Renovating the Global InteriorThough U.S. news media show climate change and oil depletion as partisan matters of opinion, major institutions—from insurers to armed services—have sidestepped these conflicts to form plans of action. Architecture firms have codified sustainability principles into a straightforward set of best practices: embrace LEED standards and renewable products, or stay out of the way while engineers and bureaucrats handle it.

Technical tweaks—insulation, tree planting, upzoning, heat recovery, transit overhauls, and smart grids—can help maximize services while lowering bills. But they don’t merely save energy. They also support narratives on lifestyle, property rights, and the horizons of political possibility. As we survey these approaches, we must also map their blind spots in order to move forward. Infrastructural solutions demand largescale action, but who has the means and authority to execute them? If the American Dream has taken shape in times of crisis or rapid expansion, can it emerge in an era of slow growth and limited government?

By delineating economics and ecology, architects and planners trouble familiar figures of the city, even as those figures themselves change. Designers manage resources, systems, and organisms by reimagining the good life at all scales. In this way, they can replace a scarcity-driven model of sustainability with one that acknowledges the struggles inherent in governance. While sustainability defers to the invisible hand of the market and keeps its hands off Mother Nature, a more ambitious approach seeks new energy problems as well as solutions.

Domes

To fuel ambitious strategies, architecture must rethink performance. Modernists optimized a short list of variables: labor, material, and square footage. In an era aware of climate change, we need to manage multiple definitions of efficiency to address an expanded constituency. A broader set of metrics could measure not only carbon and dollars but also variables like housing availability, species counts, and resource equity.

Buckminster Fuller and Shoji Sadao’s 1960 proposal for the two-milewide (3.2 km) Dome Over Manhattan imagined a massive architectural surface that would regulate the city’s ecosystems. They delivered this design along with a series of surprising calculations: the Dome would reduce heat loss by scaling the city to 1/85 of its surface area; the elimination of snowplowing alone would pay for heat; buildings inside the Dome could be built lighter and cheaper without need for weatherproofing; and interior air could be heated by remote plants.

This grand scheme, while easily dismissed as technocratic megalomania, significantly proposed repurposing efficiency to address new criteria. By creating an overarching surface, the Dome would dislodge architecture from its conventional identification as a boundary between public and private. In doing so, it would make visible a redistribution of real costs and benefits to a different public than that implied by the Manhattan street grid. The Dome redefined efficiency by constructing a communicative surface of enclosure and energy distribution.

In a way, all buildings are domes—atmospheric enclosures that define collectives. Domes regulate climatic energy (Biodome), as well as agonistic spectacle (Thunderdome); they house utopia as well as struggle. Buildings mediate climate, vision, and bodies in ways shaped by politics. Architecture’s effectiveness as a technology of power flows from its naturalization of economic, juridical, and technological principles.

Guide

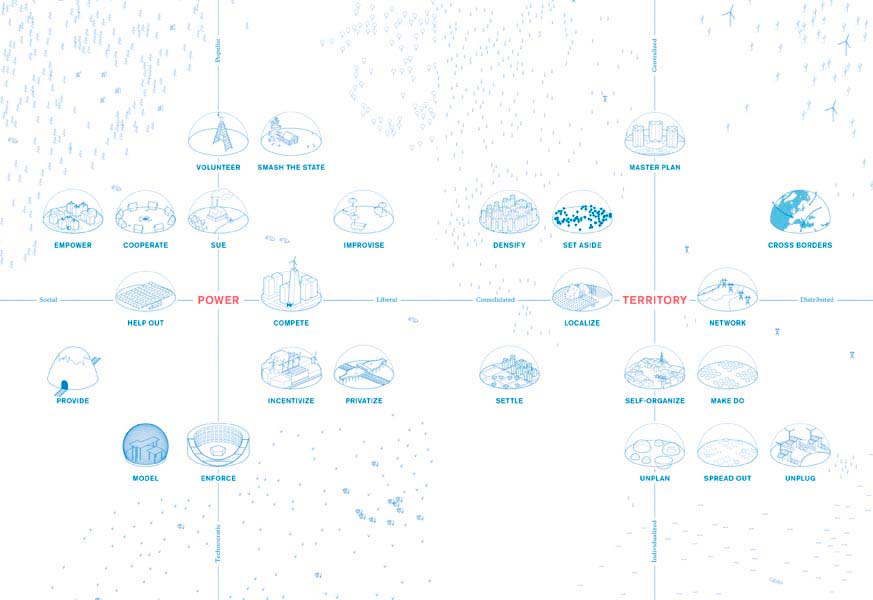

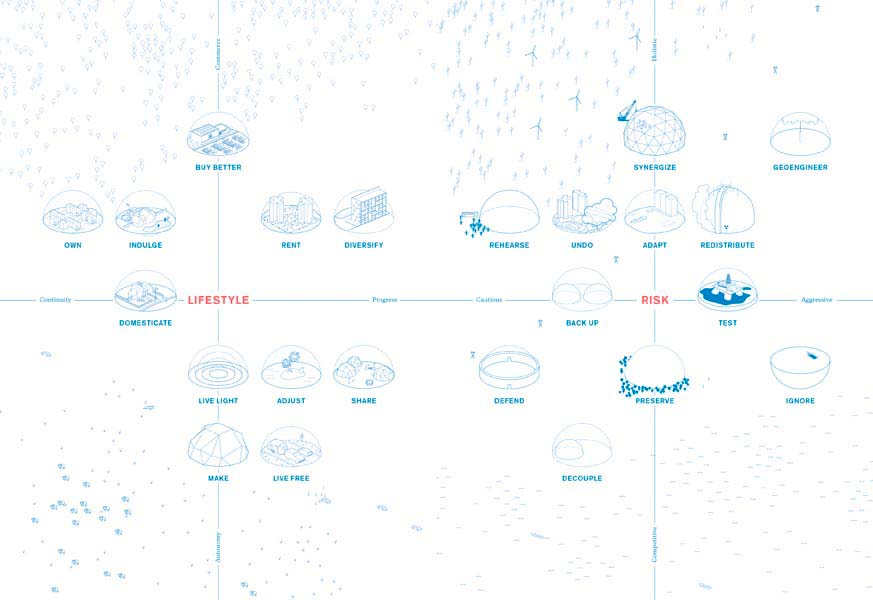

The Underdome Guide to Energy Reform depicts energy reform as a landscape of competing agendas. It maps icons of energy management schemes arranged around four fields of analysis: power, territory, lifestyle, and risk. Each agenda is located in the United States or American spheres of influence.

The Underdome Guide offers no guidance. Instead, it frames debates to inform the decisions that affect our environment. Like Architectural Graphic Standards, it illustrates a variety of techniques, forms, and managerial protocols in contemporary design. Like a voter guide, it catalogs ideologies behind energy rhetoric to enable participants in the building process to make informed choices and identify allied approaches.

We invited architectural thinkers to moderate discussions among energy experts from a broad range of disciplines. Participants in these conversations included architectural historians Reinhold Martin, Jonathan Massey, Michael Osman, and Meredith TenHoor; designers Denise Hoffman Brandt, Laura Kurgan, Georgeen Theodore, and June Williamson; engineer Andy Thompson; economists Moshe Adler and J. Scott Holladay; entrepreneurs Cary Krosinsky and Sarah Beatty; New York City and State government officials Laurie Kerr and James Gallagher; historian Jonathan Levy; journalist Heather Rogers; planner Rae Zimmerman; and policy advocate Petra Todorovich Messick. We include in the book transcripts of the events alongside essays by each moderator that examine one of four Underdome fields.

As sites for architecture’s agency in energy reform, “Power” considers questions of control, governmental and otherwise; “Territory” maps planning, land use, and property regimes; “Lifestyle” looks at sociability and the individual; and finally, “Risk” asks how collectives are formed to manage uncertainty.

Following are selected energy agendas from the Underdome visual guide.

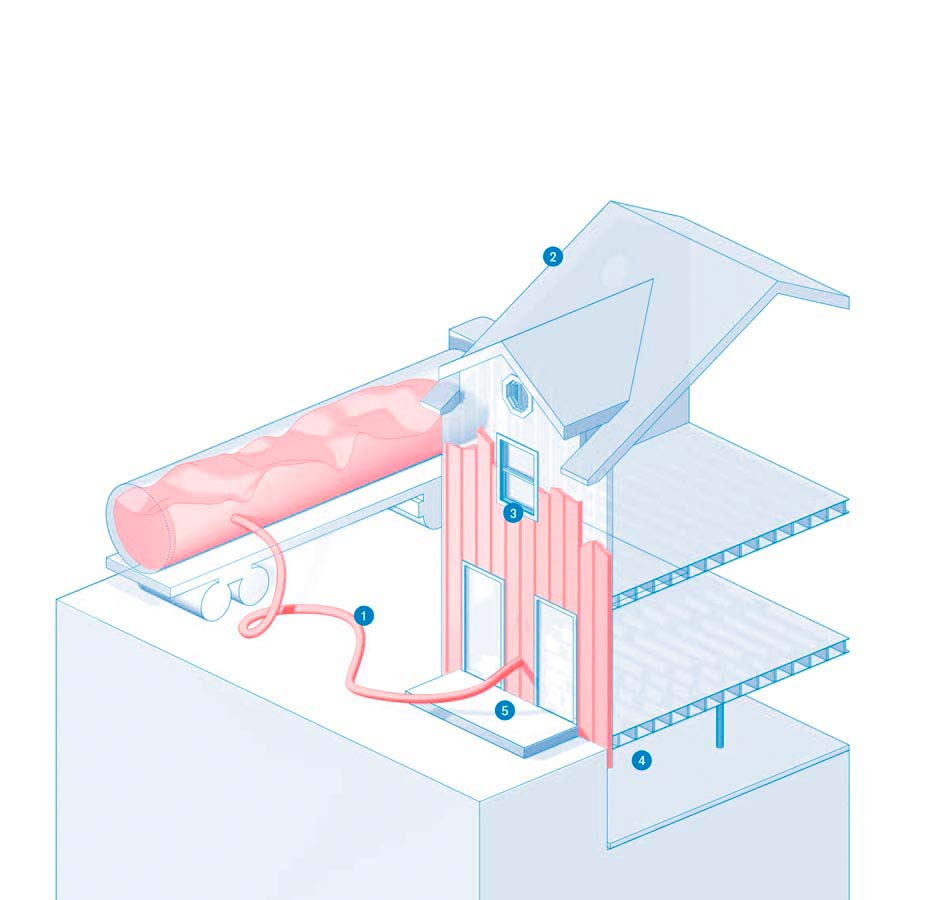

Provide: Government Construction

The government should invest directly in capital projects that bring both immediate upgrades in efficiency and net savings over time. The Federal Weatherization Assistance Program uses public funds to renovate the dwellings of low-income households, without regard for ownership status or building type. The program was founded in 1975 and is managed by the U.S. Department of Energy. It creates new spray foam “bubbles”, targeting energy efficiency measures ranging from equipment upgrades to retrofits of building envelopes.

1. Spray foam insulation

2. Cool-Roof reflective coating

3. Weather stripping and caulking

4. Replacement refrigerator, washing machine, chiller, boiler, and other equipment

5. Replacement thresholds

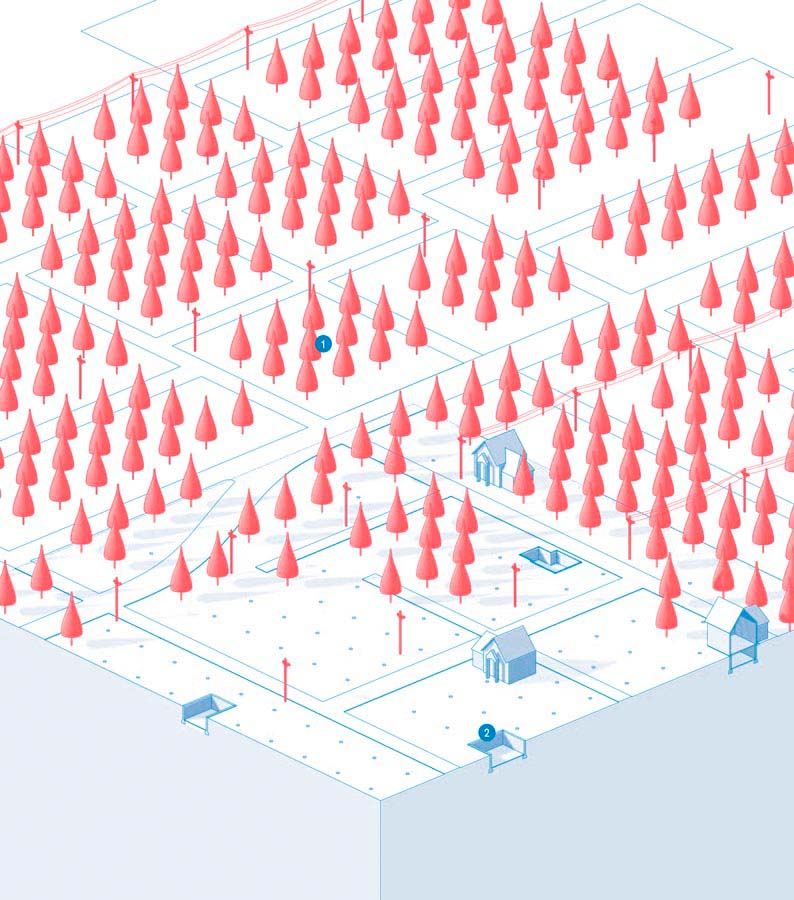

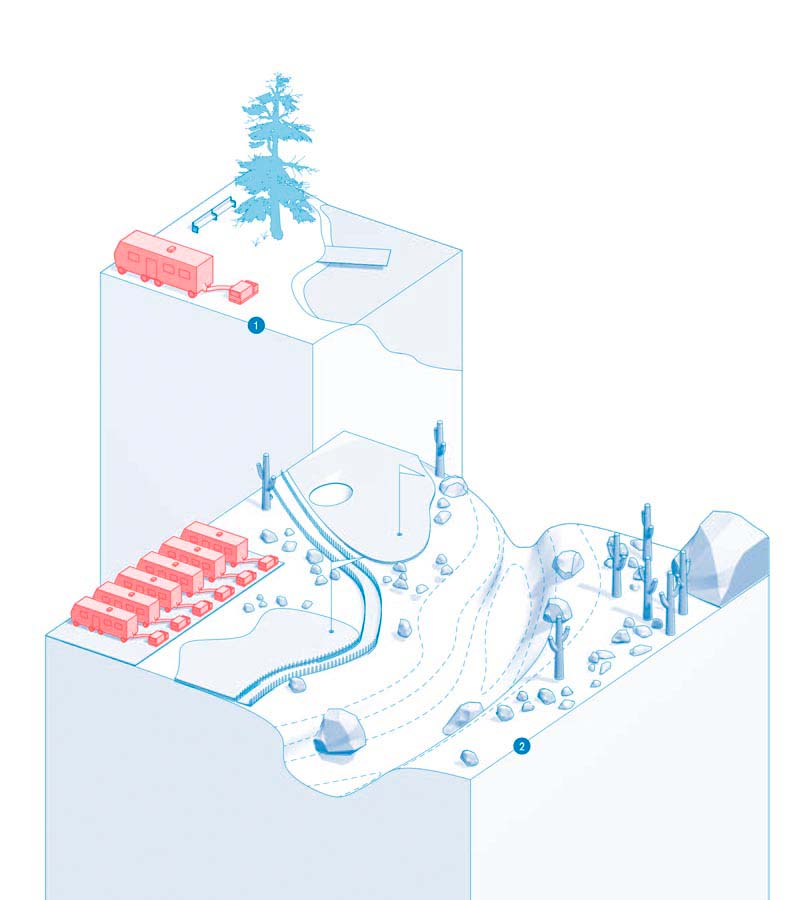

Spread out: Shrinking Cities

We must harvest vacancy. The aggregation of vacant properties can allow for territorial speculation, banking land today for improvement and sale tomorrow. Hantz Woodlands is a proposed forest and farm in central Detroit. In 2012 the local entrepreneur John Hantz purchased almost two thousand parcels of land from the city for an average of $300 per lot. The plan calls for the cleanup of vacant properties, planting of hardwood trees, and -as allowed by an urban agriculture ordinance passed by City Council in 2013- large-scale farming.

1. Hardwood trees planting

2. Demolished house

Live free: Self-Determination

We should enable mobile and nonconformist living, so that people can make their own energy choices outside conventions. The Salt River Project (Arizona) electric utility has pioneered a fast-growing payment program designed for transient and low-income customers to pay in advance and encourage them to conserve energy to avoid power shutoffs. The program was originally established for customers without a credit history but also assists Arizona’s snowbirds as they winter in desert.

1. Summer

2. Winter