“Talking about architecture bores me; I prefer making it instead.”

The quotation alone sums up who Fabrizio Carola was. As it suggests, any further description of his architecture would simply be redundant.

After all, it would be simplistic today, almost a month after his death, to see Fabrizio’s story as that of a “simple” architect. At the same time, I believe it is worth thinking about some of the different aspects of a man who was such an atypical figure in Italy and internationally. I hope Fabrizio won’t hold it against me.

I had heard about his work since I was a child through my father, an expert in tropical medicine with many experiences in Africa. Although I am Neapolitan like Carola, only as a student of the Architectural Association in London did I really get to know his architecture. And it was several years after the first letter I sent him that we finally managed to meet in Brussels, and then in the studio in Paris. Immediately afterwards, he invited me to join him in Mali to start developing collaborations between two apparently distant, but actually very close, worlds: my digital and its analogue. That was probably Fabrizio’s last time on the African continent; the conflicts in the region unfortunately did not allow us to develop beyond our collaborative project. But what he transmitted to me in those weeks we spent together will always fill me with pride and a sense of responsibility. So many years later, the African Fabbers School project that I am developing in Cameroon draws on the same human and cultural principles.

Carola’s was the story of an independent thinker, one of the few who have been able to develop theory via practical work, anticipating contemporary themes that are crucial for new generations – and for more than just architects. I’ll try to put in order a series of notes taken during conversations I had with him – now several years ago – in Sévaré, Brussels and Bamako.

A Citizen of a New Europe

At the age of 19, he decided to leave his native Naples to go and study in Brussels, despite having a guaranteed future in Italy as the son of a major developer. In 1950s Belgium, he would find in La Cambre – the architecture school founded by Henry van de Velde – a cosmopolitan environment, but above all an approach to design centered on the relationship between form and structure. An inclination to design in order to build was evidently in his make-up. But the school in Brussels, with its close connections to Art Nouveau, may well have prompted his interest in the links between architecture and the natural world. One thing is certain: his decision to “study outside”, his feeling that his identity was primarily European, and his desire to pursue a career independently of his origins anticipated what many of us have tried to do since.

From the time of his professional training, Fabrizio developed his own, highly innovative understanding of the architect’s vocation and social role. Without exaggeration, his projects – first in Morocco and then in sub-Saharan Africa – increasingly became the central elements in a tightly focused research agenda, which was equally experimental and rigorous.

A Pioneer of Post-Vernacular Architecture in Africa

Fabrizio very quickly understood that Africa was the right place to test an ecological approach to architecture, in which social, mental and environmental ecologies could flow into one another. He grasped that technology would have a fundamental role in this by making building processes sustainable. Above all, he understood – once again, before everyone else – how important it is to work in a state of osmosis with the landscape and the people living there. From this point of view, his interdisciplinary approach can be seen today as very advanced, despite the “primitive” techniques used.

In his work, the building site was also his studio – an applied research laboratory focused on an idea that was critical in Africa: self-sufficiency. Using this simple concept, he developed a method that could generate concrete responses to problems created by climate change, such as deforestation and impoverishment. Via a simple yet integrated process, he was able to transform the critical environmental and economic issues of a context into generative elements in his designs. Equally, his tendency to see the construction site as a place of production and dissemination contributed to giving his work its subversive character.

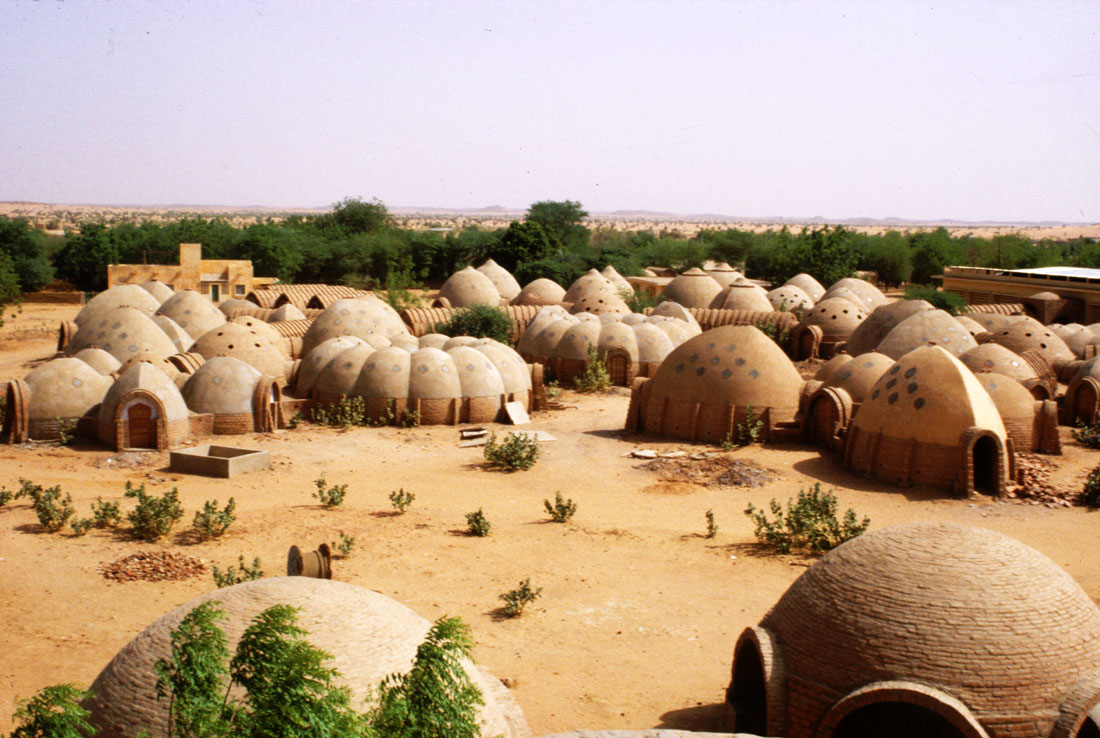

His idea of evolving Hassan Fathy’s compass to create building shells (such as domes and vaults) created entirely using “0 km” materials was just one product of this. Fabrizio, with his profound understanding of African society, understood how important it was to transform the construction world into an opportunity to redistribute wealth more equally throughout a community (such as a village or a town district). By reclaiming the vernacular sub-Saharan culture, he saw the potential for interpreting construction as a collective practice able to hold a community together, as happens in Djenne, in his beloved Mali, at the end of the rainy season.

The building site as a factory (for bricks, above all) became a strategic element in the definition of a sustainable approach, keeping the dependency on imported materials to a minimum and asserting a model of the circular economy long before we had a name for the idea. This holistic approach generated extraordinary buildings promoting the collective good, such as the hospital in Kaedi (Mauritania), the medicinal herb market in Bamako (Mali) and the research center for traditional medicine in Mopti (Mali).

An Innovative Educator

However, I believe that it is worth underlining another aspect central to his work: sharing. Although he kept his distance from academia, Fabrizio was always an educator. Above all, he understood how important it is for rising generations to “learn by doing”. To pass on his wide-ranging knowledge, he invented a system of “building site schools” that trained many young men and women over the years, European and African, even before architects. To have done all this, needless to say, you need to be more than an architect of genius – you need human qualities that are out of the ordinary. Among the many that I like to recall are his cultural openness, his consistency and his contagious enthusiasm – the same enthusiasm which prompted him, at the age of nearly 80, to jump on my Vespa to go around Paris and explain to me the ups and downs he’d experienced when creating the set design for Werner Herzog’s film Cobra Verde.

For the rest, there are theoreticians and academics able to praise his buildings probably better than I can and describe the role of his compass and the performance of the domes within domes. For me, and for all those who had the pleasure of getting to know him in the field, there remains the promise of continuing his teaching and the invitation to love Africa by going out and physically touching his work.