An actionable tool

The challenge of UDTs is helping to provide high-quality built environments, more sustainable and resilient, for people. In general, these tools have to serve a purpose, be trustworthy, and function effectively (Bolton et al., 2018). Beyond issues with major integration challenges (Jeddoub et al., 2023), for having a meaningful digital double closely connected to the physical system (Gerber et al., 2019), the human factor is frequently missing. People need to be considered both from (i) the behavioral (i.e. what it means to consider human preferences, cognition, actions, and socio-cultural aspects) and (ii) the interaction point of view (i.e. what and how can be changed in the digital representation, how preferences and opinions are collected, what are the game rules).

UDTs can be effective tools to test out policies and planning decisions without risk at a minimal cost than in physical reality (Dembski et al., 2020; Mahajan et al., 2022). The development of digital representations of complex urban socio-technical systems enriched with immersive methods of participation, interaction, and feedback for people can provide more effective city planning than existing processes for decision-making (Abdeen & Sepasgozar, 2022). Following these needs, such systems should be able to generate urban planning answers informed directly by a continuous feedback loop created from the interaction of citizens with the urban digital double, the future visions, and also interactions among them. Overall, such frameworks should be able to automate at some degree decision-making, data and preferences collection, feedback gathering and aggregation, processing, visualization, and the generation of alternatives with hybrid intelligence (Dellermann et al., 2019; König et al., 2017), transparently and consistently (Lock et al., 2021). It is, with humans involved and participating in the process, potentially supporting consensus building and democratic processes (Dembski et al., 2020; Helbing et al., 2023).

The motivation for these planning tools is two-fold:

i. Cognitively, by raising situational awareness (Shahat et al., 2021) in the present and future, and bridging the knowledge gap for people when informing their opinion and decision-making regarding complex city-making processes, where participation is increasingly more important;

ii. Operationally, by introducing into UDT models a range of hard-to-measure and uncertain human, social, cultural, and psychological aspects in a machine-readable way.

Partially mirroring BIM collaborative environments (Cardoso Llach & Argota Sánchez-Vaquerizo, 2019), without the hierarchical and finalist constraints, UDTs can help to humanly fine-tune the space of suboptimal solutions according to citizens’ (and other stakeholders’) preference. A common framework, ideally with publicly defined standards, where different stakeholders can build their own instances in a federated way. Common, interoperable, but at the same time able to host and integrate individual interests, variations, and models. Thereby, this framework of hybrid knowledge could overcome single-dimensional utilitarian optimizations to provide a set of solutions that can satisfy reasonably a diversity of requirements, agendas, and needs. It means pluralistic solutions, and diverse scenarios from collective intelligence supported by aligned machine intelligence (Zaremba et al., 2023) that benefit many different people.

Code is normative and performative

Building codes and other legal texts regulate spatial occupation, land use, and activities that may happen in space. They have a deep impact on the shape, material, densities, and actions that give place to the built (urban, suburban, and rural) environment (Easterling, 2014).

Institutionalized building codes, as a law, have a deep impact on people’s lives and perform of urban spaces (Prytherch, 2012). It determines what and what is not allowed in different parts of the city, which activities and land uses are compatible, and up to which point. It defines densities, built-up surfaces, separation between buildings, occupation of plots, maximum heights, materials, views, infrastructure allocation, public services, distribution of housing units, minimal habitational conditions, shadows, views rights, energetic performance, etc. As such, typological, formal, and functional changes in cities can be analyzed as the final expression of changing building codes and standards over time (Bubola, 2021). In this sense, building codes are spatially and socially performative and normative. It sets and primes human behavior. Overall, it determines the many affordances of spaces. Hence, it can enhance or cancel social and behavioral traits and productive economic activities.

Code as software is equally performative and normative. It regulates what can and cannot be done in physical and digital spaces (Dodge & Kitchin, 2005), and how consistency and trust can be built in such systems. Following the idea of the Internet as a predictor of what is yet to come in more immersive, interactive, and embodied virtual worlds coupled with physical reality, the Web is a socially produced space as it is the urban space (Lefebvre, 1974). However, it comes with the additional constraint that its affordances (Gibson, 1979) are fully limited by the underlying code (Proctor, 2021) even in a more restrictive way:

- Computational legalism: While conceptually similar, software code is more rigid, deterministic, and not subject to interpretation as legal code (Diver, 2021).

- Software-based environment: This type of code is radically defining because it defines all that can be done and built in digital spaces as the own existence of such a digital environment relies completely on code.

This sets a completely different implication of the nature of code as a behavior determiner that is not so acute in physical space. Furthermore, code, even more radically in virtual-based digital spaces, is much harder to hack and circumnavigate, as it accounts not only for what would be conventional norms, rules, and assets in the physical world. It defines also what would be equivalent to the simplest physics and natural laws. In sum, algorithmic governance takes a new and almost totalizing meaning: following the logic of smart contracts, they are executed automatically and deterministically, all the time, permeating every single aspect of these environments, from interactions, pseudo-physical laws, presence, aesthetics, actions. This requires all these elements in tangible, countable, and tokenizable, either for control and ownership purposes, or just to reconstruct digitally some, already lost, sense of aura, value, and authenticity (Kalpokas, 2023; Walter, 1936), if not to retrofit digital abundance with digital commodification (Horkheimer & Adorno, 1947) and a form of simulated scarcity (Bocquillon & Loon, 2022). This power is even more relevant given the known persuasive power of computational frameworks such as the polarizing effects of social media, or by influencing human behavior and opinions such as the case of dark patterns (Fagan, 2024; Reviglio & Agosti, 2020).

Considering (i) the physical, situated anchoring of these UDTs, (ii) their envisioned relevance for governance in these locations, and (iii) the participation of individual and collective (i.e. companies, governmental bodies) stakeholders to exchange their opinions, interests, and concerns, the agency, ownership and sovereignty of these systems cannot be ignored. The convenient outsourcing of the physical infrastructure that supports these cyber-social systems cannot be separated from the governance and policymaking process that they are supposed to support. Also, while digitizing aspects of daily life may save energy, human, and material resources, it comes with the tradeoff of ramping up the resources needed to keep up this physical IT infrastructure. The current development of socio-technical systems for participatory governance and co-creation in cities generates a paradoxical, and potentially risky, situation. To be really actionable and operationalizable these systems need to increase their level of complexity, which simultaneously require relying on larger resources and humongous computing infrastructures that do not belong to the instances that they are supposed to support. They escape public accountability and control. On the contrary, they depend on very few extremely powerful technological players, privately-owned, and market-driven. This compromises sovereignty, self-determination, and the definition of public good (Gstrein, 2023), together with technical risks to centralization and concentration of service providers. What kind of digital illusion is a decentralized and federated metaverse whose needed physical infrastructure depends on a few players?

This ubiquitous and pervasive presence of code and data expands the inherent risks already identified for data-driven smart cities such as dataveillance, geo-veillance, anonymization and re-identification, obfuscation and reduced control, and empty or absent notice (Kitchin, 2016). Also, it includes other risks that are generally associated with data-driven systems such as data and algorithmic biases related to quality, transparency, accountability, representability, agency, and fairness. While decentralized approaches promise to create a self-organized and self-regulated governance scheme, fundamental concerns remain as they may be necessary but not sufficient conditions for ensuring this (Edelman, 2021; Goldberg & Schär, 2023), nor may be participation alone sufficient. Regulatory strategies may be needed (Rosenberg, 2022; Suffia, 2023) and they could help to establish standards and common practices that may help to solve issues related to interoperability and scalability.

Limits and risks of Urban Digital Twins

UDTs can be powerful tools for planning and simulation. They provide solid support for civic engagement that contributes to more effective decision-making processes. However, their implementation, particularly the deeper that immersive virtual environments are implemented, leads to societal, legal, and ethical risks that can enhance social divisiveness among other issues.

At a very basic level, validation is one of the main concerns. Starting from the acknowledgment of the limitation of the data itself, and their known biases, how can we make sure that the model matches the real dynamics and functioning of the city? This validation process becomes even more complex when considering the most uncertain components, such as human behavior and cognition. Ensuring that these models capture the diversity and unpredictability of social systems is a significant challenge (Caldarelli et al., 2023). However, these systems usually rely on automatic data-driven algorithms and processes without human intervention. The idea that more data will provide more efficient and better decisions necessarily builds on top of massive data collection. Immediately, this raises the question of ownership, agency, and access to data, which ultimately is another enhancer of social divisiveness (Andrejevic, 2014). This expands the whole need for consideration of the human factor beyond purely technical and functional requirements. The benefits of UDTs are not automatic and require a multi-disciplinary approach that takes into account a socio-technical perspective (Kitchin, 2015; Nochta et al., 2021).

The need for data, and its own commodification, force the virtualization of every single asset or aspect into the digital realm, including human behavior, thoughts, and emotions (Bibri & Allam, 2022). Precisely, what is hard, uncertain, or intangible in the physical world needs to be tangible, quantifiable, and computable in the digital world, making every single action easier to monitor in virtual environments, and strengthening trends of surveillance capitalism (Zuboff, 2023). Or what can be more concerning: constraining and nudging human behavior and agency to match the parameters of what can be modeled and measured. An immersive virtual environment may be the perfect realization of a data-controlled and measurable environment: a self-fulfilling prophecy where now everything is, and needs to be for being, measurable, tractable, tokenizable, and monetizable. Virtual environments may provide societal and cognitive advantages (Graham et al., 2022; Hutson, 2022), although they deepen on existing concerns regarding privacy, transparency, accountability, freedom, and fairness in connection with massive surveillance and data –and algorithmic—bias (Helbing & Argota Sánchez-Vaquerizo, 2023). Furthermore, the metaverse in its different implementations can expand the already existing unrealities that people decide to live daily (Eco, 1986). As a consequence, it constitutes a transhumanist escape (Barachini & Stary, 2022) to disregard and ignore the constraints and problems of our physical world (Bojic, 2022; Han et al., 2022; Pal & Arpnikanondt, 2024).

Also, an intense dependence on software makes it vulnerable to the own constraints of how we have created our computer-based technology (Leveson, 2012), including security and obsolescence issues (Strickland & Harris, 2022). VR studies have been proven to be useful for applications in many fields and tasks (Dubey et al., 2018; Sanchez-Sepulveda et al., 2019; Whyte & Nikolić, 2018). However, while advances regarding vision, haptics, and other senses are an active field of research, the whole cognitive process of embodiment and presence may require more sophisticated, and potentially more neurologically invasive approaches (Pisarchik et al., 2019), to be able to match the experience of physical presence. Natural and social conventions that exist in the physical world, and the tangibility of people and goods exchange and ownership need to be redefined by code from scratch in virtual environments (Huynh-The et al., 2023; Zwitter et al., 2020). If blockchain would make trust unnecessary for human relations and interactions (Edelman, 2021), it is the metaverse where it can really flourish, due to the lack of real embodiment. Hacking the physical world is harder and more obvious; humans are more adapted to detect it. Since it is code-based, it presents easier opportunities for inconspicuous hacking, affecting the people who inhabit it as avatars. For instance, it is relatively easy to notice somebody hiding in our vicinity or some device trying to spy on us, but what happens when the endless data streams needed for defining every single interaction in the digital world can be incepted or other identities can be completely camouflaged into the environment? What kind of countermeasures should be implemented? (Lee et al., 2021; Wang et al., 2023).

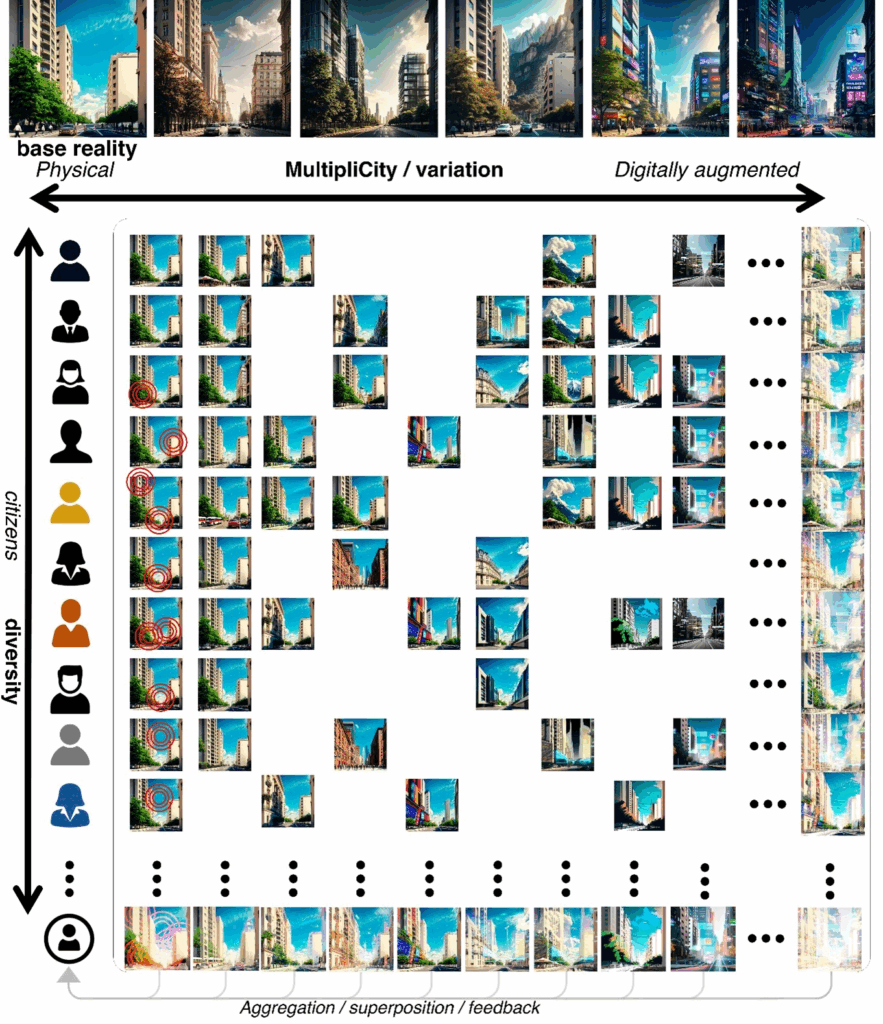

Digital doubles, including metaverses, are ultra-plastic and endlessly replicable: everything can be changed, cloned, and transformed, at a minimal cost. This provides advantages for adaptability, diversity, and testing in comparison with the tectonic, physical, heavy, and tangible physical environment. However, this flexibility makes metaverses require clear rules and procedures for interaction that need to be designed to be useful and remain coherent and consistent (Hudson-Smith & Batty, 2023). Each representation of a city within a UDT, with its myriad of alternative scenarios and changes and modifications due to personal preferences, is different, which challenges cohesion and integration. They may be mirroring only partial aspects of the physical environment (Helbing, 2013). They may respond to non-existing alternative scenarios to be explored and analyzed. They may be customized variations chosen by individuals to match their needs. If this multiplicity would not be enough, on a more fundamental level, each of us does not experience the same environment in the same way. Each person and social group focus, prioritizes, and is affected differently by different components, layouts and features of the city. Even if the experience of each social group or individual is always partial in the city, the whole set of urban dwellers identifies the whole as a single entity. This effortless replicability can boost the creation of individual versions of an XR leading to an intense digitization of urban life makes easier to extend spatial segregation and accessibility restrictions to citizens (Cardullo et al., 2019). Making significant parts of urban life only accessible through technology may widen existing digital exclusion issues. This would hinder the attempt to create a common united identity within a city expanded in the digital world. We will face integration, interoperability, and scalability issues (Cheng et al., 2022) to ensure togetherness.

Fostering citizen participation is not an automatic fix for the shortcomings of computational methods, nor for unblackboxing some of these technologies (Sloane et al., 2022). Participation by itself won’t solve immediately political challenges related to the prioritization of goals or defining what is the common good (Zografos et al., 2020), nor the use of digital twins will take over the construction of democratic consensus despite its power to smooth communication between stakeholders (Yamu et al., 2023). Thereby, new and richer methods for assessing the quality of this digital participation need to be explored and developed (Ataman et al., 2022). Citizen participation is a key element for sustainable urban development (Bouzguenda et al., 2019) and UDTs facilitate the decision-making process by easing the simulation of future scenarios and policies (Mahajan et al., 2022), by making their results more understandable, and by smoothing and enriching exchange between stakeholders (Haraguchi et al., 2024). Even further, these complex cyber-physical systems can perpetuate knowledge, agency, and power inequalities. Thereby, it is needed a socio-technical and participatory perspective in the development of these tools, beyond pure technical feasibility, enhancing aspects of trustworthiness and purpose, which often require very local and situated knowledge, encompassing also organizational culture to reach actionable levels of trustworthiness and legitimacy (Bolton et al., 2018; Nochta et al., 2021). This can ease the challenge of integration and acceptance of shifts in policymaking. Many of the existing initiatives focusing on marketing, business, and finance may be rendered deceptive due to a poor functional experience and lack of valuable purpose within these domains beyond the initial hype. However, this highlights the opportunity and promising value of urban metaverses based on UDTs conceived as co-creation, exchange, and sharing environments oriented to governance, policy, and planning.

By now, in the end, the digitalization of the urban realm as we have known until now has ended up being very different. Instead of developing bottom-up participatory approaches to empower people via open-source technology, it was taken over by corporate, capitalist, and market-driven approaches (Greenfield and Kim 2013). This perpetuates power inequalities (Egliston & Carter, 2021) and control with social consent (Han, 2017). Finally, UDTs, understood as a technocratic continuation of smart cities, are not quite there yet regarding community participation (Axelsson & Granath, 2018), but neither regarding standardization, interoperability, and scalability (Cheng et al., 2022; Shahat et al., 2021). From a societal and cultural point of view, the outmost question remains about how important, needed or even required would be these technologies to live in cities. Beyond being a nice and convenient add-on to daily life, or being a potential enhancement of social and experiential segregation, it is yet to be proven if their functionality, purpose, and trustworthiness can make them fundamental components of daily life, marginalizing people who are not participating of them (Cardullo et al., 2019).