To interrogate the relation between governmental practices and the slew of recent technologies developed and deployed in the name of sustainability—whether ‘green’, ‘resilient’, ‘ecological’ or otherwise—is of course to interrogate the political status of such technology itself. How does the use of this technology expand governmental knowledge more broadly into a city’s population and more deeply into the intimate spaces and practices of the individuals and groups which compose it? How does it open new sites of intervention, new surfaces of interface between administration and the citizens which it oversees? What inherent directionalities do such channels of power presuppose?

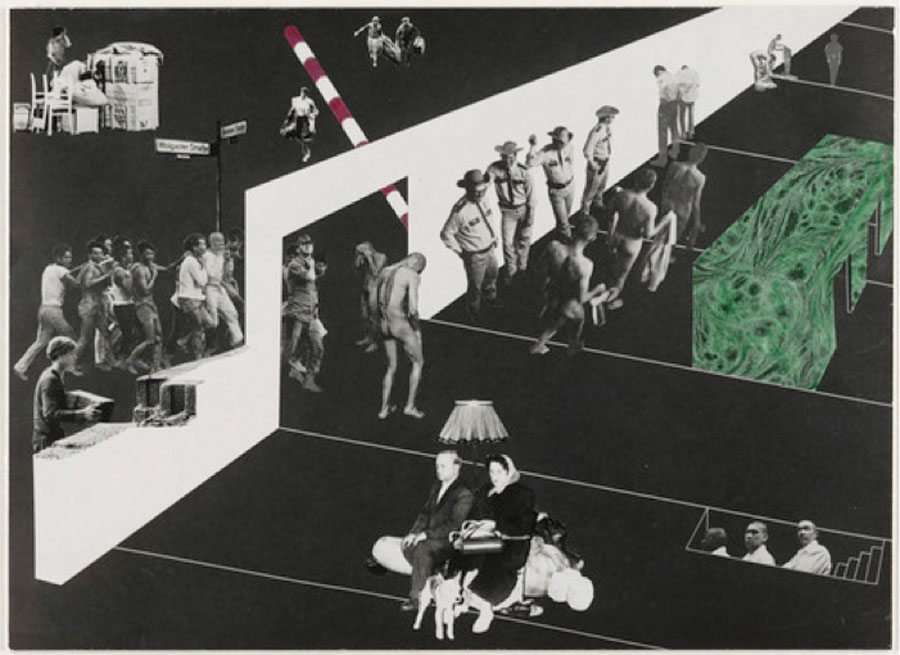

‘City Plus’, OMA, concept image for Rebuild by Design initiative. In their own words, ‘[t]his means further densification and defense of high value, high impact, high potential sites—cities’, 2013.

More to the point, what new forms of subjectivation (and desubjectivation) are produced by this blossoming array of spatio-governmental apparatuses and what possible consequences could they have for the future of urban life? Certainly proposals like that of Office for Metropolitan Architecture’s (OMA) recent contribution to New York City’s initiative, “Rebuild by Design” (a part of the Rockefeller Foundation’s 100 Resilient Cities project), highlight the urgency to ask these questions. The project depicts New York City as a fortified prison island, whose interior can be converted into a coordinated disaster relief zone if and when environmental disaster strikes. More than anything particularly novel, this project reveals just how readily we have already come to accept urban life as synonymous with a life in a permanent state of emergency. In fact, this is where the project is most explicit, demonstrating how, rather than relying on new technologies, the complete assemblage of existing technologies constituting the ‘normal’ urban condition can simply be augmented to instantaneously switch the entire city over to catastrophe management mode. Road signs, billboards, traffic lights, signage and even street vendors can all constitute elements within a synchronised administrative system drawing the boundary between emergency and non-emergency into non-distinction. Remarkably, the resemblance between this project and OMA founder, Rem Koolhaas’s, very first project some 40 odd years ago, Exodus, or the Voluntary Prisoners of Architecture, [1] stands as an ironic twist of fate bringing a radically critical project full circle and giving new clarity to Agamben’s provocation that the camp is indeed the ‘nomos’ of the modern. [2] This is not a problem isolated to a bizarre spatial experiment conducted on New York City; indeed, ‘resilience’ has rapidly moved to centre stage within spatial design and planning knowledge production. Harvard’s Graduate School of Design, for example, has developed a new programme of research on ‘Risk and Resilience’, [3] enlarging the scope of urban design to now include environmental calculations at a territorial scale. The prospect of a world conditioned by the permanent presence of environmental catastrophe has begun to transform notions of risk and resilience into multi-scalar programmes whose forms of analysis and sites of intervention promise to range from the individual (‘resilience starts with you’ [4]) to the terrestrial. And why not? In the wake of disasters like ‘Superstorm Sandy’, who would dare to question such ambitions? Its no wonder that development projects mobilising a rhetoric of resilience, by appealing to existential threats that have become only too familiar, garner almost universal support. Clearly in the face of these schemes, a sustained, critical discourse is urgently needed to counter the consensus these projects have already generated.

‘Alternative information delivery’, OMA, concept image for Rebuild by Design initiative, 2013.

However, while this line of inquiry is undoubtedly important, it seems equally as urgent to ground such questions within a broader scope; that is to say with regard to the nature of the urban itself. Indeed, as it happens in many discourses, from Architecture to Geography, Sociology to Anthropology, wherever the urban is raised as the site of inquiry, the problem always tends to be something else that it contains. Assumed to be a transhistorical background of human life, the urban appears never to constitute a problem in and of itself. To focus one’s critique on the various emergent ‘green’ technologies, just as much as to centre one’s research around radical social inequalities that form within cities, changing patterns of urban mobility, new forms of political struggle or emerging migration patterns within the urban world, and so on, risks leaving the question of the urban itself unexamined. In other words, it risks framing the problem around the technologies themselves, and not the milieu in which they are (and have historically been) deployed.

‘Reception Area’, Rem Koolhaas, Elia Zenghelis, Madelon Vriessendorp, Exodus, or the Voluntary Prisoners of Architecture, 1972.

Broadly put, my work is an effort to shift the focus from foreground to background, from the particularities of a given problem to the problem of the general frame in which such particularities arise. It is an attempt to engage with the notion of the urban from a theoretical and concept-historical (Begriffsgeschichte) perspective. This research is driven in part as a response to the way in which the urban is typically treated as a category so self evident that it needs no qualification of its own. While it grows increasingly popular as a topic of study, the urban seems to fade away almost entirely as an object of inquiry itself. At best, it appears as an endless set of data, condemned, for that reason, to remain partial. As a result, we lack a language with which to speak about the urban outside of its factual, demographical and statistical portrayal.

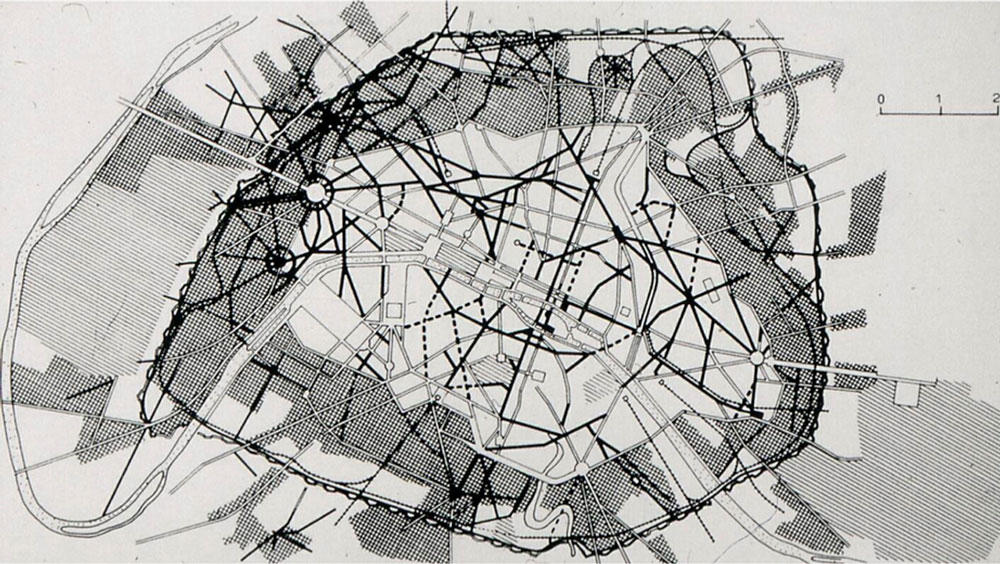

Athens

Fortunately, there have been significant advances toward addressing this; Neil Brenner has for some years been developing his own work around the very same sense of self-evidence that has obfuscated the discursive problem of the urban within the broader fields that intersect in urban studies. What Brenner has shown is that ever since it was first identified as an object of scientific description in early twentieth century, through the work of the Chicago school of urban sociology, the urban has consistently been thought within the same epistemological framework. Ontologies like urban/rural, city/region, centre/periphery and so on were both discovered by this early work and subsequently fixed as the discursive limits within the various academic lines of inquiry that have since branched out from it. From the neo-Marxian work of Soja, Harvey and Davis, to the work of international organisations like the UN HABITAT or the ‘Urban Age’ initiative, all forms of urban studies, he argues, have based their presumptions, discourses and modes of inquiry in one way or another on an epistemological edifice which itself goes unquestioned. The relevance of which today, he compellingly shows, has become increasingly problematic, and that an urbanisation that takes place at a ‘planetary’ scale requires completely new epistemological tools to grasp. Drawing from Lefebvre’s 1970 text, The Urban Revolution, [5] and reading the urban as a arena of neoliberal capitalist expansion, his work is a welcomed call to place the urban at the centre of critical research.

Sao Paulo

What Brenner’s critique makes clear is how the urban (or urbanisation) has hardened itself as a category of empirical, descriptive analysis—a category which can only be made visible through the effects it produces and the facts it assembles. Indeed, much like the weather, urbanisation is something that exists ‘out there’, a condition far too ‘complex’ to present itself as an object to be examined in its own right and thus something which can only be mapped, monitored compared and catalogued. Yet more than this, such a perspective inscribes onto the urban a tenacious burden of the present: Because the urban does not demand that we pose questions to it, our investigations always take place within its spaces and need only to engage whatever ‘new’ condition is happening at any given moment. The urban forces us to see it through its changes, abnormalities and imbalances, foreclosing our analysis of it to remain a kind of perpetual survey of the present. It thus becomes a term used to organise an ever-expanding set of ‘emerging’ problems whose analysis is limited to the particular elements that compose whatever happens to be emerging and the technologies used to register them, leaving the very milieu itself to, once again, remain a neutral background of human existence. At once transhistorical and bound to the immediate present, almost all depictions of the urban treat it as a capacity inherent to the human condition with which we organise ourselves in space. Its status as a quasi-anthropological or sociological category suggests that, by itself, the urban is as close to a ‘natural’ condition as it is to the inevitable fate of humankind—an anthropologically situated category whose ‘complexity’ gives itself over only to the meekest of reformism.

In light of such self-evidence, perhaps the most urgent question to pose is also frighteningly straightforward: What is urbanisation? Cutting across the various presuppositions which underpin urban discourses, can we imagine urbanisation to be a process not at all related to cities? Can there be urbanisation without cities? Can there be cities without urbanisation? Implied in these questions is not only a conceptual and spatial distinction between ‘city’ and ‘urban’, but a suggestion that this distinction itself is one which is historically situated. In other words, it suggests that there was a period of time in which spatial entities called ‘cities’ existed, grew, shrank, were sacked, constructed from scratch and left in ruins, but never urbanised as such; likewise, that there is a time after which cities had been supplanted by an entirely different spatial order which we can call the ‘urban’. If this is true, this distinction is itself a claim about the urban: that the urban has a history. And if this is the case, then it suggests that the urban is also a product of a certain set of historical conditions and decisions: that it has, in other words, a political disposition.

Left: Benevolo L, 1975 The Origins of Modern Town Planning translated by J Landry (MIT Press, Cambridge, MA)

Right: Choay F, 1970 The Modern City: Planning in the 19th Century (G Braziller, New York City)

So what constitutes the urban as both a historically produced and politically conditioned space? How to construct a theory around the urban that is not only a spatial or economic history, but also a political history? For me one clue comes in the oft-repeated historiographical narratives around the birth of ‘the modern city’ or of ‘modern town planning’: circulation.

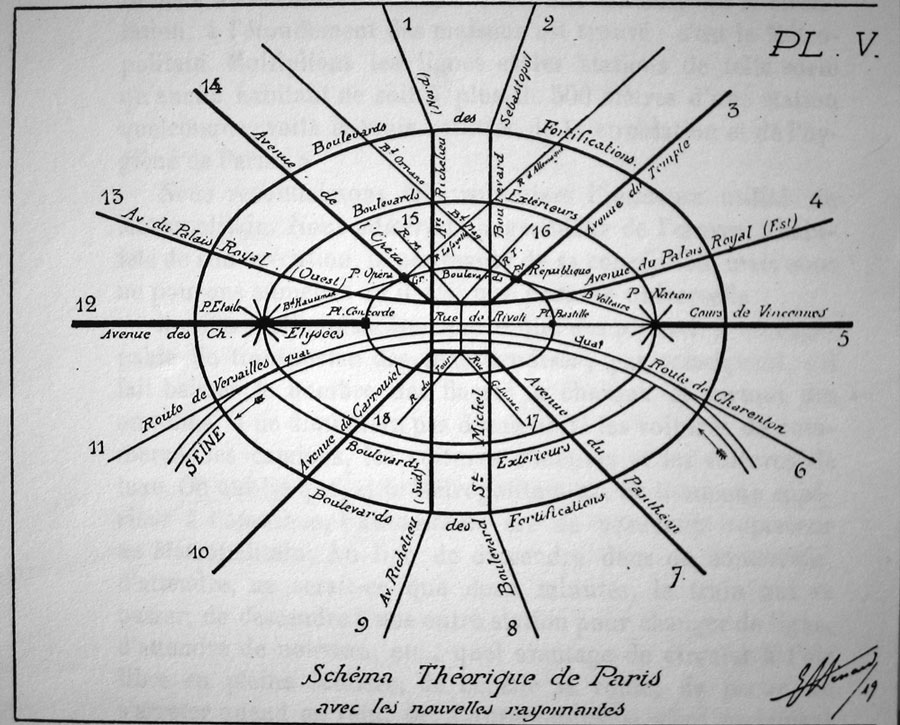

Baron Georges Eugène Haussmann, schematic plan for the reconstruction of Paris showing his trois réseaux (three networks) strategy, 1853.

Baron Georges Eugène Haussmann, schematic plan for the reconstruction of Paris showing his trois réseaux (three networks) strategy, 1853.

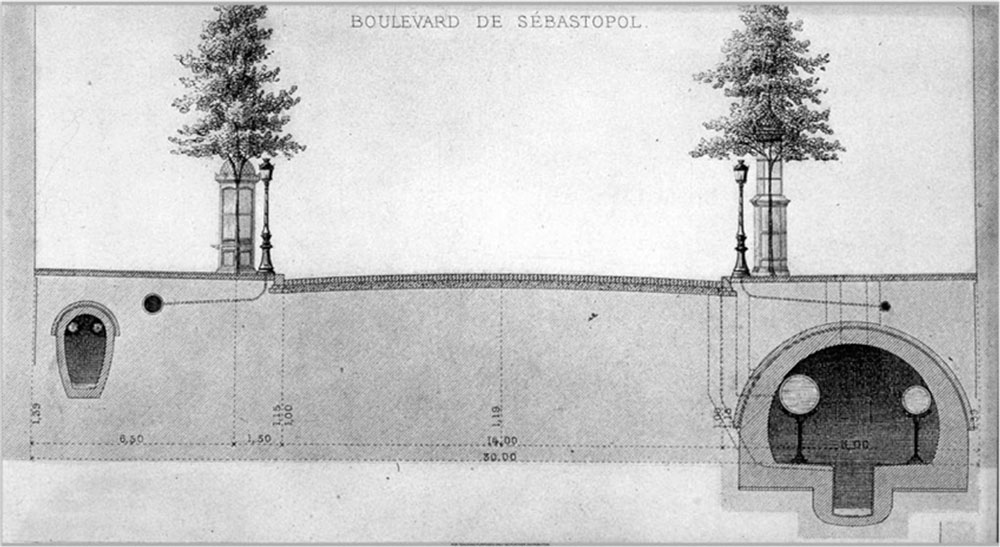

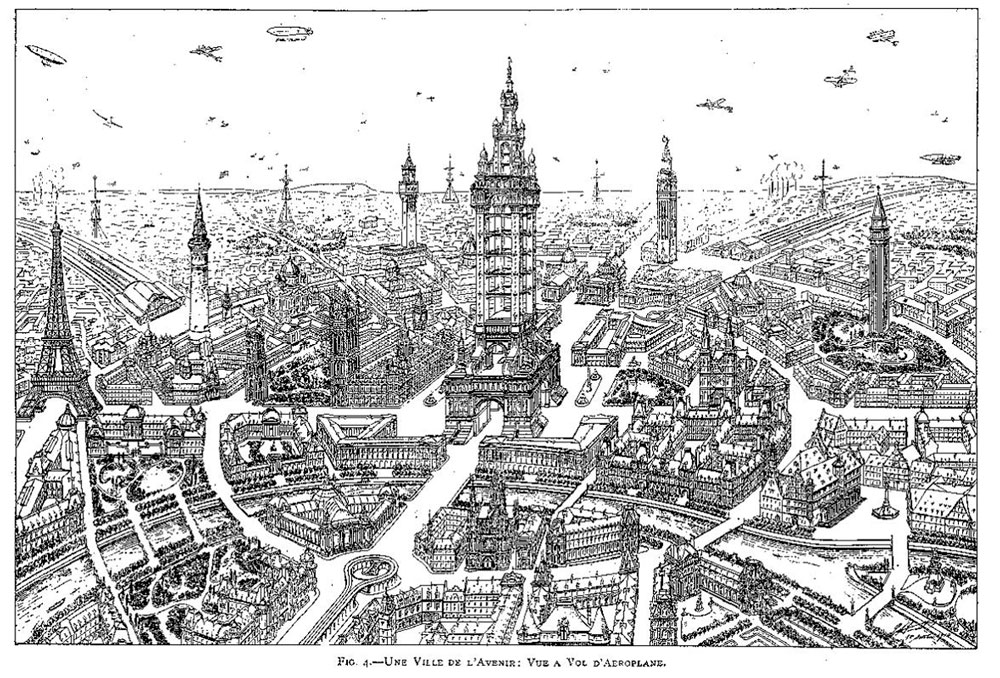

According to this narrative, the ‘modern city’, born in the mid nineteenth century, is one conditioned completely by new technologies of movement, communication, new possibilities of mobility, of the circulation of capital, goods, people, property, resources and services; the circulation of air and water as a direct means to sanitise the city and so on. Idiosyncratic figures like Haussmann stand at the centre of this narrative, offering a new model for reorganising, regularising and renovating the Medieval city into a sleek new space accommodating the ‘modern’ demands of traffic. We are told the foundation of this relationship comes about simply as a result of emergent technologies of circulation, transportation and infrastructure, through the influence of biology and epidemiology as metaphors and technologies for planning the city, and according to the demands of the emergent flows of capital. A narrative, in other words, of a society coming to terms with its ‘innate’ capacities. Indeed, this narrative is more than historical: the relation between circulation and the so-called ‘modern city’ that formed in the nineteenth century has become something of an ideology that has only solidified since then and today stands as an unquestioned truth within practices of urban planning and design.

Baron George Haussmann, section for the reconstruction of Boulevard Sébastopol, Paris, ca. 1850-1870.

While such positivist historicism reduces the painful socio-economic struggles and class warfare of the nineteenth century to a kind of techno-scientifically determined history of the city, it also fails to account for a certain universal zeal around notions of circulation. It leaves unexamined how circulation as a principle of spatial planning had suddenly become so dominant and all-pervasive at this point in time and why circulation seemed to embody a kind of radical idealism shared by figures on both sides of the political spectrum. In fact, what we find when we look below the surface of these various histories is that circulation as a planning principle seemed to promise the opening up of a completely new space in which technologies of movement were equivalent to vehicles of social and economic liberation: Indeed, not only would circulation over the course of the nineteenth century give the European and American city, as it were, its new raison d’être, but it would do so with an overtly political ambition—one that is curiously overlooked by our present histories of the city.

La Ville de l’avenir (The City of the Future), Eugène Hénard, 1910.

Tracing this history, my work is an attempt to construct a kind of ontology of the urban—a political history of this space—which aims to identify the urban as a historically recent spatial order, as a category radically opposed to the ‘city’ and, most importantly, as a political construct. I do this around the notion of circulation. The importance of circulation as an ideological and political device of the nineteenth century becomes clearest in the work of Spanish Engineer Ildefonso Cerdá, and a central text for my research is his Teoría general de la urbanización of 1867, into which my essay for this issue of Society and Space delves in some detail.

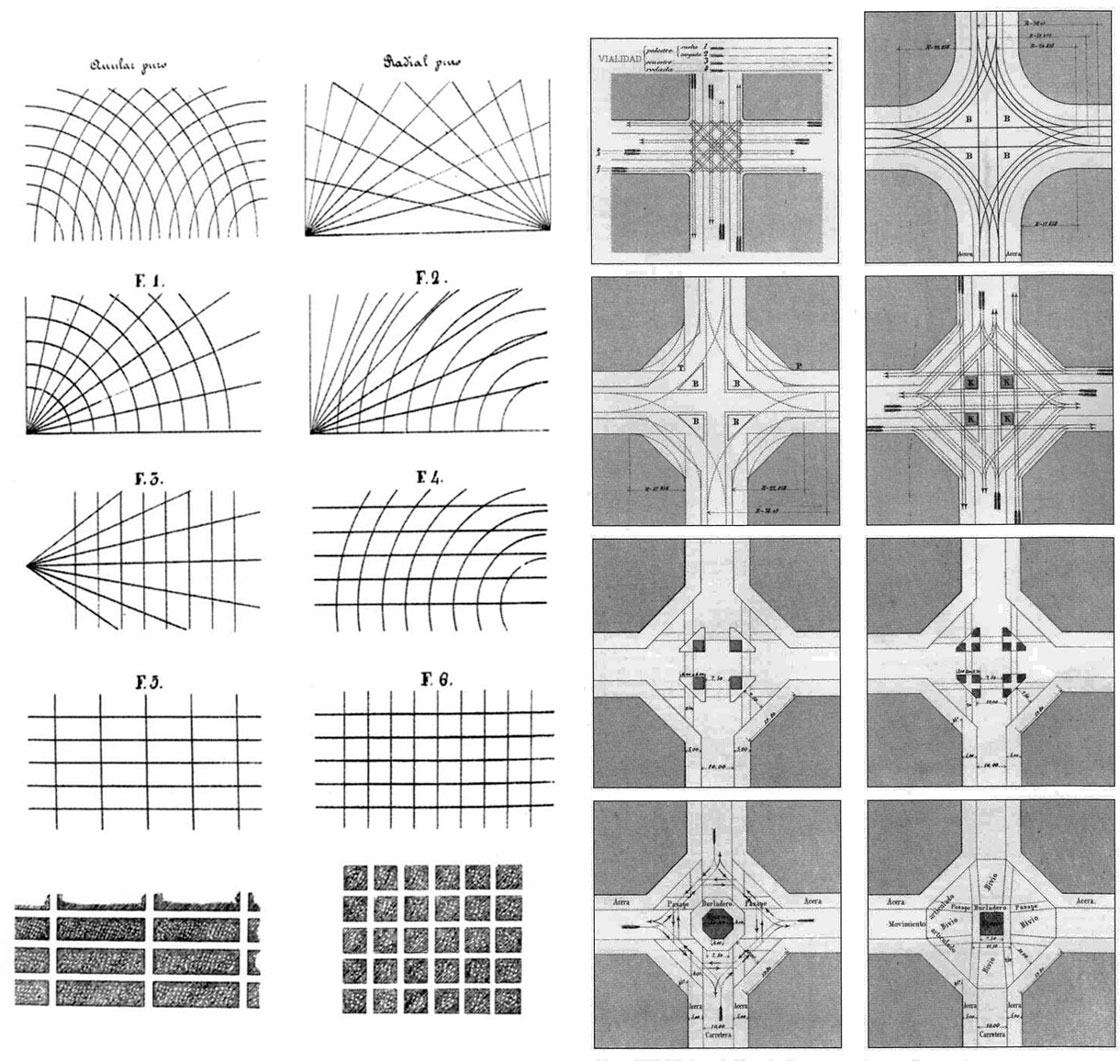

Left: Ildefonso Cerdá, design study of ‘Network of Ways’, a generalisable structuring for the overall layout of the urbe, 1861.

Right: Ildefonso Cerdá, design study of traffic intersections and sidewalk layouts, 1861.

Not only would Cerdá coin the term urbanisation (urbanización) itself but, unlike any of his contemporaries, he would embark on a project to construct an entirely new, universal space of cohabitation aimed to replace the ‘outdated’ notion of ‘city’ altogether. He called this construct the urbe. His entire theory of urbanisation was based on circulation. Every design decision, from the placement of doors and awnings to the layout of the street grid was motivated by and specified according to the demands of circulation. What’s more, urbanisation for Cerdá was an explicitly political project. Because Cerdá saw spatial order as indistinguishable from political form, the idealism behind urbanisation (and thus also circulation) was that it would at once do away with the troublesome, insalubrious city and make redundant the state at the same time.

In this way, the urbe gives us the clearest diagram of this relation and provides a way to historiographically signpost the distinction between city and urban while also allowing us to assess the latter politically. More specifically, by examining Cerdá’s work in context of the emergent liberal nation-state, in the positivist idealism around technology, seen as a means to institutionalise and depoliticise power, the rise of massive municipal administrative apparatuses, the rise of civil society and so forth, we can establish an extensive reading of the urban as the spatial milieu in which the emergent biopolitical horizon could take shape. Cerdá’s work is explicit about this in the way that the space of the urbe, with its infrastructural capture of life in a domestic continuum of circulation and dwelling, supplants any previous, ‘politically overdetermined’ configuration like the ‘city’, ‘town’, ‘burgh’ and so on. This is precisely because the organisation of space, for him, was indistinguishable from the subjugation to politics. The urbe, in replacing the city, also therefore replaces the state. No longer conditioned by an ontology of public/private, the urbe presents a space where the two blur completely into an otherwise homogenous matrix in which new divisions emerge between spaces of production and reproduction, or in Roberto Esposito’s terms, spaces of life’s enhancement and those of its radically immunised protection.

Photograph of the leveling of Gran Via according to Cerdá’s Reform and Extension of Barcelona.

This is one way to approach the urban as both a historically new space and a deeply politicised spatial order whose political disposition resides in its material consistency; a space constituted around a machinic interface between an administrative government and population, which, in less ideal forms, has been incrementally introduced to the modern world from the nineteenth century until the present day. However, rather than taking the nineteenth century’s birth of urbanisation as a historical origin, I turn the analysis, so to speak, on its head: by examining genealogically the broader relation between power and circulation, I attempt to frame the urban as but one historical configuration of power among others whose spatial order became broadly legible and reproducible at a certain point in time. In this way, we get rid of any transhistorical claims or other false essentialisms around the city or the urban. Rather, I start with the more modest question that, if a bond between modern (bio)power and circulation can be located within the urban, can such a coupling be found elsewhere in history (before)? And if so, how and when did the bond form between circulation and political power in the first place? How is it that the city would eventually become the site of this complex? And finally, how did this new spatial formation that resulted, conditioned entirely by circulation, paradoxically make redundant the very notion of city altogether?

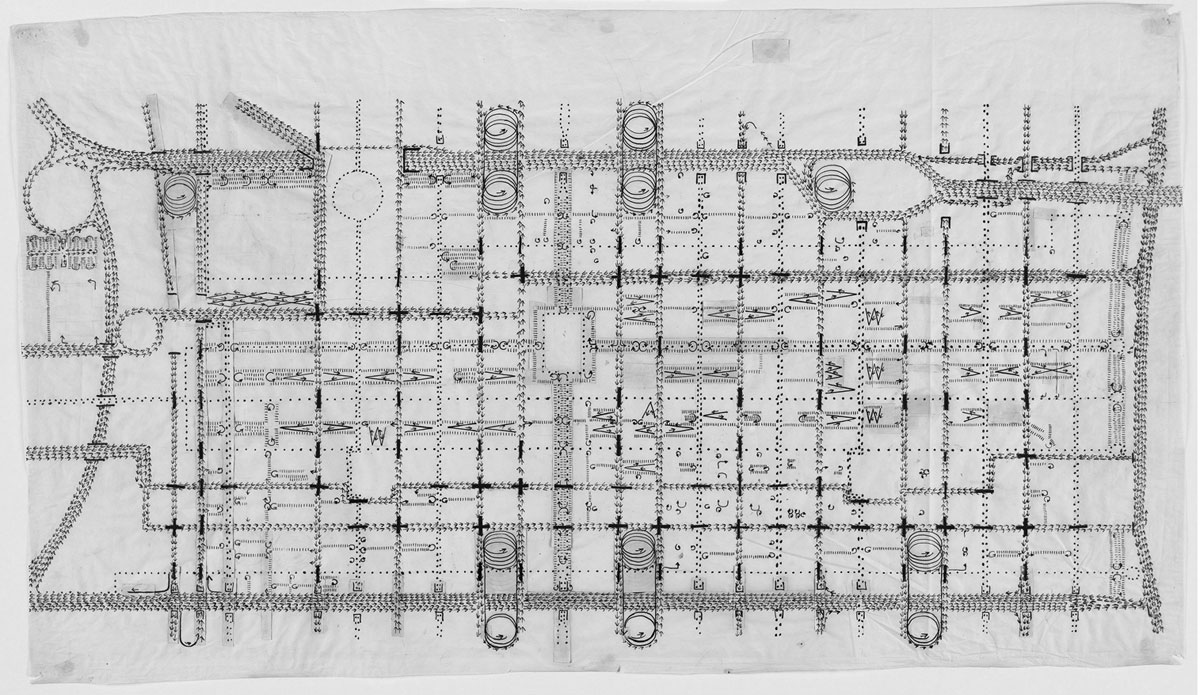

Site plan of Santiago de Leon (today, Caracas) based on the Laws of the Indies, 1578.

By framing the problem of urbanisation in this broader historical relation between spatial order and political form, we are able to locate the history of this category with a certain precision. At the same time, we are able to open up newer and more diverse means by which to access it without the burden of capitalism as the primary analytical frame. Instead, by framing the urban within a political ontology of circulation we can place it alongside an array of related spaces and technologies, from mercantilist networks of trade, to colonial settlements in the so-called New World, to the deeply political geometries of territory.

Knyff and Kip, Plan for the Park at Badminton, 1714.

Knyff and Kip, Plan for the Park at Badminton, 1714.

In fact, by probing this history, and drawing in particular on Stuart Elden’s recent work, what becomes increasingly clear is that the urban as a spatial and an epistemological form was discovered not in the city, as it were, but in the territory: that is to say, the urban is the product of the epistemology of territory being applied to the concrete spaces and administration of the city. In this sense, circulation for Cerdá (as well as for nearly every urbanist since) not only serves as the archetypal principle of design par excellence but also stands as the signature of a territorial spatial order making its entrance for the first time into the space of the city—it is the signature, in other words, of the reorganisation of political power in space. What results is a hybrid spatiality: the urban is both territory and city while being neither at the same time—something in excess of both ontologies. The consequences of this not only gives us a new understanding of the urban as a space radically opposed to the city, but it also has potential implications for how we can develop contemporary understandings of territory itself.

Theoretical Scheme of Paris Eugène Hénard, 1919.

Theoretical Scheme of Paris Eugène Hénard, 1919.

At once territorial and domestic, the urban, was from the start conceived by Cerdá as a totality. Its historical task, for him, was to expand endlessly in all directions, breaking all previous spatio-political boundaries and uniting the world in a single, contiguous urban settlement unifying humanity in a peaceful cosmopolitanism. Perhaps the difference today between Cerdá’s idealised vision of urbanisation and ‘actually-existing’ urbanisation is that the latter persists without an idealism, as a kind of self-replicating, self-evident machine; means without ends. Nevertheless, the condition today, approaching what Neil Brenner and Christian Schmid have called ‘Planetary Urbanisation’, is strikingly reminiscent of what Cerdá prophesied nearly 150 years ago. Brenner’s work is clearly important in addressing the problem of the urban itself as an urgently under theorised category, yet his reading of the urban, based heavily on Lefebvre’s text, depicts it as a world-encompassing organisation of space ordered principally by the dictates of capital. While this is surely an accurate reading and provides much-needed insight into the urban, it also limits itself to seeing the urban as the planetary material correlate of the increasingly immaterial consistency of global capitalism—a kind of extrusion of capitalism in concrete infrastructures and built form, rambling across vast landscapes, oceans and atmosphere of the earth. [6] The work carried out in his Urban Theory Lab, creating wonderfully articulate GIS maps and satellite imagery to capture the vastness of the urban (classified as both ‘concentrated urbanisation’ and ‘extended urbanisation’ [7]), simultaneously fails to express much more about it as a historically and politically produced space.

Plan for the Reform and Extension of Barcelona, Ildefonso Cerdá, 1859.

Ironically, as critical as he is of the way in which the urban is described today through programs like LSE’s ‘Urban Age’, etc., Brenner’s own work fails to escape some of the same fundamental problems that this work reproduces, representing the urban through the spectacle of its immense formlessness. One might suggest that his work tends to hang too much of its critical analysis on Lefebvre’s (and indeed Marx’s) existing analyses of capitalism, leaving the urban to stand in as a spatial and material signifier of another totality: capitalism itself. Like so many before him, urbanisation—the vehicle of rampant fixing of surplus capital, the arena in which creative destruction of the material world takes place in the name of neoliberal strategies of capital accumulation and so on—still remains a politically neutral category in itself. As well, perhaps because of relying on Lefebvre’s thesis as he does or perhaps by concentrating on that which is ‘emerging’, very little investigation goes in to the historical production of this category of space, and almost no effort is made to interrogate the relationship that this spatial order orchestrates with new political forms and the ordering of forms of life.

Traffic Studies (Philadelphia), Louis Kahn, 1952.

Lefebvre’s The Urban Revolution, while important in making the bold attempt to distinguish between city and urban, and thus giving birth to many of the important developments we’ve seen in recent years, simply does not go far enough in the direction it embarks upon. By placing too much reliance on a fairly imprecise and overly simplified causality, linking all too confidently the rise of an urban society to that of capitalism, it paradoxically leaves the urban itself unscrutinised. And while the ‘virtual urbanisation’ of the entire planet may have seemed to have taken hold in 1970 [8], such a claim framed in this way does little more than to dramatise the problem for which the urban, for Lefebvre, stands: global capitalism. While certainly a link between the two can be traced in Cerdá and many other urbanists’ unbridled embrace of nineteenth century capitalism, his theory of urbanisation went far beyond this, setting in place the outlines of an entirely new apparatus in which power, authority and control circulated throughout the extensive reach of infrastructure itself, in turn transforming domesticity into an object of governmental calculation and the site of its permanent intervention. For Cerdá, these were the administrative consequences—a social contract of sorts—needed to achieve a universal society residing in a single urbe that would stretch across the entire planet, spanning both land and sea. Indeed, the idealism he invested in the urbe was that it was both city and territory while being neither at the same time; a spatial order designed to expand, to urbanise. This sentiment is perhaps best captured in a triumphant injunction printed on the frontispiece of the Teoría: “Ruralise the urban, urbanise the rural: fill the earth”. [9]

This is not simply a matter of being historically rigorous as a point of scholarly practice. Rather it is a concern for how we evaluate the present itself. The problem with an under examined history of a category like the urban is that it forecloses us to read all contemporary expressions of it as merely more of the same—the accumulated materialisation of another force at work. What I would like to show is that, while certainly interrelated, urbanisation and capitalism operate more in parallel with one another, without a clear hierarchy. By understanding this, we can begin to examine the political consistency of space that the urban sustains and reproduces, binding life to forms of control and power (of which capital is certainly one). More than being burdened by the present—waiting for the totality of the urban to finally make itself visible—our work can instead free the present to become a moment of radical invention, a moment of imagination, where the horizon that the urban seems to occupy can begin to recede and new spaces can appear in its place. For as with all totalities, what sustains them is our conviction that that is in fact what they are.

![‘City Plus’, OMA, concept image for Rebuild by Design initiative. In their own words, ‘[t]his means further densification and defense of high value, high impact, high potential sites—cities’, 2013. 01_oma-rebuild-by-design-1](https://urbannext.net/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/01_oma-rebuild-by-design-1.jpg)