modernist designers tended toward the love and production of pure nothingness.

At its most extreme, modernist architecture and design wished for its own disappearance. It wanted to be the nothing that underlay modernity—which is to say, the zero that allowed modern science and modern capitalism, the vanishing point of the perspective that allowed for the organization of space, or the point in the future toward which a society based on progress, the ever increasing profits and the ever more rational organization of reality, tended. It wanted humans and nature to fuse through the agent of technology into pure space.

Unfortunately, this nothingness turned into the destructive forces that killed millions of people during the Second World War, the forces that sought to wipe out nature Architects and designers found themselves complicit with this wholesale destruction of humanity, helping to create environments that were so vast and so abstract, so defined by technology and so radically new that they became the very emblems of the alien world humans were creating for themselves. At the moment of its greatest triumph, modernism turned from a millenary project meant to produce perfect space through technology, which would be a home for whatever humans might become in that new world, into a force that seemed to be destroying nature, the human body, and the past. It also threatened to do away with all that remained by which humans knew that they were not just elements in modernization, but something that they were rather that which remained, that which was always outside of those processes even if humans caused them. When modernism turned from a movement into a lived totality, it became an alien thing, and many began to seek alternatives to it.

Of course, not all designers were part of modernism’s movement toward a kind of productive nihilism. And many designers who did find themselves in this movement tried to turn that progressive drive toward nothing into something more conducive to human habitation, intelligence, and control. Some of the most beautiful moments in modernism occurred at the edges of the movement, where designers tried to engage forms, places, and images beyond the making of a middle-class emptiness and technological future. Some designers tried to join a social and political revolution that they believed would let the middle class, as well as the rules of nature, disappear. Others tried to integrate technology and nature or turn the shaping of space into the making of places with definable and recognizable boundaries. In doing so, these designers had to give up some aspects of modernism, eschewing geometry or reason, emptiness or technology, or the combination thereof. They became interested in that which remained even as modernization scoured everything that was not efficient and productive.

At the core of many of their activities was a way of working that was itself premodern and yet had become a central part of modernism: collage. Design became the gathering together of the fragments the modern world had created, assembled as if by chance, and organized in a way that was not rational and that carried the associations of all the objects contained in the finished product along with them. The result was an artifact that, like the modern world, appeared never to be finished. Collage and assemblage became the alternative to the perfect nothing of modernism.

It did not, however, appear possible to make many things in that manner in a society and economy still defined by the cycles of production and consumption. One of the great unfinished projects of the second half of the twentieth century became the transformation of the whole world not into nothing but into a collage of disparate, already existing pieces that were open enough to allow for continuous change, adaptation, adoption, and interpretation.

Eventually, however, many designers rejected modernism altogether, attempting to resurrect a world that had existed before the modern world became an inescapable fact. By the end of the twentieth century, many designers were looking backward, not forward, and most had come to realize that modernism would not and could not lead to a perfect and pure nothing, at least not in any way that a human being could experience. The rejection of modernism could never be total, though, both because it proved impossible to reject all technology and all rational ways of building, and because the middle class continued to be both the group commissioning most design and the class to which most designers belonged. The past was resurrected to become once again a cloak thrown over this reality, and thus a thoroughly modern thing: a choice of a way of appearing. It was not by coincidence that the debate between the ancients and the moderns was revived at this time.

A few designers speculated that the answer to the question of how to survive in a modern world and how to represent that act of remaining was to reject the very notion of the human being altogether. Many more put their faith in the latest technology, that of the computer, to produce something that would be truly modern. In the computer, space and technology would finally fuse to create something that would dissolve human action into the continuum of a completely smooth artificial landscape (in the act of design, for instance, which was to become the mere interpretation or guiding of the computer program, if that).

At the beginning of the twenty-first century, modernism has dissolved into a variety of different ways of making things. They range from a self-conscious continuation of the methods developed over a century ago to represent modernization to the collages and assemblages that reuse what modernity throws up into objects, spaces, or images and that are themselves only temporary. Though these directions appear disparate, they are connected. They share common roots and common working methods. Most importantly, there is no goal to these modes of modernism other than the one that started the search for the utopia of nothingness in the first place: how to represent, figure out, and make ourselves at home in a modern world.

OMA / Rem Koolhaas, Kunsthal, Rotterdam 1987-1992

These modes operate within a modern world that has become almost total. Today there is almost no place in the world that exists outside of modernity, which is to say, that is not made by humans, infused by technology, or accessible to our experience only through the modes of thinking and behaving that are modern. We live in a global space, one that is completely fluid and abstract. Place and time dissolve as we speed along in cars or airplanes or, even more, on the Internet. Capitalism appears completely triumphant over all remaining ideologies. Even those people who would seek to resist modernity have to do so on its own terms, claiming science for the creation of humans by a deity or attempting to destroy spaces of reason through violent technologies. Ironically, the most extreme forms of modernism and its most adamant rejection have come together, as they have over the last two centuries, in the postulation of nothingness, whether positive or negative. The other modes of modernism can only reject this rejection and try to produce a modernism we can use, understand, and inhabit.

This book attempts to trace the development of these very attempts, from the first appearance of the empty space that was the physical manifestation of the modern world, all the way to the dissolution of that space into the ether of the Internet. Certainly, modernity and modernism both began long before the first designs described in this book and will continue long after this book is published; and certainly, modernism occurs in modes that are far beyond the purview of architecture and design. In this book I will trace only the astonishing opening up of a brave new world of open empty space, the arrival of the beauty and terror of the machine into daily life, and the attempts to represent them in the construction of a modernist world. I believe modernism is a beautiful construction, one that I wish to both inhabit and show to you as reader.